Former AP civil rights reporter Kathryn Johnson dies

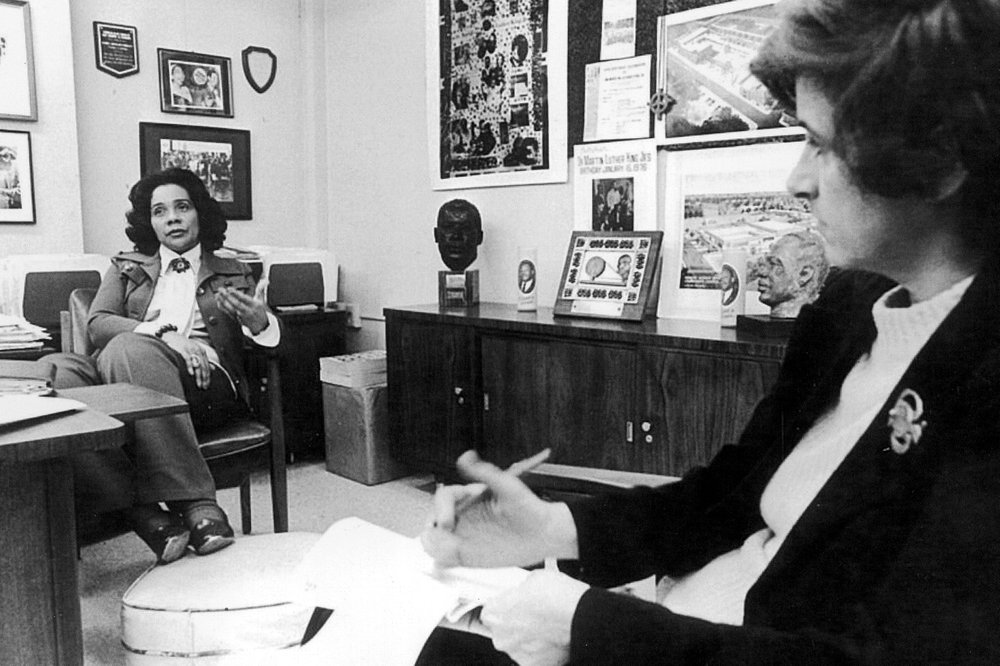

Kathryn Johnson, a trailblazing reporter for The Associated Press whose intrepid coverage of the civil rights movement and other major stories led to a string of legendary scoops, died Wednesday. She was 93. Her niece, Rebecca Winters, said Johnson died Wednesday morning in Atlanta. Johnson was the only journalist allowed inside Martin Luther King Jr.’s home the day he was assassinated. When Gov. George Wallace blocked black students from entering the University of Alabama, she sneaked in to cover his confrontation with federal officials. She scored exclusive interviews with 2nd Lt. William L. Calley Jr. before he was convicted of his role in the My Lai massacre. “I was never ambitious, really, anxious to make money …,” she told an interviewer for an AP oral history project in 2007. Johnson said she didn’t want to be bored and added, “in most of my career, I really wasn’t.” That career spanned a half-century, from the era of reporters racing each other to pay phones to the birth of 24-hour cable television news. She began covering King when he was a little-known Baptist preacher from Atlanta. She had also written about his wife, Coretta, who was a talented singer. The evening of April 4, 1968, Johnson and a date were on their way to the movies when news of the assassination came over the radio. When she arrived at the King house, two reporters were chatting with a police officer on the porch. The front door opened, and Johnson could see Coretta Scott King in a pink nightgown, standing in the hall. “She spotted me and said, ‘Let Kathryn in,’” she recalled. Johnson was at the home every day, giving the AP several scoops — including an 11-hour beat over archrival United Press International on the funeral arrangements. She later wrote the book “My Time With the Kings,” which was published in 2016 and recollected her time covering the civil rights movement. “Kathryn Johnson was essential reading on one of the most important stories of the 20th century, and she did it by being at the center of the action, close to the most important newsmakers,” AP Executive Editor Sally Buzbee said. Born in Columbus, Georgia, Johnson graduated from Agnes Scott College, a private, all-woman school in Decatur, Georgia, in 1947. In December of that year, she dropped by the local AP office looking for a job; she was offered a secretarial position. “I think she was an unknown pioneer in that field,” Winters said. Twelve years later, after the American Newspaper Guild interceded, Johnson was finally given a writing job. She said she got the civil rights beat because the men “did not want to cover a black movement.” “When my aunt was interested in this young preacher named Martin Luther King, the men in journalism didn’t want anything to do with a black man and interviewing him,” Winters said. “She was just enthralled with the man, before he was famous.” Her first big story was Charlayne Hunter’s integration of the University of Georgia in January 1961. Still youthful looking at 34, she impersonated a student to get close to Hunter. In June 1963, Johnson was in Tuscaloosa, where Wallace blocked the entrance of the University of Alabama’s Foster Auditorium to black students. She and the other reporters were ushered into a large room and locked in. She went to the door and told the young patrolman that she had to use the “ladies room.” She went to the front doorway where Wallace and Deputy U.S. Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach were talking, and slipped under a large table set up for microphones. She was just a couple of feet from Wallace’s legs. For Christmas in 1969, Johnson was asked to interview the wives of Navy men missing in action or held captive in North Vietnam. Among them was Navy Capt. Jeremiah Denton, among the first prisoners of war to return home in 1973. “When my father came home, she became very close to our family and covered my father,” Denton’s daughter, Mary Denton Lewis, recalled. “He trusted Kathryn more than any other reporter because of her close relationship with my mom.” Denton retired with the rank of Rear Admiral and later served in the U.S. Senate.From late 1970 to early 1971, she covered the hearings and courts-martial stemming from the March 1968 massacre of Vietnamese civilians at the village of My Lai, and developed a rapport with Calley, the officer charged with the slaughter. Before the verdict, she persuaded Calley to give her two interviews: One for an acquittal, another for a conviction. She left the AP in 1979 to take an associate editor’s position at U.S. News & World Report. In 1988, she joined CNN, working there full time until 1999. Associated Press writers Bernard McGhee and Jeff Martin in Atlanta contributed to this report. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Daniel Sutter: The games donors and universities play

Controversies over gifts at two SEC schools, Alabama and Missouri, have recently attracted attention. The cases highlight the tension between donor goals and university administration and relate, I think, to conservatives’ increasingly dim view of higher education. Let’s consider the Alabama case first. In June, the trustees returned the largest single gift in school history, $26 million from Hugh Culverhouse Jr. (only $21 million had then been received). Mr. Culverhouse was the school’s largest donor; the business school is named for his late father, the long-time Tampa Bay Buccaneers owner, Alabama grad, and large donor. Alabama named the law school for Mr. Culverhouse. The return occurred after Mr. Culverhouse called for an out-of-state student boycott over Alabama’s new abortion law, but was apparently due to attempts to influence law school operations, allegedly including student admissions and faculty hiring. According to emails, Mr. Culverhouse may have had good intentions. He was unhappy with the quality of candidates for a constitutional law professorship and perhaps hoped that his gift could enable a hire to boost the law school’s national profile. The resolution here seems quite honorable; if you discover that you and your partners have irreconcilable expectations, you should shake hands and part ways. The Missouri case starts in 2002 with a $5 million gift from the estate of Sherlock Hibbs to fund professorships in Austrian economics. Instead Missouri funded positions for business professors with research unconnected to Austrian economics. This is where things get fascinating. Mr. Hibbs’ will included a provision that if the money were not used to hire Austrian economists, the gift would go to Hillsdale College instead. (Note to interested donors: Troy University has a strong program in Austrian economics!) Hillsdale recently sued to force the transfer, generating publicity. Missouri produced statements signed by the professors attesting that they are adherents of Austrian economics. Donors have long accused universities of using gifts to hire conservative and free-market professors for other purposes. I think this is related to the partisan decline in confidence in higher education. A 2019 Pew Center study found that 59 percent of Republicans held a negative view of higher education versus 33 percent positive, compared with 67 percent positive and 18 percent negative among Democrats. In 2015, 54 percent of Republicans viewed higher ed positively, versus 37 percent negatively. I do not believe that ignoring conservative donor intent caused this attitude shift. It likely reflects broader social forces and our general political polarization. Using gifts from conservatives to further liberal goals enables such an attitude change. What limits should be placed on gifts, or what kinds of influence should donors be able to buy? The recent college admissions scandal, with parents paying to get their children in some of our nation’s most prestigious universities, highlights these questions. (For full disclosure, the Johnson Center at Troy is supported by donors.) Professors, myself included, typically insist that admissions, curriculum, and hiring decisions be ours alone, and for good reason. We are the experts and know the most about judging faculty qualifications or different approaches in our fields. Being hired and tenured provides us specific responsibility for these decisions. State universities largely governed by faculty will better spend our tax dollars. The decision-making authority for universities though lies with the trustees or regents, as delegated to presidents or chancellors. And state universities ultimately belong to the taxpayers. Limiting faculty government is wise as professors’ views are at least somewhat biased by self-interest, and we have difficulty recognizing when we are clinging to unreasonable positions. Furthermore, our jobs provide us relatively little feedback about the contribution of our teaching and research to society. Reasonable people can disagree about the proper extent of donor influence. But accepting money under false pretenses is not right. In a perfect world, only the offenders’ names would be sullied; in our world, reputations are collective. Trampling donor intent damages the standing of higher education. Daniel Sutter is the Charles G. Koch Professor of Economics with the Manuel H. Johnson Center for Political Economy at Troy University and host of Econversations on TrojanVision. The opinions expressed in this column are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of Troy University.

The diplomat took notes. Then he told a story.

A secret cable. A disembodied voice. A coded threat. William Taylor, a career diplomat, went behind closed doors in the basement of the Capitol on Tuesday and told a tale that added up to the ultimate oxymoron — a 10-hour bureaucratic thriller. His plot devices were not cloak and dagger, but memos, text messages — and detailed notes. His testimony was laden with precision — names, dates, places, policy statements and diplomatic nuance, not typically the stuff of intrigue. But from the moment Taylor revealed that his wife and his mentor had given him conflicting advice on whether he should even get involved, the drama began to unfold. Their counsel split like this: Wife: no way. Mentor: do it. The mentor won out — or the story would have ended there. Instead, on June 17, Taylor, a West Point graduate, Vietnam veteran and tenured foreign service officer, arrived in Ukraine’s capital of Kyiv as the chief of mission. He had been recalled to service after the U.S. ambassador to Ukraine had been forced out. That alone offered foreshadowing of troubles to come. And, soon enough, Taylor said in his written opening statement, he discovered “a weird combination of encouraging, confusing and ultimately alarming circumstances.” The story Taylor related from there amounted to a detailed, almost prosecutorial, rejoinder to White House efforts to frame President Donald Trump’s actions in Ukraine as perfectly normal and unworthy of an impeachment investigation. With each documented conversation, he made it harder for the president to press his argument that there was no quid pro quo in which he held up military aid to advance his political interests. Over three months, Taylor told legislators, he fought his way through a maze of diplomatic channels and rival backchannels as he tried to unravel the story behind the mysterious hold-up of $400 million in U.S. military aid that Ukraine desperately needed in order to defend itself against the Russians. First came mixed signals about whether Trump would follow through on his promise to invite Ukraine’s new president, Volodymyr Zelenskiy, to meet with him in the Oval Office. Taylor was told by other U.S. diplomats that Trump needed “to hear from” Zelenskiy before the meeting would be scheduled. And that Zelenskiy needed to make clear he was not standing in the way of “investigations.” Next, Taylor wrote, there was “something odd:” Gordon Sondland, a Trump ally and U.S. ambassador to the European Union, “wanted to make sure no one was transcribing or monitoring” a June 28 call that the diplomats made to Zelenskiy. Soon enough, Taylor was detecting that Zelenskiy’s hopes of snagging the coveted Oval Office meeting were contingent on the Ukrainian leader agreeing to investigate Democrats in the 2016 election and to look into a Ukrainian company linked to the family of Trump political foe Joe Biden. “It was clear that this condition was driven by the irregular policy channel I had come to understand was guided by Mr. Giuliani,” Taylor said, referring to Rudy Giuliani, the former New York City mayor and Trump lawyer who was involving himself in Ukrainian affairs. The dueling channels of communication were highly unusual. Then things got more strange: Toward the end of a routine July 18 video conference with National Security Council officials in Washington, “a voice on the call” from an unknown person who was off-screen announced that the Office of Management and Budget would not approve any more U.S. security aid to Ukraine “until further notice.” “I and others sat in astonishment,” Taylor recounted. From there, Taylor made his way through a confusing web of conversations, text messages, cables and other contacts trying to figure out why this was happening. His diplomatic parrying was punctuated by a detour to the front lines of the Russia-Ukraine fighting in northern Donbas, where Taylor witnessed firsthand “the armed and hostile Russia-led forces on the other side of the damaged bridge across the line of contact.” That frozen military aid was no mere abstraction. “More Ukrainians would undoubtedly die without the U.S. assistance,” Taylor wrote.The diplomat was so troubled that he requested a private meeting with John Bolton when the national security adviser visited Kyiv in late August. Bolton’s counsel to Taylor: Send a “first-person cable” to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo laying out his concerns. Taylor took the advice and sent a secret cable describing the “folly” of withholding assistance. He got no specific response. He still couldn’t explain to the Ukrainians why they weren’t getting their aid. And time was running out: If the assistance wasn’t delivered by Sept. 30, the end of the government’s fiscal year, it would vanish. In early September, the puzzle pieces began to fit together. It wasn’t just the Oval Office meeting that was contingent on Zelenskiy investigating Democrats, Taylor learned, it was the military aid. Taylor said Sondland told him that if Zelenskiy didn’t publicly announce the investigations, there would a “stalemate.” He took “stalemate” to be code for holding up the assistance. Taylor’s text messages take the story forward: “I think it’s crazy to withhold security assistance for help with a political campaign,” he wrote to Sondland. Sondland waited five hours to respond with a clinical denial of any such contingency: “The President has been crystal clear no quid pro quo’s of any kind.” He reportedly talked to Trump before he sent the response. The explanation didn’t satisfy Taylor. But, at last, on Sept. 11, Taylor got word that the hold on releasing the money had been lifted and the security assistance would be provided. Taylor summed up his tale as “a rancorous story about whistleblowers, Mr. Giuliani, side channels, quid pro quos, corruption, and interference in elections.” Democrats found it riveting, with Rep. Raja Krishnamoorthi of Illinois describing Taylor as “like a witness out of central casting.” White House press secretary Stephanie Grisham, though, dismissed it as part of a “coordinated smear campaign from far-left lawmakers and radical unelected bureaucrats waging war on the Constitution.” In the end, Taylor said he

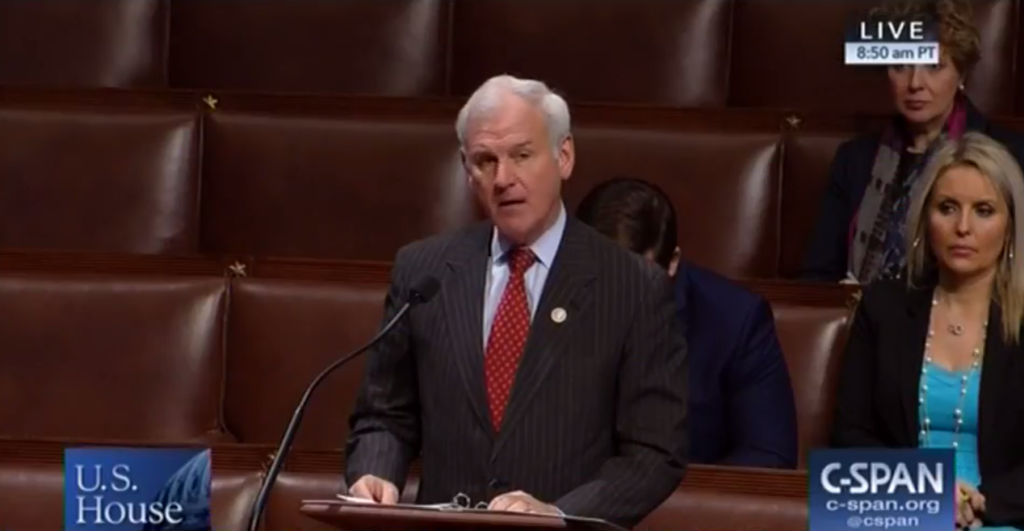

Bradley Byrne: How do you solve a problem like Syria?

Recent developments in Syria highlight the need for the United States to revisit its broader Middle Eastern policy. Early last week, I joined a small meeting of House Republicans for an update on Syria from Secretary of Defense Mark Esper where he discussed a phone call from President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey to President Donald Trump. During that call, Erdogan notified President Trump that after years of waiting at the Syrian border, Turkish troops would finally cross over. He assured that Turkey was not coming after our troops but targeting certain Kurdish factions they consider terrorists. He gave President Trump 48 hours to relocate the two dozen or so American troops stationed on the border. President Trump was faced with a difficult decision. Ultimately, he decided to remove American servicemembers from harm’s way to prevent a full-blown conflict with Turkey. Turkey’s incursion into Syria is wrong and very troubling. Erdogan should never treat our President and our country the way he did on the phone call. There will be serious consequences for his behavior. I support seeking methods of leverage with Turkey that do not endanger our troops. After President Trump proposed harsh economic sanctions, the administration negotiated a cease fire with Turkey. The cease fire has been shaky at best, but it probably prevented many more deaths in the region. This is happening in the context of a greater strategic problem in the Middle East. For at least a decade, we’ve lacked a well-defined mission. What are our interests in the Middle East? What do we do to pursue and protect those interests? Since coming to Congress and serving on the House Armed Services Committee, I have not seen a strategic, conventional interest for the U.S. in Syria, other than destroying the ISIS caliphate. To be sure, Kurdish forces were the largest part of the successful campaign against the caliphate, and we need to stand by them as best we can under these challenging circumstances. But Syria is a failed state. It is bewildering the number of groups in some form of combat. With so many factions, it is often difficult to know who the good guys are. Problems between the Turks and Kurds will persist for generations, but this dispute is one of many combustible problems in the Middle East today. Just weeks ago, Iran attacked our Saudi Arabian ally. We need to work with our allies to determine our strategic goals and how to reach them. We should continue providing assistance to our allies, including the Kurds, but progress requires buy-in from all of our allies in the region. Turkey, as a NATO member, does currently play a role in supporting our alliance goals. Turkey is the home of an important U.S. air base and many other critical NATO assets including U.S. nuclear weapons. However, Turkey’s actions cast serious doubts on whether they will honor their NATO commitments going forward, and frank discussions between Trump, Erdogan and other NATO leaders are needed. We must be tough with Turkey. I still believe strong sanctions to weaken and punish Turkey are needed, and I signed on as an original cosponsor to Liz Cheney’s resolution to impose very tough sanctions. After the Turkish incursion, I was disappointed that the House hastily put forward a resolution condemning President Trump’s actions without knowing the full facts. The very next day, I received a classified briefing shedding more light on his tough decision. I think everyone in Congress should have access to these classified briefings to gain a fuller understanding of what happened. Instead of attacking the President, we need to have sincere bipartisan conversations and propose concrete solutions for Syria and the Middle East. On critical national security issues, we must put America first.