Will Sellers: In defense of the Electoral College

This article originally appeared in City Journal. I came of age politically with the 1968 presidential election. Alabama governor George Wallace was running as an independent against Richard Nixon and Hubert Humphrey. My parents were Nixon supporters, and I, their five-year-old son, hopped on the Nixon bandwagon with gusto. The dinnertime conversations in the month preceding the election were all about whether Wallace’s third-party candidacy could work. This all fascinated me, so I asked my mother to let me watch her vote on Election Day. She agreed, but to my dismay, when I joined her in the voting booth, I did not see Nixon, Humphrey, or Wallace listed on the ballot. This made no sense to me; I thought we were here to vote for Richard Nixon? My mother then explained that we didn’t vote for the presidential candidate directly. Instead, we voted for men and women called presidential electors. These people were well-regarded and appointed for the special privilege of casting the deciding votes in presidential elections. This system seemed out of place to me, because in every other election the candidates were listed by name on the ballot. Why not for president? Why should my mother vote for nine people, who would then vote later for president, instead of voting directly for the president? This was my first encounter with the Electoral College. It would not be my last. The first electoral college was a medieval construct dating back at least to the twelfth century, when specific princes were chosen to elect the Holy Roman Emperor. They were influential noblemen, who, because of the importance of their respective kingdoms, were given the hereditary title of “elector.” After the death of the emperor, they met, much like the College of Cardinals, to choose a successor. Whether this idea influenced the deliberations of the Constitutional Convention is speculation, but, like most of the other aspects of the Constitution, the mechanics of the new government were based on historical facets of self-government. The new American nation was built on traditions of representative government expressed in the English parliamentary system, the organization of Protestant church government, and the colonial experience with various local governments in the New World. Important questions necessarily arose during the Constitutional Convention concerning the process of electing the president. How exactly would a president be chosen, and to whom or what would he owe allegiance? Some advocated for election to take place in the House of Representatives, or in the Senate, or even in the several states. The obvious problem with these proposals is that they would create an axis between the president and the electing body. If the states elected the president, then the larger, wealthier, and more populous states would receive greater attention and more favorable treatment by the executive branch than would the smaller, less populous states. A similar imbalance of power would occur were the president chosen by the House or the Senate. Thus, the mechanics of electing the chief executive required balancing various interests to give the executive branch the requisite independence from other political bodies, while maintaining co-equality. According to the chosen scheme, each state would appoint “electors” based on the number of House and Senate members comprising the state’s congressional delegation. These electors were appointed for the sole purpose of electing the president, and a simple majority of their votes would decide the election. This created another means by which the spheres of Congress and the federal government were balanced and divided from that of the states. The Constitutional Convention viewed electors as not necessarily aligned with a faction, but as citizens of honesty, integrity, and political acumen. Originally, electors voted for two people; the person with the most electoral votes became president, and the runner-up became vice-president. Flaws in this system became evident with the presidential election of 1796, when John Adams was elected as president and his archrival, if not nemesis, Thomas Jefferson, was elected vice president. Four years later, Jefferson and Aaron Burr received the same number of electoral votes—neither had the required majority. This unworkable situation was remedied by the 12th Amendment to the Constitution, which prescribed that electors would separately vote for a president and vice president on the same ballot. Later, state legislatures, as they were constitutionally permitted and as the two-party system grew, allowed electors to run as proxies for the presidential and vice-presidential party nominee. For at least the first 100 years, the system worked well, and, other than the 12th Amendment, no major attempts were made to alter the process of electing the president and vice president. Several times, the election was submitted to the House of Representatives after the electors failed to achieve a majority vote for president. For example, in 1824, the election was submitted to the House, where power plays resulted in the election of John Quincy Adams, though Andrew Jackson won significantly more of the popular and the electoral vote. Rutherford B. Hayes, a Republican, lost the 1876 popular vote to Samuel Tilden, a Democrat, but became president because he had prevailed in the electoral vote, though voter fraud in some jurisdictions seemed certain. Many Democratic candidates running for federal office embraced the idea of abolishing the Electoral College, not least Sam Rayburn, who, in his first congressional election in 1912, advocated electing the president by popular vote. If there was any momentum for this aspect of the Progressive movement, it lost steam as other, more critical issues advanced. Today, the constitutional method for electing the president is under siege. The result of the 2016 election—with Donald Trump winning the presidency despite losing the popular vote—led pundits and politicians to call for the presidential election to be based on the popular, not electoral, vote. But lamenting results that saw two presidents in recent memory fail to win the popular vote obscures the effect that abolishing the Electoral College would have on a national campaign. A presidential campaign aimed at achieving a popular vote majority would completely ignore

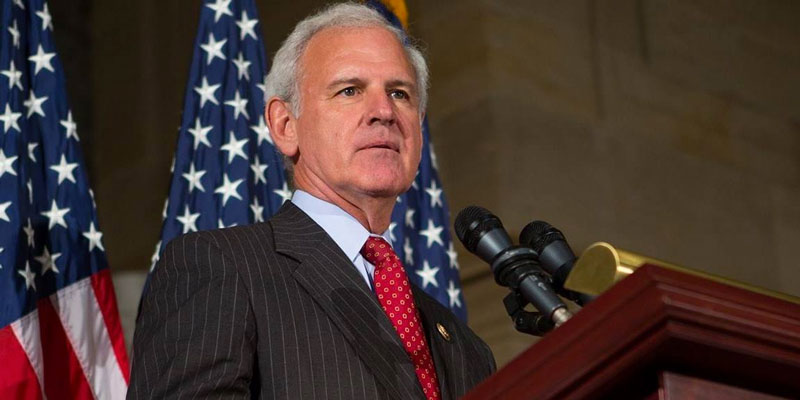

Bradley Byrne: After the election: One nation under God

I’ll never forget sitting in the US House Chamber in January of 2017, watching the counting of the Electoral College votes from the 2016 presidential election. Under the Twelfth Amendment to the Constitution, the sitting Vice President opens and counts the votes as submitted and certified by the electors chosen from each state, and the Vice President must do so “in the presence of the Senate and the House of Representatives.” Because Inauguration Day was still several days away, the sitting Vice President was Joe Biden, and as a member of the House, I was entitled to be there. Procedurally, any Representative or Senator can object to any state’s electoral college votes, but at least one member from the other house must agree with the objection before it can be considered. Alabama was the first state up, and Jim McGovern, a very liberal Democrat member from Massachusetts who served on the Rules Committee with me, stood up and objected because the Russians supposedly interfered with our vote for Donald Trump. He also made a blatantly false allegation that our state violated the Voting Rights Act and suppressed thousands of votes. No Senator agreed with him, and Vice President Biden ruled the objections out of order, which kept me from having to argue against McGovern’s silly and frankly slanderous objections. The count went on, and as every Trump state’s votes came up, a Democrat House member would stand up and object, but because no senator agreed with the objections, Biden would rule them out of order. Finally, after several of these, Biden leaned into the microphone and said firmly to his fellow Democrats, “it’s over.” Though they hated the result, he was saying, the Constitution calls for the person with the most electoral votes to be President. And that person was Donald Trump, not Hillary Clinton. This has been an extraordinary year, with the pandemic, a record economic downturn and recovery, riots and violence, and an unprecedented number of hurricanes. It will be an extraordinary election, too, as record numbers of people have already voted in many states, but their votes can’t be counted until election day, and many of those states’ election processes require days to count all those votes. There will also be challenges to the counting of some, perhaps many, ballots because they weren’t filled in or submitted properly. So, we aren’t likely to know the result on Election Day. We didn’t know the result of the 2000 election until December, weeks after the election, and that took an extraordinary decision by the Supreme Court to resolve it in favor of George W. Bush. The Twelfth Amendment was passed and ratified because the 1800 presidential election resulted in an electoral college tie between Thomas Jefferson and his supposed running mate Aaron Burr. That threw the election into the House of Representatives which took 36 ballots to finally make Jefferson the president, three months after the election. In both cases, the nation moved on and accomplished great things. Though this year’s election isn’t likely to be over as quickly as we are used to, all of us should be patient and trust in our Constitution and the institutions which have served us so well for over 230 years. There will be plenty of eyes on the process, and nothing inappropriate is going to go unnoticed. Our intelligence and law enforcement communities have been closely monitoring foreign actors and will continue to do so after the election. Be careful of the information you receive during and after the election because we know there’s a lot of truly fake “news” out there, designed to divide us as a nation. And when we have a result, if your candidate doesn’t win, let’s not have a replay of 2016 when Democrats refused to accept the result, who wouldn’t let it be “over” and shamefully called themselves the “resistance,” a slap in the face of the Constitution and our tradition of peaceful transfer of power. We’ve wasted too much time in Washington over the Mueller report and a failed impeachment effort, attempting to reverse the 2016 election. And we’ve had too much violence this year – we don’t need more due to the election. If your candidate loses, the appropriate response is to be the loyal opposition – loyal to our nation and its Constitution but opposed to the policies of the victorious party. Remember, in American politics, today’s loser is often tomorrow’s winner. Our greatest enemy isn’t a foreign nation but our internal division, driven by a hyper-partisan news media and entertainment industry ready to exploit every fault line in our country and craven before the far worse fault lines of countries where that industry makes a lot of money. Let’s ignore the media and entertainment industry and return to what we learned in school about the traditional values which make us great. As a unified nation there is nothing we can’t do, no problem or issue we can’t solve. We are one nation under God. Let’s keep it that way. Congressman Bradley Byrne currently represents Alabama’s 1st congressional district.

Darryl Paulson: The filibuster, the nuclear option and the future of American politics

What little Americans know about the filibuster is due to James Stewart‘s portrayal of Senator Jefferson Smith in the classic movie, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. In the movie, Senator Smith filibusters a fraudulent land deal until finally collapsing on the Senate floor. This past week, it was the filibuster that collapsed on the Senate floor as the “nuclear option” was invoked by Senate Republicans. History of the filibuster. The early Congress did not recognize the ability to filibuster. Senators could invoke a “previous question motion,” which meant that a simple majority could vote to end debate. Vice President Aaron Burr, as President of the Senate, streamlined the Senate rules in 1805 by persuading fellow Senators to abandon cutting off debate. That move allowed for the possibility of unlimited debate. The first filibuster did not occur until 1837, and the filibuster was seldom used in the 19th century. It was not until 1917 that the Senate adopted Rule 22 or the Cloture Rule, to create a mechanism to halt a filibuster. Rule 22 required a vote of two-thirds of the Senate (then 64 of the 96 senators) to halt a filibuster. Rule 22 came about in response to a request by President Woodrow Wilson to arm merchant marine vessels to protect them from U-boat attacks. A group of 11 progressive senators, led by Republican Robert La Follette of Wisconsin, blocked the bill. Wilson was outraged and condemned “A little group of willful men, representing no opinion but their own … have rendered the great government of the United States helpless and contemptible.” Filibuster rule changes. From 1917 to 1970, only 58 cloture petitions were filed (about one per year), and cloture was invoked only eight times. From 1971 to 2006, the number of cloture petitions jumped to 26 per year and cloture was imposed one-quarter of the time. From 2007 to 2014, cloture petitions were filed 80 times a year and half of the cloture votes were approved. As the use of the filibuster increased, the Senate looked at various ways to modify its use. In 1975, the Senate voted to make it easier to invoke cloture by requiring only a three-fifths vote instead of two-thirds. That would be a short-term solution with limited impact. In 2005, Republicans controlled the Senate and were concerned that Democrats would not approve nominees of George W. Bush. Republicans argued that the use of the filibuster on judicial nominations violated the constitutional authority of the president to name judges with the “advice and consent” of a simple majority of the Senate. Sen. Trent Lott of Mississippi used the word “nuclear” during the debate, and the concept of the “nuclear option” developed. Also in 2005, a “Gang of 14” senators, half Democrat and half Republican, reached a compromise to defuse the “nuclear option.” The Democrats promised not to filibuster Bush’s nominees except under “extraordinary circumstances,” and Republicans promised not to invoke the nuclear option unless they believed the Democrats used the filibuster in non-extraordinary circumstances. On Nov. 21, 2013, the Democrats triggered the nuclear option and eliminated the filibuster for all nominees except for the Supreme Court. They accused Republicans of filibustering an extraordinary number of President Obama‘s nominees. Republicans took back control of the Senate in the 2014 election and kept the Democratic rules in place. On April 6, 2017, Majority Leader Mitch McConnell extended the nuclear option to Supreme Court nominees after it was apparent that Democrats had the votes to filibuster the nomination of Neil Gorsuch to the court. The vote to change the rules to a simple majority passed 52-48 on a straight party-line vote, and the Senate then confirmed Gorsuch with 55 votes, as three Democrats joined the Republicans. Implications of the nuclear option. Now that the filibuster is dead in the nomination process, will it also fall by the wayside with respect to legislation? The answer is likely yes. The larger question is whether the filibuster is a good or bad part of the legislative process? Many argue that the Constitution is premised on majority rights and the filibuster allows a minority to dictate public policy. In other words, it is undemocratic. Supporters of the filibuster contend that it serves a useful purpose. Its use forces legislators to compromise in order to secure passage of major legislation. On controversial issues such as civil rights, a supermajority vote ensures that the legislation has widespread support and its passage was critical. When cloture was invoked on the 1964 Civil Rights Act after a 60-day filibuster, the first time cloture had been successful on a civil rights bill, it was a clear sign that national consensus had been achieved and a strong Civil Rights bill was needed. Critics of the filibuster argue there is no need to mourn its death. The filibuster has been a tool to frustrate the will of the majority and to impede passage of important legislation. Supporters counter that the death of the filibuster will lead to greater polarization, although that is hard to imagine. They argue that a simple majority vote will allow a president to appoint more extreme nominees and will allow the Senate to pass more extreme legislation. In addition, major legislation like Obamacare will be subject to “repeal and replacement” every time political control of the Senate shifts from one party to another. ___ Darryl Paulson is Emeritus Professor of Government at the University of South Florida in St. Petersburg.

Darryl Paulson: Voters don’t understand or like the Electoral College

Here are a few basic facts about the electoral-college system. First, very few voters understand how it works. Second, most voters hate the system. Third, the system is almost impossible to change. Those who drafted the Constitution had little trust in democracy. James Madison, in The Federalist Papers, wrote that unfettered majorities tend toward “tyranny.” John Adams, signer of the Declaration of Independence and second President, noted that “Democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes, exhausts, and murders itself. There never was a democracy that did not commit suicide.” Reflecting their distrust of democracy, the drafters of the Constitution wanted to create a process where the president would be indirectly selected. Direct election was rejected because they believed that most voters were incapable of making a wise choice. Voters would likely vote for a well-known person, especially one from a voter’s home state. A Committee of Eleven was appointed and they recommended a compromise where each state would appoint presidential electors equal to the number of representatives and senators. The electors would cast a vote for president and vice president. The candidate with the most votes would be president and the candidate with the second highest vote would be vice president. The compromise was accepted and Alexander Hamilton described the electoral-college plan “if the manner of it be not perfect, it is at least excellent.” The compromise worked until the 1800 presidential election when electors cast an equal number of votes for Thomas Jefferson, who the Anti-Federalists wanted to be president and Aaron Burr, who they wanted as vice president. After 36 ballots, the House selected Jefferson as president. The 12th Amendment, adopted in 1804, separated the electoral vote for president and vice president. There is little doubt that Americans hate the Electoral College system and prefer the direct election of the president. The system has allowed the election of four presidents who lost the popular vote, but won the electoral vote. In 1824, Andrew Jackson won the popular vote, but lost when the House selected John Quincy Adams. In 1876, Samuel Tilden won the popular vote by a quarter million votes, but lost the electoral vote to Republican Rutherford B. Hayes. In 1888, Grover Cleveland received more popular votes but lost to Republican Benjamin Harrison. Finally, in 2000, Democrat Al Gore won the popular vote, but lost the election when Florida’s electoral votes were awarded to George W. Bush. Another complaint about the electoral college is that the winner-take-all feature does not reflect the popular will. A candidate with a plurality of the popular vote would win all of a state’s electoral votes in a three or four person race. Critics contend that the system discourages candidates from campaigning in states that they are sure to win or lose. No sense wasting time and money campaigning in those states. Instead, all of the attention is focused on a half-dozen competitive states like Florida and Ohio. If no candidate gets a majority of the electoral votes (270), the election is thrown into the House of Representatives. Each state, regardless of population, gets one vote. The least populated state has one vote; the most populated state gets one vote. If a state delegation’s vote is equally split, they get no vote until the deadlock is broken. Although reforms of the system have been pushed, the likelihood of reform is small. Small states, which have disproportionate power under the plan, are not likely to give up that power to support direct election. Supporters of direct election argue that it is the most democratic, which is precisely why the drafters of the Constitution dismissed it. Supporters also argue that it would force candidates to conduct national campaigns since every vote would matter. Critics of direct election argue that it would create gridlock in close elections. Imagine having to review over 100 million votes in a close election to see if they should be counted or dismissed. Would voters have confidence if a candidate won by a few thousand votes? What does the electoral-college system tell us about 2016. Hillary Clinton is a flawed candidate seeking a third consecutive win for Democrats, something that is difficult to do. However, we know that Republicans are not happy with either Donald Trump or Ted Cruz. The possibility of a contested convention further muddies Republican chances. A look at the electoral-college maps shows that Democrats usually win fewer states than Republicans, but they win the states with large numbers of electoral votes. While the electoral-college map of America looks overwhelmingly red, it is likely the Republicans will end up feeling blue. Larry Sabato, of the University of Virginia, projects that in a Clinton-Trump election, Clinton is likely to win 347 electoral votes to Trump’s 191. If so, an easy Clinton victory means there will be no pressure to reform the electoral-college system. *** Darryl Paulson is Professor Emeritus of Government at USF St. Petersburg.