Auburn University fires Bryan Harsin as football coach

The Auburn University football team went into halftime on Saturday trailing the Arkansas Razorbacks in a tight game. The visiting Razorbacks came out at halftime and completely dominated Auburn. Auburn got two late scores to make the 41 to 27 game closer than it appeared, but Auburn fans had already begun leaving the stadium by the thousands. New University President Chris Roberts and the decision makers at Auburn had seen enough, and on Monday, the decision was announced that head football coach Bryan Harsin was fired. Last year’s team finished 6 and 6 and went to a bowl game in Birmingham. After losses to Penn State, Ole Miss, LSU, and Arkansas and poor play in victories over Mercer, San Jose State, and Missouri that were often more disturbing for Auburn fans than the losses, it was apparent that year two of the Harsin era was not going to even approach the low bar set in 2020 that resulted in an attempted coup and formal investigation of the football program by the outgoing administration. Athletics Director Allen Greene, who hired Harsin, left in August when it was apparent that his contract was not going to be renewed. On Monday, Auburn announced that new AD John Cohen will make $1.5 million a year. The first act of his tenure was firing Harsin and beginning the search for Auburn’s next football coach. Harsin was hired by Greene just 22 months ago over booster’s objections, who preferred former defensive coordinator Kevin Steele. The fans and boosters never really rallied behind Harsin, the former Boise State Coach; but a losing record, two horrid recruiting classes, spats with assistant coaches, and an exodus of talented players out of the transfer portal meant that Harsin never gave the Auburn faithful much to cheer about. Roberts and the leadership made the decision that the program could not realistically let Harsin coach out his six-year $31.5 million contract so it was better to end the Harsin era now rather than waiting to the end of November to begin the coaching search. “Auburn University has decided to make a change in the leadership of the Auburn University football program,” the University said in a statement on Monday. “President Roberts made the decision after a thorough review and evaluation of all aspects of the football program. Auburn will begin an immediate search for a coach that will return the Auburn program to a place where it is consistently competing at the highest levels and representing the winning tradition that is Auburn football.” As of press time, the University has not announced who will be the interim coach. To connect with the author of this story, or to comment, email brandonmreporter@gmail.com.

William S. Smith: Nonprofit hospitals need to get back to charity work

Nonprofit hospitals are among the most important safety net institutions in the United States. Thousands of times each day, they treat low-income patients without insurance at no cost to the patient. In 1992, in order to support this charity work, the federal government created the 340B drug discount program for nonprofit hospitals and clinics. The 340B program allows these nonprofits to buy drugs at very steep discounts compared with other customers, providing substantial revenues for the bottom lines of hospitals. Consider an example of how this program boosts hospitals’ revenue. Suppose a hospital could purchase an oncology drug for $25,000, a 75% discount from the drug’s market price (and a discount level not uncommon in the 340B program). However, if the hospital dispensed that drug to a patient with good insurance coverage, they may be able to bill that insurance company at $100,000, allowing the hospital to pocket a profit of $75,000 on a single prescription. One economist recently concluded that the 340B program had boosted nonprofit hospital revenues by $40 billion in a single year, 2019. When they created the 340B program, Congress thought that this additional revenue should be devoted to charity care programs. Unfortunately, at many nonprofit hospitals, charity care has been declining at the same time that revenue from the 340B program have been exploding. A recent Wall Street Journal analysis concluded that nonprofit hospitals that secure billions through the 340B program provide less charity care than for-profit hospitals that receive zero revenue from the 340B program. “These charitable organizations, which comprise the majority of hospitals in the U.S., wrote off in aggregate 2.3% of their patient revenue on financial aid for patients’ medical bills,” write Anna Wilde Mathews, Tom McGinty, and Melanie Evans in an investigative report for the Wall Street Journal. “Their for-profit competitors … wrote off 3.4%, the Journal found in an analysis of the most recent annual reports hospitals file with the federal government.” Louisiana’s Ochsner Health system drew special attention from the Journal for dedicating among the skimpiest share of patient revenue to charity care, less than 1%. Elsewhere, it was reported in February that Our Lady of the Lake and LCMC Health had committed a quarter of a billion dollars to Louisiana State University, the largest outside investment in university history. That’s all well and good until you realize that according to their June 2020-June 2021 Schedule H filing, Our Lady of the Lake contributes 0.5%, or $7.5 million – from a total of $1.54 billion – of its patient revenues to charity care. Did the hospital’s 340B funds pay for a huge investment in LSU’s research? It is true that many nonprofit hospitals have challenges with low reimbursements from the Medicaid program, labor shortages, and other difficulties. Therefore, Congress could do one simple thing that may improve the 340B program and increase patient access to charity care: transparency. Congress should require nonprofit hospitals and clinics to publicly report the amount of revenue that they are securing through the 340B program, and they also should be required to report, under a uniform definition of charity care, the level of free or discounted care they are providing. That way, policymakers could see if 340B revenues are largely being devoted to charity care, which was the intention of Congress, or if 340B funds are being diverted to executive compensation, hospital acquisitions, or other expenses. Sadly, many nonprofit hospitals have lost their way and have gotten away from the mission that animated their creation: helping those in dire economic need afford healthcare. That needs to change. William S. Smith, Ph.D., is a Senior Fellow and Director of the Life Sciences Initiative at Pioneer Institute in Boston.

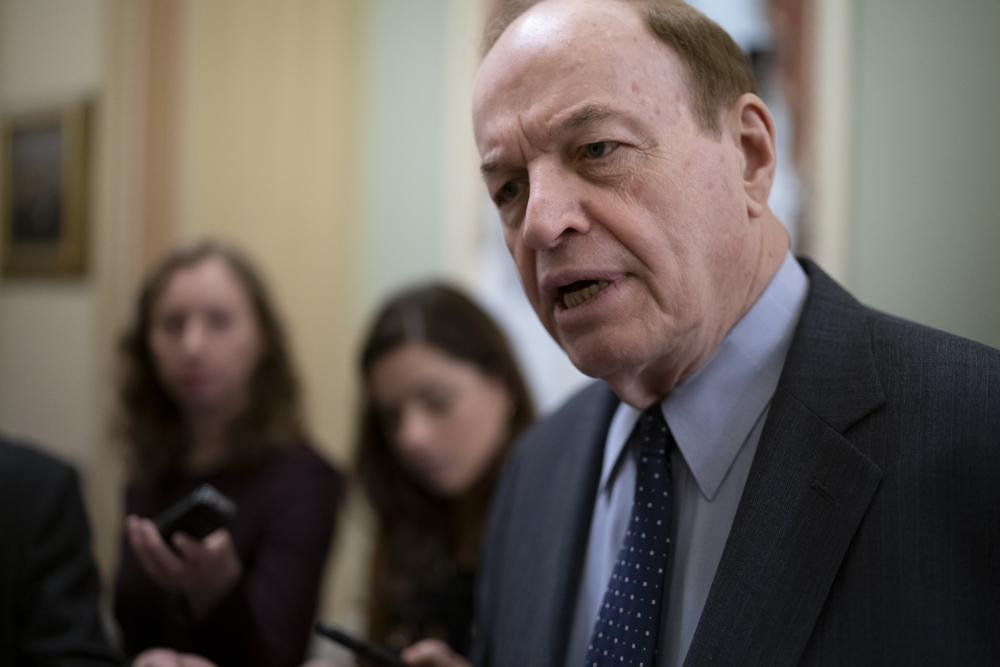

Outgoing senators Richard Shelby and Richard Burr back U.S. recognition for 2 state tribes

Testifying before Congress, Chief Framon Weaver said his Alabama-based tribe, with roots dating back to the 1830s, held a distinction no one else wanted when it came to being recognized by the U.S. government, a stamp of approval that can mean millions in federal funding for Native American groups. “It is clear that our tribe, the MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians, (is) the literal poster child for the structural failures evident in the federal recognition process,” Weaver told a committee. That was in 2012, so long ago that Weaver is no longer chief. The MOWAs are still seeking federal recognition, and they’re one of two state-recognized tribes hoping Congress will right what they see as wrongs of the past with the help of two influential U.S. senators who are retiring. It’s an issue entwined not just with history but with the possibility of gambling revenues. Alabama Sen. Richard Shelby, the senior Republican on the Appropriations Committee, is sponsoring legislation that would provide federal recognition to the roughly 6,500-member MOWA Band. GOP Sen. Richard Burr is handling similar legislation for the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, which with 60,000 members, calls itself the nation’s largest tribe not recognized by the federal government. Both groups contend the process for gaining federal recognition has become adulterated and now favors money over history. They say that’s partly because of the billions generated by Indian gambling, something they can’t offer because of the lack of federal acknowledgment. Similar recognition bills have failed repeatedly in the past, and it’s unclear whether either one will win approval this year. But the current chief of the MOWA Band, Lebaron Byrd, has taken over Weaver’s lobbying effort and hopes a final use of Shelby’s pull will mean the difference this time. “We always are optimists,” he said. “We don’t give up hope.” Shelby’s office said Friday the MOWA bill is in the Senate Indian Affairs Committee, where it had a hearing in March. Burr’s office didn’t respond to an email seeking comment. Byrd said obtaining federal recognition would mean between $50 million and $100 million initially in benefits, including health care, education, and economic development for the MOWA, who take their name from the band’s location along the Mobile-Washington county line of southwest Alabama about 30 miles (48 kilometers) north of Mobile. Passage of the Lumbee bill would cost about $363 million in expected spending from 2024-2027, according to an assessment by the Congressional Budget Office. The largest share, roughly $247 million, would come from benefits offered by the Indian Health Service, it said. Both bills are opposed by a coalition of tribes already acknowledged by the U.S. government. A branch of the Bureau of Indian Affairs determines whether groups qualify as tribes through anthropological, genealogical, and historical studies. Groups that lose recognition bids before the agency can challenge those decisions through administrative appeals or lawsuits, something the MOWA have tried and failed. The Lumbee gained partial federal recognition through a bill in 1956 but are still blocked from key federal programs, a decision they continue fighting more than six decades later. Politics shouldn’t be allowed to short-circuit the process that other tribes have used to gain federal recognition, Native American groups opposed to the bills argued during a forum held at the U.S. Capitol in July. “It is egregious when you can buy your way in,” said Margo Gray, chairwoman of the United Indian Nations of Oklahoma. Congressional action would encroach on the rights of other tribes by cheapening the process, said Richard French, chairman of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. “When you claim to be someone that you’re not, you’re messing with the other peoples’ sovereignty,” he said. More than 140 tribes are lined up against the bills, opponents say. Both the MOWA Band and the Lumbee Tribe contend history is on their side, even if other tribes aren’t. First recognized by Alabama in 1979, the MOWA Band says it is descended from Choctaws who remained in the area after Native Americans were forced to move west in the 1830s to make way for white settlers. Purposely keeping a low profile and with only sparse written records to avoid detection after other groups were forced out, the MOWA Band was typically overlooked during the decades when Alabama was segregated by race. Members lived in the same rural community near the Mississippi line where many remain, said Byrd, the current chief. The MOWAs sought federal recognition but were refused by the government in 1997 after a study determined the group wasn’t part of historical Choctaw groups, and that only 1% of its members had documented Indian heritage. Subsequent appeals and a lawsuit failed, leading to the push for congressional action on acknowledgment. First recognized by the state of North Carolina in 1885, the Lumbee have been seeking federal acknowledgment since 1888. Describing themselves as survivors of tribal nations from the Algonquian, Iroquoian, and Siouan language families, they live mainly in four counties in the southern part of the state. Lumbee member Arlinda Locklear, an attorney who specializes in tribal law in Washington, D.C., said the passage in 1988 of federal legislation that allowed gambling operations by federally recognized tribes made it more difficult for new groups to gain recognition. Existing tribes didn’t want to risk divvying up markets and gaming revenues with upstarts, she said. “That’s what’s given the opposition wings in terms of the Lumbee,” Locklear said. While the Indian Gaming Association said revenues nationwide exceeded $39 billion last year, the Lumbee have denied that gambling is their prime reason for seeking recognition. Instead, the tribes describe gaming as “the least of all motives” for its decades-long pursuit. The Alabama tribe nearly a decade ago opened a video gaming operation in a small building that’s still located near the tribal office, but it was quickly shut down by authorities because the group lacked federal recognition. Federal recognition could finally open the door to gaming operations, but the MOWA would be in competition with Alabama’s only federally recognized tribe, the Poarch Band

Family of financier of last U.S. slave ship breaks silence

Descendants of the Alabama steamship owner responsible for illegally bringing 110 African captives to America aboard the last U.S. slave ship have ended generations of public silence, calling his actions more than 160 years ago “evil and unforgivable.” In a statement released to NBC News, members of Timothy Meaher’s family — which is still prominent around Mobile, Alabama — said that what Meaher did on the eve of the Civil War “had consequences that have impacted generations of people.” “Our family has been silent for too long on this matter. However, we are hopeful that we — the current generation of the Meaher family — can start a new chapter,” said the statement. Two members of the Meaher family didn’t respond to messages seeking additional comment Friday. The statement came amid the release of “Descendant,” a new documentary about the people who were brought to the United States aboard the slave ship Clotilda and their families. The film was acquired by Netflix and Higher Ground, the production company of Barack and Michelle Obama. The Meaher family has started meeting with leaders of the community in around Africatown, the community begun by the Africans in north Mobile after they were released from slavery at the end of the Civil War in 1865, the statement said. Darron Patterson, a descendant of Clotilda captive Pollee Allen, said he met twice last month with a Meaher family member who contacted him through an intermediary. The discussions were cordial but didn’t delve deeply into details of their shared history, he said. “Our conversations were just about who we are as people,” he said. “I think it’s important that we begin there.” Patterson was president of the Clotilda Descendants Association at the time. The current president, Jeremy Ellis, said the organization had been in contact with the Meaher family by email since the NBC story aired on Sunday Today, and members hoped for face-to-face talks. ’I am interested in learning and seeking answers from the Meaher family about historical documents, artifacts, and oral histories that can bring clarity to descendants,” Ellis said. The Clotilda, a wooden schooner, was the last ship known to bring captives to the American South from Africa for enslavement. Decades after Congress outlawed the international slave trade, the Clotilda sailed from Mobile on a trip funded by Timothy Meaher, whose descendants still own millions of dollars worth of real estate around the city. A state park in Mobile Bay bears the family’s name. The Clotilda’s captain took his human cargo off the ship in Mobile and set fire to the vessel to hide evidence of the journey. The people, all from West Africa, were enslaved. Remains of the ship were discovered mostly intact on the muddy river bottom about four years ago, and researchers are still trying to determine the best way to preserve what’s left of the wreck, which many in Africatown hope will become part of a resurgence of their community. The statement said Meaher family members “believe that the story of Africatown is an important part of history that needs to be told.” “Our goal is to listen and learn, and our hope is that these conversations can help guide the actions our family takes as we work to be better partners in the community,” it said. The statement “falls short” because it fails to mention two other Meaher brothers who conspired with Timothy Meaher and the family’s decision to lease land to paper companies responsible for pollution around Africatown, Ellis said. While some members of the Africatown community have advocated for reparations for Clotilda descendants, the family’s statement made no mention of that topic. The fact that the family has started a conversation with slave descendants could be a lesson to other families whose ancestors were involved in the slave trade, Patterson said. “I hope that what the Meaher family is showing here rubs off on the families of other enslavers,” he said. Republished with the permission of The Associated Press.