Parker Snider: Understanding Constitutional Amendment One – The Ten Commandments and Religious Freedom

For years, discussion over the public display of the Ten Commandments has animated Alabama’s political landscape. The issue is so energizing, it seems, that many politicians frame their own races through the lens of this battle––that support for their candidacy is a vote for the Ten Commandments. Even so, Alabamians have never actually gotten a chance to vote directly on the issue. This November, however, a constitutional amendment sponsored by Senator Gerald Dial provides that opportunity. Statewide Amendment 1, if successful, would enshrine in the state constitution language signifying two things, a) that the Ten Commandments is authorized to be displayed on public property, including public schools and b) that no person’s religion can affect his or her political or civil rights. This amendment, as expected, has received its share of support and criticism. Dean Young, Chairman of the Ten Commandments PAC, suggests this to be a vote where Alabama decides if we “want to acknowledge God”. He also remarks that we will be held accountable for our vote on judgment day. Not all Christians agree with Young, however. The Baptist Joint Committee, for example, argues that “the government should represent all constituents regardless of religious belief” and not involve itself in “religious favoritism”. The question, of course, is of the real impact of this amendment. Essential to the discussion of impact is one provision within the amendment that may be easily ignored: the fact that any Ten Commandments display must comply with constitutional requirements. This provision explicitly acknowledges that Ten Commandments displays in Alabama are subject to the U.S. Constitution, and therefore the U.S. Supreme Court. The U.S. Supreme Court, it is important to note, has largely settled on an understanding of the constitutionality of this issue through three precedent-setting court rulings. In McCreary County v. ACLU, the Supreme Court ruled that the display of the Ten Commandments in a Kentucky courthouse was unconstitutional. In Van Orden v. Perry, however, the Court allowed the Ten Commandments to be displayed, provided it was within a larger array of historical monuments and markers. In regard to the display of the Ten Commandments in public schools, the Court ruled in Stone v. Graham that posting the Ten Commandments in every public school classroom, as required by a Kentucky law, served “no secular purpose” and was therefore unconstitutional. As this amendment is subject to these precedents and already-existing First Amendment protections, the approval or rejection of this amendment will likely have limited immediate impact in Alabama. What, then, is the purpose? In a recent call with the Alabama Policy Institute, Senator Dial––the sponsor of the amendment–– answered that question. He acknowledged that, for the amendment to have greatest impact, the U.S. Supreme Court will have to rule differently in the future. Senator Dial also offered another reason to support the amendment. He remarked that this amendment would shift liability from the individual or government office displaying the Ten Commandments to the state. The hope of this amendment is to embolden displays of the Ten Commandments under the legal protection of the state constitution, Dial suggests, and to let the state deal with any legal ramifications. It is important to mention, however, that the amendment specifies that no public funds can be used to defend its constitutionality. If there are legal challenges, Senator Dial suggests that a third party will fund the defense. To be sure, this amendment brings yet again to the public eye an issue that some consider settled. The Supreme Court precedent will––new rulings notwithstanding––supersede any constitutional amendments the people of Alabama pass or fail to pass on the subject. If the U.S. Supreme Court were to, however, overturn past precedent, the success or failure of this amendment could be consequential. ••• Parker Snider is Policy Relations Manager for the Alabama Policy Institute (API). API is an independent, nonpartisan, nonprofit research and educational organization dedicated to strengthening free enterprise, defending limited government, and championing strong families. If you would like to speak with the author, please e-mail communications@alabamapolicy.org or call (205) 870-9900.

Parker Snider: Prepare to vote on constitutional amendments, Alabama

The drought, as they say, is over. Football season is back in Alabama. To no one’s surprise, the Alabama Crimson Tide was ranked #1 in both the AP and Coaches preseason polls. Almost simultaneously as the return of college football, however, is the beginning of another all-too-familiar season for Alabamians. That season, of course, is election season. In this season, as in the college football season, Alabama earns a number one ranking. This ranking isn’t for being the state with the most elections, however. No, this additional #1 ranking is for our massive state constitution, the longest constitution in America and, perhaps, the world. Our constitution is well over 300,000 words–that’s forty times longer than the U.S. Constitution. The only governing document that rivals the size of Alabama’s is that of India, although it is still less than half as lengthy. Our constitution’s depth, it seems, is due to the 928 amendments that have been added since the constitution’s inception in 1901. Although some amendments are substantive and generally applicable to the entire state, a large portion of the amendments only deal with a singular county. This is because the Constitutional Convention of 1901, in an effort to regain control of the state after Reconstruction, concentrated power so heavily in Montgomery that many local decisions were, and still are, not legally permitted without an explicit change in the constitution, e.g. a constitutional amendment. This means that anytime a county wants to, for example, levy a minor tax, institute local term limits, or create a toll road, a constitutional amendment is required. In November, Alabamians will have the opportunity to make the state constitution even longer. This year, residents will vote on four statewide constitutional amendments, a relatively small number in light of the fourteen voted on in 2016. Included on the ballot will be constitutional amendments concerning the public display of the Ten Commandments, abortion, the University of Alabama’s Board of Trustees, and special elections for legislative vacancies. Although it is easy to treat constitutional amendments as an afterthought (they are, in fact, at the end of the ballot), it is important to understand the potential impact of a change to the state’s most significant document. Unfortunately, the language describing constitutional amendments on the ballot is often difficult to understand. Additionally, there is no description of the effects of a proposed amendment. This can be disheartening to voters taking their voice in the electoral process seriously while at the same time encouraging split-second decisions and absent-minded bubbling. Neither of these cases are desirable. That’s why, in the upcoming weeks, the Alabama Policy Institute will release op-eds on the constitutional amendments in easy-to-understand language, including the possible effects, or lack thereof, on the state. We will also be releasing a one-stop Guide to the Issues that will explain the amendments concisely and readably in a format that can be taken into the voting booth. Stay tuned. ••• Parker Snider is Manager of Policy Relations for the Alabama Policy Institute, an independent, nonpartisan, nonprofit research and educational organization dedicated to strengthening free enterprise, defending limited government, and championing strong families.

Parker Snider: Limited government demands more, not less, of Alabama

In Alabama, politicians and residents alike proclaim the benefits of limited government. Appropriately, our state’s motto is Audemus jura nostra defendere, which, when translated into the more popular language of English, reads “We dare defend our rights”. The phrase in original context––an 18th century poem by Sir William Jones––is followed by the potential thief of rights: “the tyrant while they wield the chain”, i.e. the government. Promoting limited government, evidently, is woven into what it means to be ‘Alabama’, and rightly so. Public office holders, candidates, and voters regularly point to the necessity of a limited government, as it is through limited government that our freedoms remain intact. What is not as often discussed, unfortunately, is that smaller or limited government requires larger voluntary community engagement. This is true because there will always be gaps where government could arguably be active. Limited government, by definition, means that there will be some spaces, some needs or hopes of the community or community members, that are not met by a central power. In states that don’t deem limited government as a highly as Alabama, these gaps tend to be filled by government. In a state like Alabama, however, these spaces are befittingly left to be filled by the private sector. The duty, therefore, of community members to selflessly and actively consider others is higher in a state that prioritizes limited government than in one that does not. Alabama, regrettably, yields ample problems that need innovative, community-based solutions. For example, metro Birmingham, the state’s primary economic powerhouse, is growing at a much more modest rate than peer cities like Nashville in terms of GDP and employment. A report by the “Building (It) Together” campaign also mentions that the metro area is losing workers while most peer cities are not. Obviously, these are problems if the state wants to thrive economically in the future. There, of course, are a variety of contributing causes to this economic underperformance, both in Birmingham and across the state. In order to address some of these underlying issues––and in light of our understanding of the responsibility of the private sector––the Alabama Policy Institute is participating in a community initiative we call Hiring Well, Doing Good. In short, Hiring Well, Doing Good takes aim at one of the systematic problems facing our state: chronic unemployment. Through working with community organizations including non-profits, foundations, and employers in the state, API plans to connect the chronically unemployed with training opportunities, professional development, and––ultimately––long-term employers. Our hope is to be a small part of solving the issues facing the Birmingham metro and Alabama as a whole. Regardless of what API is doing, the principle stands. Stalwarts of limited government must remember that limited government demands more, not less, of Alabama. ••• Parker Snider is Manager of Policy Relations for the Alabama Policy Institute, an independent, nonpartisan, nonprofit research and educational organization dedicated to strengthening free enterprise, defending limited government, and championing strong families.

Parker Snider: Charter schools are keeping promises

On the campaign trail in 2012, Mitt Romney remarked that “charter schools are so successful that almost every politician can find something good to say about them.” Romney was right. President Bush told crowds he was a “big believer” in charter schools, President Obama proclaimed National Charter Schools Week year after year, and 2016 presidential candidates Bernie Sanders, Donald Trump, and Hillary Clinton are all on record praising public charter schools. From 2016 to 2017, however, support for charter schools dropped a startling 12 percent, from above 50% to below 40%, according to a 2017 EdNext poll. Interestingly enough, the decrease was equal for both Democrats and Republicans. One reason for falling support is likely an increased public awareness of the failures of some charter schools and charter school executives. In 2016, documented cases of charter school executives turned criminals hit the airwaves in multiple states. Additionally, reports of charter schools suddenly closing, leaving students to fend for themselves in the middle of the school year, have made headlines and been the subject of many op-eds in national newspapers. It’s easy to see why these public failures might quell support for charter schools. Truthfully, however, across the nation and in Alabama, many charter schools are fulfilling their promises. For example, KIPP, the nation’s largest non-profit public charter school network with over two hundred schools, sees a majority of its students outpacing national growth averages. Additionally, most KIPP schools are outperforming the traditional public schools in their districts. Although there are no KIPP schools in Alabama, Sumter County’s new University Charter School opened its doors last Monday. As described in Trisha Powell Crain‘s AL.com article, the mission of UCS is to integrate the community while providing a high-quality education. UCS is on its way towards achieving that mission. Contrary to county tradition, UCS boasts a student population that is about half black and half white. Before UCS, the schools in Alabama’s poorest county were still segregated, decades after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that separating white and black children in different schools was unconstitutional. Although charter schools are few and far between in Alabama (only five have been approved since charter school legislation made them possible in 2015), the strides that University Charter School has made for its community should encourage more districts to pursue innovative ideas for their school systems. Innovative ideas include charter schools, of course, but NBA superstar LeBron James‘ I Promise School in Akron, Ohio – a public non-charter school that is a partnership between the I Promise Network, the LeBron James Family Foundation, and Akron Public Schools – proves that solutions to education woes can come in many forms. Regardless of the specifics, Alabamians should be thankful for the good that charter schools and other innovative education options have created for students across the country. We must not, however, neglect to learn from the failures of schools in other areas. Alabamians should work, therefore, to replicate those innovate solutions that are successful, as University Charter School is doing, here in our state. ••• Parker Snider is Manager of Policy Relations for the Alabama Policy Institute, an independent, nonpartisan, nonprofit research and educational organization dedicated to strengthening free enterprise, defending limited government, and championing strong families.

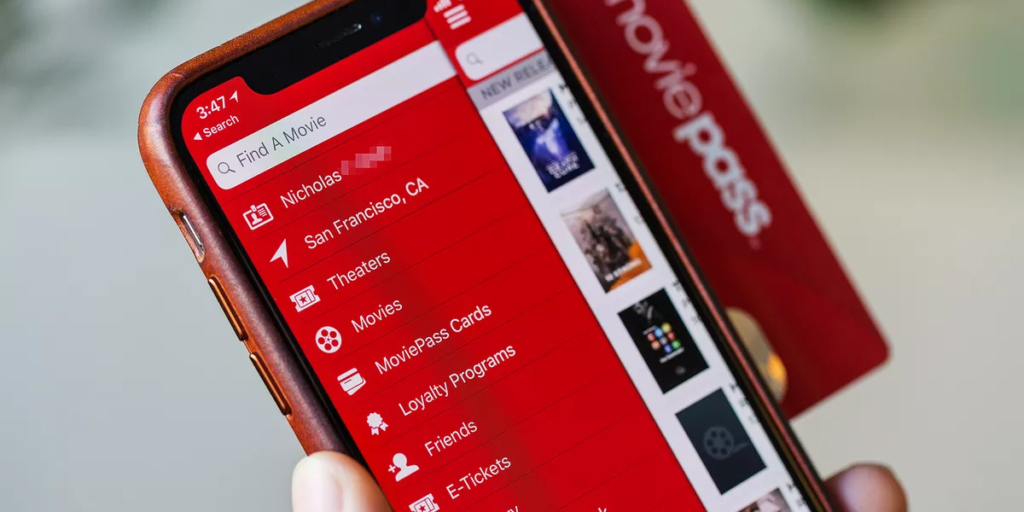

Parker Snider: Learning fiscal responsibility from the fall of MoviePass

One year ago, a relatively-unknown company announced that, for a monthly fee of $9.95, subscribers could see one movie a day without paying anything at the box office. That’s right – even though the average movie ticket in the U.S. is $9 – a $9.95 monthly subscription could get you into 31 movies. Since last August, three million film-goers have subscribed to MoviePass, the company offering this seemingly too-good-to-be-true service. Profitability aside, the service worked. Many subscribers did, in fact, see movies day after day. Blockbusters like the 8th Star Wars film were viewed repeatedly by fans and, as loyal subscribers became the most company’s most potent salesmen, MoviePass’ subscription rate skyrocketed. Things didn’t stay rosy forever, though. The weekend before eventual $2 billion-earner Avengers: Infinity War hit theatres in late April, MoviePass conveniently announced that they would no longer allow repeat viewings of one movie. This was the beginning of the end. In the weeks following, MoviePass declared a slew of changes to their service, including blackouts of popular movies and surcharges to other films that, at times, were more expensive than buying a ticket without MoviePass (i.e. an $8 surcharge for a $5 movie). In late July, MoviePass subscribers found the system unavailable and customer service unresponsive. The company, as expected, finally ran out of cash. Although MoviePass was able to secure another loan to stay above water, the company’s future is in serious doubt. As of publication, the stock of MoviePass parent company Helios & Matheson Analytics is trading at a lowly $0.07. The best way to learn, some say, is from failure. Alabama residents and lawmakers alike, therefore, should learn from the demise of MoviePass. The lesson? The importance of fiscal responsibility. Fiscal responsibility first demands a healthy sense of realism. MoviePass lacked realistic expectations and now needs another “another $1.2 billion”, according to CNN. The truth is that our public policy discussions are full of MoviePass-like hopes: ideas that are well-intentioned but simply lack realistic expectations. A system of government-sponsored “basic income”, in which residents receive generous sums of money for living expenses, is one recent example of this type of idea. Fiscal responsibility also requires honesty. Unlike MoviePass’ perhaps-knowingly deceptive relationship with its customers, policy-makers with accurate understandings of finance and economics must be honest – off and on the campaign trail – about the financial viability of certain public policies. Lofty campaign promises made in full view of a different post-election reality do nothing but increase expectations and, when these expectations aren’t met, decrease trust in government. The problem is that, like MoviePass, giveaway ideas like these become popular fast, and often for good reason. These proposals are hopeful, compassionate, and promoted by people who genuinely believe they will work. Often, however, the “how” gets ignored, those who understand the likelihood of failure stand silent, and the project collapses. Instead of giving credence to unrealistic and unlikely proposals, Alabama residents and lawmakers should realistically and honestly engage public policy ideas that have the potential to succeed, not just for an official’s time in office, but in the long run. These ideas may be not be as dramatic or fashionable as MoviePass, but they just might work. ••• Parker Snider is Manager of Policy Relations for the Alabama Policy Institute, an independent, nonpartisan, nonprofit research and educational organization dedicated to strengthening free enterprise, defending limited government, and championing strong families.

Parker Snider: Seeing the power of compassion, hope, and work first-hand

Three years ago, I had the privilege of visiting South America for the first time. During my stay, I—along with the rest of my group—met a family whose story broke our hearts. Led by a single mother, the family lived in an aluminum-roofed and mud-filled house in the middle of a village town square, right between two churches. Her adult children still lived with her in their home: one blind and two deaf, blind, and intellectually disabled. Their abusive father abandoned them long ago. The government cared little about these rural people. The two churches, within spitting distance, never troubled themselves with the family. They were, by many standards, forgotten. Thankfully, however, our local partner became aware of this family and determined a way that we, temporary visitors, might make a lasting impact. Through some South American creativity and a lot of bamboo, we were able to make their lives easier, safer, and cleaner. We left feeling tired from work yet restless to know our effectiveness, discouraged by their past yet hopeful for their future. This June we returned to the family’s home. Our arrival was met not with the timid greetings of before but with a new and palpable joy. To my surprise, present at the home was not only the family, but a host of other community members. I was eager to see whether our work had been successful, and the locals were eager to show us that it had, in fact, not been in vain. Just as exciting for me to see was that out of this home now grows a small business. Together with the community, members of the family weave and sell baskets (which we were more than happy to purchase). A lot has changed since our first visit. I cannot be sure exactly why, but I have some ideas. First, I trust that being shown God’s love, not only through our initial visit but through the presence of many others over the years, has reminded them of their worth. Second, I am confident that having certain urgent physical needs met has instilled a hope that their future may be better than their past. Third, I believe that working, for however long, has provided a sense of dignity. This transformation in a South American village offers principles that we must remember as we seek community renewal in the United States. First is the fact that struggling Americans need to be reminded of their value as much as this South American family. We often, intentionally or not, strip people of their God-given worth when we reduce them to whether they receive government support or not. The truth is that, regardless of wealth or status, all people are infinitely valuable. We ought to recognize and exemplify this reality regularly. Only when our compassion is felt and truly experienced by those facing difficulties, specifically the unemployed, will our oft-heralded advice to pursue the dignity of work—the second principle the South American family’s transformation reveals—be received. Work has always been part of God’s design for humanity. In the very beginning, even before the curse of sin, God placed Adam “in the garden of Eden to work it and keep it” (Genesis 2:15). John Piper writes that “God made us to work. He formed our minds to think and our hands to make. He gave us strength—little or great—to be about the business of altering the way things are.” Therefore, we must promote work not because we’re sick of supporting others, but because we trust that God’s plan for humanity’s good is for us to work, and to work hard. Witnessing the change of this family is just one of many formative and equally (if not more) incredible experiences from my time in South America. Most of these were, of course, more personal. This family’s transformation, however, demonstrates general and essential truths that we would do well to remember—namely the power of compassion, hope, and work. ••• Parker Snider is Policy Relations Manager at the Alabama Policy Institute (API). API is an independent, nonpartisan, nonprofit research and educational organization dedicated to strengthening free enterprise, defending limited government, and championing strong families. If you would like to speak with the author, please e-mail communications@alabamapolicy.org or call (205) 870-9900.

Parker Snider: Monopoly and locksmiths

I love the game of Monopoly. The hope that I will land on expensive properties first, the poker-esque bluffing, and the art of deal-making with unsuspecting friends makes for a great game night. Even though I love Monopoly, I don’t always enjoy it. When I’ve missed out on important properties and am mortgaging the few I have left to pay the winner, I’m not having any fun. When it’s obvious I will not win and I slowly move from competitor to benefactor, I’m not thankful and neither are others facing a similar end. I think this distaste says something obvious: Monopoly is great for the winner. Crowding out competition and increasing prices because you have the power to do so is good sport for the already-powerful, yet detrimental to the mobility of others. Monopoly is predicated on our tendency towards self-preservation and self-centeredness. This tendency, utilized for recreation in Monopoly, is manifested in Alabama through our occupational licensing laws (also known as permission-slip-to-work laws). Take locksmiths, for example. Established in the late 1990s, the Alabama Electronic Security Board of Licensure regulates both security alarm installers and locksmiths. Not a big deal, right? Wrong. Wrong because Alabama is, as shown in a recent report, one of only 15 states that licenses locksmiths. Wrong because being in such a minority mandates we ask, “Why do we license locksmiths in the first place?” Robert Burns describes his experience as a locksmith in a video recently published by the Alabama Policy Institute. In it, he suggests that the licensing of locksmiths was established in Alabama to protect the power of practitioners – not the safety of the public – and that it makes becoming a locksmith more difficult than necessary. Before any Alabamian can work as a locksmith they must pay fees, pass tests, and wait to be approved by the government. In most of the country, these hurdles are nonexistent and residents hoping to work as a locksmith can do so when the private sector (through employers and training), not the government, deems appropriate. In Alabama, however, tendencies that should be reserved to a board game—tendencies to concentrate power towards ourselves and restrict competition—have been allowed into our occupational licensing structure. We must make every effort, therefore, to identify where licensing exists only to disincentivize entrance into a profession and to eliminate regulations where necessary. ••• Parker Snider is Policy Relations Manager for the Alabama Policy Institute (API). API is an independent, nonpartisan, nonprofit research and educational organization dedicated to strengthening free enterprise, defending limited government, and championing strong families. If you would like to speak with the author, please e-mail communications@alabamapolicy.org or call (205) 870-9900.

Parker Snider: State elections matter more than most think

Washington, D.C.—one of the most visited cities in the world—oozes a sense of superiority and power. How could it not? Our nation’s Capitol building is truly enormous, the Secret Service and Capitol police carry rifles regularly, and the President of the most powerful country in the world lives within its borders. Anyone, whether a visitor, summer intern, or permanent resident, feels that they are amongst the most formidable and important people in the world when in Washington. This sentiment is mostly true. The President, Congress, and Supreme Court do yield great authority and power to influence our lives—if they choose to use it. The truth, however, is that state governments are more likely than the federal government to create laws and policies that affect our day-to-day lives. This is, in fact, how our country was designed. James Madison, a founding father and our fourth President, wrote in Federalist No. 45 that “the operations of the federal government will be most extensive and important in times of war and danger; those of the State governments, in times of peace and security.” In layman’s terms: the federal government will protect our national security and borders while the states dictate domestic policy. Admittedly, Madison’s vision of federalism is not exactly what we see today, as the federal government often rules like it is “most extensive and important” in both peacetime and wartime. Even so, the 10th amendment of the Constitution remains, and all powers not delegated to the federal government are constitutionally reserved to the states. Although the federal government finds itself at a standstill arguing about all types of domestic policy, state governments are productively creating them every day. Take, for instance, the Alabama legislature. In the first three months of 2018, the Alabama State House and Senate passed over 300 bills. The U.S. Congress, with all its power and superiority, has passed only 172 bills since the beginning of last year. This gap is even more pronounced when examined nationally. In 2014 alone state legislatures passed over 24,000 bills. The 113th Congress, by contrast, passed only 296 bills in both 2013 and 2014. This productivity gap is largely because, unlike in Washington, many states have supermajorities of a singular political party. This makes it immensely easier to pass legislation in the states. These laws, although restricted to a single state, are not limited to minor issues. During the Obama administration, for example, states enacted over 200 restrictions on abortion. State governments are also in charge of public education, determine how to tax their residents, and decide infrastructure spending—spending that could easily impact your daily commute. State governments also recruit businesses and jobs to the area, determine many welfare benefits and qualifications, regulate occupations (for better or for worse), and draw their own district lines. The reality is that the actions of the state government can have immediate and consequential effects on our everyday lives. This makes it critically important to know the candidates we are voting for in state elections. The days of the national media covering Alabama politics constantly are, for the moment, over. Fox News and CNN aren’t reporting on our governor’s race like they did last year’s race for U.S. Senate—and they certainly are not following our races for lieutenant governor, attorney general, or those of other down ballot positions. Alabamians, therefore, must intentionally learn about the candidates, their records, and their positions. Thankfully, there are ample opportunities to do so including recorded debates, coverage by local news organizations, and detailed policy questionnaires. On June 5th, Alabamians will vote. When we do, we must not vote blindly based off name recognition or slick advertising. We should, instead, learn about candidates up and down the ballot because state elections matter more than most think. ••• Parker Snider is Policy Relations Manager for the Alabama Policy Institute (API). API is an independent, nonpartisan, nonprofit research and educational organization dedicated to strengthening free enterprise, defending limited government, and championing strong families. If you would like to speak with the author, please e-mail communications@alabamapolicy.org or call (205) 870-9900.

Parker Snider: A guide to fake news

More than once every day. That’s how often President Donald Trump publicly calls something “fake”—be it a story, poll, or news organization. Just this week, Facebook CEO and Founder Mark Zuckerberg testified before Congress about, among other things, the proliferation of falsities on his social media platform, including in Alabama’s special election for U.S. Senate last year. We see the term everywhere, hear it lobbied daily on cable news, and use it ourselves (although perhaps often in jest). But what really is fake news and how do we spot it? The term “fake news” is often used to describe three very distinct and separate entities. First, the reporting of reputable national organizations (think press that have a seat in the White House briefing room, especially those in the first few rows) is often labeled as “fake news”. Although many would argue otherwise, the fact is that outright lies by the news divisions of these organizations are rare. When reporting failures do occur, news organizations hold their reporters accountable and publicly apologize and correct the story. The suspension of ABC’s Brian Ross after incorrectly reporting that Trump had directed Michael Flynn to contact Russian officials before the 2016 election is one example. This doesn’t mean, however, that print or televised media are free from falsehoods. They’re not. That’s because newspapers and news channels aren’t just publishing journalism—no, their business requires something else—opinion and commentary, the second bearer of the “fake news” label. Fox News’ Chief News Anchor Shephard Smith isn’t shy about rebutting the unsubstantiated claims of his primetime opinion counterparts. Why? In his words, “We serve different masters.” In his interview with Time, he goes on to say, “They don’t really have rules on the opinion side…some of our opinion programming is there strictly to be entertaining.” Nevertheless, false news and misrepresentation is most onerous and rampant, not on television or in newspapers, but on social media, the third and most appropriately labeled agent of “fake news”. Facebook and its competitors are places where claims, no matter how ridiculous, baseless, and unproven, spread like wildfire. It’s where we see a supposed ‘Friends’ reunion, that President Obama was a Black Panther, that Pope Francis cancelled the Bible, and that Snopes, a useful fact checking website, has ties to George Soros. Even so, Facebook is a major source of news for many people. Thanks to this and increased cries of “fake news”, I’ve found a few practices helpful in maneuvering this volatile news environment. As NPR’s Anya Kamenetz suggests, I begin with a gut check. Does what I’m reading affirm my biases, my hopes, and my expectations? If so, I should adopt a healthy level of suspicion. Second, I automatically reject any news in the form of a meme or screenshot. These easily sharable images often have incendiary captions, outlandish claims, and lack sources. They are designed to go viral—like the emails of yesteryear that promise a free vacation if you simply forward to ten friends—and they are rarely factual. Political memes and screenshots are one way Russians fostered division in 2016, and they are genuinely worthless. Third, I check the source. Does the website, newspaper, or cable news channel have a history of deceptive practices or falsehoods? Are they well-known and given access to government officials, or do they have a strange web address, an unknown name, or a homepage full of inflammatory headlines? Fourth, I look to see if other sources are corroborating the report. If not and the news is a credible exclusive, I expect the reporting organization to include their sources in the article. Fifth, I determine whether the author is a journalist or a commentator. As described earlier, commentators and journalists are very different, as are their standards. Finally, before reposting or sharing, I consider my own credibility. Do I want to be someone who shares unsubstantiated news and memes, or do I want to ensure its accuracy, and therefore my own? I’ve found these methods helpful, and I hope you do as well. ••• Parker Snider is Policy Relations Manager at the Alabama Policy Institute (API). API is an independent, nonpartisan, nonprofit research and educational organization dedicated to strengthening free enterprise, defending limited government, and championing strong families. If you would like to speak with the author, please e-mail communications@alabamapolicy.org or call (205) 870-9900.

Parker Snider: How Christ’s resurrection makes politics better

“He is not here; He has risen!” These are perhaps the most consequential words ever spoken. A man who three days earlier had been violently beaten, hung upon a cross, and buried lifeless in a tomb, is alive again! The reality behind these words—a risen Savior who had borne the sins of the world – prompted the disciples of Jesus to spend their lives spreading this news, Perpetua to die for her faith at the hand of the Romans and, more recently, Jim Elliot to take the still unknown Gospel to the Auca people of Ecuador. Christian heroes from years gone by voluntarily endured suffering, persecution, and death because the Resurrection changed one essential aspect of their being: their hope. The death and resurrection of Jesus, along with His subsequent appearance to more than five hundred witnesses, instills a confidence among believers that there is more than just this world. This confidence, this hope in Christ and the Resurrection, makes politics so much better. We can trust that, no matter who is in charge and what policies are being proposed in Washington or Montgomery, God will have His way. In times like these, this is a relief. Now this doesn’t mean that we can’t fight—we can and we do. It just means that when we fight, we must do so without manipulating facts, exaggerating outcomes, or fear-mongering. The other way, the “by any means necessary” approach, simply doesn’t align with the eternal hope we have as Christians. Since our hope is not in the government or political power, we are free to reject indefensible candidates on our own side, even if doing so might cost us political power. We are free to genuinely listen to those with different opinions, even if they challenge our own, and to praise goodness and truth, no matter the source. Furthermore, we can promote good policy honestly and in a way that is, as the Apostle Paul put it, “above reproach”. When we defend indefensible candidates, reject the validity of those experiences different from our own, scream “Liar!” every time a specific politician opens his or her mouth, or manipulate facts to create a certain narrative, we indicate that our ultimate goal is worldly power. Christians—we must do politics differently. Our faith in the Resurrection gifts us with knowing the ending – that one day all will be made well and we will praise Him for eternity. This knowledge of the future, however, is a luxury that non-Christians do not enjoy. They fight, sometimes “by any means necessary”, as if this world is all there is because, as far as they know, it is. As Christians, we can fight for policies we believe in—and we can fight hard—but, ultimately, our hope is not in politics. It is in the resurrection of Christ and the truth that death, the singular most worried about, written about, and fought against aspect of the human condition, is but a victory to us. This Easter weekend remember, rest, and act confidently in a hope greater than political power in this world—the finished work of Christ. ••• Parker Snider is Policy Relations Manager at the Alabama Policy Institute (API). API is an independent, nonpartisan, nonprofit research and educational organization dedicated to strengthening free enterprise, defending limited government, and championing strong families. If you would like to speak with the author, please e-mail communications@alabamapolicy.org or call (205) 870-9900.

Parker Snider: Alabama’s unrestrained “permission slip to work” laws affect real Alabamians

Across the country, lawmakers are realizing the costs associated with the rampant overuse of occupational licensing laws. Alabama Policy Institute’s recent report shows that over 21% of Alabama workers are licensed. This means that more than one in five Alabamians need a government permission slip to work. Although the original impetus behind states’ licensing practices was the assurance of public safety, the current system of occupational licensing has become so burdensome that voices from left, right, and center have noticed. The Trump and Obama administrations, The Institute for Justice, and the Brookings Institute, among others, are all in agreement: occupational licensing practices need to be changed. The fact is that these laws affect real people – real, everyday Alabamians. Bruce Locke, a retired construction company owner and north Alabama native, is one of those people. A dedicated husband, father, grandpa, and Army veteran, Mr. Locke, after retiring, became an auctioneer. Before he could work, however, Mr. Locke had to pay for state-approved education, apprentice for one year, and hand over hundreds of dollars in fees to the government. He fulfilled the state’s licensure requirements but, after years of being a successful auctioneer, was suddenly fined $500 by the Alabama State Board of Auctioneers. According to the board-hired investigator, Mr. Locke, who had a current license to work, was being fined for not filling out a specific form. The problem, however, is that Mr. Locke, after being a licensed auctioneer for years, had no knowledge of this form. When he asked, Mr. Locke learned that the form was created recently. Even so, he was not told about the form nor given any sort of warning. He was instead fined. Mr. Locke, therefore, under the threat of losing his business, had no choice but to pay the $500 fine. He later, out of frustration and disgust in the board’s apparent greed, gave up his license and sold his business. This is just one example of occupational licensing gone awry. Thanks to occupational licensing, Alabama ran a profitable man out of business, forsaking revenue in both sales and income tax. The truth is, as Mr. Locke put it, “There are a lot of states that do not have auctioneer licenses, and they’re doing just fine.” He’s right. There are twenty states that do not license occupation of auctioneers. In fact, the report found, more broadly, that Alabama licenses thirty-one occupations that are not widely licensed in other states, including locksmiths and sign language interpreters. If it were truly a matter of public safety, one would think there would be relative conformity among the states. The report, however, found that licensing practices are widely varied, even among our neighboring and nearby states. One explanation of this may be economic protectionism – when members of an occupation, in a desire to limit competition, lobby the state legislature to establish licensure. In Montgomery, lawmakers are reviewing legislation that addresses occupational licensing, specifically when it affects military families and veterans. Conservatives should applaud these attempts to curb big government’s grip on citizens while continuing to push for more comprehensive reforms. You can view Mr. Locke telling his story below and API’s recent report on occupational licensing here.

Parker Snider: Increased polarization in politics: bad for Alabama and the country

Our politics is increasingly polarized. Yelling matches on cable news are the norm, and those with opposite viewpoints are labeled as bigoted or anti-American. The division has gotten to the point that, according to the Pew Research Center, most Republicans and Democrats have few or no friends in the opposing party. The question, therefore, is two-fold: a) What are the causes of increased polarization? and b) Is increased polarization something we need to address? I’ll begin with the former. One reason for this increased polarization is that Americans are more often choosing to live among people who are like them politically. Here is an Alabama example of that phenomenon. In 1992, Bob Dole, a Republican, won Marshall County by 15 points. In 2016, Donald Trump’s margin of victory in the county was almost 70 points. Another reason for our increased polarization is the rise of the Internet and social media. While the increased availability of news sources via the Internet is helpful, many choose only to read from sources they agree with politically. The Wall Street Journal offers a tool that allows users to compare the Facebook feeds of people who identify as conservative or liberal. A quick minute or two of comparing the feeds reveals not only the difference between the selection of news, but the frequency of inflammatory rhetoric used to describe people on the other side. Although choosing to live near like-minded people and following conservative or liberal news sources are not inherently bad practices, by doing so we unknowingly create an echo-chamber of group-validation that gives no opportunity for differing opinions. This echo-chamber, with its lack of diverse thought or self-criticism, is a major contributor to increased polarization. So, is this polarization something we need to address? I believe it is. Increased polarization has created antagonistic relationships within our state and country. In our communities, we are bombarded with rhetoric that describes those with different views as unreasonable, ignorant, and even evil. Since we so infrequently interact with those politically different from us, we can find ourselves believing those characterizations. Although it may be hard to accept, most people, regardless of political affiliation, are genuinely trying to work towards the greater good. The difference between conservative and liberal thought, however, is in the means – how we achieve the greatest good. Conservatives, myself included, should therefore spend less time worrying that the left is deliberately attempting to destroy our country. Instead, we should intentionally befriend those politically different while, at the same time, working diligently to demonstrate that conservative policies most effectively create the most good for the most people. The more we are willing to acknowledge that those on the other side are people made in the image of God – not scheming adversaries to be defeated – the more likely we will arrive at solutions that work. While I believe that these solutions will be overwhelmingly conservative, we should not be afraid of honest discussion and criticism if we really are correct. One benefit of purposefully countering increased polarization is that we will, hopefully, stop being wary of good policy simply because it has some support from the other side. Some pursuits, like reforming civil asset forfeiture, supporting our veterans, and protecting our national security, are not right vs. left issues, but right vs. wrong issues. We should be thankful, not worried, when both sides agree. Undoubtedly, stemming the tide of polarization will be good for both Alabama and the country. It will require work, but it will be effort well spent. ••• Parker Snider is the Alabama Policy Institute‘s policy relations manager.