Adam MacLeod: Legislatures must secure our most fundamental rights

Beware of those who speak eagerly of crises. In a true crisis, we reasonably but temporarily hand our powers of practical reasoning and self-governance over to those who are most capable of diverting the threat. In an emergency, a competent executive directs the war, quarantine, or relief efforts by telling us what not to do, what to do, and how to do it. That is a fearsome power, though sometimes necessary. To exercise an emergency power is to exercise dominion over other beings who are created in the image of God. It is to presume to know both what is the best goal for one’s fellow citizens and how best to achieve it. No one should ever desire to overcome fellow human beings’ capacity to reason for themselves. Reasoning well and governing ourselves is what makes humans unique, bearers of natural and civil rights. Emergency powers deprive citizens of a most fundamental right, the right to think and act for themselves as they go about doing good things in their communities. A true leader will therefore view a crisis as something to be avoided and will feel the conferral of emergency powers as a burden to be borne reluctantly and only as long as necessary. On the other hand, an aspiring tyrant is always on the lookout for crises, whether real, imagined, or exaggerated. For someone who craves power to direct the lives of others, a crisis is an opportunity, rather than a burden. American constitutional framers, and the English and American jurists from whom they learned, knew that throughout history tyrants have seized absolute powers in moments of crisis. And tyrants do not relinquish those rights willingly once they have taken the people’s rights of self-governance away. Tyrants use a few, standard tricks to hold on to their consolidated powers longer than necessary. One is to lengthen the emergency. This can be accomplished by defining objectives in amorphous terms, or not at all. If the people do not know what the executive official is supposed to achieve with the emergency powers then the emergency can be stretched out indefinitely. A tyrannical official can heighten a crisis and expand emergency powers by villainizing critics. Anyone who expresses skepticism of the official is portrayed as an enemy of the people, selfish and unwilling to make the sacrifices necessary to combat the threat. This strategy works really well when elite media and public intellectuals are sympathetic with the official’s ideological dogmas and are willing to communicate his propaganda to a fearful and credulous public. Another famous gimmick of aspirational tyrants is to redefine the threat as circumstances change. So, for example, an official may justify a quarantine initially by pointing out that available resources are inadequate to address an imminent health crisis. The community then responds by redirecting and producing the resources needed. Crisis averted. But the official now has tasted unconstrained power and has perhaps enjoyed the taste. That official may then redefine the threat as an undue risk of infection. Now the emergency must last until adequate treatment arrives. The community then develops a treatment. Crisis averted again. But now the official raises a new alarm: The treatment is not being distributed equally. To oversee the distribution, executive officials must hold onto power a little longer. Meanwhile, officials produce no evidence that their efforts are more efficient or effective than private institutions would be. Indeed, insofar as the goalposts keep moving and the strategic objectives keep changing, officials are not held accountable for their failures to meet reasonable objectives. In this way, an emergency can be artificially extended until the next crisis arrives and the cycle begins anew. Recognizing this danger, the architects of American constitutions followed the jurists of English constitutionalism in placing emergency powers under legislative control. Alabama’s constitution is not unique in this regard. Like other American constitutions, it delegates to the legislature—the people’s branch—the power to declare a quarantine or other emergency. It requires executive officials to exercise any emergency powers delegated to them under law and legislative direction. The legislature, representing the people whose civil liberties are at stake, decides when an emergency is warranted, how long it must last, and how the strategic objectives are to be defined. The legislature’s decisions are laws which then obligate and constrain executive officials as they carry out their duties to avert the crisis. A legislature should never abdicate its responsibility to secure the people’s most fundamental rights. So, it should never confer upon executive officials blanket delegations of power to make war, impose quarantine, or direct states of emergency. Legislatures that have made that mistake should take those powers back. This session, the Alabama legislature has two opportunities to do just that. One pending bill would require executive officials to seek legislative extension of emergency powers after fourteen days. Another would empower the legislature to call itself into session so that it can hold officials accountable throughout the year. Everyone who is not an aspiring tyrant should support both bills. Adam J. MacLeod is Professorial Fellow of the Alabama Policy Institute and Professor of Law at Faulkner University, Jones School of Law. He is a prolific writer and his latest book, The Age of Selfies: Reasoning About Rights When the Stakes Are Personal, is available on Amazon.

Dan Sutter: In case of emergency

Governments have taken numerous extraordinary actions to contain COVID-19. Once the pandemic is over, we can and should revisit the emergency powers laws guiding these policy decisions. How extraordinary have the activities been? Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito described them as “previously unimaginable restrictions on individual liberty.” Confinement of the non-sick through stay-at-home orders and open-ended “nonessential” business closures are unprecedented. A recent scholarly paper contends that COVID has set off an “authoritarian pandemic”. America was founded on the belief that government serves citizens, not the other way around. Our founders created a limited government with the Constitution delegating only specifically enumerated powers to the Federal government. Washington was prohibited from doing anything not specifically authorized. The exercise of new powers without specific authorization should consequently concern proponents of freedom. One concern arises because we do not know precisely when a government may become too strong to remain limited. Beyond this, emergencies have provided the rationale (or excuse) for many expansions of power, as economic historian Robert Higgs documented in Crisis and Leviathan. Liberty-minded scholars acutely fear the threat posed by crises. One of the 20th Century’s greatest economists was Friedrich Hayek. In Law, Legislation, and Liberty he discusses how markets and the common law enable peaceful cooperation and the role for government in a free society. Hayek also proposed protecting freedom by separating the declaration of an emergency from the exercise of these powers. Separation would thwart limit a would-be tyrant wanting to rule by emergency decree. States’ emergency powers laws differ, but Alabama’s illustrates the typical lack of separation. While the governor and state legislature can both declare an emergency, the governor exercises the emergency powers. The law allows a state of emergency for only 60 days, but the governor can just issue a new declaration. I believe Governor Kay Ivey has exercised these powers responsibly, but some governors have abused this dual power. How might we separate these powers? If the governor is going to exercise emergency power, then someone else must declare the emergency. Within the current structure of government, the state legislature and Supreme Court are options. But we could also create a new board to declare public health emergencies. A new board could incorporate relevant expertise. Legislators come from all walks of life and judges are trained in law. A board without independent experts as members would likely be dependent on the state’s experts. Yet since the Alabama Department of Public Health would likely formulate pandemic policies, we would not have full separation. Expertise should not be exclusively from the field of public health. Vanderbilt economist Kip Viscusi has extensively studied risk regulation and observes that government agencies charged with managing one type of risk exhibit excessive focus on “their” risk. The Environmental Protection Agency, for instance, minimizes environmental risks, resulting in enormous expenditures on trivial risks. Tunnel vision becomes worse when regulatory agencies overlap with academic disciplines, as with public health. The vastness of accumulated human knowledge requires that scholarly expertise be extremely narrow. This provides perspective, I think, on COVID-19 policy mistakes. We have focused excessively on the virus, with the CDC even preventing evictions to stem COVID-19. Even other elements of healthcare have been sacrificed, with cancer screenings down over 20 percent and childhood vaccination programs disrupted. And this is before weighing the enormous mental health, economic and educational impacts of pandemic policies. Expertise from other areas of health as well as business and economics should help declare an emergency. COVID-19 is not the last pandemic humanity will face. And because (as I have discussed previously) health and safety are luxury goods, the old ways, namely letting pandemics run their course, will never seem appropriate again. We need a better governance structure for public health emergencies to safeguard our health and freedom in the future. Daniel Sutter is the Charles G. Koch Professor of Economics with the Manuel H. Johnson Center for Political Economy at Troy University and host of Econversations on TrojanVision. The opinions expressed in this column are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of Troy University.

Donald Trump trial video shows vast scope, danger of Capitol riot

Prosecutors unveiled chilling new security video in Donald Trump’s impeachment trial on Wednesday, showing the mob of rioters breaking into the Capitol, smashing windows and doors, and searching menacingly for Vice President Mike Pence and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi as overwhelmed police begged on their radios for help. In the previously unreleased recordings, the House prosecutors displayed gripping scenes of how close the rioters were to the country’s leaders, roaming the halls chanting “Hang Mike Pence,” some equipped with combat gear. Outside, the mob had set up a makeshift gallows. Videos of the siege have been circulating since the day of the riot, but the graphic compilation amounted to a more complete narrative, a moment-by-moment retelling of one of the nation’s most alarming days. In addition to the evident chaos and danger, it offered fresh details on the attackers, scenes of police heroism, and cries of distress. And it showed just how close the country came to a potential breakdown in its seat of democracy as Congress was certifying Trump’s election defeat to Democrat Joe Biden. “They did it because Donald Trump sent them on this mission,” said House prosecutor Stacey Plaskett, the Democratic delegate representing the U.S. Virgin Islands. “His mob broke into the Capitol to hunt them down.” The stunning presentation opened the first full day of arguments in the trial as the prosecutors argued Trump was no “innocent bystander” but rather the “inciter in chief” of the deadly Capitol riot, a president who spent months spreading election lies and building a mob of supporters primed for his call to stop Biden’s victory. Though most of the Senate jurors have already made up their minds on acquittal or conviction, they were riveted and sat silently. Screams from the audio and video filled the Senate chamber. Senators shook their heads, folded their arms, and furrowed their brows. One Republican, James Lankford of Oklahoma, bent his head, a GOP colleague putting his hand on his arm in comfort. “On Jan. 6, President Trump left everyone in this Capitol for dead,” said Rep. Joaquin Castro, D-Texas, a prosecutor. Pence, who had been presiding over a session to certify Biden’s victory over Trump — thus earning Trump’s criticism — is shown being rushed to safety, sheltered in an office with his family just 100 feet from the rioters. Pelosi was evacuated from the complex before the mob prowls her suite of offices, her staff hiding quietly behind closed doors. At one dramatic moment, the video shows police shooting into the crowd through a broken window, killing a San Diego woman, Ashli Babbitt. In another, a police officer is seen being crushed by the mob. Police overwhelmed by the rioters frantically announce “we lost the line” and urge officers to safety. One officer later died. Some senators acknowledged it was the first time they had grasped how perilously close the country came to serious danger. “When you see all the pieces come together, just the total awareness of that, the enormity of this threat, not just to us as people, as lawmakers, but the threat to the institution and what Congress represents, it’s disturbing,” said Republican Sen. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska. “Greatly disturbing.” Trump is the first president to face an impeachment trial after leaving office and the first to be twice impeached. He is charged with incitement of insurrection through fiery words his defense lawyers say are protected by the Constitution’s First Amendment and just figures of speech. The House Democrats showed piles of evidence from the former president himself — hundreds of Trump tweets and comments that culminated in his Jan. 6 rally cry to go to the Capitol and “fight like hell” to overturn his defeat. Trump then did nothing to stem the violence and watched with “glee,” they said, as the mob ransacked the iconic building. “To us, it may have felt like chaos and madness, but there was method to the madness that day,” said Rep. Jamie Raskin, D-Md., the lead prosecutor, who pointed to Trump as the instigator. “And when his mob overran and occupied the Senate and attacked the House and assaulted law enforcement, he watched it on TV like a reality show. He reveled in it.” In one scene, a Capitol Police officer redirects Sen. Mitt Romney, R-Utah, down a hallway to avoid the mob. It was the same officer, Eugene Goodman, who has been praised as a hero for having lured rioters away from the Senate doors. “It tears at your heart and brings tears to your eyes,” Romney said after watching the video. He said he didn’t realize how close he had been to danger. The day’s proceedings unfolded after Tuesday’s emotional start that left the former president fuming when his attorneys delivered a meandering defense and failed to halt the trial on constitutional grounds. Some allies called for yet another shakeup to his legal team. The prosecutors are arguing that Trump’s words were part of “the big lie” — his relentless efforts to sow doubts about the election results, revving up his followers to “stop the steal” even though there was no evidence of substantial fraud. Trump knew very well what would happen when he took to the microphone at the outdoor White House rally that day as Congress gathered to certify Biden’s win, said Rep. Joe Neguse, D-Colo, another impeachment manager. “This was not just a speech,” he said. Security remained extremely tight Wednesday at the Capitol, fenced off and patrolled by National Guard troops. White House press secretary Jen Psaki has said Biden would not be watching the trial. The difficulty facing Trump’s defenders became apparent at the start as they leaned on the process of the trial rather than the substance of the case against him. They said the Constitution doesn’t allow impeachment at this late date after he has left the White House. Even though the Senate rejected that argument in Tuesday’s vote to proceed, the legal issue could resonate with Republicans eager to acquit Trump without being seen as condoning his behavior. Defense

Lawmakers punt on repeal of law about Confederate monuments

Alabama lawmakers on Wednesday delayed action on a proposal to repeal protections for Confederate monuments and instead let cities give the statues to the state archives or another entity for preservation. The House Judiciary Committee sent the bill to a subcommittee for study. It is unclear when the bill would return for a vote. The bill by Democratic Rep. Juandalynn Givan of Birmingham would repeal the 2017 Alabama Memorial Preservation Act which forbids taking down longstanding monuments. Givan said her proposal would allow local governments to donate unwanted historic statues and monuments to the state archives or another entity for preservation. The 2017 law, which was approved as some cities began taking down Confederate monuments, forbids the removal or alteration of monuments more than 40 years old. Violations carry a $25,000 fine. Some cities have opted to take down Confederate monuments and just pay the $25,000 fine. “People want to have the authority to move these monuments without being taxed $25,000,” Givan said after the meeting. Democratic Rep. Merika Coleman of Pleasant Grove said Givan’s bill would put the monuments in a “spot where they actually could be preserved and not destroyed.” A Republican lawmaker is seeking to strengthen the law and increase the penalty on violators. Rep. Mike Holmes of Wetumpka filed a bill that would increase the fine from a flat $25,000 to $10,000 a day. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

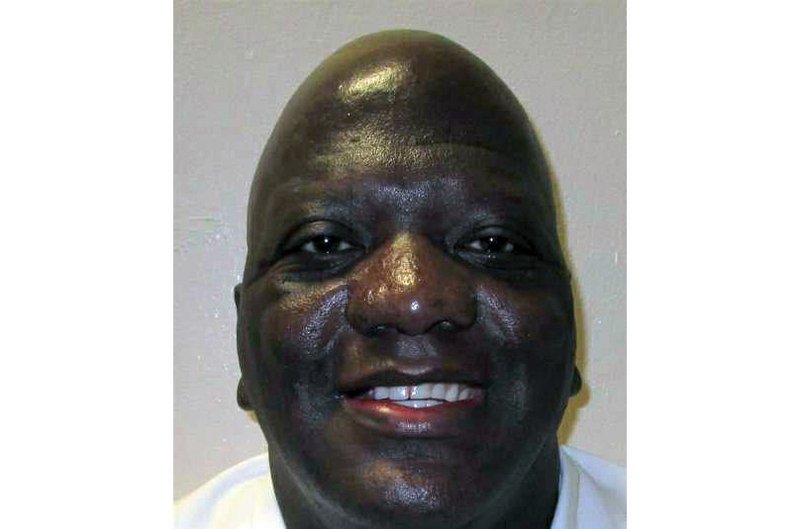

Alabama set to carry out its first execution during pandemic

Alabama is preparing to execute an inmate by lethal injection in what would be the state’s first death sentence carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic. Willie B. Smith III, 51, is scheduled to be put to death Thursday at a south Alabama prison for the 1991 shotgun slaying of Sharma Ruth Johnson. It would be the first execution carried out by any state in 2021, although there have been federal executions, according to a list maintained by the Death Penalty Information Center. U.S. District Judge Austin Huffaker, Jr. on Tuesday denied Smith’s lawyers request for a stay. The Alabama Supreme Court ruled the execution could go forward with precautions. Smith’s attorneys have sought a stay arguing that the pandemic and the prohibition on in-person prison visits had made it difficult for them to adequately represent him. They said Smith has been unable to receive the number of in-person visits from attorneys, friends, and a pastor that death row inmates normally do before their date in the execution chamber. The prison system said Smith could have contact visitation during the week preceding his execution. Attorneys also argued the execution would be a super-spreader event. Some COVID-19 cases have been linked to recent federal executions. The Alabama attorney general’s office wrote in court filings that the state is no longer under a stay-at-home order and said carrying out executions is one of the functions of state government. “The State is open, and its agencies are expected to function. One of the State’s functions is to ensure that justice is carried out in a timely fashion by performing executions of those inmates on death row who have exhausted their appeals,” the Alabama attorney general’s office wrote. The Department of Corrections has changed some procedures in the face of the pandemic. The prison system is limiting media witnesses to the execution to a single reporter, a representative from The Associated Press. Prosecutors said Smith abducted Johnson at gunpoint in October 1991 as she waited to use an ATM in Birmingham, forced her into the trunk of a car, and withdrew $80 using her bank card. Prosecutors said he then took her to a cemetery where he shot her in the back of the head and later returned to set the car on fire. A jury convicted Smith in 1992 in the death of Johnson, who was the sister of a Birmingham police detective. Appellate courts rejected Smith’s claims on appeal, including that his lawyers provided ineffective assistance at trial and that he should not be executed because he is intellectually disabled. Court records indicate a defense team expert estimated his IQ at 64 while a prosecution expert pegged it at 72. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Alabama Senate committee advances lottery, casino bill

A lottery and casino bill cleared its first hurdle in the Alabama Legislature as supporters push to get the issue of gambling before voters for the first time since 1999. The Senate Tourism and Marketing Committee unanimously voted to advance the legislation to the full Alabama Senate. Sponsor Sen. Del Marsh said he anticipates the Senate will discuss the bill Thursday, but he will not seek a vote until lawmakers return from a planned weeklong break. “I firmly believe the people of Alabama want to address this issue once and for all,” Marsh said during the committee voting. The bill proposes a state lottery as well as five casinos offering table games, sports betting and slot machines. The casinos would be located at four existing dog tracks plus a fifth site in north Alabama that would be run by the Poarch Band of Creek Indians, the state’s only federally recognized, Native American tribe. The proposal also would encourage the governor to negotiate with the Poarch Band for a compact involving their three other sites which currently have electronic bingo machines. The proposal would have to be approved by a three-fifths majority of each chamber of the Alabama Legislature and then a majority of voters in a statewide vote. The bill will need 21 yes votes to clear the Alabama Senate. Sen. Jabo Waggoner, R-Vestavia Hills, said he was undecided on the bill because of the casino portion. Waggoner said he believes most voters support a lottery, but he was uncertain about allowing casinos in the state. “I’ve got to think about casinos a long time, but I think lottery would be an easy sale to the Legislature and to the public. There is going to be debate on opening up Alabama to casinos,” Waggoner said. The Legislative Services Agency estimated the lottery would generate $194-$279 million annually for college scholarships awarded on a mix of need, merit, and workforce needs in the state. The agency estimated the casinos would generate $260-$393 million annually from the 20% tax on gaming revenues as authorized by this amendment. Marsh is proposing to use casino revenue to help expand broadband access in the state as well as to fund mental and rural health services. Alabamians last voted on gambling in 1999 when they defeated a lottery proposed by then-Gov. Don Siegelman. Gambling bills introduced since 1999 have fallen short under a mix of conservative opposition to gambling as a revenue source and a turf war over which entities could offer casino games or electronic bingo machines, which resemble slot machines. Marsh said the location the tribe would operate would be located in either Jackson or DeKalb counties. The other four would be at VictoryLand dog track in Macon County, Greenetrack in Green County, the racecourse in Birmingham, and the racecourse in Mobile, which is owned by the Poarch Band. Sharon Wheeler, a lobbyist representing the Whitehall Entertainment Center, a smaller electronic bingo operator in Lowndes County, said it was unfair to exclude the smaller site that provides jobs in one of the most impoverished areas of the state while allowing cities and north Alabama to have casinos and the jobs they create. Sen. Malika Sanders Fortier, who represents the area, sent a letter to the committee asking her colleagues to include the site. The bill was approved by committee with little discussion, but Marsh said he expects lawmakers will discuss the bill during the break. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.