2020 Watch: Messy primary finally meets election year

The presidential politics calendar turned to 2020 nearly a year ago. This week, the actual date catches up. What we’re watching as the preseason closes and election year opens: Days to Iowa caucuses: 35 Days to general election: 309 THE NARRATIVE The ups, downs and swerves of 2019 yielded a stable top slate. Former Vice President Joe Biden leads most national polls of Democratic primary voters, with Sens. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts within striking distance. Yet in the first caucus state of Iowa and the first primary state of New Hampshire, there’s a jumble of Biden, Sanders, Warren and Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Indiana. At first glance, it’s a clean choice: Biden and Buttigieg hail from the center-left; Warren and Sanders come from the progressive left. Reality is more layered. All four have weaknesses within Democrats’ diverse electorate; each makes a different case for carrying the banner against President Donald Trump, who is now impeached but a near certainty to survive a Senate trial. If that’s not enough indecision, several wildcards — including two billionaires — still hope to scramble the contest. THE BIG QUESTIONS Money: Who can (sort of) compete with Michael Bloomberg’s wallet? The fourth-quarter fundraising period ends Tuesday. Warren and Sanders set the early curve for grassroots donations, outpacing Buttigieg and Biden, who tap traditional deep-pocketed contributors in addition to online donors. Now those small-donor juggernauts must compete with former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who’s used a share of his estimated $50 billion personal fortune to blanket television and digital advertising and build an expansive staff in Super Tuesday states. For his rivals, it’s not so much about keeping up; Bloomberg can easily outspend every other campaign, including that of fellow billionaire Tom Steyer. But there’s only so much television time for sale, and if Warren and Sanders want to plow big money into Super Tuesday, especially the expensive television markets of California, they’ll need as much cash as possible ahead of time. Biden, meanwhile, has already secured his best fundraising quarter (a relative comparison for a candidate who’s lagged other top-tier contenders). The question is whether Biden’s “best” mollifies establishment Democrats who waved red flags when he reported having less than $9 million on hand at September’s end. Money, Part II: How long can Cory Booker keep going? The year-end deadline is critical for New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker as he reaches for relevance. The last of two African American candidates (along with former Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick), Booker made a do-or-die money appeal in September, and it worked. But it’ll take more than scraping by to fund the turnaround he envisions: a surprise finish in overwhelmingly white Iowa to kick-start a dramatic rise in more diverse primary states that follow (Barack Obama’s 2008 path). Campaigns that hit big fundraising numbers tend to leak that news before Federal Election Commission filings are due. Candidates with bad news tend to wait. So, it bears watching how Booker’s team plays it to start January. Is Amy Klobuchar being overlooked in Iowa? Those previously mentioned Iowa and New Hampshire jumbles omit Amy Klobuchar. But the Minnesota senator is plugging away in both states. She just hit her 99th Iowa county (that’s all of them), demonstrating her effort to use complex caucus rules that can reward candidates with a wide geographic footprint. Notably, Klobuchar’s strategy tracks Biden. Both aim for a more consistent appeal across 1,679 precincts than Warren, Sanders and Buttigieg muster on Feb. 3. The question becomes how many precincts give both Biden and Klobuchar the minimum 15 percent support required to count toward delegates. Anyone who doesn’t hit that viability mark drops from subsequent ballots, their backers going up for grabs. Biden’s Iowa hopes depend in part on picking up moderates on realignment votes (read: Klobuchar and Buttigieg supporters). If Klobuchar is as strong as she hopes to be, she could turn that strategy around on Biden, driving him below viability and attracting his supporters on later ballots. Biden returns to Iowa this week for another bus tour, though not as lengthy as his eight-day jaunt after Thanksgiving. Is Sanders a true contender this time? Sanders lost the 2016 nomination because of Hillary Clinton’s advantage among non-white Democrats. Since then, Sanders has deepened his ties among Latinos, African Americans and other non-whites. Warren and Buttigieg are still chasing that success. Sanders’ advisers believe the senator is well-positioned to challenge Biden among non-whites if he’s able to build early momentum in New Hampshire and Iowa, where Sanders will spend New Year’s Eve. If they’re right, that would open avenues to delegates Sanders didn’t get in 2016. Is Trump’s position improving? The president has never been popular judged in a vacuum. In 2016, he won GOP primaries with pluralities and lost the general election popular vote. As president, he’s never reached majority job approval in Gallup’s polling. But he’s still hovering in the 40s, not far from where his immediate predecessors were 11 months before winning second terms. Impeachment proceedings haven’t affected Trump’s standing. Meanwhile, the same Democratic-run House that impeached him approved his new North America trade pact. Top-line economic numbers shine, even if the on-ground reality is uneven. And Trump could be on the cusp of a peace deal in Afghanistan after the Taliban ruling council on Sunday agreed to a temporary cease-fire. As frenetic as Trump’s messaging is, he proved in 2016 that he relishes framing binary choices for voters, and he’s more than convinced he has a case in 2020. THE FINAL THOUGHT Most voters are just tuning into a presidential race that’s raged for a year. They’ll find a Democratic contest featuring stark options on policy and personality, but lacking an undisputed favorite. Candidates are navigating primary politics: dancing along the progressive-liberal-moderate spectrum and carefully choosing when to go after each other. At the same time, Trump dominates the 2020 narrative, a fact demonstrated most recently as Biden spent two days talking about whether he’d testify in a Senate trial on Trump’s removal from office.

Iowa swung fiercely to Donald Trump. Will it swing back in 2020?

Few states have changed politically with the head-snapping speed of Iowa. Heading into 2020, the question is whether it’s going to change again. In 2008, its voters propelled Barack Obama to the White House, as an overwhelmingly white state validated the candidacy of the first black president. A year later, Iowa’s Supreme Court sanctioned same-sex marriage, adding a voice of Midwestern sensibility to a national shift in public sentiment. In 2012, Iowa backed Obama again. All that change proved too much, too fast, and it came as the Great Recession punished agricultural areas, shook the foundations of rural life and stoked a roiling sense of grievance. By 2016, Donald Trump easily defeated Hillary Clinton in Iowa. Republicans were in control of the governor’s mansion and state legislature and held all but one U.S. House seat. For the first time since 1980, both U.S. Senate seats were in GOP hands. What happened? Voters were slow to embrace Obama’s signature health care law. The recession depleted college-educated voters as a share of the rural population, and Republicans successfully painted Democrats’ as the party of coastal elites. Those forces combined for a swift Republican resurgence and helped create a wide lane for Trump. The self-proclaimed billionaire populist ended up carrying Iowa by a larger percentage of the vote than in Texas, winning 93 of Iowa’s 99 counties, including places like working-class Dubuque and Wapello counties, where no Republican since Dwight D. Eisenhower had won. But now, as Democrats turn their focus to Iowa’s kickoff caucuses that begin the process of selecting Trump’s challenger, could the state be showing furtive signs of swinging back? Caucus turnout will provide some early measures of Democratic enthusiasm, and of what kind of candidate Iowa’s Democratic voters — who have a good record of picking the Democratic nominee — believe has the best chance against Trump. If Iowa’s rightward swing has stalled, it could be a foreboding sign for Trump in other upper Midwestern states he carried by much smaller margins and would need to win again. “They’ve gone too far to the right and there is the slow movement back,” Tom Vilsack, the only two-term Democratic governor in the past 50 years, said of Republicans. “This is an actual correction.” Iowans unseated two Republican U.S. House members — and nearly a third — in 2018 during midterm elections where more Iowa voters in the aggregate chose a Democrat for federal office for the first time in a decade. In doing so, Iowans sent the state’s first Democratic women to Congress: Cindy Axne, who dominated Des Moines and its suburbs, and Abby Finkenauer, who won in several working-class counties Trump carried. Democrats won 14 of the 31 Iowa counties that Trump won in 2016 but Obama won in 2008, though Trump’s return to the ballot in 2020 could change all that. “We won a number of legislative challenge races against incumbent Republicans,” veteran Iowa Democratic campaign consultant Jeff Link said. “I think that leaves little question Iowa is up for grabs next year.” There’s more going on in Iowa that simply a merely cyclical swing. Iowa’s metropolitan areas, some of the fastest growing in the country over the past two decades, have given birth to a new political front where Democrats saw gains in 2018. The once-GOP-leaning suburbs and exurbs, especially to the north and west of Des Moines and the corridor linking Cedar Rapids and the University of Iowa in Iowa City, swelled with college-educated adults in the past decade, giving rise to a new class of rising Democratic leaders. “I don’t believe it was temporary,” Iowa State University economist David Swenson said of Democrats’ 2018 gains in suburban Des Moines and Cedar Rapids. “I think it is the inexorable outcome of demographic and educational shifts that have been going on.” The Democratic caucuses will provide a test of how broad the change may be. “I think it would be folly to say Iowa is not a competitive state,” said John Stineman, a veteran Iowa GOP campaign operative and political data analyst who is unaffiliated with the Trump campaign but has advised presidential and congressional campaigns over the past 25 years. “I believe Iowa is a swing state in 2020.” For now, that is not a widely held view, as Iowa has shown signs of losing its swing state status. In the 1980s, it gave rise to a populist movement in rural areas from the left, the ascent of the religious right as a political force and the start of an enduring rural-urban balance embodied by Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley and Democratic Sen. Tom Harkin. Now, after a decade-long Republican trend, there are signs of shifting alliances in people like Jenny O’Toole. The 48-year-old insurance industry employee from suburban Cedar Rapids stood on the edge of the scrum surrounding former Vice President Joe Biden last spring, trying to get a glimpse as he shook hands and posed for pictures. “I was a Republican. Not any more,” O’Toole said. “I’m socially liberal, but economically conservative. That’s what I’m looking for.” O’Toole is among those current and new former Republicans who dot Democratic presidential events, from Iowa farm hubs to working-class river towns to booming suburbs. Janet Cosgrove, a 75-year-old Episcopal minister from Atlantic, in western Iowa, and Judy Hoakison, a 65-year-old farmer from rural southwest Iowa, are Republicans who caught Mayor Pete Buttigieg’s recent trip. If such voters are a quiet warning to Trump in Iowa, similar symptoms in Wisconsin and Michigan, where Democrats also made 2018 gains, could be even more problematic. Vilsack has seen the stage change dramatically. After 30 years of Republican dominance in Iowa’s governor’s mansion, he was elected in 1998 as a former small-city mayor and pragmatic state senator. An era of partisan balance in Iowa took hold, punctuated by Democratic presidential nominee Al Gore’s 4,144-vote victory in Iowa in 2000, and George W. Bush’s 10,059-vote re-election in 2004. After the 2006 national wave swept Democrats into total Statehouse control for the

Kamala Harris ends campaign for presidential bid, citing lack of funding

Sen. Kamala Harris told supporters on Tuesday that she was ending her bid for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination, an abrupt close to a candidacy that held historic potential. “I’ve taken stock and looked at this from every angle, and over the last few days have come to one of the hardest decisions of my life,” the California Democrat said. “My campaign for president simply doesn’t have the financial resources we need to continue.” A senior campaign aide said Harris made the decision Monday after discussing the path forward with family and other top officials over the Thanksgiving holiday. Her withdrawal marked a dramatic fall for a candidate who showed extraordinary promise in her bid to become the first black female president. Harris launched her campaign in front of 20,000 people on a chilly January day in Oakland, California. The first woman and first black attorney general and U.S. senator in California’s history, she was widely viewed as a candidate poised to excite the multiracial coalition of voters that sent Barack Obama to the White House. Her departure erodes the diversity of the Democratic field, which is dominated at the moment by a top tier that is white and mostly male. “She was an important voice in the race, out before others who raised less and were less electable. It’s a loss not to have her voice in the race,” said Aimee Allison, who leads She the People, a group that promotes women of color. Harris ultimately could not craft a message that resonated with voters or secure the money to continue her run. She raised an impressive $12 million in the first three months of her campaign and quickly locked down major endorsements meant to show her dominance in her home state, which offers the biggest delegate haul in the Democratic primary contest. But as the field grew, Harris’ fundraising remained flat; she was unable to attract the type of attention being showered on Pete Buttigieg by traditional donors or the grassroots firepower that drove tens of millions of dollars to Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders. In her note to supporters, Harris lamented the role of money in politics and, without naming them, took a shot at billionaires Tom Steyer and Michael Bloomberg, who are funding their own presidential bids. “I’m not a billionaire,” she said. “I can’t fund my own campaign. And as the campaign has gone on, it’s become harder and harder to raise the money we need to compete.” Harris suffered from what allies and critics viewed as an inconsistent pitch to voters. Her slogan “For the people” referenced her career as a prosecutor, a record that was viewed skeptically by the party’s most progressive voters. Through the summer, she focused on pocketbook issues and her “3 a.m. agenda,” a message that never seemed to resonate with voters. By the fall, she had returned to her courtroom roots with the refrain that “justice is on the ballot,” both a cry for economic and social justice as well as her call that she could “prosecute the case” against a “criminal” president. At times, she was tripped up by confusing policy positions; particularly on health care. After suggesting she would eliminate private insurance in favor of a fully government-run system, Harris eventually rolled out a health care plan that preserves a role for private insurance. Stumbles, often of the campaign’s making, continued to dog Harris into the winter, stymieing her ability to capitalize on solid moments. Harris kicked off November with a well-received speech at a massive Iowa dinner, just a day after her campaign announced it would fire staff at its Baltimore headquarters and was moving some people from other early states to Iowa. Her message was regularly overshadowed by campaign aides and allies sharing grievances with the news media. Several top aides decamped for other campaigns, one leaving a blistering resignation letter. “Because we have refused to confront our mistakes, foster an environment of critical thinking and honest feedback, or trust the expertise of talented staff, we find ourselves making the same unforced errors over and over,” Kelly Mehlenbacher wrote in her letter, obtained by The New York Times. Mehlenbacher now works for businessman Bloomberg’s campaign. With Harris’ exit, 15 Democrats remain in the race for the nomination. Several praised her on Tuesday. Former Vice President Joe Biden, who had a memorable debate stage tussle with Harris this summer, called the senator a “solid person, loaded with talent.” Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders commended Harris for “running a spirited and issue-oriented campaign.” New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, one of two black candidates still in the campaign, called Harris a “trailblazer.” Harris anchored her campaign in the powerful legacy of pioneering African Americans. Her campaign launch on the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday included a nod to Shirley Chisholm, the New York congresswoman who sought the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination 47 years ago earlier. One of her first stops as a candidate was to Howard University, the historically black college that she attended as an undergraduate. She spent much of her early campaign focusing on South Carolina, which hosts the first Southern primary and has a significant African American population. But Harris struggled to chip away at Biden’s deep advantage with black voters who are critical to winning the Democratic nomination. Harris and her aides believe she faced an uphill battle — and unfair expectations for perfection — from the start as a woman of color. Her campaign speech included a line about what Harris called the “donkey in the room,” a reference to the thought that Americans wouldn’t elect a woman of color. Harris often suggested it was criticism she faced in her other campaigns — all of which she won. Her departure from the presidential race marks her first defeat as a political candidate. Associated Press writers Steve Peoples in New York and Bill Barrow in Mason City, Iowa, contributed to this report. By Kathleen Ronayne and Nicholas Riccardi Associated Press. Republished with the Permission of the Associated Press.

Can 2020 democratic candidates break through the turkey coma?

Presidential politics move fast. What we’re watching heading into a new week on the 2020 campaign: Days to Iowa caucuses: 70 Days to general election: 344 THE NARRATIVE The presidential race comes to a an abrupt pause this week as voters and candidates alike shift their focus to food, football and family. The bar will be high for any new narrative to emerge over the Thanksgiving holiday, which means the Democratic primary will be locked in a four-way muddle at the top as newly announced candidate Michael Bloomberg spends big to exploit questions about his rivals and to attack President Donald Trump. THE BIG QUESTIONS Can anyone break through the food coma? With just 10 weeks until voting begins, very few candidates in the crowded Democratic race can afford another week without making progress in addressing their glaring liabilities. The same could be said for Trump, who’s facing the prospect of impeachment as his party struggles with a revolt from women and suburban voters. But there’s likely little the candidates can do on a holiday week that they haven’t already done to change the direction of the dinner table conversation. Can he buy love? The 2020 contest’s latest shiny object, but this has more than 30 billion reasons to be taken seriously on his first week out as a candidate. Bloomberg, whose worth is estimated at $30 billion to $50 billion, is dumping more than $30 million into a first-week advertising blitz that will almost certainly show up during your Thanksgiving football watching. The early investment has officially broken the record for the largest single-week ad buy in political history. If this kind of investment doesn’t move the needle for the New York billionaire, it’s fair to wonder if anything will. Room for another moderate at the table? For all the candidates who need to do well in Iowa in just 70 days, we’re only aware of two who are having Thanksgiving dinner there. That would be Kamala Harris, who you’ll remember said she was “moving to Iowa,” and Amy Klobuchar, who serves neighboring Minnesota in the Senate but has struggled to persuade primary voters to embrace her Midwestern pragmatism. Klobuchar is scheduled to have Thanksgiving dinner with staff at the home of a former state party chairwoman, while Harris will cheer runners at a Des Moines turkey trot and spend time with seniors. Can Pete Buttigieg take the next step? He has proven he belongs in the top tier after another strong debate performance and rising poll numbers on the ground in Iowa. But the 37-year-old small-city mayor has virtually no path to the nomination unless he dramatically improves his standing with black voters. He opens the week back in Iowa, where he’s betting everything that a strong showing in the opening primary contest will convince skeptical minority voters that he’s electable. It’s a tough road, but absent a dominant front-runner he must be taken seriously. THE FINAL THOUGHT Ten weeks before voting begins, the Democratic primary is truly wide open. There are four candidates clumped together in the top tier, and a candidate with essentially an unlimited budget just entered the race. Buckle up. 2020 Watch runs every Monday and provides a look at the week ahead in the 2020 election. By Steve Peoples AP National Politics Writer. Follow Peoples at https://twitter.com/sppeoples. Catch up on the 2020 election campaign with AP experts on our weekly politics podcast, “Ground Game.” Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

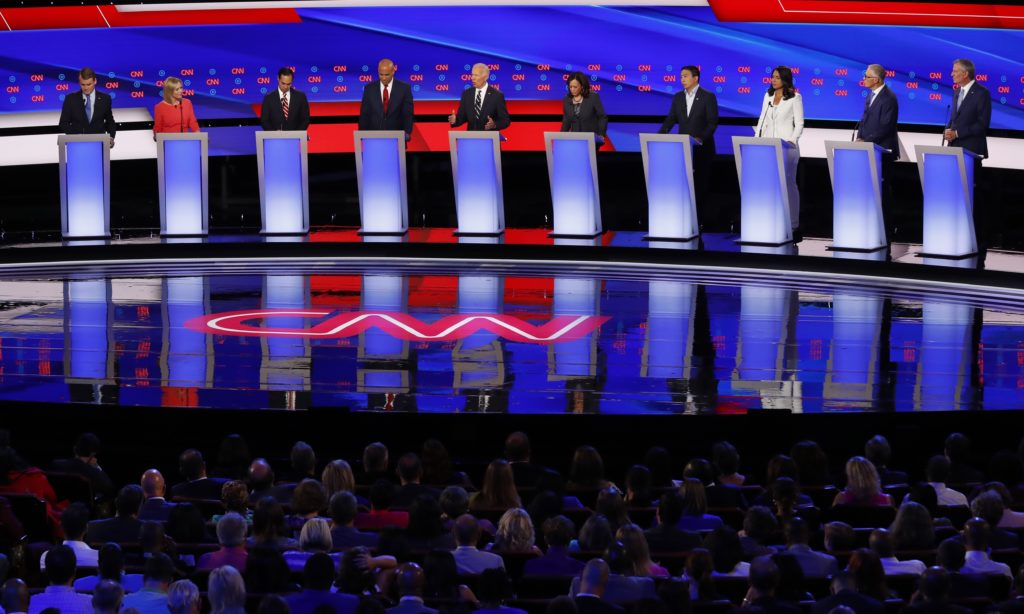

Takeaways from the democratic presidential debate

Democrats spent more time making the case for their ability to beat President Donald Trump than trying to defeat each other in their fifth debate Wednesday night. Civil in tone, mostly cautious in approach, the forum did little to reorder the field and may have given encouragement to two new entrants into the race, Mike Bloomberg and Deval Patrick. Here are some key takeaways. IMPEACHMENT CLOUD HOVERS The impeachment inquiry of President Donald Trump took up much of the oxygen early in the debate. The questions about impeachment did little to create much separation in a field that universally condemns the president. The candidates tried mightily to pivot to their agenda. Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren talked about how a major Trump donor became the ambassador at the heart of the Ukraine scandal, and reiterated her vow to not reward ambassadorships to donors. Former Vice President Joe Biden tried to tout the investigation as a measure of how much Trump fears his candidacy. Impeachment is potentially perilous to the Democratic candidates for two reasons. A Senate trial may trap a good chunk of the field in Washington just as early states vote in February. It also highlights a challenge for Democrats since Trump entered the presidential race in 2015 — shifting the conversation from Trump’s serial controversies to their own agenda. Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders warned, “We cannot simply be consumed by Donald Trump, because if you are you’re going to lose the election.” OBAMA COALITION Perhaps more than in any debate so far, Democrats explicitly acknowledged the importance of black and other minority voters. California Sen. Kamala Harris said repeatedly that Democrats must reassemble “the Obama coalition” to defeat Trump. Harris, one of three black candidates running for the nomination, highlighted black women especially, arguing that her experiences make her an ideal nominee. Another black candidate, New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, added: “I’ve had a lot of experience with black voters. … I’ve been one since I was 18.” Neither Booker nor Harris, though, has been able to parlay life experiences into strong support in the primary, in no small part because of Biden’s strong standing in the black community. Biden’s standing is also a barrier to other white candidates, including South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg, who is surging in overwhelmingly white Iowa but struggling badly with black voters in Southern states like South Carolina that have proven critical to previous Democratic nominees. Buttigieg acknowledged as much, saying he welcomes “the challenge of connecting with black voters in America who don’t yet know me.” The exchanges show that candidates seemingly accept the proposition that the eventual nominee will have to put together a racially diverse coalition to win, and that those whose bases remain overwhelmingly white (or just too small altogether) aren’t likely to be the nominee. CLIMATE CRISIS GETS AIR The climate crisis, which Democratic voters cite as a top concern, finally gained at least some attention. There were flashes of the debate Wednesday night, as billionaire environmental activist Tom Steyer swiped at Biden by suggesting the former vice president wants an inadequate, piecemeal approach to the crisis. Biden hit right back, reminding Steyer that he sponsored climate legislation as a senator in the 1980s while Steyer built his fortune in part on investments in coal. Buttigieg turned a question about the effects of Trump’s policies on farmers into a call for the U.S. agriculture sector to become a key piece of an emissions-free economy. But those details seem less important than the overall exchange — or lack thereof. Perhaps it’s the complexities of the policies involved. Or perhaps it’s just the politics. Whatever the case, the remaining field simply doesn’t seem comfortable or willing to push climate policy to the forefront, and debate moderators don’t either. HEALTH CARE GROUNDHOG DAY Before every debate, Democratic presidential campaigns aides lay out nuanced, focused arguments their candidates surely will make on the stage. And every debate seems to evolve quickly into an argument over health care. So it was again. Within minutes of the start, Warren found herself on the defensive as she explained she still supports a single-payer government run insurance system — “Medicare for All” — despite her recent modified proposal to get there in phases. Not to be outdone, Sanders reminded people that he’s the original Senate sponsor of the “Medicare for All” bill that animates progressives. “I wrote the damn bill,” he quipped. Again. Biden jumped in to remind his more liberal rivals that their ideas would not pass in Congress. The former vice president touted his commitment to adding a government insurance plan to existing Affordable Care Act exchanges that now sell private insurance policies. The debate highlights a fundamental tension for candidates: Democratic voters identify health care as their top domestic policy concern, but they also tell pollsters their top political priority in the primary campaign is finding a nominee who can defeat Trump. The top contenders did nothing to settle the argument Wednesday, instead offering evidence that the ideological tug-of-war will remain until someone wins enough delegates to claim the nomination. DID YOU HEAR THE ONE … The debate was so genial that some of the most memorable moments were the candidates’ well-rehearsed jokes. Asked what he’d say to Russian President Vladimir Putin if he’s elected to the White House, technology entrepreneur Andrew Yang said his first words would be, “Sorry I beat your guy.” Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar drew laughs for an often-repeated anecdote about how she set a record by raising $17,000 from ex-boyfriends during her first campaign. She also pushed back at fears of a female candidacy by saying, “If you think a woman can’t beat Donald Trump, Nancy Pelosi does it every day.” Booker, criticizing Biden for not agreeing to legalize marijuana, said, “I thought you might have been high when you said it.” And Harris may have issued the zinger of the night at the president when discussing his nuclear negotiations with North Korea: “Donald Trump got

Donald Trump rakes in cash while some Senate Republicans lag

President Donald Trump is raising record amounts of cash for his 2020 reelection. But that fundraising might isn’t spilling over to the most vulnerable Republicans fighting to hold onto their seats in a narrowly divided Senate. During the third quarter, former astronaut Mark Kelly took in $2.5 million more than Republican Sen. Martha McSally in Arizona. In Maine, state House Speaker Sara Gideon bested longtime Republican Sen. Susan Collins by over $1 million. And in Colorado, Cory Gardner, who led Senate Republicans’ campaign arm in 2018, barely outraised former Gov. John Hickenlooper, who had been in the race just five weeks before the quarter ended. The trouble for Republicans extends to states where they’re supposed to be on firmer ground. Iowa Sen. Joni Ernst didn’t crack $1 million and was outraised by the leading Democrat. North Carolina Sen. Thom Tillis narrowly outraised Democrat Cal Cunningham but is also facing a primary challenge from the right that has forced him to spend millions in early TV and radio ads. The lagging numbers suggest that much of the enthusiasm among the GOP base is focused on Trump and doesn’t necessarily translate to Republicans running for other offices. Democrats, meanwhile, are paying close attention to races across the board, including the House, Senate and presidency, fueling them with small-dollar donations that Republicans have struggled to counter. Fundraising prowess isn’t always an indicator of who will actually win on Election Day. But the dynamic could complicate the GOP’s effort to maintain their 53-47 grip on the Senate. This should serve as a “real wakeup call,” said Scott Reed, a senior political strategist for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, a group that has long been allied with Senate Republicans. The “ongoing Trump drama” over impeachment and other issues “drowns out all the political news back home every single night,” making it difficult for GOP candidates to get their message out, Reed said. But the challenges facing Republicans have mounted in recent weeks as the Democratic-controlled House pursues an impeachment inquiry. Instead of focusing on their own records, Republicans seeking reelection have often been barraged with uncomfortable questions about Trump’s conduct. The pressure will only grow if the Senate holds an impeachment trial, forcing these Republicans to decide whether Trump should be removed from office. “Republicans are going to struggle with fundraising and messaging if the only thing they can talk about is President Trump,” said Jonathan Kott, who was a senior adviser to Sen. Joe Manchin, a West Virginia Democrat, during his successful 2018 reelection bid. “What we found is no matter how popular the president is, you have to stand up to him when it’s good for your state. Democratic senators are finding a way to do that. Republican senators aren’t.” Democrats also have a small-dollar cash advantage. Despite an organized push, Republicans have yet to develop an online fundraising behemoth rivaling ActBlue, the Democrats’ donation platform, which enables donors across the country to direct a contribution of $1, $5 or any amount up to $2,800 with a few taps on a smartphone. “Democrats over the last several years have formulated a culture among the activist class where every time they are motivated by content or a candidate they contribute five bucks,” said Josh Holmes, an adviser to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, who is running for reelection in Kentucky and was outraised almost 5-to-1 last quarter even though the state isn’t considered a battleground. “Republicans have made strides, but we still have a long way to go.” Still, there are bright spots for the GOP. In order to regain control of the Senate, Democrats might have to win in states that have traditionally sided with Republicans over the past two decades, such as Arizona and Georgia. And some GOP candidates are successfully putting Democrats on defense. Michigan candidate John James, who came up short in his bid last year to oust Sen. Debbie Stabenow, is now beating Democratic incumbent Gary Peters in the money game. The African American, pro-Trump candidate raised $3 million, while Peters took in $2.4 million over the past three months, records show. In Georgia, where there will be two Senate seats on the ballot because of the retirement of Sen. Johnny Isakson, Democrats are still sorting out who all will run. Jon Ossoff was the top-raising Democrat in the contest to take on Republican incumbent David Perdue. But of the $1.3 million he took in, more than $500,000 was left over from his failed 2017 bid for a suburban Atlanta House seat. Perdue, meanwhile, raised about $2.5 million. While Republicans acknowledge they face an unfavorable political environment, it’s also early in the cycle. In 2018, Democrats appeared to be making strides in Senate contests as the election neared, but the party’s handling of a sexual misconduct allegation leveled against now-Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh galvanized the Republican base and helped them turn the tide. Kavanaugh denies the allegation. If Democrats were to mishandle the impeachment inquiry of Trump, it could deliver a similar jolt. “Democrats have found fundraising success pretty regularly during the last several years,” said Jesse Hunt, spokesman for the Republican Senatorial Campaign Committee. “In many cases, that’s not manifested itself into electoral victories.” By Brian Slodyski Associated Press Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

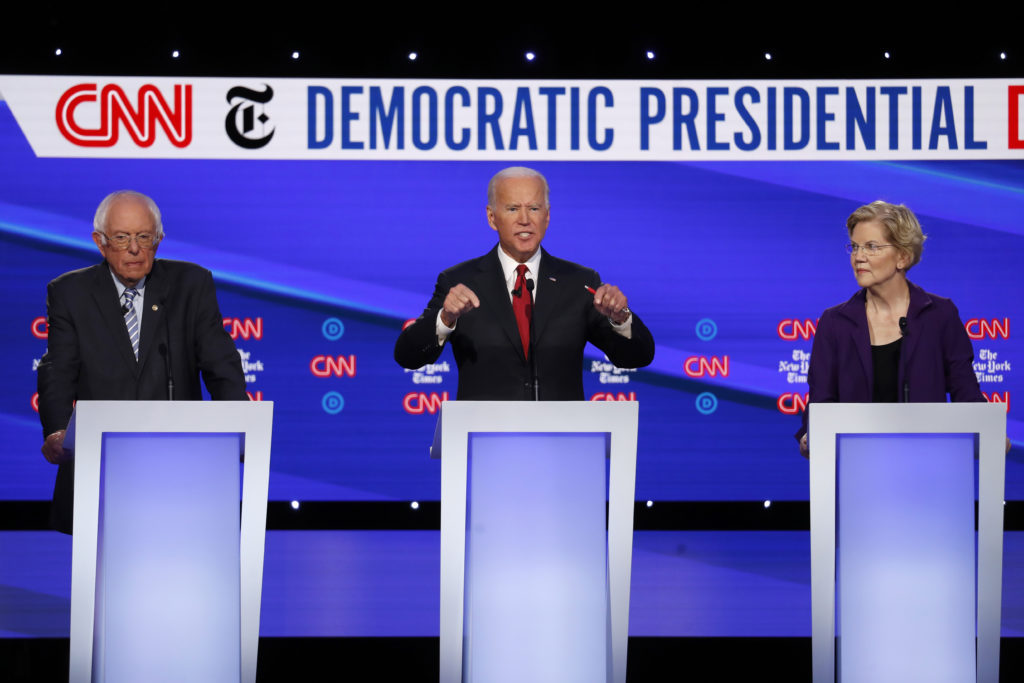

Democratic debate: Top 2020 contenders finally on same stage

Progressive Democrats Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders share the debate stage for the first time with establishment favorite Joe Biden Thursday night in a prime-time showdown displaying sharply opposing notions of electability in the party’s presidential nomination fight. Biden’s remarkably steady lead in the crowded contest has been built on the idea that the former vice president is best suited to defeat President Donald Trump next year — a contention based on ideology, experience and perhaps gender. Sanders and Warren, meanwhile, have repeatedly criticized Biden’s measured approach, at least indirectly, by arguing that only bold action on key issues like health care, the economy and climate change can build the coalition needed to win in 2020. The top-tier meeting at center stage has dominated the pre-event talk, yet each of the other seven candidates hopes for a breakout moment with the attention of the nation beginning to increase less than five months before the first primary votes are cast. “For a complete junkie or someone in the business, you already have an impression of everyone,” said Howard Dean, who ran for president in 2004 and later chaired the Democratic National Committee. “But now you are going to see increasing scrutiny with other people coming in to take a closer look.” The ABC News debate is the first limited to one night after several candidates dropped out and others failed to meet new qualification standards. A handful more candidates qualified for next month’s debate, which will again be divided over two nights. Beyond Biden and Sens. Warren and Sanders, the candidates on stage Thursday night include Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar, New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg, California Sen. Kamala Harris, New York businessman Andrew Yang, former Texas Rep. Beto O’Rourke and former Obama administration Housing chief Julian Castro. Viewers will see the diversity of the modern Democratic Party. The debate, held on the campus of historically black Texas Southern University, includes women, people of color and a gay man, a striking contrast to the Republicans. It will unfold in a rapidly changing state that Democrats hope to eventually bring into their column. Perhaps the biggest question is how directly the candidates will go after one another. Some fights that were predicted in previous debates failed to materialize with candidates like Sanders and Warren in July joining forces. The White House hopefuls and their campaigns are sending mixed messages about how eager they are to make frontal attacks on anyone other than Trump. That could mean the first meeting between Warren, the rising progressive calling for “big, structural change,” and Biden, the more cautious but still ambitious establishmentarian, doesn’t define the night. Or that Harris, the California senator, and Buttigieg, the mayor of South Bend, Indiana, look to reclaim lost momentum not by punching rivals but by reemphasizing their own visions for America. Biden, who has led most national and early state polls since he joined the field in April, is downplaying the prospects of a clash with Warren, despite their policy differences on health care, taxes and financial regulation. “I’m just going to be me, and she’ll be her, and let people make their judgments. I have great respect for her,” Biden said recently as he campaigned in South Carolina. Warren says consistently that she has no interest in going after Democratic opponents. Yet both campaigns are also clear that they don’t consider it a personal attack to draw sharp policy contrasts. Warren, who as a Harvard law professor once challenged then-Sen. Biden in a Capitol Hill hearing on bankruptcy law, has noted repeatedly that they have sharply diverging viewpoints. Her standard campaign pitch doesn’t mention Biden but is built around an assertion that the “time for small ideas is over,” an implicit criticism of more moderate Democrats who want, for example, a public option health care plan instead of single-payer or who want to repeal Trump’s 2017 tax cuts but not necessarily raise taxes further. Biden, likewise, doesn’t often mention Warren or Sanders. But he regularly contrasts the price tag of his public option insurance proposal to the single-payer system that Warren and Sanders back. In a pre-debate briefing, Biden campaign officials said he would reject the premise that he’s an incrementalist, either in his long career as a senator and vice president or in his proposals for a would-be presidency. In an apparent rebuke of Warren, known for her policy plans, the advisers said Biden will hit on the idea that “we need more than just plans, we need action, we need progress.” Health care will top the list of examples, they said. They note that Biden’s proposal for a government-run “public option” to compete with private insurance still would be a major market shift, even if it stops short of Sanders’ and Warren’s proposal for a government insurance system that would effectively end the existing private insurance system. And, by extension, the difference may make Biden’s plan more likely to make it through Congress, they contend. There are indirect avenues to chipping away at Biden’s advantages, said Democratic consultant Karen Finney, who advised Hillary Clinton in 2016. Finney noted Biden’s consistent polling advantages on the question of which Democrat can defeat Trump. A Washington Post-ABC poll this week found that among Democrats and Democratic-leaning voters, 45 percent thought Biden had the best chance to beat Trump, though just 24 percent identified him as the “best president for the country” among the primary field. “That puts pressure on the others to explain how they can beat Trump,” Finney said.Voters, she said, “want to see presidents on that stage,” and Biden, as a known quantity, already reaches that threshold. “If you’re going to beat him, you have to make your case.”Harris, said spokesman Ian Sams, will “make the connection between (Trump’s) hatred and division and our inability to get things done for the country.” Buttigieg, meanwhile, will have an opportunity to use his argument for generational change as an indirect attack on the top

10 democrats set for next debate as several others miss cut

Struggling Democratic presidential candidates are facing the bad news that they are not among the 10 who have qualified for the next debate, a predicament that is likely to spell doom for their campaigns. Hours ahead of a midnight Wednesday deadline to qualify, New York Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand announced she was dropping out of the race after spending at least $4 million on advertising in recent months to qualify. Billionaire climate change activist Tom Steyer, Montana Gov. Steve Bullock and self-help guru Marianne Williamson were also among those missing September’s debate, as were Colorado Sen. Michael Bennet, Hawaii Rep. Tulsi Gabbard and a handful of others. To appear on stage in Houston next month, they had to hit 2 percent in at least four approved public opinion polls while securing 130,000 unique donors . Two new polls released Wednesday affirmed that they were all below the threshold. The question shifted from who would qualify for the following debate to who would stay in the race. “Our rules have ended up less inclusive … than even the Republicans,” Bullock said on MSNBC, referring to the thresholds set by the Democratic National Committee. “It is what it is.” The 10 candidates who qualified for September’s debate are Joe Biden, Cory Booker, Pete Buttigieg, Julián Castro, Kamala Harris, Amy Klobuchar, Beto O’Rourke, Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren and Andrew Yang. In a still-crowded Democratic field, not qualifying for the debate was expected to severely cripple a candidate’s prospects. However, several have pledged to forge on in hopes of reaching the requirements in time for the next debate, in October. Although earlier debates had lower thresholds, the DNC raised the stakes for the fall debates. “We believe you need to show progress in your campaign,” said Democratic Party spokeswoman Xochitl Hinojosa. “There hasn’t been one candidate in 40 years who has polled under 2% the fall ahead of a primary and has gone on to be the Democratic nominee.” The DNC designed the requirements to bring order to an unwieldy field of more than 20 White House hopefuls, while elevating the role of online grassroots donors who are among the party’s most fervent supporters. In some ways, the party has succeeded. But the process has drawn complaints from those unlikely to make the cut. They argue that the rules are arbitrary and have forced candidates to pour money into expensive online fundraising operations that can sometimes charge as much as $90 for every dollar raised. Bennet said the threshold favored Steyer, and a memo by his campaign accused the billionaire of trying to buy his way into the debate. “Other candidates have had to spend millions to acquire donors on Facebook, instead (of) communicating with voters and laying the groundwork to beat” President Donald Trump, the Bennet campaign memo stated. Steyer, a late entry in the race, was the closest to qualifying but acknowledged Wednesday night that he too had fallen short. “While I’m disappointed that I won’t be on the debate stage in Houston this month, I’m excited by all the support you’ve shown us,” he tweeted to supporters. “We started this campaign to get corporate influence out of politics, and I won’t stop fighting until the government belongs to the people again.” In a separate letter to Democratic Party Chairman Tom Perez, Bennet’s campaign asked how the DNC decided which polls to allow and questioned why Democrats were trying to narrow the field months before Iowa caucuses. Yet Hinojosa, the DNC spokeswoman, said those who are upset have had ample time to build support and reach the thresholds. Instead, most have consistently polled at 1% or below. “We are asking Democratic candidates to hit 2 percent in four polls. That is not a high threshold,” said Hinojosa, who added the DNC is accepting the results from 21 polls. Steyer and Gillibrand both poured millions of dollars into Facebook and TV ads to boost their standing in recent months. While Steyer met the donor threshold, he was one poll shy. Gillibrand was three polls away and had yet to lock in enough donors. Gabbard was two polls away from qualifying, and Williamson was three polls away.Several others who struggled had already chosen to drop out. Washington Gov. Jay Inslee, Massachusetts Rep. Seth Moulton and former Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper all recently ended their campaigns. With no more than 10 participants, the September debate would be the first of the cycle held on a single night. Earlier debates featured 20 candidates split across two nights.Biden, the race’s early front-runner, said he would like the field to winnow even further. “I’m looking forward to getting to the place, assuming I’m still around, that it gets down to a smaller number of people so we can have more of a discussion instead of one-minute assertions,” the former vice president said Wednesday while campaigning in Spartanburg, South Carolina. By Brian Slodysko Associated Press Associated Press writer Bill Barrow in Spartanburg, South Carolina, contributed to this report. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Making a case to women: Donald Trump female defenders go on offense

The Donald Trump campaign has a message for its female supporters: It’s time to come out of hiding. “There’s a lot of people that are fearful of expressing their support, and I want you ladies to know it’s OK to have felt that way, but we need to move past that or the Democrats win,” said Tana Goertz, a Trump campaign adviser, at an Iowa “Women for Trump” event on Thursday. The Iowa event, held in the back room of a barbecue joint in a Des Moines suburb, was one of more than a dozen in battleground states nationwide as part of a push to make the president’s case on the economy and train volunteers. The move is a recognition of the president’s persistent deficit with women — an issue that has the potential to sink his chances for reelection. Over the course of his presidency and across public opinion polls, women have been consistently less supportive of President Donald Trump than men have. Suburban women in particular rejected Republicans in the 2018 midterm by margins that set off alarms for the party and the president. Trump himself called into a gathering of hundreds in Tampa, Florida, and insisted, to cheers: “We’re doing great with women, despite the fake news.” But polling suggests his challenges persist. The most recent Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research poll found just 30 percent of women approve of the way the president is doing his job, compared to 42 percent of men. Notably, there was no gap between Republican men and women — 80 percent of both groups said they approved of his job performance in the August poll. At an event in Troy, Michigan, a Detroit suburb viewed as key contested territory, Michigan Republican Party Chairwoman Laura Cox acknowledged that Trump’s style is a turnoff for some female voters. But she told the audience of 100 women to focus instead on what Trump had accomplished during his first term. “I get it. I say, ‘Listen, you never wonder what he thinks about people,’” she said. “Some people may not like what he says. But he delivers and has a very good track record of deliverables. And that’s what’s important. I try to get people focused on that, not the personality.” In Iowa, Goertz listed a number of ways that she said women are benefiting from Trump’s presidency, including low unemployment, job creation and “safety” — and she said his immigration policy was a winner there. “When I lay my head down at night, I want to know that my children are safe, that a terrorist is not going to come into our country,” she said. Similar events were scheduled in 13 battleground states, including North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Georgia and Ohio. The events, led by surrogates including White House counselor Kellyanne Conway and former Fox News host Kimberly Guilfoyle, sought to train attendees to be volunteers and what the campaign describes as “ambassadors” for the reelection effort. Among the women in attendance in Troy was Cara McAlister, a sales representative from the nearby suburb of Bloomfield Township. She said Trump’s 2016 candidacy inspired her to get more involved politically, and she became a GOP precinct delegate and canvassed door to door for him. She has friends who were afraid to reveal their support for Trump because they fear backlash. So she invites them to meetings like Thursday’s gathering. “They really enjoy being in an atmosphere where they feel free to express their support for the president,” said McAlister, who was wearing a white “Make America Great Again” cap and blue Trump-Pence shirt and who described herself as “middle age.” ”They tend to want to go to another event.” In Iowa, Joyce Lawson, a 30-year-old barbershop owner from Norwalk, said she finds herself targeted by friends for her conservative views. “I’m afraid of people saying off-key stuff, like you’re racist, you’re with the Klan, just random uneducated stuff, and name-calling. So I want to have facts to stand up for my views,” she said. Trump has turned off higher-income, college educated and younger women “because of how he speaks, how he tweets,” said Republican pollster Frank Luntz, while retaining the support of older women and women with lower incomes and without college degrees.That contrast is evident in Iowa, a state Trump won by more than 9 percentage points in 2016, but one that has historically been seen as a potential swing state. Some Republican women here, like Des Moines resident Pat Inglis, have become more fervent Trump supporters over his first term. “He’s helped this country more than anybody else in the last 20 years,” the 70-year-old retiree said. She added that Democratic attacks against the president, and the leftward tilt of the Democratic Party, have made her all the more enthusiastic toward Trump. Others like Mary Miner, a lifelong Republican and small-business owner from rural Iowa, were driven away from the GOP by Trump. “I’m astonished anyone could support him,” the 61-year-old Miner said. “If my party is going to support that, I’m done with ’em. I’m a Democrat and that’s it.” Recent focus groups show that women have dug in on their views, suggesting there are fewer women open to being persuaded, Luntz said. “It’s become more pronounced where those who don’t like him are overtly hostile and those who do like him will stand up for him aggressively,” Luntz said. “They are even more outspoken than men. They are even more dismissive. It’s spoken with attitude and with venom. And I think it’s because they take it personally.” As a result, he said, the election is likely to come down to a very narrow demographic — married professional mothers with teenagers, he says — who credit Trump for a booming economy but are turned off by his style. “They like what he’s done, but they don’t like how he’s done it,” he said. “Do you want to focus on the ingredients, or do you want to focus on the casserole?”

Democrats take a look at a practical health care approach

Democratic voters appear to be reassessing their approach to health care, a pragmatic shift on their party’s top 2020 issue. While “Medicare for All” remains hugely popular, majorities say they’d prefer building on “Obamacare” to expand coverage instead of a new government program that replaces America’s mix of private and public insurance. Highlighted by a recent national poll, shifting views are echoed in interviews with voters and the evolving positions of Democratic presidential candidates on a proposal that months ago seemed to have growing momentum within their party. Several have endorsed an incremental approach rather than a government-run plan backed by Sens. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts. It could mean trouble for Sanders and his supporters, signaling a limit to how far Democratic voters are willing to move to the left and an underlying skepticism that Americans will back such a dramatic change to their health care. “We hear Medicare for All, but I’m not absolutely certain what that means and what that would then mean for me,” said Democrat Terrie Dietrich, who lives near Las Vegas. “Does it mean that private insurance is gone forever?” Dietrich, 74, has Medicare and supplements that with private insurance, an arrangement she said she’s pretty comfortable with. She thinks it’s important that everyone has health care, not just those who can afford it. She said she would support Medicare for All if it was the only way to achieve that. But “I don’t think we can ever get it passed,” Dietrich added. Erin Cross, her 54-year-old daughter and also a Democrat, said she’s not comfortable with switching to a system in which a government plan is the only choice. She said Democrats won’t be able to appeal to Republicans unless they strike a middle ground and allow people to keep their private insurance. “We’ve got to get some of these other people, these Republican voters, to come on over just to get rid of Trump,” she said. Democratic presidential candidates also have expressed skepticism. California Sen. Kamala Harris’ new plan would preserve a role for private insurance. New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker is open to step-by-step approaches. Meanwhile, health care moderates including former Vice President Joe Biden have been blunt in criticizing the government-run system envisioned by Sanders. In Nevada, the early voting swing state that tests presidential candidates’ appeal to labor and a diverse population, moderate Democrats have won statewide by focusing on health care affordability and preserving protections from President Barack Obama’s law. Nationwide, 55 percent of Democrats and independents who lean Democratic said in a poll last month they’d prefer building on Obama’s Affordable Care Act instead of replacing it with Medicare for All. The survey by the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation found 39% would prefer Medicare for All. Majorities of liberals and moderates concurred. On a separate question, Democratic support for Medicare for All was a robust 72 percent in July, but that was down from 80 percent in April, a drop Kaiser says is statistically significant but not necessarily a definitive downward trend. That said, Kaiser pollster Liz Hamel said it wouldn’t be surprising if it turned into one. On big health care ideas, she said, “as the public starts seeing arguments for and against, we often see movement.” The Kaiser survey also found broad backing for the public-option alternative that moderates are touting, a government plan that would compete with but not replace private insurance. Eight-five percent of Democrats supported that idea, along with 68 percent of independents. Republicans were opposed, 62 percent to 36 percent. Large increases in federal spending and a significant expansion of government power are often cited as arguments against Medicare for All. However, the main criticism Democrats are hearing from some of their own candidates is that the Sanders plan would force people to give up their private health insurance. Under the Vermont senator’s legislation, it would be unlawful for insurers or employers to offer coverage for benefits provided by the new government plan. Ohio Rep. Tim Ryan argued during the last round of Democratic debates that that’s problematic for union members with hard-fought health care plans secured by sacrificing wage increases. However, Sanders has long asserted his plan will allow unions to obtain bigger wage increases by taking health care out of the equation. In interviews with The Associated Press, union workers in Nevada said they worried about how Medicare for All would affect their coverage. Chad Neanover, prep cook at the Margaritaville casino-restaurant on the Las Vegas Strip, said he would be reluctant to give up the comprehensive insurance that his union has fought to keep. He has asthma, and his wife is dealing with diabetes. The union’s plan has no monthly premium cost and no deductible. “I don’t want to give up my health insurance. I’ve personally been involved in the fight to keep it,” said Neanover, 44. “A lot of people have fought to have what we have today.”Savannah Palmira, a 34-year-old union construction worker in Las Vegas, said she’s open to supporting Medicare for All, but wants to know specifically what it would look like, how the country would transition and how it would affect her plan. “That’s one of the biggest things that I love about being in the union, is our quality health care,” Palmira said. Medicare for All backers say their plan has been unfairly portrayed. “The shift in polling on Medicare for All is a direct result of mischaracterizations by opponents,” said Rep. Ro Khanna, Democrat-California, a Sanders campaign co-chair. People are most interested in keeping their own doctors, Khanna added, and Medicare for All would not interfere with that. Longtime watchers of America’s health care debate see new energy among Democrats, along with a familiar pattern. “The long-standing history of health reform is that people want to hang on to what they have,” said Georgetown University public policy professor Judith Feder, who was a health policy adviser in the Clinton administration. Nonetheless, she noted a common interest

Donald Trump ties U.S. success to 2nd term: ‘You have to vote for me’

President Donald Trump sought to reassure his supporters about the state of the U.S. economy despite the stock market volatility and told rallygoers in New Hampshire, a state that he hopes to capture in 2020, that their financial security depends on his reelection. “Whether you love me or hate me you have to vote for me,” Trump said. Speaking to a boisterous crowd at Southern New Hampshire University Arena, Trump dismissed the heightened fears about the U.S. economy and a 3 percent drop Wednesday in the Dow Jones Industrial Average, which was fueled by a slowing global economy and a development in the bond market that has predicted previous recessions. Avoiding an economic slump is critical to Trump’s reelection hopes. “The United States right now has the hottest economy anywhere in the world,” Trump said. Trump, who reached the White House by promising to bring about a historic economic boom, claimed, as he often does, that the markets would have crashed if he had lost his 2016 bid for the presidency. And he warned that if he is defeated in 2020, Americans’ 401(k) retirement accounts will go “down the tubes.” The Republican president also defended his tactics on trade with China. He has imposed 25 percent tariffs on $250 billion of imports from China and has threatened to hit the remaining $300 billion worth of Chinese imports with 10 percent tariffs. He has delayed that increase on about half of those items to avoid raising prices for U.S. holiday shoppers. He said China wants to make a trade deal with the U.S. because it’s costing the country millions of jobs, but he claimed that the U.S. doesn’t need to be in a hurry. “I don’t think we’re ready to make a deal,” Trump said. Trump’s rally was the first since mass shootings in El Paso, Texas, and Dayton, Ohio, killed 31 people and wounded dozens more. The shootings have reignited calls for Congress to take immediate action to reduce gun violence. Trump said the U.S. can’t make it more difficult for law-abiding citizens to protect themselves, but he advocated for expanding the number of facilities to house the mentally ill without saying how he would pay for it. “We will be taking mentally deranged and dangerous people off of the streets so we won’t have to worry so much about them,” Trump said. “We don’t have those institutions anymore, and people can’t get proper care. There are seriously ill people and they’re on the streets.” Along with discussion of the economy and guns, Trump hit a number of other topics, accusing the European Union of being “worse than China, just smaller”; bragging about his 2016 electoral victories in Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania; and calling it a “disgrace” that people were throwing water on police officers in New York. The rally was interrupted about a half an hour in by a handful of protesters near the rafters of the arena. As the protesters were being led out, a Trump supporter wearing a “Trump 2020” shirt near them began enthusiastically shaking his fist in a sign of support for the president. But Trump mistook him for one of the protesters and said to the crowd: “That guy’s got a serious weight problem. Go home. Start exercising. Get him out of here, please.”After a pause, he added, “Got a bigger problem than I do.” New Hampshire, which gave Trump his first GOP primary victory but favored Hillary Clinton in the 2016 general election, is doing well economically, at least when using broad measures. But beneath the top-line data are clear signs that the prosperity is being unevenly shared, and when the tumult of the Trump presidency is added to the mix, the state’s flinty voters may not be receptive to his appeals. An August University of New Hampshire Survey Center poll found that 42 percent of New Hampshire adults approve of Trump while 53 percent disapprove. The poll also showed that 49 percent approve of Trump’s handling of the economy and 44 percent disapprove. Some Democratic presidential campaigns are holding events to capitalize on Trump’s trip. Joe Biden’s campaign set up down the street from the arena to talk to voters and enlist volunteers. A group for Pete Buttigieg’s campaign gathered in nearby Concord to call voters about his support for new gun safety laws. And Cory Booker urged Trump to cancel the speech and instead order Congress to take immediate action to prevent gun violence. At 2.4 percent, New Hampshire’s seasonally adjusted unemployment rate for May was among the lowest in the nation. But wage growth is significantly below national gains. Average hourly earnings rose a scant 1 percent in New Hampshire in 2018, lagging the 3 percent gain nationwide, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In other ways, like the home ownership rate — first in the nation — and median household income — seventh in the U.S. — the state is thriving, according to census data. New Hampshire’s four Electoral College votes are far below that of key swing states like Florida, Wisconsin and Michigan, but its influence can prove powerful in close election years like 2000, when George W. Bush’s victory in the state gave him the edge needed to win the White House. By Kevin Freking Associated Press AP Economics Writer Josh Boak and AP Polling Editor Emily Swanson in Washington and Associated Press writer Hunter Woodall in Manchester, N.H., contributed to this report. Republished with permission of the Associated Press.

John Hickenlooper ending his 2020 White House bid

John Hickenlooper will drop out of the Democratic presidential primary on Thursday, according to a Democrat close to him. The former two-term Colorado governor, who ran as a moderate warning of the perils of extreme partisanship, struggled with fundraising and low polling numbers. His planned departure from the 2020 race was confirmed Wednesday night by a Democrat who wasn’t authorized to speak publicly before the announcement and spoke to The Associated Press on the condition of anonymity. Hickenlooper, 67, is not expected to announce a decision Thursday on whether he will run for Senate in Colorado, though he has been discussing the possibility with advisers. Republican Sen. Cory Gardner, up for reelection in 2020, is considered one of the most vulnerable senators in the country because of Colorado’s shift to the left. Hickenlooper became a political giant in Colorado for his quirky, consensus-driven and unscripted approach to politics. He once jumped out of a plane to sell a ballot measure to increase state spending and won two statewide elections in a purple state during Republican wave years. He was previously the mayor of Denver. He launched his longshot White House bid in March, promising to unite the country. Instead, he quickly became a political punch line. Shortly before taking his first trip to Iowa as a candidate, Hickenlooper, who became a multimillionaire founding a series of brewpubs, balked at calling himself a capitalist on national television. Then, at a CNN town hall, he recounted how he once took his mother to see a pornographic movie. With the campaign struggling to raise money, his staff urged Hickenlooper to instead challenge Gardner. But Hickenlooper stayed in and hired another group of staffers in a last-ditch effort to turn around his campaign. Positioning himself as a common-sense candidate who couldn’t be labeled a socialist by Republicans, Hickenlooper couldn’t make his voice heard in the crowded Democratic presidential field of about two dozen candidates. It didn’t help that, by Hickenlooper’s own admission, he’s a mediocre debater and erratic public speaker. In the end, he couldn’t even scrape together enough money for many of his trademark quirky ads, only launching one in which avid beer drinkers toast Hickenlooper by comparing him to favorite brews. Hickenlooper softened his denials of interest in the Senate in recent weeks as his campaign finances dwindled and pressure increased from other Democrats. He started telling people he’d make a decision by the end of this week. It’s unclear whether Hickenlooper plans to run against Gardner, whom national Democrats have urged him to take on since last year. He’s repeatedly said he’s not interested in the Senate and prefers an executive position. But if Hickenlooper did run against Gardner, he’d first have to get through another crowded Democratic primary field. Numerous Colorado Democrats have launched primary bids for Gardner’s seat, and many have indicated they’d stay in the race, even if Hickenlooper enters the contest. Hickenlooper isn’t the first Democratic hopeful to end his 2020 presidential bid. U.S. Rep. Eric Swalwell of California announced his departure in July. By Nicholas Riccardi Associated Press. AP Washington Bureau Chief Julie Pace contributed to this report from Washington. Republished with permission of the Associated Press.