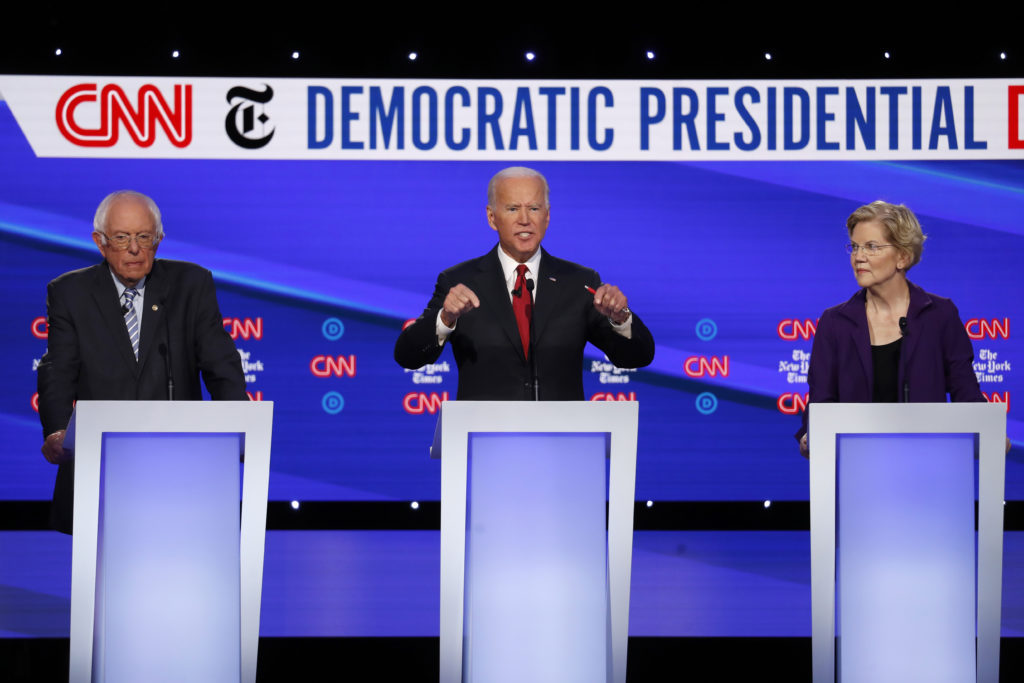

Takeaways from the democratic presidential debate

Democratic presidential candidates offered two very different debates during their final forum of 2019. In the first half, they spent much of their time making the case for their electability in a contest with President Donald Trump. The second half was filled with friction over money in politics, Afghanistan and experience. MONEY TALKED The candidates jousted cordially over the economy, climate change and foreign policy. But it was a wine cave that opened up the fault lines in the 2020 field. That wine cave, highlighted in a recent Associated Press story, is where Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Indiana, recently held a big-dollar Napa Valley fundraiser, and Sen. Elizabeth Warren — who along with Sen. Bernie Sanders has eschewed fundraisers in favor of small-dollar grassroots donations — slammed him for it. “Billionaires in wine caves should not pick the next president of the United States,” Warren said. Buttigieg struck back, noting that he was the only person on the stage who was not a millionaire or billionaire. He said that if Warren donated to him he’d happily accept it even though she’s worth “ten times” what he is. He also added that Warren had only recently sworn off big money donations. “These purity tests shrink the stakes of the most important election,” Buttigieg snapped. It was an unusually sharp exchange between Warren and Buttigieg. The two have been sparring as Warren’s polling rise has stalled out and Buttigieg poached some of her support among college-educated whites. And Warren was not the only one going after Buttigieg. Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota hit him on another front, namely what she said was his lack of experience compared to her Senatorial colleagues on stage. Still, the divide is about more than Warren and Buttigieg. It’s about the direction of the party — whether it should become staunchly populist, anti-corporate and solely small-dollar funded, or rely on traditional donors, experience and ideology. IMPEACHMENT AS PROXY The first question in the debate was about impeachment. But the answer from the Democratic candidates was about electability. Most candidates had no answer to their party’s biggest challenge — getting Trump’s voters to abandon him over his conduct. Warren talked about one of her favorite themes, “corruption” in Washington. Sanders talked about having to convince voters Trump lied to them about helping the working class. Klobuchar, a former prosecutor, laid out the case against Trump as if she were giving the opening statement in his Senate trial. Buttigieg said the party can’t “give into that sense of hopelessness” that the GOP-controlled Senate will simply acquit Trump because Republican voters aren’t convinced. But Buttigieg didn’t provide any other hope. Only businessman Andrew Yang gave an explanation for why impeachment hasn’t changed minds. “We have to stop being obsessed about impeachment, which strikes many Americans like a ball game where you know what the score will be.” Instead, Yang said, the party has to grapple with the issues that got Trump elected — the loss of good jobs. BIDEN STEADY Former Vice President Joe Biden has held steady throughout the Democratic race as one of the top two or three candidates by almost any measure. He has done that with debate performances described as flat, uneven, and uninspired. He had a better night Thursday, even on a question about of one of his views that causes fellow Democrats to groan: that he can work with Republicans once he beats Trump in November. “If anyone has reason to be angry with the Republicans and not want to cooperate it’s me, the way they’ve attacked me, my son, my family,” Biden said, a reference to Trump’s push to investigate his son Hunter that led to the president’s impeachment. “I have no love. But the fact is we have to be able to get things done and when we can’t convince them, we go out and beat them.” Unlike others on the stage, he said pointedly that he doesn’t believe it’ll be impossible to ever work together with the other party. “If that’s the case,” Biden said, “we’re dead as a country.” He came close to trouble by initially saying he would not commit to a running for a second term, them quickly said that would be presumptuous to presume a first one. AMERICAN ROLE IN THE WORLD Is the greatest danger to America’s foreign interests and alliances coming from within the White House? Democratic presidential candidates faulted Trump on multiple fronts for his failure to lead in key disputes and areas of international friction, including in the Middle East and China. Buttigieg said Trump was “echoing the vocabulary” of dictators in his relentless attacks on the free press. Klobuchar said the president had “stood with dictators over innocents.” And Tom Steyer warned against isolating the U.S. from China, saying the two nations needed to work together on climate change. On Israel, Biden argued that Trump had played to fears and prejudices and stressed that a two-state solution was needed for peace to ever be achieved. The former vice president said Washington must rebuild alliances “which Trump has demolished.’” With China, “We have to be firm. We don’t have to go to war,” Biden said. “We have to be clear, “This is as far as you go, China,” he added. YANG’S PRO MOVES In June, Yang was a political punchline. During the first few Democratic debates, the entrepreneur, who has never before run for office, looked lost onstage, struggling to be heard over the din of nine other candidates. But on Thursday night, Yang looked like a pro. When the candidates debated complex foreign policy, Yang talked about his family in Hong Kong, the horror of China’s crackdown there and how to pressure them to respect human rights. When some candidates equivocated over whether nuclear energy should be used to combat climate change, Yang had the last word when he said: “We need to have everything on the table in a crisis situation.” And when a moderator noted that Yang was

Kamala Harris ends campaign for presidential bid, citing lack of funding

Sen. Kamala Harris told supporters on Tuesday that she was ending her bid for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination, an abrupt close to a candidacy that held historic potential. “I’ve taken stock and looked at this from every angle, and over the last few days have come to one of the hardest decisions of my life,” the California Democrat said. “My campaign for president simply doesn’t have the financial resources we need to continue.” A senior campaign aide said Harris made the decision Monday after discussing the path forward with family and other top officials over the Thanksgiving holiday. Her withdrawal marked a dramatic fall for a candidate who showed extraordinary promise in her bid to become the first black female president. Harris launched her campaign in front of 20,000 people on a chilly January day in Oakland, California. The first woman and first black attorney general and U.S. senator in California’s history, she was widely viewed as a candidate poised to excite the multiracial coalition of voters that sent Barack Obama to the White House. Her departure erodes the diversity of the Democratic field, which is dominated at the moment by a top tier that is white and mostly male. “She was an important voice in the race, out before others who raised less and were less electable. It’s a loss not to have her voice in the race,” said Aimee Allison, who leads She the People, a group that promotes women of color. Harris ultimately could not craft a message that resonated with voters or secure the money to continue her run. She raised an impressive $12 million in the first three months of her campaign and quickly locked down major endorsements meant to show her dominance in her home state, which offers the biggest delegate haul in the Democratic primary contest. But as the field grew, Harris’ fundraising remained flat; she was unable to attract the type of attention being showered on Pete Buttigieg by traditional donors or the grassroots firepower that drove tens of millions of dollars to Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders. In her note to supporters, Harris lamented the role of money in politics and, without naming them, took a shot at billionaires Tom Steyer and Michael Bloomberg, who are funding their own presidential bids. “I’m not a billionaire,” she said. “I can’t fund my own campaign. And as the campaign has gone on, it’s become harder and harder to raise the money we need to compete.” Harris suffered from what allies and critics viewed as an inconsistent pitch to voters. Her slogan “For the people” referenced her career as a prosecutor, a record that was viewed skeptically by the party’s most progressive voters. Through the summer, she focused on pocketbook issues and her “3 a.m. agenda,” a message that never seemed to resonate with voters. By the fall, she had returned to her courtroom roots with the refrain that “justice is on the ballot,” both a cry for economic and social justice as well as her call that she could “prosecute the case” against a “criminal” president. At times, she was tripped up by confusing policy positions; particularly on health care. After suggesting she would eliminate private insurance in favor of a fully government-run system, Harris eventually rolled out a health care plan that preserves a role for private insurance. Stumbles, often of the campaign’s making, continued to dog Harris into the winter, stymieing her ability to capitalize on solid moments. Harris kicked off November with a well-received speech at a massive Iowa dinner, just a day after her campaign announced it would fire staff at its Baltimore headquarters and was moving some people from other early states to Iowa. Her message was regularly overshadowed by campaign aides and allies sharing grievances with the news media. Several top aides decamped for other campaigns, one leaving a blistering resignation letter. “Because we have refused to confront our mistakes, foster an environment of critical thinking and honest feedback, or trust the expertise of talented staff, we find ourselves making the same unforced errors over and over,” Kelly Mehlenbacher wrote in her letter, obtained by The New York Times. Mehlenbacher now works for businessman Bloomberg’s campaign. With Harris’ exit, 15 Democrats remain in the race for the nomination. Several praised her on Tuesday. Former Vice President Joe Biden, who had a memorable debate stage tussle with Harris this summer, called the senator a “solid person, loaded with talent.” Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders commended Harris for “running a spirited and issue-oriented campaign.” New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, one of two black candidates still in the campaign, called Harris a “trailblazer.” Harris anchored her campaign in the powerful legacy of pioneering African Americans. Her campaign launch on the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday included a nod to Shirley Chisholm, the New York congresswoman who sought the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination 47 years ago earlier. One of her first stops as a candidate was to Howard University, the historically black college that she attended as an undergraduate. She spent much of her early campaign focusing on South Carolina, which hosts the first Southern primary and has a significant African American population. But Harris struggled to chip away at Biden’s deep advantage with black voters who are critical to winning the Democratic nomination. Harris and her aides believe she faced an uphill battle — and unfair expectations for perfection — from the start as a woman of color. Her campaign speech included a line about what Harris called the “donkey in the room,” a reference to the thought that Americans wouldn’t elect a woman of color. Harris often suggested it was criticism she faced in her other campaigns — all of which she won. Her departure from the presidential race marks her first defeat as a political candidate. Associated Press writers Steve Peoples in New York and Bill Barrow in Mason City, Iowa, contributed to this report. By Kathleen Ronayne and Nicholas Riccardi Associated Press. Republished with the Permission of the Associated Press.

Takeaways from the democratic presidential debate

Democrats spent more time making the case for their ability to beat President Donald Trump than trying to defeat each other in their fifth debate Wednesday night. Civil in tone, mostly cautious in approach, the forum did little to reorder the field and may have given encouragement to two new entrants into the race, Mike Bloomberg and Deval Patrick. Here are some key takeaways. IMPEACHMENT CLOUD HOVERS The impeachment inquiry of President Donald Trump took up much of the oxygen early in the debate. The questions about impeachment did little to create much separation in a field that universally condemns the president. The candidates tried mightily to pivot to their agenda. Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren talked about how a major Trump donor became the ambassador at the heart of the Ukraine scandal, and reiterated her vow to not reward ambassadorships to donors. Former Vice President Joe Biden tried to tout the investigation as a measure of how much Trump fears his candidacy. Impeachment is potentially perilous to the Democratic candidates for two reasons. A Senate trial may trap a good chunk of the field in Washington just as early states vote in February. It also highlights a challenge for Democrats since Trump entered the presidential race in 2015 — shifting the conversation from Trump’s serial controversies to their own agenda. Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders warned, “We cannot simply be consumed by Donald Trump, because if you are you’re going to lose the election.” OBAMA COALITION Perhaps more than in any debate so far, Democrats explicitly acknowledged the importance of black and other minority voters. California Sen. Kamala Harris said repeatedly that Democrats must reassemble “the Obama coalition” to defeat Trump. Harris, one of three black candidates running for the nomination, highlighted black women especially, arguing that her experiences make her an ideal nominee. Another black candidate, New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, added: “I’ve had a lot of experience with black voters. … I’ve been one since I was 18.” Neither Booker nor Harris, though, has been able to parlay life experiences into strong support in the primary, in no small part because of Biden’s strong standing in the black community. Biden’s standing is also a barrier to other white candidates, including South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg, who is surging in overwhelmingly white Iowa but struggling badly with black voters in Southern states like South Carolina that have proven critical to previous Democratic nominees. Buttigieg acknowledged as much, saying he welcomes “the challenge of connecting with black voters in America who don’t yet know me.” The exchanges show that candidates seemingly accept the proposition that the eventual nominee will have to put together a racially diverse coalition to win, and that those whose bases remain overwhelmingly white (or just too small altogether) aren’t likely to be the nominee. CLIMATE CRISIS GETS AIR The climate crisis, which Democratic voters cite as a top concern, finally gained at least some attention. There were flashes of the debate Wednesday night, as billionaire environmental activist Tom Steyer swiped at Biden by suggesting the former vice president wants an inadequate, piecemeal approach to the crisis. Biden hit right back, reminding Steyer that he sponsored climate legislation as a senator in the 1980s while Steyer built his fortune in part on investments in coal. Buttigieg turned a question about the effects of Trump’s policies on farmers into a call for the U.S. agriculture sector to become a key piece of an emissions-free economy. But those details seem less important than the overall exchange — or lack thereof. Perhaps it’s the complexities of the policies involved. Or perhaps it’s just the politics. Whatever the case, the remaining field simply doesn’t seem comfortable or willing to push climate policy to the forefront, and debate moderators don’t either. HEALTH CARE GROUNDHOG DAY Before every debate, Democratic presidential campaigns aides lay out nuanced, focused arguments their candidates surely will make on the stage. And every debate seems to evolve quickly into an argument over health care. So it was again. Within minutes of the start, Warren found herself on the defensive as she explained she still supports a single-payer government run insurance system — “Medicare for All” — despite her recent modified proposal to get there in phases. Not to be outdone, Sanders reminded people that he’s the original Senate sponsor of the “Medicare for All” bill that animates progressives. “I wrote the damn bill,” he quipped. Again. Biden jumped in to remind his more liberal rivals that their ideas would not pass in Congress. The former vice president touted his commitment to adding a government insurance plan to existing Affordable Care Act exchanges that now sell private insurance policies. The debate highlights a fundamental tension for candidates: Democratic voters identify health care as their top domestic policy concern, but they also tell pollsters their top political priority in the primary campaign is finding a nominee who can defeat Trump. The top contenders did nothing to settle the argument Wednesday, instead offering evidence that the ideological tug-of-war will remain until someone wins enough delegates to claim the nomination. DID YOU HEAR THE ONE … The debate was so genial that some of the most memorable moments were the candidates’ well-rehearsed jokes. Asked what he’d say to Russian President Vladimir Putin if he’s elected to the White House, technology entrepreneur Andrew Yang said his first words would be, “Sorry I beat your guy.” Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar drew laughs for an often-repeated anecdote about how she set a record by raising $17,000 from ex-boyfriends during her first campaign. She also pushed back at fears of a female candidacy by saying, “If you think a woman can’t beat Donald Trump, Nancy Pelosi does it every day.” Booker, criticizing Biden for not agreeing to legalize marijuana, said, “I thought you might have been high when you said it.” And Harris may have issued the zinger of the night at the president when discussing his nuclear negotiations with North Korea: “Donald Trump got

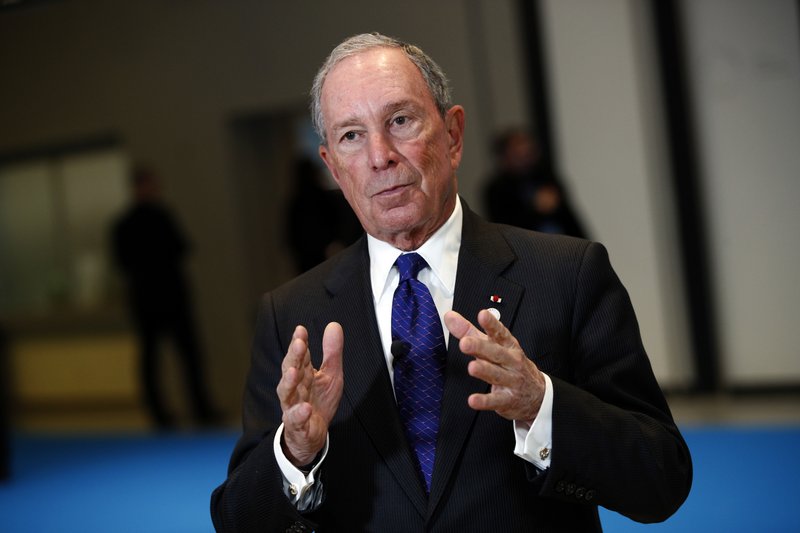

Michael Bloomberg opens door to 2020 Democratic run for president

Michael Bloomberg, the billionaire former mayor of New York City, is opening the door to a 2020 Democratic presidential campaign, warning that the current field of candidates is ill equipped to defeat President Donald Trump. Full Coverage: Election 2020 Bloomberg, who initially ruled out a 2020 run, has not made a final decision on whether to jump into the race. If he were to launch a campaign, it could dramatically reshape the Democratic contest less than three months before primary voting begins. The 77-year-old has spent the past few weeks talking with prominent Democrats about the state of the 2020 field, expressing concerns about the steadiness of former Vice President Joe Biden’s campaign and the rise of liberal Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, according to people with knowledge of those discussions. In recent days, he took steps to keep his options open, including moving to get on the primary ballot in Alabama ahead of the state’s Friday filing deadline. In a statement on Thursday, Bloomberg adviser Howard Wolfson said the former mayor believes Trump “represents an unprecedented threat to our nation” and must be defeated. “But Mike is increasingly concerned that the current field of candidates is not well positioned to do that,” Wolfson said. Bloomberg’s moves come as the Democratic race enters a crucial phase. Biden’s front-runner status has been vigorously challenged by Warren and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, who are flush with cash from small-dollar donors. But both are viewed by some Democrats as too liberal to win in a general election faceoff with Trump. Despite a historically large field, some Democrats anxious about defeating Trump have been looking for other options. Former Attorney General Eric Holder and former Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick have quietly had conversations with supporters urging them to consider a run, but neither appears likely to get in the race. Bloomberg, a Republican-turned-independent who registered as a Democrat last year, has flirted with a presidential run before but ultimately backed down, including in 2016. He endorsed Hillary Clinton in that race and, in a speech at the Democratic Party convention, pummeled Trump as a con who has oversold his business successes. Bloomberg plunged his efforts — and his money — into gun control advocacy and climate change initiatives. He again looked seriously at a presidential bid earlier this year, traveling to early voting states and conducting extensive polling, but decided not to run in part because of Biden’s perceived strength. Biden did not address Bloomberg’s potential candidacy at a fundraiser Thursday night in Boston. With immense personal wealth, Bloomberg could quickly build out a robust campaign operation across the country. Still, his advisers acknowledge that his late entry to the race could make competing in states like Iowa and New Hampshire, which have been blanketed by candidates for nearly a year, difficult. Instead, they previewed a strategy that would focus more heavily on the March 3 “Super Tuesday” contests, including in delegate-rich California. Some Democrats were skeptical there would be a groundswell of interest in the former New York mayor. “There are smart and influential people in the Democratic Party who think a candidate like Bloomberg is needed,” said Jennifer Palmieri, who advised Clinton’s 2016 campaign. “But there is zero evidence that rank-and-file voters in the early states of Iowa and New Hampshire feel the same.” Still, others credited Bloomberg with taking on “some of America’s biggest challenges” and finding success. “While this is not an endorsement, Michael Bloomberg is a friend and I admire his track record as a successful business leader and Mayor who finds practical solutions to some of America’s biggest challenges, from creating good jobs to addressing the opioid crisis and fighting for common-sense gun safety,” said Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo, a Democrat. Bloomberg reached out to several prominent Democrats on Thursday, including Raimondo. One Democrat Bloomberg hasn’t spoken to as he’s reconsidered his run is former President Barack Obama. Bloomberg would pose an immediate ideological challenge to Biden, who is running as a moderate and hopes to appeal to independents and Republicans who have soured on Trump. But the billionaire media mogul with deep Wall Street ties could also energize supporters of Warren and Sanders, who have railed against income inequality and have vowed to ratchet up taxes on the wealthiest Americans. “He’s a literal billionaire entering the race to keep the progressives from winning,” said Rebecca Katz, a New York-based liberal Democratic strategist. “He is the foil.” Warren on Thursday tweeted: “Welcome to the race, @MikeBloomberg!” and linked to her campaign website, saying he would find there “policy plans that will make a huge difference for working people and which are very popular.” Bloomberg would face other challenges as well, particularly scrutiny of his three terms as mayor. He has defended the New York Police Department’s use of the controversial stop-and-frisk policy that has been criticized as targeting African Americans and Hispanics. Black voters in particular are one of the most powerful constituencies in Democratic politics. Bloomberg will have to move quickly in the coming days and weeks to get on the ballot in many of the primary states, including Alabama. New Hampshire’s filing deadline is Nov. 15. In Arkansas, another Super Tuesday state, a Democratic Party spokesman said a person representing a “mystery candidate” reached out Thursday afternoon asking about the requirements to join the ballot. Reed Brewer, communications director for the Arkansas Democrats, said he walked the individual through the process — which simply requires filing documentation with both the state party and secretary of state, as well as paying a $2,500 fee — and was assured that the fee would be “no problem” for the mystery candidate. There is no filing requirement for a candidate to run in the Iowa caucuses, which are a series of Democratic Party meetings, not state-run elections. It means a candidate can enter the race for the Feb. 3 leadoff contest at any time. Associated Press writers Jill Colvin in Washington; Alexandra Jaffe and Thomas Beaumont in Des Moines,

Takeaways: Elizabeth Warren under fire, 70s club ignores the age issue

A dozen democratic presidential candidates participated in a spirited debate over health care, taxes, gun control and impeachment. Takeaways from the three-hour forum in Westerville, Ohio: WARREN’S RISE ATTRACTS ATTACKS Sen. Elizabeth Warren found Tuesday that her rise in the polls may come with a steep cost. She’s now a clear target for attacks, particularly from more moderate challengers, and her many plans are now being subjected to much sharper scrutiny. Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar and South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg slammed her for not acknowledging, as Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders has, that middle-class taxes would increase under the single-payer health plan she and Sanders favor. “At least Bernie’s being honest with this,” Klobuchar said. “I don’t think the American people are wrong when they say what they want is a choice,” Buttigieg told Warren. His plan maintains private insurance but would allow people to buy into Medicare. Candidates also pounced on Warren’s suggestion that only she and Sanders want to take on billionaires while the rest of the field wants to protect them. Former Texas Rep. Beto O’Rourke told Warren it didn’t seem as though she wanted to lift people up and she is “more focused on being punitive.” And they piled onto her signature proposal, a 2 percent wealth tax to raise the trillions of dollars needed for many of her ambitious proposals. Technology entrepreneur Andrew Yang noted that such a measure has failed in almost every European country where it’s been tried. Sen. Kamala Harris of California even went after Warren for not backing Harris’ call for Twitter to ban President Donald Trump. THAT 70s SHOW The stage included three 70-something candidates who would be the oldest people ever elected to a first term as president — including 78-year-old Sanders, who had a heart attack this month. Moderators asked all three how they could do the job. None really addressed the question. Sanders invited the public to a major rally he’s planning in New York City next week and vowed to take the fight to corporate elites. Biden promised to release his medical records before the Iowa caucuses next year and said he was running because the country needs an elder statesman in the White House after Trump. Warren, whose campaign has highlighted her hours-long sessions posing for selfies with supporters, promised to “out-organize and outlast” any other candidate, including Trump. Then she pivoted to her campaign argument that Democrats need to put forth big ideas rather than return to the past, a dig at Biden. ONE VOICE ON IMPEACHMENT The opening question was a batting practice fastball for the Democratic candidates: Should Trump be impeached? They were in steadfast agreement. All 12 of them. Largely with variations on the word “corrupt” to describe the Republican president. Warren was asked first if voters should decide whether Trump should stay in office. She responded, “There are decisions that are bigger than politics.” Biden, who followed Sanders, offered a rare admission: “I agree with Bernie.” The only hint of dissonance came from Rep. Tulsi Gabbard of Hawaii, who was one of the last Democratic House members to back an impeachment inquiry. She lamented that some Democrats had been calling for Trump’s impeachment since right after the 2016 election, undermining the party’s case against him. KLOBUCHAR: MINNESOTA NOT-SO-NICE Klobuchar has faded into the background in previous debates, but she stood out on the crowded stage. She also went on the attack. She chided Yang for seeming to compare Russian interference in the 2016 election to U.S. foreign policy. But her main barbs were reserved for Warren. “I appreciate Elizabeth’s work but, again, the difference between a plan and a pipe dream is something you can actually get done,” she said. After Warren seemed to suggest other candidates were protecting billionaires, Klobuchar pounced. “No one on this stage wants to protect billionaires,” Klobuchar said. “Even the billionaire doesn’t want to protect billionaires.” That was a reference to investor Tom Steyer, who had agreed with Sanders’ condemnation of billionaires and called for a wealth tax — despite the fact that his wealth funded his last-minute campaign to clear the debate thresholds and appear Tuesday night. Klobuchar also forcefully condemned Trump’s abandonment of the Kurds in Syria. BOOKER THE PEACEMAKER New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker has been trying to campaign on the power of love and unity. It hasn’t vaulted him to the top of the polls, but it drew perhaps the biggest cheers from the crowd Tuesday night. As candidates bickered over their tax plans, Booker shut it down. “We’ve got one shot to make Donald Trump a one-term president and how we talk about each other in this debate actually really matters,” he said. “Tearing each other down because we have a different plan is unacceptable.” Later, as candidates tussled over foreign policy and Syria, Booker again tried to bring the debate back to morals. “This president is turning the moral leadership of this country into a dumpster fire,” he said, before launching into a furious condemnation of Trump’s foreign policy. The New Jersey senator’s inability to break out of the pack has puzzled Democrats who long saw him as a top-tier presidential candidate. By Nicholas Riccardi Associated Press Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.