No sign of Donald Trump’s replacement for obamacare

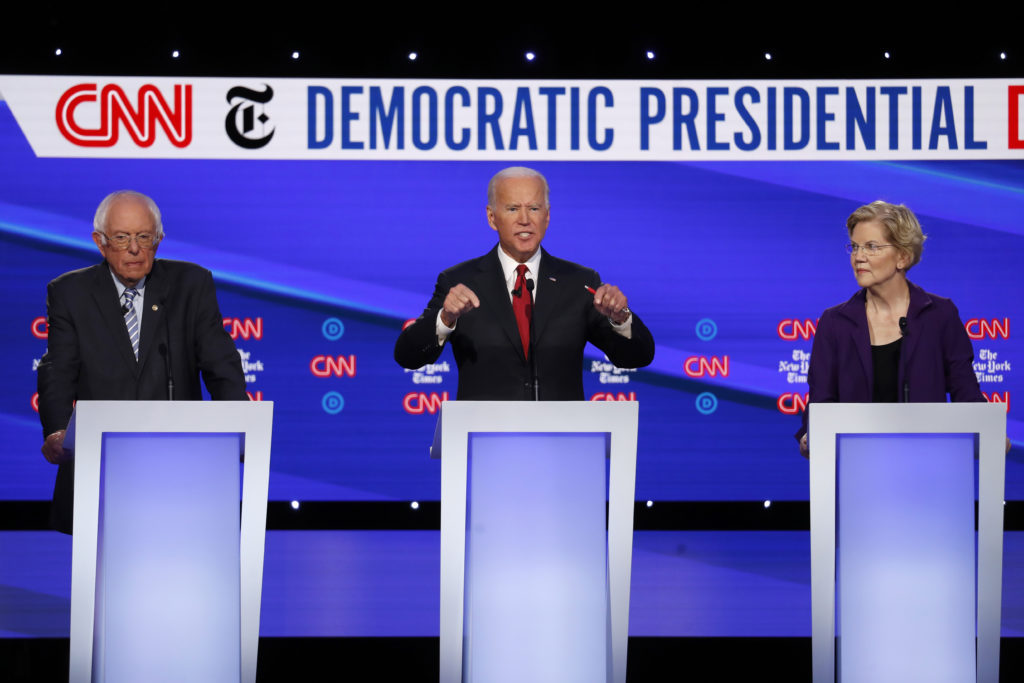

As a candidate for the White House, Donald Trump repeatedly promised that he would “immediately” replace President Barack Obama’s health care law with a plan of his own that would provide “insurance for everybody.” Back then, Trump made it sound that his plan — “much less expensive and much better” than the Affordable Care Act — was imminent. And he put drug companies on notice that their pricing power no longer would be “politically protected.” Nearly three years after taking office, Americans still are waiting for Trump’s big health insurance reveal. Prescription drug prices have edged lower, but with major legislation stuck in Congress it’s unclear if that relief is the start of a trend or merely a blip. Meantime the uninsured rate has gone up on Trump’s watch, rising in 2018 for the first time in nearly a decade to 8.5 percent of the population, or 27.5 million people, according to the Census Bureau. “Every time Trump utters the words ACA or Obamacare, he ends up frightening more people,” said Andy Slavitt, who served as acting administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services during the Obama administration. He’s “deepening their fear of what they have to lose.” White House officials argue that the president is improving the health care system in other ways, without dismantling private health care. White House spokesman Judd Deere noted Trump’s signing of the “Right-to-Try” act that allows some patients facing life-threatening diseases to access unapproved treatment, revamping the U.S. kidney donation system and the FDA approving more generic drugs as key improvements. Trump has also launched a drive to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic. “The president’s policies are improving the American health care system for everyone, not just those in the individual market,” Deere said. But as Trump gears up for his reelection campaign, the lack of a health care plan is an issue that Democrats believe they can use against him. Particularly since he’s still seeking to overturn “Obamacare” in court. This month, a federal appeals court struck down the ACA’s individual mandate, the requirement that Americans carry health insurance, but sidestepped a ruling on the law’s overall constitutionality. The attorneys general of Texas and 18 other Republican-led states filed the underlying lawsuit, which was defended by Democrats and the U.S. House. Texas argued that due to the unlawfulness of the individual mandate, “Obamacare” must be entirely scrapped. Trump welcomed the ruling as a major victory. Texas v. United States appears destined to be taken up by the Supreme Court, potentially teeing up a constitutional showdown before the 2020 presidential election. In a letter Monday to Democratic lawmakers, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi singled out the court case. “The Trump administration continues to firmly support the recent ruling in the 5th Circuit, which they hope will move them one step closer to obliterating every protection and benefit of the Affordable Care Act,” Pelosi wrote, urging Democrats to keep health care front and center in 2020. Accused of trying to dismantle his predecessor’s health care law with no provision for millions who depend on it, Trump and senior administration officials have periodically teased that a plan was just around the corner. In August, the administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Seema Verma, said officials were “actively engaged in conversations and working on things,” while Trump adviser Kellyanne Conway suggested that same month an announcement was on the horizon. In June, Trump told ABC News that he’d roll out his “phenomenal health care plan” in a couple of months, and that it would be a central part of his reelection pitch. The country is still waiting. Meantime Trump officials say the administration has made strides by championing transparency on hospital prices, pursuing a range of actions to curb prescription drug costs, and expanding lower-cost health insurance alternatives for small businesses and individuals. One of Trump’s small business options — association health plans — is tied up in court. And taken together, the administration’s health insurance options are modest when compared with Trump’s original goal of rolling back the ACA. Since Trump has not come through on his promise of a big plan, internecine skirmishes among 2020 Democratic presidential hopefuls have largely driven the health care debate in recent months. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren are leading the push among liberals for a “Medicare for All” plan that would effectively end private health insurance while more moderate candidates, like Joe Biden, Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar, advocate for what they contend is a more attainable expansion of Medicare. Brad Woodhouse, a former Democratic National Committee official and executive director of the Obamacare advocacy group Protect Our Care, said it is important for Democrats to “put down the knives they’ve been wielding against one another on health care.” “Instead turn their attention to this president and Republicans who are trying to take it away,” Woodhouse counseled. Some Democratic hopefuls appear to be doing just that. During a campaign stop in Memphis, Tennessee. this month, former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg called out Trump on health care, saying the president is “determined to throw Americans off the boat, without giving them a lifeline.” Polling suggests Trump’s failure to follow through on his promise to deliver a revamped health care system could be a drag on his reelection effort. Voters have consistently named health care as one of their highest concerns in polling. And more narrowly, a recent Gallup-West Health poll found that 66 percent of adults believe the Trump administration has made little or no progress curtailing prescription drug costs. Prescription drug prices did drop 1 percent in 2018, according to nonpartisan experts at U.S. Health and Human Services. That was the first such price drop in 45 years, driven by declines for generic drugs, which account for nearly 9 out of 10 prescriptions dispensed. Prices continued to rise for brand-name drugs, although at a more moderate pace. Trump’s broadsides against the pharmaceutical industry might well have helped check prices, though drug companies have

2020 Watch: Messy primary finally meets election year

The presidential politics calendar turned to 2020 nearly a year ago. This week, the actual date catches up. What we’re watching as the preseason closes and election year opens: Days to Iowa caucuses: 35 Days to general election: 309 THE NARRATIVE The ups, downs and swerves of 2019 yielded a stable top slate. Former Vice President Joe Biden leads most national polls of Democratic primary voters, with Sens. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts within striking distance. Yet in the first caucus state of Iowa and the first primary state of New Hampshire, there’s a jumble of Biden, Sanders, Warren and Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Indiana. At first glance, it’s a clean choice: Biden and Buttigieg hail from the center-left; Warren and Sanders come from the progressive left. Reality is more layered. All four have weaknesses within Democrats’ diverse electorate; each makes a different case for carrying the banner against President Donald Trump, who is now impeached but a near certainty to survive a Senate trial. If that’s not enough indecision, several wildcards — including two billionaires — still hope to scramble the contest. THE BIG QUESTIONS Money: Who can (sort of) compete with Michael Bloomberg’s wallet? The fourth-quarter fundraising period ends Tuesday. Warren and Sanders set the early curve for grassroots donations, outpacing Buttigieg and Biden, who tap traditional deep-pocketed contributors in addition to online donors. Now those small-donor juggernauts must compete with former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who’s used a share of his estimated $50 billion personal fortune to blanket television and digital advertising and build an expansive staff in Super Tuesday states. For his rivals, it’s not so much about keeping up; Bloomberg can easily outspend every other campaign, including that of fellow billionaire Tom Steyer. But there’s only so much television time for sale, and if Warren and Sanders want to plow big money into Super Tuesday, especially the expensive television markets of California, they’ll need as much cash as possible ahead of time. Biden, meanwhile, has already secured his best fundraising quarter (a relative comparison for a candidate who’s lagged other top-tier contenders). The question is whether Biden’s “best” mollifies establishment Democrats who waved red flags when he reported having less than $9 million on hand at September’s end. Money, Part II: How long can Cory Booker keep going? The year-end deadline is critical for New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker as he reaches for relevance. The last of two African American candidates (along with former Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick), Booker made a do-or-die money appeal in September, and it worked. But it’ll take more than scraping by to fund the turnaround he envisions: a surprise finish in overwhelmingly white Iowa to kick-start a dramatic rise in more diverse primary states that follow (Barack Obama’s 2008 path). Campaigns that hit big fundraising numbers tend to leak that news before Federal Election Commission filings are due. Candidates with bad news tend to wait. So, it bears watching how Booker’s team plays it to start January. Is Amy Klobuchar being overlooked in Iowa? Those previously mentioned Iowa and New Hampshire jumbles omit Amy Klobuchar. But the Minnesota senator is plugging away in both states. She just hit her 99th Iowa county (that’s all of them), demonstrating her effort to use complex caucus rules that can reward candidates with a wide geographic footprint. Notably, Klobuchar’s strategy tracks Biden. Both aim for a more consistent appeal across 1,679 precincts than Warren, Sanders and Buttigieg muster on Feb. 3. The question becomes how many precincts give both Biden and Klobuchar the minimum 15 percent support required to count toward delegates. Anyone who doesn’t hit that viability mark drops from subsequent ballots, their backers going up for grabs. Biden’s Iowa hopes depend in part on picking up moderates on realignment votes (read: Klobuchar and Buttigieg supporters). If Klobuchar is as strong as she hopes to be, she could turn that strategy around on Biden, driving him below viability and attracting his supporters on later ballots. Biden returns to Iowa this week for another bus tour, though not as lengthy as his eight-day jaunt after Thanksgiving. Is Sanders a true contender this time? Sanders lost the 2016 nomination because of Hillary Clinton’s advantage among non-white Democrats. Since then, Sanders has deepened his ties among Latinos, African Americans and other non-whites. Warren and Buttigieg are still chasing that success. Sanders’ advisers believe the senator is well-positioned to challenge Biden among non-whites if he’s able to build early momentum in New Hampshire and Iowa, where Sanders will spend New Year’s Eve. If they’re right, that would open avenues to delegates Sanders didn’t get in 2016. Is Trump’s position improving? The president has never been popular judged in a vacuum. In 2016, he won GOP primaries with pluralities and lost the general election popular vote. As president, he’s never reached majority job approval in Gallup’s polling. But he’s still hovering in the 40s, not far from where his immediate predecessors were 11 months before winning second terms. Impeachment proceedings haven’t affected Trump’s standing. Meanwhile, the same Democratic-run House that impeached him approved his new North America trade pact. Top-line economic numbers shine, even if the on-ground reality is uneven. And Trump could be on the cusp of a peace deal in Afghanistan after the Taliban ruling council on Sunday agreed to a temporary cease-fire. As frenetic as Trump’s messaging is, he proved in 2016 that he relishes framing binary choices for voters, and he’s more than convinced he has a case in 2020. THE FINAL THOUGHT Most voters are just tuning into a presidential race that’s raged for a year. They’ll find a Democratic contest featuring stark options on policy and personality, but lacking an undisputed favorite. Candidates are navigating primary politics: dancing along the progressive-liberal-moderate spectrum and carefully choosing when to go after each other. At the same time, Trump dominates the 2020 narrative, a fact demonstrated most recently as Biden spent two days talking about whether he’d testify in a Senate trial on Trump’s removal from office.