Alabama ranks high among states discouraging abortion

According to an analysis released Tuesday by the National Partnership for Women & Families, Alabama is among the 12 worst states in America for abortion coverage and select workplace policies for women. Released to mark the 40th year under the Hyde Amendment — a legislative provision barring the use of certain federal funds to pay for abortion except in the cases of rape, incest, or to save the life of the mother — A Double Bind: When States Deny Abortion Coverage and Fail to Support Expecting and New Parents is an issue brief and map that identify obstacles faced by low-income women across the country. Since the Supreme Court handed down its 1973 decisions in Roe v. Wade, states have constructed a latticework of abortion law, codifying, regulating and limiting whether, when, and under what circumstances a woman may obtain an abortion. The analysis found Alabama does not cover abortions for Medicaid enrollees and restricts coverage of abortions in the state health care marketplace, in addition to having no workplace protections for expecting and new parents. Arizona, Georgia, Idaho, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, and Wyoming, also rank among the nation’s 12 worst states for abortion coverage and select workplace policies for women.

Census numbers reveal decline in uninsured Alabamians

Health insurance statistics released Tuesday by the U.S. Census Bureau indicate that the rate of uninsured Americans dropped in 47 states last year, including Alabama. The data reveals only one in 10 Alabamians lacked health insurance coverage in 2015, an improvement from the state’s 13.6 percent uninsured rate in 2013, the last year before the Affordable Care Act took full effect. Tuesday’s numbers come in the midst of a volatile election season, where citizens across the country continue to weigh the pros and cons of the Affordable Care Act, often called Obamacare, as they decide who they’re voting for in November. For some, Tuesday’s numbers serve as a reminder for the need for an expanded Medicaid program in the state. “[The] good news about health coverage in Alabama would be even better if the state had expanded Medicaid,” said Alabama Arise State Coordinator Kimble Forrister. “More Alabamians have coverage today than in 2013, and the Affordable Care Act deserves much of the credit for those gains. Nearly 200,000 Alabamians have signed up for health insurance through the ACA marketplace. Many of them have coverage for the first time, and all of them now have the peace of mind that comes with knowing that a medical emergency won’t lead to financial ruin.” According to Forrister, Medicaid expansion would close the coverage gap for more than 300,000 uninsured across Alabama. “That would mean a more productive workforce, thousands of new jobs and big state savings on mental health care and other services,” Forrister explained. “We’re being left out. States like Kentucky and West Virginia that have expanded Medicaid have much lower uninsured rates than those that haven’t. They’re also enjoying the job creation and cost savings that come from injecting new federal money into their budgets and economies. It’s time for Alabama to expand Medicaid and reap those same benefits.”

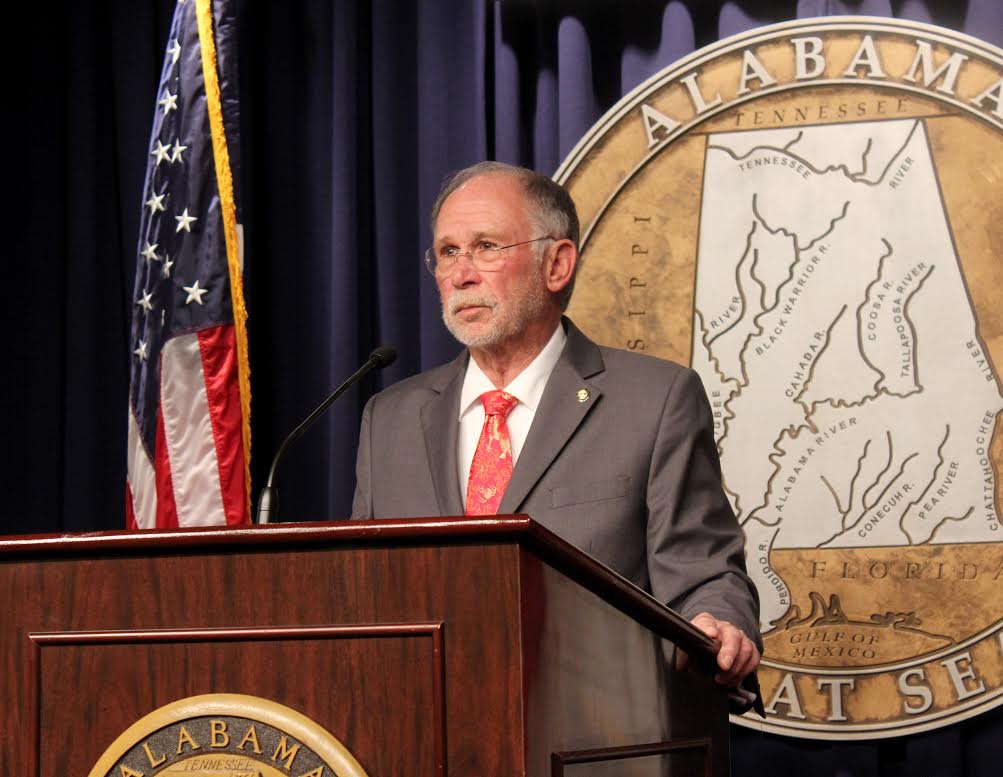

Jim McClendon: A tale of two lotteries for two budgets

Let me start by clarifying I am married to only one thing in life — my beautiful wife, El. My relationship with her is nonnegotiable. “Until death do us part” is a promise between us, not just a sweet thing to say during a wedding. I understand this is an odd way to start an editorial about the lottery. However, it is necessary because I am not married to one lottery proposal over the other, considering I’m sponsoring two, including the governor’s. The people of my district and hundreds of thousands of other Alabamians are clamoring for the right to vote on a lottery. Some are for; some are against. But everyone I talk to agrees we at least need to put the lottery to an up-or-down vote of the people. So let’s get into the meat of the lottery proposal I presented at a press conference Tuesday, along with some necessary myth busting. First, I have no qualms with anyone over a moral objection to gambling. Vote “no” and take people to the polls with you to do the same. In the meantime, answer this: Are you going to provide free clinics for sick underprivileged children? Will you do in Alabama what you do on mission trips to other states and countries? Incidentally, I have never purchased a lottery ticket. I did buy a raffle ticket at my church last Sunday. I am not supporting or opposing a lottery because of moral reasons. To me, this is simply creating an opportunity for the people of Alabama, not the Legislature, to have the final say. Second, a lottery will not bring Class III gaming (table games) to our state. Speaking of the Poarch Creek Indians, I have already been forewarned they opposed lottery terminals. I would like to point out their children enjoy premium healthcare covered by the profits of their gaming machines. That is admirable, and they should support my effort to extend the same courtesy to more than a half-million other Alabama children. Now let’s talk about the governor’s bill and my bill. During the regular session, I introduced a simple 31-word bill to begin the conversation in earnest. It obviously didn’t become law, but the conversations it started in the Legislature resulted in the bill I will introduce at the beginning of the special session. Both bills create a statewide lottery and a lottery commission. Neither will affect charitable bingo or allow casinos. My proposal will allow electronic lottery terminals in counties that have local constitutional amendments already allowing parimutuel wagering. The governor’s proposal only generates $225 million and sends 100 percent of it to the general fund budget. In contrast, my concept generates $427 million every year and divides the revenue by sending $327 million to the general fund and $100 million to the Education Trust Fund. Because of the lottery terminals, my proposal will also start generating revenue in only a matter of months, not years. Finally, I included a bond issue against future lottery revenues in order to cover the $85 million Medicaid shortfall this fiscal year. It is now up to the legislative process during the upcoming special session to determine which proposal — the governor’s, mine, or someone else’s — should go before the voters in November. Come Aug. 24, which is the cutoff for placing a constitutional amendment on the general election ballot, it is my hope my colleagues in the Alabama Senate and Alabama House give voters the right to vote on the lottery. Think about which one best provides for both the short-term fix and the long-term solution. Consider the impact on you and your family if we cannot fund Medicaid, the foundation of Alabama’s healthcare system. Call your legislators today, and tell them to let you vote “yes” or “no” on a lottery. ••• Sen. Jim McClendon represents District 11 in the Alabama Senate, which includes all or parts of Talladega, St. Clair, and Shelby counties. You can reach his Senate office at 334-242-7898 or email him at jimmcc@windstream.net

Jim McClendon to introduce Alabama Lottery bill in special session

Alabama could be getting a state lottery soon, with the money going to fund Medicaid and schools statewide. State Sen. Jim McClendon, a Springville Republican, will be sponsoring a bill for the upcoming special session of the Alabama Legislature, scheduled to meet starting Aug. 15. A study by the nonpartisan Legislative Fiscal Office says McClendon’s lottery proposal could raise as much as $427 million annually. If approved, the revenue would be used toward a projected $85 million budget shortfall for Medicaid in 2017, as well as add $100 million annually for Alabama schools. “It is time to let the people vote on a lottery,” McClendon said in a statement Tuesday. “For thousands of families and children, the Medicaid budget shortfall is a personal crisis that we must solve now. “This lottery proposal will resolve the Medicaid problem and inject $100 million annually in new funding for our classrooms.” The bill would authorize Gov. Robert Bentley to negotiate a compact with the Poarch Creek Indians, and allow electronic lottery terminals in Birmingham and Mobile, as well as Macon and Greene counties. There would also be a bond issue based on expected revenue from the lottery, estimated at $75-85 million, to help close Medicaid’s 2017 budget gap. “Every year, thousands of Alabamians drive to neighboring states to play lotteries,” McClendon added. “That is money that should stay right here in our own state, to fund Alabama’s hospitals and schools. “And let me dispel a persistent myth: creating a lottery will not open the door to casino gaming. There is not one single instance in the United States where creating a lottery opened the door to legalizing gambling.” To be included on the November ballot, a lottery bill would have to pass by Aug. 24. Final approval will then be up to voters. “We must once and for all solve problems that have held our state back for decades. The state of Alabama has not and cannot at this time pay for the most basic services we must provide to our people,” Bentley said in a video message posted on social media July 27. “I am asking that each legislator allow the people back home the right to vote on a statewide lottery. I have faith in the people of this state to make the right and the best choice. I trust the voters and our legislators must do the same.”

Del Marsh says Alabama lawmakers polled on lottery legislation

According to Alabama Senate President Pro Tem Del Marsh, Alabama lawmakers are being polled regarding their support for lottery legislation as Gov. Robert Bentley contemplates a special session of the Alabama Legislature later this summer or in early fall. Last week Bentley announced he’s still considering a special session to make up a shortfall in the state’s Medicaid funding — which fell short of the agency’s requested budget by $85 million — and that he anticipated an announcement soon on whether he would call said session. In the spring, lawmakers funded up to $700 million for Medicaid. The program requires at least $785 million to operate. A state lottery could potentially fund the budget shortfall. Several lawmakers have lottery bills in the works, including Gadsden-Democrat and House Minority Leader Craig Ford and Springfield-Republican Sen. Jim McClendon. Earlier this year, other lottery bills stalled in the Legislature under a mix of opposition to gambling, disagreements on how a state lottery should be structured and a push to include casino gambling. The bills failed to receive a floor vote in either chamber. Forty-four states have lotteries. Alabama is one of only six states without one, along with Mississippi, Utah, Nevada, Hawaii and Alaska. The state last considered a lottery in 1999, under Gov. Don Siegelman, when it was voted down.

Daniel Sutter: The Medicaid match game

America spends around $500 billion annually on Medicaid, the government health insurance program for the poor and disabled. Despite this expenditure, Medicaid delivers poor coverage and medical outcomes for low-income Americans, as I discussed last time. Fortunately, reform offers the potential to curb spending and improve the quality of care. Medicaid is a joint state and federal program, with states operating programs under federal rules. Washington provides around 60 percent of the funding through matching grants, under which every dollar a state spends is matched by Washington. States have different matching rates based on state income. The highest income states get a dollar-for-dollar match, while Mississippi gets about $3 for each dollar spent. Matching grants encourage extra spending. The reason is simple: states only pay half (or less) of every extra dollar spent. Half or more of savings from cutting waste also returns to Washington. By distorting decisions about spending or cutting waste over time, matching grants lead to excessive spending. The important question, though, is what portion of today’s Medicaid spending is attributable to matching grants. Economists have authored numerous studies exploring the causes of the growth of Medicaid. In a study just published by the Mercatus Center, I reviewed these studies for evidence of an impact of the matching grant structure on spending. Differences in spending across states provide the best documentation of the role of matching rates, party politics, and interest group lobbying. But a complication arises. The federal government mandates coverage certain for groups (for example, low-income children and pregnant women) and treatments (like hospitalization), while other groups and treatments are optional. State factors will likely affect only optional spending. Research studies focusing on optional spending do reveal significant effects of party control of state government, the matching rate, and interest groups on differences in spending. The interest group effects provide insight into an otherwise surprising aspect of Medicaid. Although Medicaid is frequently described as for low-income Americans, almost two-thirds of spending is on the disabled and elderly. Many political observers concur the poor are a weak interest group, and they appear to lose out in the competition for Medicaid dollars. States with the best matching grant rate spend more than high-income states, but since all states get at least a dollar-for-dollar match, even high-income states spend more than they might otherwise. This helps illustrate why Medicaid has failed to equalize spending between high- and low-income states, which was the rationale for low-income states’ more favorable match. High-income states secure a large share of federal dollars for themselves by covering optional groups and optional procedures. The Affordable Care Act sought to make adults in all states who earn up to 138 percent of the poverty level eligible for Medicaid, but several high-income states already covered adults beyond this level. Block grants, which fix the level of federal aid to a state for several years at a time, provide an alternative way to distribute money. Importantly, the federal grant does not increase if a state spends more. Block grants encourage responsible spending by having states pay the full cost of optional spending and keep the savings from cutting waste. The idea of replacing matching grants with block grants is not new. Welfare reform under President Bill Clinton involved this change, which has helped check spending growth. Rhode Island has experimented with block grants for Medicaid. Block grants could help direct more federal dollars to low-income states, enabling higher reimbursement rates to doctors and hospitals for Medicaid patients and improve health care outcomes. Adjustment of the block grant amount for changes in the poverty rate or health care inflation can ensure states have extra dollars when a weak economy increases eligibility for Medicaid. Reform is sometimes a code word for cutting government services. But ending the Medicaid match game could help deliver better care for low-income Americans and curb spending growth. ••• Daniel Sutter is the Charles G. Koch Professor of Economics at Troy University and host of Econversations on TrojanVision. His study “The Political Economy of Medicaid Expansion: Federalism, Interest Groups, and the ACA” is available at https://mercatus.org/

8 Reasons Rick Scott is the perfect veep for Donald Trump

Rick Scott is basically as awful as Donald Trump in so many ways. But before Floridians start petitioning Trump to introduce Scott to a presidential election turnout and an embarrassing loss before Scott runs for U.S. Senate in 2018, read all eight reasons. 8) Cons. Scott didn’t build his $300-some million fortune with a fraudulent university, but he did help build a company that defrauded Medicare and Medicaid by way more, paying a record $1.7 billion fine. 7) Muslims. Scott was offending Muslims and Hispanics long before Trump descended down the escalator at Trump Tower. Scott put some of his first campaign dollars into fear mongering about Muslims in “Obama’s Mosque” near Ground Zero in 2010. Also, mic cut. 6) Hispanics. Similar to Trump, and despite all evidence, Hispanics love Scott, according to…only Rick Scott. Scott claims he “won” the Hispanic vote in 2014, despite actually losing it by 20 percent. 5) Little Marco. While Trump’s insults are infamous, Scott is doing his part in Florida. He backed Trump over Rubio (and Jeb!) and is now working against Rubio in his US Senate race, supporting mini-Trump Carlos Beruff, best known for unapologetically calling President Obama an “animal.” 4) Smarts. Trump could own Anderson Cooper‘s “RedicuList” segment, but Scott once got on it for insulting “everybody’s intelligence” trying to defend himself for using on-duty cops at campaign events. 3) Votes. Trump needs turnout to be as depressed as Jeb! after South Carolina. Scott has been hard at work, rolling back civil rights reforms that allowed nonviolent, ex-felons to vote. 2) Money. Scott won in 2014 by outspending his opponent on TV by $33,000,000. Romney lost Florida by less than 1 percent in 2012, but only outspent Obama by $17 million. An extra $16,000,000 million might have bought 29 electoral votes. 1) Florida. Trump can’t win without Florida, and Rick Scott knows how to win here. ___ Kevin Cate owns CATECOMM, a public relations, digital, and advertising firm based in Florida.

Daniel Sutter: Medicaid fails the poor

This year’s biggest state budget fight involved funding for Alabama Medicaid. The legislature overrode Governor Robert Bentley’s veto to pass a General Fund budget with almost $100 million less in funding than the governor requested. Budget fights over Medicaid should come as no surprise, as it is the largest item in Alabama’s General Fund budget, even though we decided against the Affordable Care Act expansion and have very strict eligibility conditions for poor adults. I recently completed a study for the Mercatus Center at George Mason University on the sources of growth of Medicaid over the past 50 years. Perhaps the most revealing thing I learned while conducting this study is how dramatically our enormously costly Medicaid system fails America’s poor. Medicaid and Medicare were established in 1965 as part of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society to provide health insurance for the poor, disabled, and elderly. Both programs I think were the inevitable product of earlier policy decisions tying health insurance to employment. Employer-paid benefits were not treated as taxable income for employees, strongly encouraging employers to offer health insurance to employees and their families. But this also left persons without jobs without insurance, creating the need for government insurance for the retired, disabled, and poor. Although Medicaid is commonly described as insurance for low-income children and adults, almost two thirds of total spending is for the disabled and elderly. States accomplish this in part by underfunding care for low-income recipients. Medicaid features the lowest reimbursement rates for doctors and hospitals for covered treatments of any insurer, including Medicare. In addition, billing Medicaid is lengthy and time-consuming for healthcare providers. Not surprisingly, doctors try to avoid Medicaid patients; one third of doctors would not accept new Medicaid patients in 2011-12. Medicaid patients often face long waits when able to schedule appointments. The problem is widely recognized. Oregon Senator Ron Wyden once called Medicaid a “caste system” limiting the access of poor Americans to the health care they desire. Health economist Robert Graboyes notes that, “For low-income Americans, Medicaid yields poor coverage, poor care, and poor medical outcomes.” How bad are these outcomes? A University of Virginia study found that Medicaid patients had higher in-hospital mortality, longer hospital stays, and higher costs, controlling for age and other risk factors, than patients with private insurance, Medicare, and even the uninsured. Other studies from leading universities find similar results. Medicaid recipients also use emergency rooms more frequently because of the difficulty they experience scheduling appointments. Affordable Care Act proponents hoped that expanded insurance coverage would reduce healthcare costs by getting patients to see doctors before their health worsened and they went to emergency rooms. Medicaid’s inadequate reimbursement rates thwart this hope. Why does Medicaid deliver so little for low-income Americans? One factor is what I’ve previously called in this column the “spend but don’t tax” attitude among politicians. “Tax and spend” politicians want to spend lots of our money on things that they, their constituents, and special interest groups want. Politicians win votes and campaign contributions for the next election by spending our money. Tax and spenders are willing to raise taxes to fund this. Spend but don’t tax politicians want to spend and keep taxes low to score points with fiscal conservatives. These politicians want to have their cake and not pay for it. Medicaid exemplifies the consequences. Politicians take credit for providing health insurance for the poor; we constantly hear that Alabama Medicaid serves one million Alabamians. Most voters are too busy with their lives to take the time to learn how Medicaid fails to deliver its promise. Big government on the cheap is often an election-winning formula for politicians, but costly for America. How the federal government disperses money to states also contributes to the problems of Medicaid, as my study for the Mercatus Center found. Consequently reform could both contain Medicaid’s cost and improve the quality of healthcare for low income Alabamians. I’ll say more about potential reform next time. ••• Daniel Sutter is the Charles G. Koch Professor of Economics with the Manuel H. Johnson Center for Political Economy at Troy University and host of Econversations on TrojanVision. Respond to him at dsutter@troy.edu.

Robert Bentley weighs possibility of legislative special session

Alabama Governor Robert Bentley hinted at the possibility of a Special Session of the State Legislature to make up a shortfall in the state’s Medicaid funding, which fell short of the agency’s requested budget by $85 million. “I have not made a decision on that yet. I met yesterday with my commissioner for Medicaid. You know, there’s some real problems there,” said the governor during a visit to Birmingham Wednesday, adding he has several months left to make his decision. Depending on the breadth of the governor’s call for the special session, any number of measures that were shot down in the Regular Session could be back on the table. Among the issues mentioned by Bentley were the $640 million BP oil spill settlement compromise and a $800 million prison construction bill. The governor, who has been mostly avoiding questions from the media in the last several weeks, also took the time to reiterate to reporters that he believes he has done nothing improper in his alleged relationship with former senior aide Rebekah Mason. It would be the second year in a row with a Special Session, should the governor follow through with his threat to call one. Meanwhile, a special legislative committee is currently investigating the claims made against Bentley in the articles of impeachment filed during the legislative session. Impeachment of the Governor is one of the few mechanisms through which the Legislature can call itself into session. Should that happen, and the House pass the articles of impeachment, there is some question on how to adjudicate the issue in the Alabama Senate. Under normal circumstances, the hearings would be presided over by the chief justice of the state’s Supreme Court, but Chief Justice Roy Moore was suspended this week by the Alabama Judiciary Inquiry Commission for his attempts to block gay marriage following the U.S. Supreme Court ruling.

Advocacy coalition says it’s time for Alabama to get serious and stop the Medicaid cuts

A bill that would allow Alabama to spend the $20 billion BP oil spill settlement and help fund the state’s $85 million Medicaid shortfall died in the state Senate late Tuesday night. The Legislature’s 30-day session is poised to end Wednesday and lawmakers have yet to find a way to fund the Alabama Medicaid Agency with the additional monies officials say are needed to maintain services across the state for the nearly one million Alabamians who live below the poverty line. Progress seemed to be made last week when the House approved a bill dividing the settlement money to pay off state debts and as well as road projects in coastal Alabama counties, meanwhile freeing up $55 million of the necessary $85 million for the state’s Medicaid program. But the bill stalled in the Senate’s budget committee Tuesday, leaving little hope for closing the budget gap before the Legislature goes out of session. Following Tuesday night’s impasse, Alabama Arise, a coalition advocating for low-income Alabamians, called on the Alabama Legislature and Gov. Robert Bentley to “get serious” and stop the Medicaid cuts. “Putting health care at risk for children, seniors, and people with disabilities is no way to build a stronger Alabama,” said Alabama Arise state coordinator Kimble Forrister. “Neither is lurching from one budget crisis to another because of our state’s failure to solve the General Fund’s long-term funding shortfall. “Alabama’s looming Medicaid cuts would be devastating for our most vulnerable neighbors. The cuts could prompt many pediatricians to leave the state and could end coverage of essential services like outpatient dialysis and adult eyeglasses. “The governor and the Legislature need to act quickly to prevent these Medicaid cuts from becoming a reality later this year. And our state needs to get serious about raising the long-term, sustainable new revenue needed to invest in a healthier, stronger Alabama for all.”

Alabama House passes 11th-hour Medicaid funding patch in BP settlement compromise

A deal providing $70 million in additional funding from the BP settlement to Medicaid was struck Thursday night in the Alabama House, providing a one-time patch to the ailing health care program on the last possible day to come to a compromise during the 2016 Regular Session. Passing the House 82-12, the band-aid measure will come from the more than $1 billion in settlement funds from the 2010 Deepwater Horizon BP oil spill. The settlement isn’t paid in a lump sum, but is spread out over the next 17 years. But the Medicaid patch is not the only part of the grand compromise. Under the agreement, a $600 million bond would be taken out against the promise of the settlement, and used to pay back $448 million in debt obligations and $191 million in infrastructure funding to Mobile and Baldwin Counties, in addition to the funds going to Medicaid. The $70 million Medicaid money is still $15 short of what the agency requested, and has detractors on both sides of the issue. Ed Henry, Republican of Hartselle and other legislators and interested parties are concerned this amounts to kicking the can down the road once again. “What I do hate is the idea of spending one-time money on Medicaid,” said Henry. The Senate left their record open to receive messages from the House, ensuring the compromise can be taken up by the upper body in the last two days of the Regular Session. Both the House and Senate are adjourned until Tuesday. They are expected to reconvene Tuesday, and conclude the year’s session Wednesday.

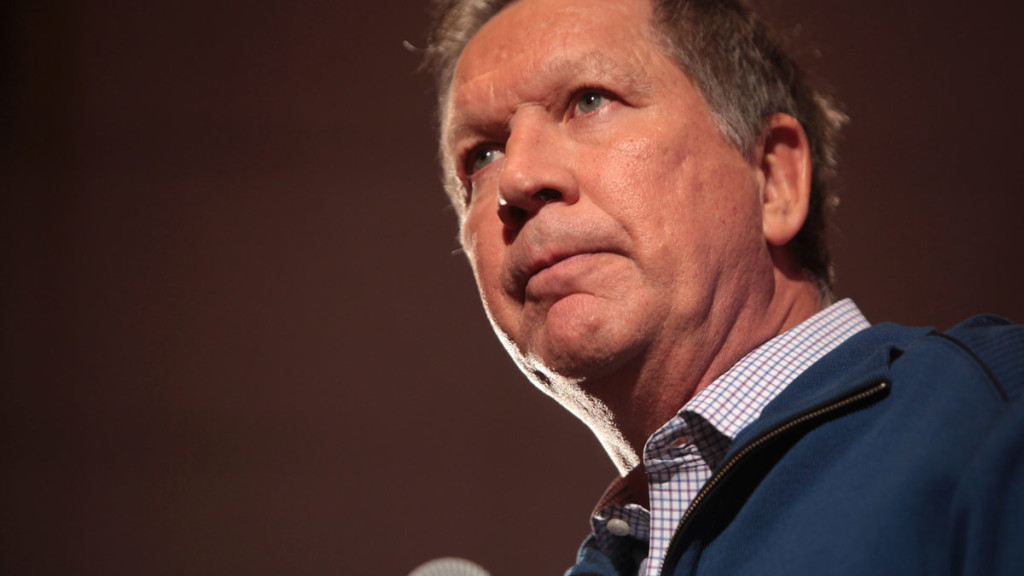

Obamacare roadshow: Watchdog covers the cost of John Kasich’s Medicaid expansion

Ohio Gov. John Kasich’s poll numbers may not be skyrocketing, but the cost of expanding Medicaid in his state certainly is. For Watchdog readers, neither of these things will come as a surprise. When Kasich announced his bid for the presidency last year, Watchdog’s coverage of his major policy decisions as governor of Ohio had already been nearly a year in the making. Since then, Kasich’s presidential campaign has brought his controversial decision to take advantage of President Obama’s unpopular 2010 healthcare law into the spotlight as Republican primary voters decide whether the Ohio governor’s policies align with their values. Kasich’s Obamacare expansion Watchdog reporter Jason Hart first took up the story in September 2014. Ohio’s Medicaid enrollment under the expansion had just topped 367,000, passing Kasich’s initial projection for enrollment levels at July 2015. In the year and a half since, the governor’s projections for his state have continued to fall far short of the actual tally. Last March was the most expensive month yet for the expanded program, costing taxpayers $411 million as more working-age adults with no kids and no disabilities flocked to the Medicaid rolls. This puts Kasich’s Obamacare expansion on track to cost $28.5 billion by the year 2020 – more than twice as much as his administration projected. This has raised questions from critics who worry that expanding health care for able-bodied adults could be a disincentive to work. How many of the Ohioans who have recently enrolled in Medicaid have jobs? No one knows, not even the Ohio Department of Medicaid. Last Spring, the department told state Senate members that 43 percent of enrollees were employed, but it has no current data on how many of Ohio’s 673,000 Obamacare expansion enrollees are gainfully employed. ODM also doesn’t track how many of these new enrollees had private or employer-sponsored health insurance prior to enrolling in Medicaid – or how many of them are incarcerated. Never mind that Kasich initially estimated 447,000 people would sign up under the expansion by 2020. That means that “if ODM capped Obamacare expansion enrollment at its current level,” wrote Hart, “the two-year-old program would already be 48 percent larger than the Kasich administration said it would be after seven years.” Lest anyone be confused about how Medicaid expansion became part of Ohio law in the first place, Hart has a helpful breakdown of how the policy fight played out in 2013: The Ohio House stripped the Obamacare Medicaid expansion from its version of the 2014-15 budget. The Ohio General Assembly explicitly banned expansion in the final 2014-15 budget sent to Kasich’s desk. Kasich used a line-item veto to strike the legislature’s ban on expansion. The Kasich administration, with approval from the Obama administration, expanded Medicaid to the guidelines set in Obamacare. The Kasich administration asked the Ohio Controlling Board to appropriate funding to pay for the Medicaid expansion. The Ohio Controlling Board approved Kasich’s Obamacare expansion funding request. Six Republican legislators and two Right to Life groups sued over Kasich’s Controlling Board maneuver, but the Ohio Supreme Court ruled in the Kasich administration’s favor. Read the rest of this article here. • • • This article originally appeared at Watchdog.org. Andrew Collins is an author at the Franklin Center for Government and Public Integrity.