Adeline Von Drehle: SCOTUS decision may limit more than just the EPA

The Supreme Court wrapped up its history-making term last week with a shot across the bow at government regulatory agencies. One of its two final rulings, West Virginia v. EPA, saw the court rule 6-3 along ideological lines that the Clean Air Act does not give the Environmental Protection Agency broad authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from power plants. Ruling for the state of West Virginia, the conservative justices struck down EPA standards designed to fight climate change by reshaping electricity grids. Such standards qualify as “major questions,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts in his majority opinion, requiring explicit authorization by Congress. Much of the interest in the case comes from those who fear the United States will no longer be able to meet its climate change commitments. In her dissent, Justice Elena Kagan wrote that the court was stripping the EPA of the power Congress gave it to respond to “the most pressing environmental challenge of our time.” President Joe Biden, in a statement issued at the White House Thursday, described the ruling as “another devastating decision that aims to take our country backwards.” The opinion completed a term in which an already conservative court lurched further to the right, striking down Roe v. Wade, expanding gun rights, embracing religious expression – and now cracking down on the so-called “administrative state.” Careful vetting of three justices appointed by former president Donald J. Trump by the conservative Federalist Society produced results long dreamed of by self-styled “originalist” theorists. Laurence Tribe, University Professor Emeritus of Constitutional Law at Harvard, told RealClearPolitics that the current court “is going rogue and seems almost drunk with the power acquired with its stacking by Trump and his three new Justices.” West Virginia’s victory may be only an opening salvo in a conservative war against the active federal government called into existence during the Great Depression. If every significant new challenge requires new Congressional authorization to act – as the Roberts opinion suggests – critics fear the executive branch could become just as gridlocked as the legislative branch. Roberts pointed in this direction by describing the dispute at hand as a “major questions case.” The major questions doctrine requires that agencies have explicit statutory authorization from Congress to make “decisions of vast economic and political significance.” The court “typically greet[s] assertions of extravagant statutory power over the national economy with skepticism,” Roberts wrote. To overcome that skepticism, “the Government must – under the major questions doctrine – point to clear congressional authorization to regulate in that manner.” The major questions doctrine plays an important role in administrative law because it allows Congress to find, in theory, a workable space between an unconstitutional delegation of power – a violation of Article I Section I of the Constitution, which states that “All legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States” – and a complete ban on delegation that would leave an already inactive Congress swamped with day-to-day responsibility for government agencies. One traditional view holds that Congress sets up a target, but agencies decide how to hit the target. In the West Virginia case, the EPA’s target was the reduction of carbon emissions. The EPA aimed to hit that target by requiring a gradual transition to green energy. New York University Law Professor Roderick M. Hills explained to RCP that the Roberts ruling suggests that Congressional legislation “doesn’t only contain the target,” it also regulates the means that the agency can use. So, if the agency chooses a novel or controversial method of achieving the congressionally specified goal, it might be going outside the statute. The issue with a doctrine that says an agency cannot do anything outside its statutory authorization, Hills said, “is that when a new problem arises, agencies are helpless. And the whole point of creating an agency is to respond to unforeseen circumstances.” The modern administrative state was born during the New Deal Era, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt sought a way to respond to the economic crisis quickly, bypassing bureaucratic red tape – or even congressional intent. There is always a trade-off, Hills said, between “lots and lots of democratic deliberation, and fast action. It’s like Elvis Presley said, a little less conversation, a little more action.” If the court requires agencies to go to Congress each time they seek new ways to address issues of major economic and political significance, Hills asserts, “We’re never going to do anything to respond to new problems because Congress is mired in gridlock.” He has a point, given that Congress currently has a 4% success rate of turning bills into laws. Some would argue that the slow pace of the congressional process is not only desirable, but constitutionally obligatory. Others think it’s unrealistic and, in some ways, undemocratic. Since the 1819 landmark decision McCulloch v. Maryland, the court has held that “the modern administrative state is constitutional,” Tribe told RCP. That case affirmed that Congress can turn over responsibility for detail-oriented action to freestanding government agencies. But it is unclear what is a detail and what is a significant, or “major,” issue. “The Constitution doesn’t say anything about major questions,” Hills told RCP. “If you think the most valuable thing is to have every issue passed upon by elected representatives, [the court] is right. If you think the most valuable thing, or at least an equally valuable thing, is to actually have policy that’s responsive to problems, then [the court] is wrong.” That said, for those who disagree with the EPA ruling, there’s a straightforward remedy that isn’t necessarily available when it comes to the court’s recent gun control decisions or the religious freedom cases. That’s because EPA’s regulatory overreach on climate change – at least according to the Supreme Court – did not run afoul of the pesky First Amendment or Second Amendment. In that sense, West Virginia v. EPA has something in common with the Dobbs decision: namely, the obvious possibility of a legislative fix. In

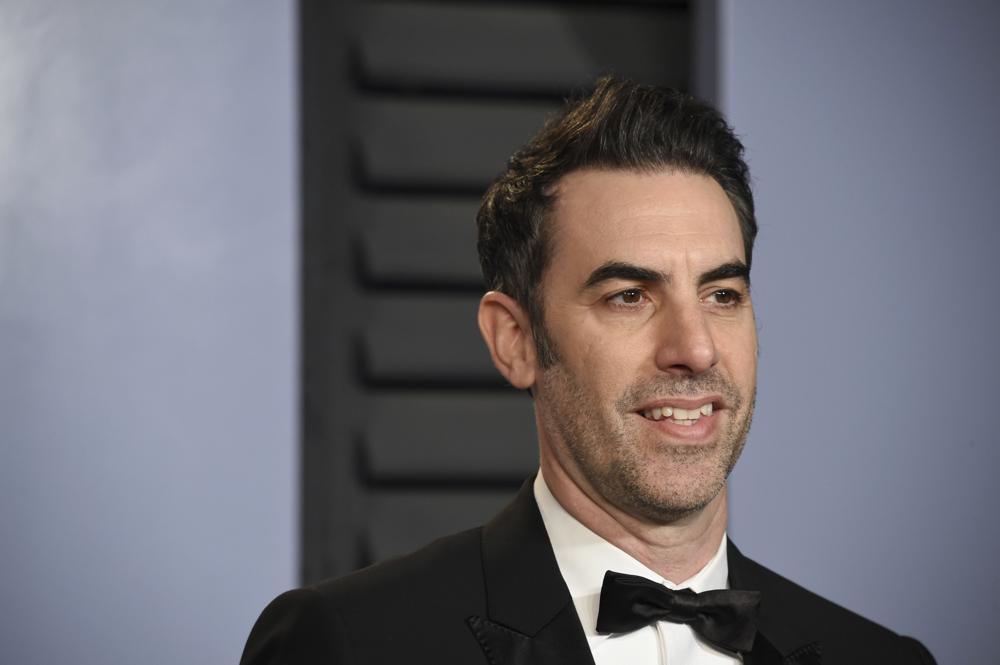

Roy Moore’s defamation suit against Sacha Baron Cohen rejected

An appeals court on Thursday rejected a $95 million defamation lawsuit against comedian Sacha Baron Cohen filed by former Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Roy Moore, who said he was tricked into a television appearance that lampooned sexual misconduct accusations against him. The 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Manhattan, upholding a lower court’s ruling in favor of Baron Cohen, said Moore signed a disclosure agreement that prohibited any legal claims over the appearance. The three judges also found it was “clearly comedy” when Baron Cohen demonstrated a so-called pedophile detector that beeped when it got near Moore and no viewer would think the comedian was making factual allegations against Moore. The lawsuit centered on Moore’s unwitting appearance on the comic’s “Who is America?” show. The segment ran after Moore faced misconduct accusations during Alabama’s 2017 U.S. Senate race that he had pursued sexual and romantic relationships with teens when he was a man in his 30s. He denied the allegations. Moore, a Republican known for his hardline stances opposing same-sex marriage and supporting the public display of Ten Commandments, had been told he was receiving an award for supporting Israel. But in the segment, Baron Cohen appeared as faux counterterrorism instructor “Col. Erran Morad” discussing bogus military technology, including the supposed pedophile detector. The fake device beeped repeatedly as it got near Moore, who sat stone-faced. “Baron Cohen may have implied (despite his in-character disclaimers of any belief that Judge Moore was a pedophile) that he believed Judge Moore’s accusers, but he did not imply the existence of any independent factual basis for that belief besides the obviously farcical pedophile detecting ‘device,’ which no reasonable person could believe to be an actual, functioning piece of technology,” the court wrote in the unsigned summary order. Moore and his wife, Kayla, sued, arguing that the segment defamed Moore and caused them emotional distress. The couple claimed the waiver Moore signed was unenforceable because it was obtained under a false representation. The appellate court noted that it was indeed a ruse that got Moore to appear on the show but Moore signed a binding release waiving all legal claims. The accusations against Moore contributed to his loss to Democrat Doug Jones, the first Democrat to represent Alabama in the Senate in a quarter-century. The seat returned to Republican control when Jones lost the following election to Sen. Tommy Tuberville, a former college football coach. Baron Cohen has for years lured unwitting politicians into awkward interviews. He has faced past lawsuits over similar pranks, but those were also tossed out because the individuals had signed releases. Moore and his wife indicated they will appeal. “For far too long the American people have been subjected to the antics of Sasha Baron Cohen. His pusillanimous and fraudulent conduct must be stopped. We will appeal,” the couple said in a statement texted to The Associated Press. Republished with the permission of The Associated Press.