Judges maintain order for Alabama to draw new districts

A three-judge panel on Thursday refused to stay its decision that effectively orders Alabama to draw new congressional districts before the 2022 elections and to create a second district of which Black voters are a sizeable portion of the population. The panel denied Alabama’s request to put a preliminary injunction on hold as the state appeals the decision. In a sometimes strongly worded ruling, the judges reiterated findings they believe show the current map likely violates the Voting Rights Act and that demographic shifts merit the creation of a second district — instead of this one — with a substantial number of minority voters. The judges wrote they are “aware that the preliminary injunction is consequential” but said it was necessary. “We discern no basis for a finding that this case is the extraordinary case in which we must allow an election to proceed under a map that we have determined — on the basis of a substantial evidentiary record — very likely violates the Voting Rights Act,” the judges wrote. A spokesman said the Alabama attorney general’s office did not have a comment on the ruling. Alabama is currently represented by one Black Democrat elected from the state’s only majority-Black district and white Republicans elected from heavily white districts. About 27% of the state’s population is Black. The three-judge panel said it was a “red herring” for the state to argue the current districts are lawful because they resemble long-used districts. “The argument also ignores the obvious reality that as maps age, demographic changes may eventually turn a lawful map into an unlawful map,” the judges wrote. Alabama’s Black population rose from 25.26% of the population in the 1990 census to 27.1% of the population in the 2020 census. At the same time, the white population dropped from 73.65% of the population in the 1990 census to 63.12% of the population in 2020. The three judges that issued the ruling consisted of one judge appointed by former President Bill Clinton — Senior U.S. Circuit Judge Stanley Marcus and two judges appointed by former President Donald Trump — U.S. District Judge Anna Manasco and U.S. District Judge Terry Moorer. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

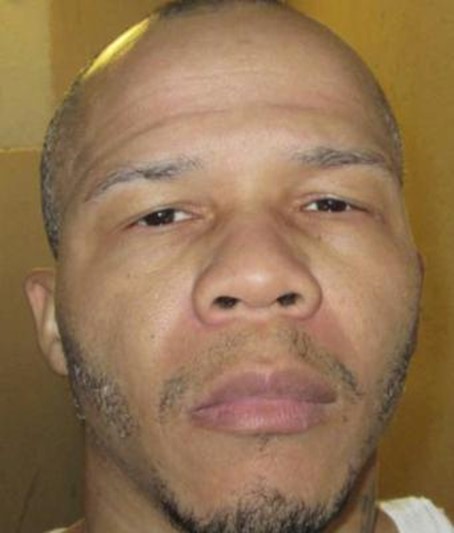

Matthew Reeves executed for 1996 killing after Supreme Court clears way

Alabama executed an inmate by lethal injection for a 1996 murder on Thursday after a divided U.S. Supreme Court sided with the state and rejected defense claims the man had an intellectual disability that cost him a chance to choose a less “torturous,” yet untried, execution method. Matthew Reeves, 43, was put to death at Holman Prison after the court lifted a lower court order that had prevented corrections workers from executing the prisoner. He was pronounced dead at 9:24 p.m. CST, state Attorney General Steve Marshall said in a statement. Reeves was convicted of killing Willie Johnson Jr., a driver who gave him a ride in 1996. Evidence showed Reeves went to a party afterward and celebrated the killing. The inmate had no last words. After craning his neck to look around a few times, Reeves grimaced and looked at his left arm toward an intravenous line. With his eyes closed and mouth slightly agape, Reeves’ abdomen moved repeatedly before he grew still.ADVERTISEMENT Gov. Kay Ivey, in a statement, said Johnson was “a good Samaritan lending a helping hand” who was brutally murdered. Reeves’ death sentence “is fair, and tonight, justice was rightfully served,” she added. Prison officials said some of Johnson’s family witnessed the execution. In a written statement, they said: “After 26 years justice (has) finally been served. Our family can now have some closure.” Reeves was convicted of capital murder for the slaying of Johnson, who died from a shotgun blast to the neck during a robbery in Selma on Nov. 27, 1996. He was killed after picking up Reeves and others on the side of a rural highway. After the dying man was robbed of $360, Reeves, then 18, went to a party where he danced and mimicked Johnson’s death convulsions, authorities said. A witness said Reeves’ hands were still stained with blood at the celebration, a court ruling said. While courts have upheld Reeves’ conviction, the last-minute fight by his lawyers seeking to stop the execution involved his intellect, his rights under federal disability law, and how the state planned to kill him. The Supreme Court on Thursday evening tossed out a decision by the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, which had ruled Wednesday that a district judge didn’t abuse his discretion in ruling that the state couldn’t execute Reeves by any method other than nitrogen hypoxia, which has never been used. Reeves’ attorneys criticized the Supreme Court’s failure to explain its decision to let the execution proceed. “The immense authority of the Supreme Court should be used to protect its citizens, not to strip them of their rights without explanation,” they said. In 2018, Alabama death row inmates had a chance to sign a form choosing either lethal injection or nitrogen hypoxia as an execution method after legislators approved the use of nitrogen. But Reeves was among the inmates who didn’t fill out the form stating a preference. Suing under the American With Disabilities Act, Reeves claimed he had intellectual disabilities that prevented him from understanding the form offering him the chance to choose nitrogen hypoxia — a method never used in the U.S. — over lethal injection, which the inmate’s lawyers called “torturous.” Reeves also claimed the state failed to help him understand the form. But the state argued he wasn’t so disabled that he couldn’t understand the choice. It was a divided court that let the execution proceed. Justice Amy Coney Barrett said she would deny the state’s request, while Justice Stephen Breyer, who just announced his retirement, and Justice Sonia Sotomayor joined with Justice Elena Kagan in a dissent that said the execution shouldn’t occur. The state had previously asked the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals to lift a lower court injunction and allow the execution, but the panel on Wednesday had refused. Alabama then appealed, sending the case to the nation’s highest court. Alabama switched from the electric chair to lethal injection after 2002, and in 2018 legislators approved the use of another method, nitrogen hypoxia, amid defense challenges to injections and shortages of chemicals needed for the procedure. The new method would cause death by replacing oxygen that the inmate breathes with nitrogen. A poor reader and intellectually disabled, Reeves wasn’t capable of making such a decision without assistance that should have been provided under the American With Disabilities Act, his lawyers argued. A prison worker who gave Reeves a form didn’t offer aid to help him understand, they said. With Reeves contending he would have chosen nitrogen hypoxia over a “torturous” lethal injection had he comprehended the form, the defense filed suit asking a court to halt the lethal injection. U.S. District Judge R. Austin Huffaker, Jr. blocked execution plans, ruling that Reeves had a good chance of winning the claim under the disabilities law. A defense expert concluded Reeves had a first-grade reading level and the language competency of someone as young as 4, but the state disagreed that Reeves had a disability that would prevent him from understanding his options. An Alabama inmate who was put to death by lethal injection last year, Willie B. Smith, unsuccessfully raised claims about being intellectually unable to make the choice for nitrogen hypoxia. Stavros Lambrinidis, the European Union ambassador to the U.S., had sent a letter both condemning Johnson’s killing and asking the governor Ivey to block the execution.

Police chief Mike Jones quits amid questions over ticketing

The police chief in a small Alabama town that received about half its municipal revenue from fines and forfeitures linked to aggressive traffic enforcement resigned following a report about the practice. Mike Jones, chief of police in the Jefferson County town of Brookside, quit following a recent story by AL.com that said he turned the department into a traffic trap that by 2020 relied on income from ticketing people for minor and questionable offenses as they drive by on Interstate 22. A statement from Debbie Keedy, who works as clerk of the town of roughly 1,250 people, said Jones resigned on Tuesday. “Since this involves a personnel matter, the town has no further comment,” it said. County officials were critical of the town’s practices, and Republican and Democratic officials discussed ways to rein in a system that sometimes is referred to as policing for profit. Jones was hired in 2018. Brookside, once a mining community, under Jones built a police force of 10 or more full and part-time officers with 10 dark vehicles that patrol I-22. The town has no traffic lights and only one store, but in 2020 collected $487 in fines and forfeitures for every man, woman and child. Income from fines and forfeitures rose 640% in two years, and by 2020 the total came to $610,000, or 49% of the town’s $1.2 million budget. The Institute for Justice, a nonprofit, public interest law firm based in Virginia, contends that cities which rely on fines and fees for more than 10% of their revenue deserve scrutiny for what it calls “taxation by citation,” AL.com reported. In Brookside, on days when municipal court is held, so many people show up for tickets that officers have to direct traffic. The city faces at least five federal lawsuits for its policing, and officials including Lt. Gov. Will Ainsworth sought investigations by the Justice Department and the state attorney general and audits. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Vaccine mandate to kick in for first wave of health workers

Health care workers in about half the states face a Thursday deadline to get their first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine under a Biden administration mandate that will be rolled out across the rest of the country in the coming weeks. While the requirement is welcomed by some, others fear it will worsen already serious staff shortages if employees quit rather than comply. And in some Republican-led states that have taken a stand against vaccine mandates, hospitals, and nursing homes could find themselves caught between conflicting state and federal demands. “We would like to see staff vaccinated. We think that it’s the safest option for residents, which is our biggest concern,” said Marjorie Moore, executive director of VOYCE, a St. Louis County, Missouri, nonprofit that works on behalf of nursing home residents. “But not having staff is also a really big concern because the neglect that happens as a result of that is severe and very scary.” The mandate affects a wide swath of the health care industry, covering doctors, nurses, technicians, aides, and even volunteers at hospitals, nursing homes, home health agencies, and other providers that participate in the federal Medicare or Medicaid programs. It comes as many places are stretched thin by the omicron surge, which is putting record numbers of people in the hospital with COVID-19 while sickening many health workers. Nationwide, about 81% of nursing home staff members already were fully vaccinated as of earlier this month, ranging from a high of 98% in Rhode Island to a low of 67% in Missouri, according to the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The data is unclear about the vaccination levels in hospitals and other health care sites. The mandate ultimately will cover 10.4 million health care workers at 76,000 facilities. It is taking effect first in jurisdictions that didn’t challenge the requirement in court. Those include some of the biggest states, with some of the largest populations of senior citizens, among them: California, Florida, New York, and Pennsylvania. “There absolutely have been employee resignations because of vaccination requirements,” said Catherine Barbieri, a Philadelphia attorney at Fox Rothschild who represents health care providers. But “I think it’s relatively small.” At Wilson Medical Center in rural Neodesha, Kansas, three of the roughly 180 employees are quitting, and several others have sought exemptions from the vaccine mandate, said hospital spokeswoman Janice Reese. “We are very fortunate that that is all we are losing,” she said, noting that the hospital was not in favor of the mandate. “We didn’t feel like it was our place to actually try to tell a person what they had to do.” Reese said the vaccine requirement could also make it more difficult for the hospital to fill vacancies. In Florida, medical centers find themselves caught between dueling federal and state vaccination policies. They could lose federal funding for not adhering to the Biden administration mandate but could get hit with fines for running afoul of state law. Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican who has waged a legal campaign against coronavirus mandates, last year signed legislation that forces businesses with vaccine requirements to let workers opt-out for medical reasons, religious beliefs, immunity from a previous infection, regular testing, or an agreement to wear protective gear. Businesses that fail to comply can be fined $10,000 to $50,000 per violation. Asked if the state would pursue fines against hospitals that enforce the federal mandate, a spokeswoman for the Florida attorney general said all employee complaints “will be thoroughly reviewed by our office.” Some states already have their own vaccine requirements for health care workers. In California, for example, they have been required to be fully vaccinated since September 30 and must get a booster by February 1. The federal mandate is “better late than never,” said Sal Rosselli, president of the National Union of Healthcare Workers, which represents about 15,000 people in California. “But if it happened sooner, we wouldn’t have gone through the surge, and a lot more people would be alive today.” The government said it will begin enforcing the first-dose vaccine requirement on February 14 in two dozen other states where injunctions were lifted when the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the mandate two weeks ago. The requirement will kick in on February 22 in Texas, which had filed suit separately. In Missouri, one nursing home served notice this week that it intends to take advantage of a state rule that allows facilities to close for up to two years if they are short-staffed because of the vaccine requirement. “Obviously, we are proponents of vaccines,” said Lisa Cox, a spokeswoman for the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services. But “throughout all of this, we knew that mandating it would be a negative impact really on our health care system … just because of crippling staffing levels.” Cox identified the facility that was closing as Cedarcrest Manor in the eastern Missouri city of Washington. She said there are just 42 patients in the 177-bed facility amid the staffing shortages. A woman who answered the phone at the facility took a message but couldn’t immediately comment. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services ultimately could cut off funding to places that fail to comply with the mandate. But it plans to begin enforcement with encouragement rather than a heavy hand. CMS guidance documents indicate it will grant leniency to places that have at least 80% compliance and an improvement plan in place, and it will seek to prod others. “The overarching goal is to get providers over that finish line and not be cutting off federal dollars,” said MaryBeth Musumeci, a Medicaid expert with the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation. The states affected on Thursday are California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin, along with the District of Columbia and U.S. territories. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Roy Moore gives combative testimony in defamation case

A combative Roy Moore took the witness stand Thursday in a defamation case against him, insisting he did not know a woman who says he sexually molested her when she was 14. Moore was called to testify by attorneys for Leigh Corfman in a trial dealing with dueling defamation lawsuits they filed against each other in the wake of a sexual misconduct allegation that rocked the 2017 U.S. Senate race in Alabama. Corfman says the former Alabama judge and failed Senate candidate defamed her when he denied her accusations as false and malicious. Moore countersued. “I never met that woman,” Moore said loudly, pointing at Corfman as she sat with her attorneys. The outburst followed an emotional moment earlier in the trial when Corfman testified that Moore knows what he did to her. Corfman said she met Moore in 1979 when she was 14 and he was in his 30s. She described how he touched her over her underwear after bringing her to his home. At one point Corfman stared from the witness stand at Moore, who stared back at her. “It did happen, and he knows that it happened,” Corfman testified Tuesday. She said his denials damaged her reputation. The allegations overshadowed the conservative Republican during the 2017 campaign when Corfman shared her story with a reporter from The Washington Post. Moore ultimately fell in a stunning red state defeat to Doug Jones, the first Alabama Democrat elected to the Senate in 25 years. Republican Tommy Tuberville defeated Jones in the next election. The presiding judge had to gently chide Moore multiple times Thursday to answer questions as they were asked. Asked if he was afraid 2017 voters would view the conduct as inappropriate, Moore said: “The only thing inappropriate in this case is the testimony that I knew her and did anything to her.” Corfman’s attorneys earlier in the day presented the testimony of four women who said Moore asked them out or dated them when they were teens. None accused him of misconduct Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Supreme Court considers Alabama’s bid to allow execution of Matthew Reeves

The U.S. Supreme Court considered Thursday whether to let Alabama execute a death row inmate who claims an intellectual disability combined with the state’s inattention cost him a chance to avoid lethal injection and choose a less “torturous,” yet untried, method. The Alabama attorney general’s office asked the justices to lift a lower court order that blocked prison workers from putting to death Matthew Reeves, who was convicted of killing a driver who gave him a ride. He celebrated after the killing at a party with blood still on his hands, evidence showed. The defense argued that the state, in asking the court to vacate an earlier ruling so it could execute Reeves, was improperly trying to challenge a decision it had lost repeatedly in lower courts. The state said it was preparing to execute Reeves, 43, by lethal injection at Holman Prison in case the court allowed it to proceed as scheduled at 6 p.m. CST, but the execution time passed without any word from the court. Reeves had visits and phone calls with his mother and sister during the day and was moved into a holding cell near the death chamber as he awaited the court decision, said deputy commissioner Jeffery Williams. Reeves, who also spoke with his lawyer by phone, declined a last meal, he said. The state previously asked the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals to lift a lower court injunction and allow the execution, but the panel on Wednesday refused and said a judge didn’t abuse his discretion in ruling that the state couldn’t execute Reeves by any method other than nitrogen hypoxia, which has never been used. Alabama appealed that decision, sending the case to the Supreme Court. Reeves was sentenced to die for the murder of Willie Johnson, who was killed by a shotgun blast to the neck during a robbery in Selma on Nov. 27, 1996, after picking up Reeves and others on the side of a rural highway. After the dying man was robbed of $360, Reeves, then 18, went to a party where he danced and mimicked Johnson’s death convulsions, authorities said. A witness said Reeves’ hands were still stained with blood at the celebration, a court ruling said, and he bragged about getting a “teardrop” tattoo to signify that he’d killed someone. Stavros Lambrinidis, the European Union ambassador to the U.S., sent a letter both condemning Johnson’s killing and asking Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey to block the execution because of Reeves’ intellectual disability claim. Ivey also has received a clemency bid from Reeves’ attorneys and will consider all such requests, an aide said. While courts have upheld Reeves’ conviction, the last-minute fight to stop the execution involved his intellect, his rights under federal disability law, and how the state planned to kill him. Alabama switched from the electric chair to lethal injection after 2002, and in 2018 legislators approved the use of another method, nitrogen hypoxia, amid defense challenges to injections and shortages of chemicals needed for the procedure. The new hypoxia method, which hasn’t been used in the U.S., would cause death by replacing oxygen that the inmate breathes with nitrogen. Alabama inmates had a chance to sign a form choosing either lethal injection or nitrogen hypoxia as an execution method in 2018 after legislators approved the use of nitrogen. But Reeves was among the inmates who didn’t fill out the form stating a preference. A poor reader, Reeves is intellectually disabled and wasn’t capable of making such a decision without assistance that should have been provided under the Americans With Disabilities Act, his lawyers argued. A prison worker who gave Reeves a form didn’t offer aid to help him understand, they said. With Reeves contending he would have chosen nitrogen hypoxia over a “torturous” lethal injection had he comprehended the form, the defense filed suit asking a court to halt the lethal injection. U.S. District Judge R. Austin Huffaker, Jr. blocked execution plans, ruling that Reeves had a good chance of winning the claim under the disabilities law. A defense expert concluded Reeves reads at a first-grade level and has the language competency of someone as young as 4, but the state disagrees that Reeves has a disability that would prevent him from understanding his options. The inmate was able to read and signed other forms through the years, it argued, and officials had no obligation under state law to help him pick a method. Alabama has said it plans to have a system for the new execution method ready by the end of April, court documents show, but the state argued against delaying Reeves’ execution. Any postponement is the fault of the state given how long it has taken to implement the new system, the 11th Circuit ruled. An Alabama inmate who was put to death by lethal injection last year, Willie B. Smith, unsuccessfully raised claims about being intellectually unable to make the choice for nitrogen hypoxia. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.