Presidency hinges on tight races in battleground states

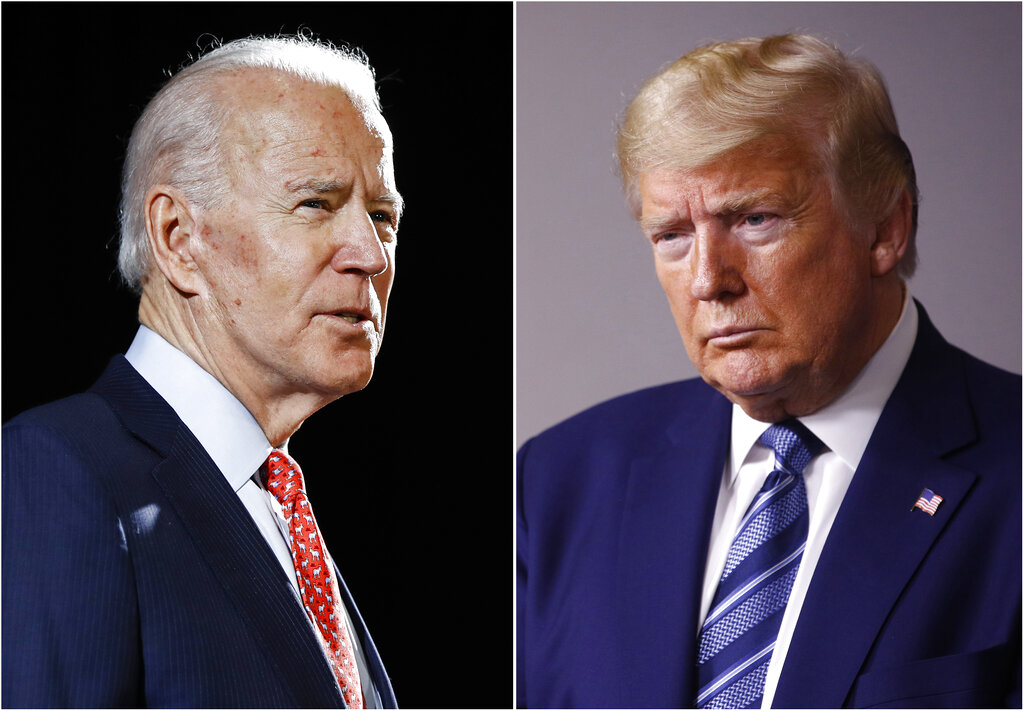

The fate of the United States presidency hung in the balance Wednesday morning, as President Donald Trump and Democratic challenger Joe Biden battled for three familiar battleground states — Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania — that could prove crucial in determining who wins the White House. It was unclear when or how quickly a winner could be determined. A late burst of votes in Michigan and Wisconsin gave Biden a small lead in those states, but it was still too early to call the race. Hundreds of thousands of votes were also outstanding in Pennsylvania. The high stakes election was held against the backdrop of a historic pandemic that has killed more than 230,000 Americans and wiped away millions of jobs. Both candidates spent months pressing dramatically different visions for the nation’s future and voters responded in huge numbers, with more than 100 million people casting votes ahead of Election Day. But the margins were exceedingly tight, with the candidates trading wins in battleground states across the country. Trump picked up Florida, the largest of the swing states, while Biden flipped Arizona, a state that has reliably voted Republican in recent elections. Neither cleared the 270 Electoral College votes needed to carry the White House. Trump, in an extraordinary move from the White House, issued premature claims of victory and said he would take the election to the Supreme Court to stop the counting. It was unclear exactly what legal action he might try to pursue. Biden, briefly appearing in front of supporters in Delaware, urged patience, saying the election “ain’t over until every vote is counted, every ballot is counted.” “It’s not my place or Donald Trump’s place to declare who’s won this election,” Biden said. “That’s the decision of the American people.” Vote tabulations routinely continue beyond Election Day, and states largely set the rules for when the count has to end. In presidential elections, a key point is the date in December when presidential electors met. That’s set by federal law. Several states allow mailed-in votes to be accepted after Election Day, as long as they were postmarked by Tuesday. That includes Pennsylvania, where ballots postmarked by Nov. 3 can be accepted if they arrive up to three days after the election. Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf tweeted that his state had over 1 million ballots to be counted and that he “promised Pennsylvanians that we would count every vote and that’s what we’re going to do.” Trump appeared to suggest those ballots should not be counted, and that he would fight for that outcome at the high court. But legal experts were dubious of Trump’s declaration. “I do not see a way that he could go directly to the Supreme Court to stop the counting of votes. There could be fights in specific states, and some of those could end up at the Supreme Court. But this is not the way things work,” said Rick Hasen, a professor of law and political science at the University of California-Irvine. Trump has appointed three of the high court’s nine justices including, most recently, Amy Coney Barrett. Democrats typically outperform Republicans in mail voting, while the GOP looks to make up ground in Election Day turnout. That means the early margins between the candidates could be influenced by which type of votes — early or Election Day — were being reported by the states. Throughout the campaign, Trump cast doubt about the integrity of the election and repeatedly suggested that mail-in ballots should not be counted. Both campaigns had teams of lawyers at the ready to move into battleground states if there were legal challenges. The tight overall contest reflected a deeply polarized nation struggling to respond to the worst health crisis in more than a century, with millions of lost jobs, and a reckoning on racial injustice. Trump kept several states, including Texas, Iowa and Ohio, where Biden had made a strong play in the final stages of the campaign. But Biden also picked off states where Trump sought to compete, including New Hampshire and Minnesota. But Florida was the biggest, fiercely contested battleground on the map, with both campaigns battling over the 29 Electoral College votes that went to Trump. The president adopted Florida as his new home state, wooed its Latino community, particularly Cuban-Americans, and held rallies there incessantly. For his part, Biden deployed his top surrogate — President Barack Obama — there twice in the campaign’s closing days and benefitted from a $100 million pledge in the state from Michael Bloomberg. Democrats entered the night confident not only in Biden’s prospects, but also in the the party’s ability to take control of the Senate. But the GOP held several seats that were considered vulnerable, including in Iowa, Texas and Kansas. The House was expected to remain under Democratic control. The coronavirus pandemic — and Trump’s handling of it — was the inescapable focus for 2020. For Trump, the election stood as a judgment on his four years in office, a term in which he bent Washington to his will, challenged faith in its institutions and changed how America was viewed across the globe. Rarely trying to unite a country divided along lines of race and class, he has often acted as an insurgent against the government he led while undermining the nation’s scientists, bureaucracy and media. The momentum from early voting carried into Election Day, as an energized electorate produced long lines at polling sites throughout the country. Turnout was higher than in 2016 in numerous counties, including all of Florida, nearly every county in North Carolina and more than 100 counties in both Georgia and Texas. That tally seemed sure to increase as more counties reported their turnout figures. Voters braved worries of the coronavirus, threats of polling place intimidation and expectations of long lines caused by changes to voting systems, but appeared undeterred as turnout appeared it would easily surpass the 139 million ballots cast four years ago. No major problems arose on Tuesday, outside the typical glitches

Donald Trump raises $210 million, robust but well short of Joe Biden

Trump’s campaign released its figure Wednesday, several days later than usual and nearly a week after the Biden campaign unveiled its total, the highest for any one month during a presidential campaign.

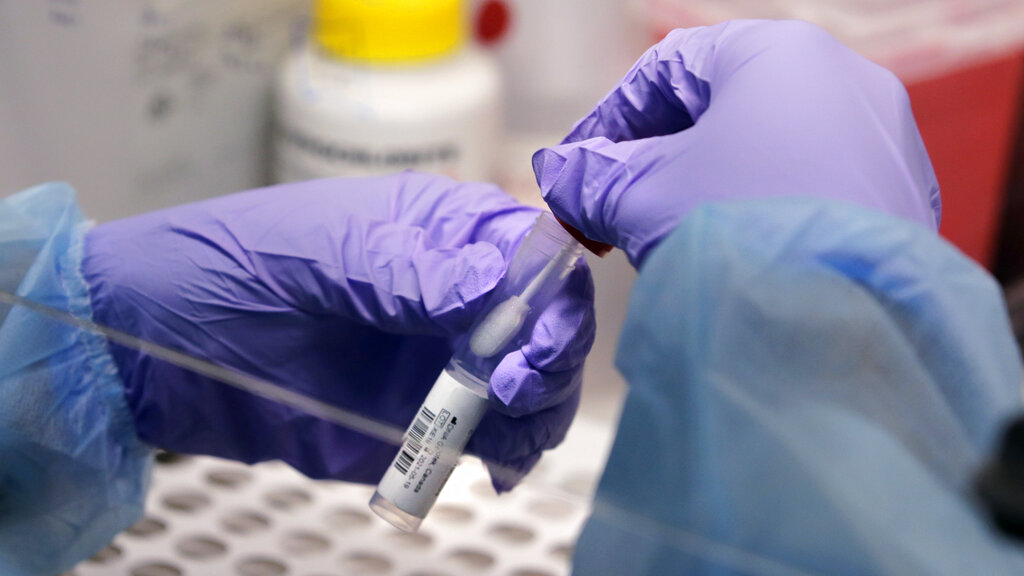

US officials: Russia behind spread of virus disinformation

Russian intelligence services are using a trio of English-language websites to spread disinformation about the coronavirus pandemic, seeking to exploit a crisis that America is struggling to contain ahead of the presidential election in November, U.S. officials said Tuesday. Two Russians who have held senior roles in Moscow’s military intelligence service known as the GRU have been identified as responsible for a disinformation effort meant to reach American and Western audiences, U.S. government officials said. They spoke to The Associated Press on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly. The information had previously been classified, but officials said it had been downgraded so they could more freely discuss it. Officials said they were doing so now to sound the alarm about the particular websites and to expose what they say is a clear link between the sites and Russian intelligence. Between late May and early July, one of the officials said, the websites singled out Tuesday published about 150 articles about the pandemic response, including coverage aimed either at propping up Russia or denigrating the U.S. Among the headlines that caught the attention of U.S. officials were “Russia’s Counter COVID-19 Aid to America Advances Case for Détente,” which suggested that Russia had given urgent and substantial aid to the U.S. to fight the pandemic, and “Beijing Believes COVID-19 is a Biological Weapon,” which amplified statements by the Chinese. The disclosure comes as the spread of disinformation, including by Russia, is an urgent concern heading into November’s presidential election as U.S. officials look to avoid a repeat of the 2016 contest, when a Russian troll farm launched a covert social media campaign to divide American public opinion and to favor then-candidate Donald Trump over Democratic opponent Hillary Clinton. The U.S. government’s chief counterintelligence executive warned in a rare public statement Friday about Russia’s continued use of internet trolls to advance their goals. Even apart from politics, the twin crises buffeting the country and much of the world — the pandemic and race relations and protests — have offered fertile territory for misinformation or outfight falsehoods. Trump himself has come under scrutiny for sharing misinformation about a disproven drug for treating the coronavirus in videos that were taken down by Twitter and Facebook. Officials described the Russian disinformation as part of an ongoing and persistent effort to advance false narratives and cause confusion. They did not say whether the effort behind these particular websites was directly related to the November election, though some of the coverage appeared to denigrate Trump’s Democratic challenger, Joe Biden, and called to mind Russian efforts in 2016 to exacerbate race relations in America and drive corruption allegations against U.S. political figures. Though U.S. officials have warned before about the spread of disinformation tied to the pandemic, they went further on Tuesday by singling out a particular information agency that is registered in Russia, InfoRos, and that operates a series of websites — InfoRos.ru, Infobrics.org, and OneWorld.press — that have leveraged the pandemic to promote anti-Western objectives and to spread disinformation. Officials say the sites promote their narratives in a sophisticated but insidious effort that they liken to money laundering, where stories in well-written English — and often with pro-Russian sentiment — are cycled through other news sources to conceal their origin and enhance the legitimacy of the information. The sites also amplify stories that originate elsewhere, the government officials said. An email to InfoRos was not immediately returned Tuesday. Beyond the coronavirus, there’s also a focus on U.S. news, global politics, and topical stories of the moment. A headline Tuesday on InfoRos.ru about the unrest roiling American cities read “Chaos in the Blue Cities,” accompanying a story that lamented how New Yorkers who grew up under the tough-on-crime approach of former Mayors Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg “and have zero street smarts” must now “adapt to life in high-crime urban areas.” Another story carried the headline of “Ukrainian Trap for Biden,” and claimed that “Ukrainegate” — a reference to stories surrounding Biden’s son Hunter’s former ties to a Ukraine gas company — “keeps unfolding with renewed vigor.” U.S. officials have identified two of the people believed to be behind the sites’ operations. The men, Denis Valeryevich Tyurin and Aleksandr Gennadyevich Starunskiy, have previously held leadership roles at InfoRos but have also served in a GRU unit specializing in military psychological intelligence and maintain deep contacts there, the officials said. InfoRos and One World’s ties to the Russian state have attracted scrutiny in the past from European disinformation analysts. In 2019, a European Union task force that studies disinformation campaigns identified One World as “a new addition to the pantheon of Moscow-based disinformation outlets.” The task force noted that One World’s content often parrots the Russian state agenda on issues including the war in Syria. A report published last month by a second, nongovernmental organization, Brussels-based EU DisinfoLab, examined links between InfoRos and One World to Russian military intelligence. The researchers identified technical clues tying their websites to Russia and identified some financial connections between InfoRos and the government. “InfoRos is evolving in a shady grey zone, where regular information activities are mixed with more controversial actions that could be quite possibly linked to the Russian state’s information operations,” the report’s authors concluded. On its English-language Facebook page, InfoRos describes itself as an “Information agency: world through the eyes of Russia.” Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

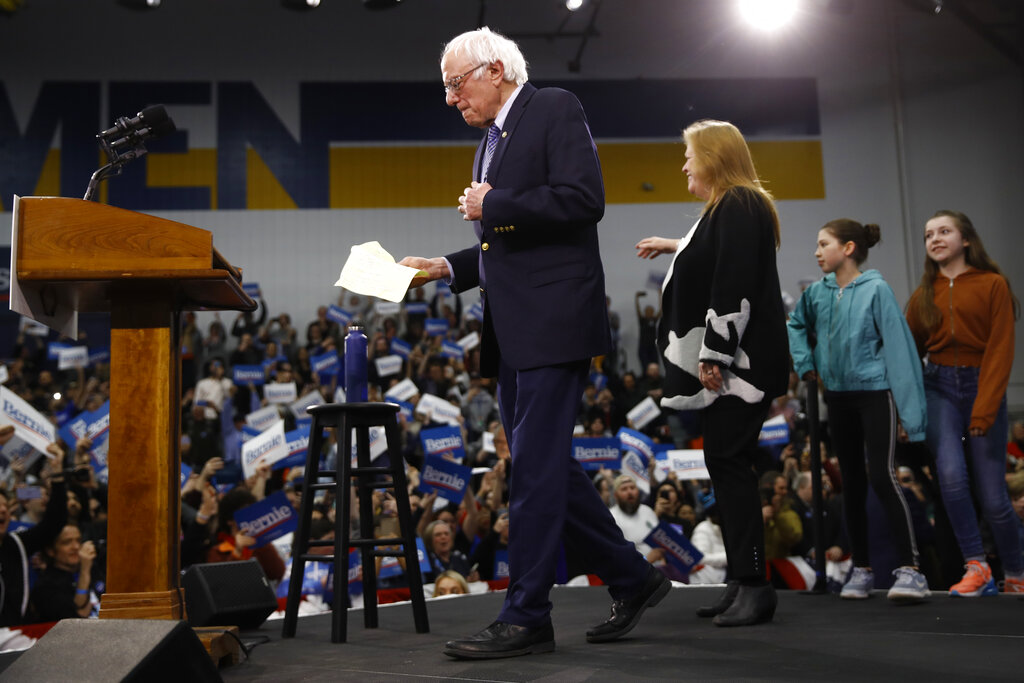

Some Democrats fear fallout from Bernie Sanders atop the ticket

Democrats are worried that Sanders’ socialist label and unyielding embrace of controversial proposals such as medicare for all will repel voters.

How crucial is New Hampshire win? It depends on whom you ask

Democrats are attempting a variety of strategies as New Hampshire is set to vote.

Joe Biden’s poor showing in Iowa shakes establishment support

Some establishment Democrats are questioning whether Biden can reclaim front-runner status.

Iowa a carnival of democracy for media — until it went sour

Unlike in past election cycles, Iowa seemed to sneak up on television viewers, despite nearly a year’s worth of debates and campaigning.

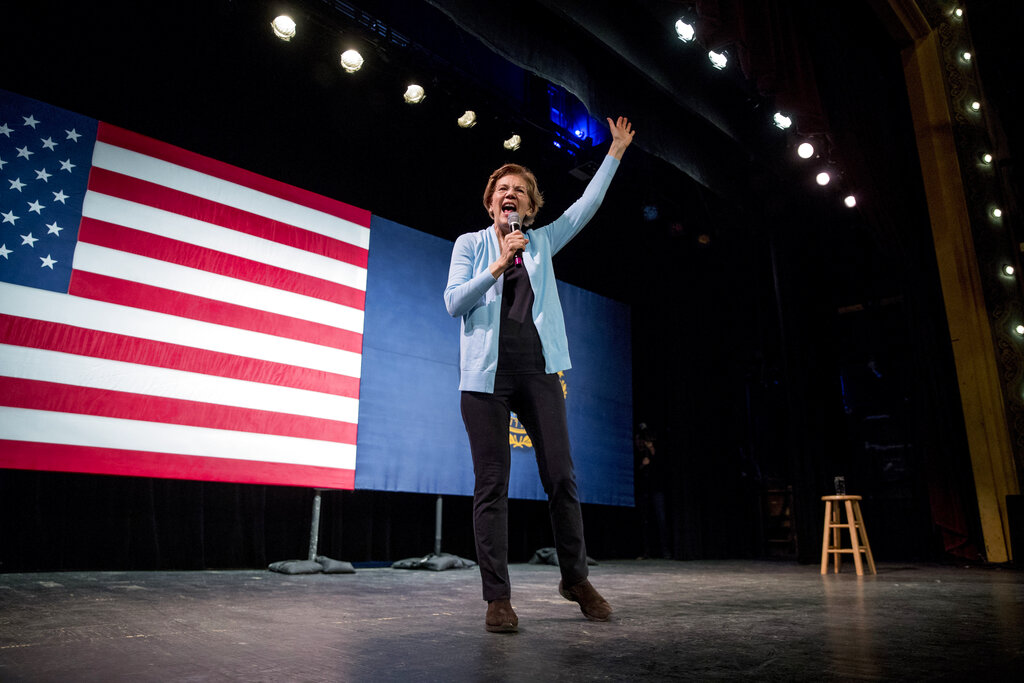

Campaign crunch time forces progressives to eye private jets

Private planes present unique issues for Warren and Sanders.

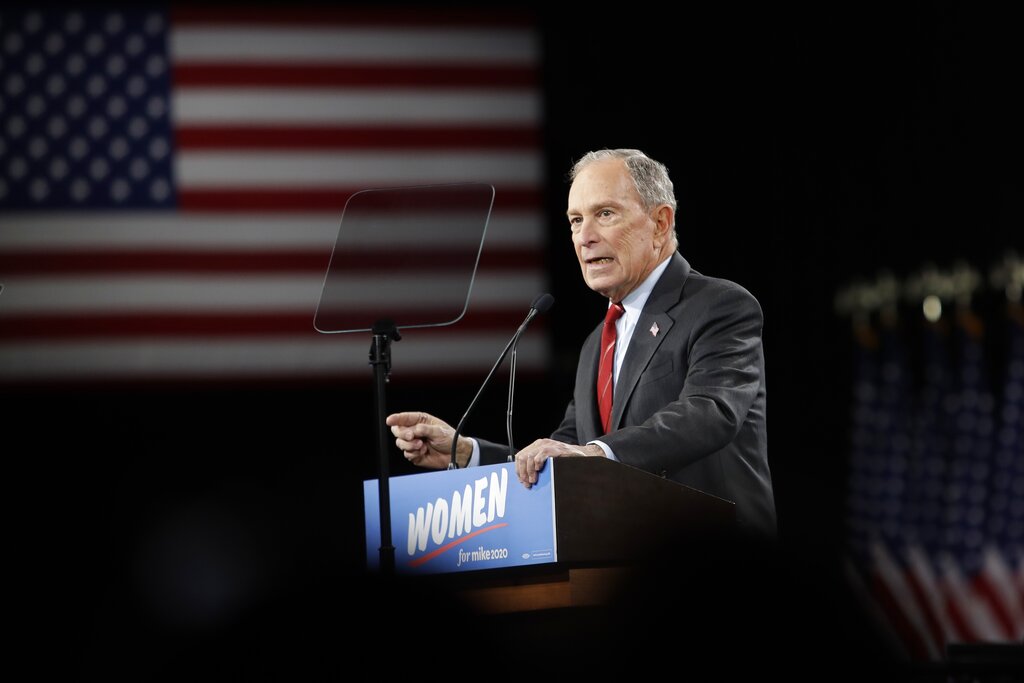

Michael Bloomberg outlines plans for cleaner buildings, cars

Bloomberg’s plan outlines how he would cut down pollution from cars and trucks.

Amid Iran and impeachment, Donald Trump’s focus is reelection

Donald Trump is being attacked on two sides.

Inside the Statehouse: What Does the Presidential Race Look Like Nationally?

Alabama’s leading columnist discusses Alabama’s place in the US Presidential election.

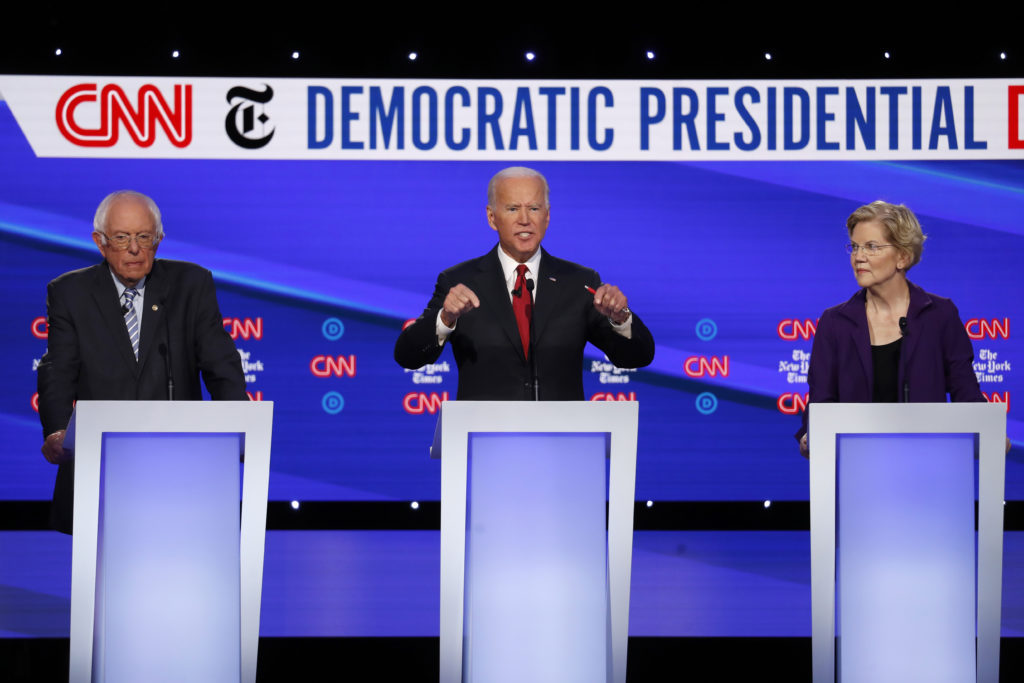

2020 Watch: Messy primary finally meets election year

The presidential politics calendar turned to 2020 nearly a year ago. This week, the actual date catches up. What we’re watching as the preseason closes and election year opens: Days to Iowa caucuses: 35 Days to general election: 309 THE NARRATIVE The ups, downs and swerves of 2019 yielded a stable top slate. Former Vice President Joe Biden leads most national polls of Democratic primary voters, with Sens. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts within striking distance. Yet in the first caucus state of Iowa and the first primary state of New Hampshire, there’s a jumble of Biden, Sanders, Warren and Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Indiana. At first glance, it’s a clean choice: Biden and Buttigieg hail from the center-left; Warren and Sanders come from the progressive left. Reality is more layered. All four have weaknesses within Democrats’ diverse electorate; each makes a different case for carrying the banner against President Donald Trump, who is now impeached but a near certainty to survive a Senate trial. If that’s not enough indecision, several wildcards — including two billionaires — still hope to scramble the contest. THE BIG QUESTIONS Money: Who can (sort of) compete with Michael Bloomberg’s wallet? The fourth-quarter fundraising period ends Tuesday. Warren and Sanders set the early curve for grassroots donations, outpacing Buttigieg and Biden, who tap traditional deep-pocketed contributors in addition to online donors. Now those small-donor juggernauts must compete with former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who’s used a share of his estimated $50 billion personal fortune to blanket television and digital advertising and build an expansive staff in Super Tuesday states. For his rivals, it’s not so much about keeping up; Bloomberg can easily outspend every other campaign, including that of fellow billionaire Tom Steyer. But there’s only so much television time for sale, and if Warren and Sanders want to plow big money into Super Tuesday, especially the expensive television markets of California, they’ll need as much cash as possible ahead of time. Biden, meanwhile, has already secured his best fundraising quarter (a relative comparison for a candidate who’s lagged other top-tier contenders). The question is whether Biden’s “best” mollifies establishment Democrats who waved red flags when he reported having less than $9 million on hand at September’s end. Money, Part II: How long can Cory Booker keep going? The year-end deadline is critical for New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker as he reaches for relevance. The last of two African American candidates (along with former Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick), Booker made a do-or-die money appeal in September, and it worked. But it’ll take more than scraping by to fund the turnaround he envisions: a surprise finish in overwhelmingly white Iowa to kick-start a dramatic rise in more diverse primary states that follow (Barack Obama’s 2008 path). Campaigns that hit big fundraising numbers tend to leak that news before Federal Election Commission filings are due. Candidates with bad news tend to wait. So, it bears watching how Booker’s team plays it to start January. Is Amy Klobuchar being overlooked in Iowa? Those previously mentioned Iowa and New Hampshire jumbles omit Amy Klobuchar. But the Minnesota senator is plugging away in both states. She just hit her 99th Iowa county (that’s all of them), demonstrating her effort to use complex caucus rules that can reward candidates with a wide geographic footprint. Notably, Klobuchar’s strategy tracks Biden. Both aim for a more consistent appeal across 1,679 precincts than Warren, Sanders and Buttigieg muster on Feb. 3. The question becomes how many precincts give both Biden and Klobuchar the minimum 15 percent support required to count toward delegates. Anyone who doesn’t hit that viability mark drops from subsequent ballots, their backers going up for grabs. Biden’s Iowa hopes depend in part on picking up moderates on realignment votes (read: Klobuchar and Buttigieg supporters). If Klobuchar is as strong as she hopes to be, she could turn that strategy around on Biden, driving him below viability and attracting his supporters on later ballots. Biden returns to Iowa this week for another bus tour, though not as lengthy as his eight-day jaunt after Thanksgiving. Is Sanders a true contender this time? Sanders lost the 2016 nomination because of Hillary Clinton’s advantage among non-white Democrats. Since then, Sanders has deepened his ties among Latinos, African Americans and other non-whites. Warren and Buttigieg are still chasing that success. Sanders’ advisers believe the senator is well-positioned to challenge Biden among non-whites if he’s able to build early momentum in New Hampshire and Iowa, where Sanders will spend New Year’s Eve. If they’re right, that would open avenues to delegates Sanders didn’t get in 2016. Is Trump’s position improving? The president has never been popular judged in a vacuum. In 2016, he won GOP primaries with pluralities and lost the general election popular vote. As president, he’s never reached majority job approval in Gallup’s polling. But he’s still hovering in the 40s, not far from where his immediate predecessors were 11 months before winning second terms. Impeachment proceedings haven’t affected Trump’s standing. Meanwhile, the same Democratic-run House that impeached him approved his new North America trade pact. Top-line economic numbers shine, even if the on-ground reality is uneven. And Trump could be on the cusp of a peace deal in Afghanistan after the Taliban ruling council on Sunday agreed to a temporary cease-fire. As frenetic as Trump’s messaging is, he proved in 2016 that he relishes framing binary choices for voters, and he’s more than convinced he has a case in 2020. THE FINAL THOUGHT Most voters are just tuning into a presidential race that’s raged for a year. They’ll find a Democratic contest featuring stark options on policy and personality, but lacking an undisputed favorite. Candidates are navigating primary politics: dancing along the progressive-liberal-moderate spectrum and carefully choosing when to go after each other. At the same time, Trump dominates the 2020 narrative, a fact demonstrated most recently as Biden spent two days talking about whether he’d testify in a Senate trial on Trump’s removal from office.