Orange Beach City Council bans short-term residential rentals

Orange Beach City Council members have voted to pass an ordinance that will ban short-term rentals in residential areas of the city. The council met Tuesday evening to discuss and vote on the ordinance. According to WPMI, city leaders made their decision in front of a packed house. In attendance were a number of realtors and homeowners who were interested in the ordinance. Under the new ordinance, residents are still able to rent out a room or home on sites such as Airbnb or VRBO (Vacation Rentals By Owner), but only if it’s for 14 or more days at a time. The new ordinance does not affect condo owners or any properties outside of a residential zone. Orange Beach now begins the process of creating a new “Vacation Rental” license which will allow homeowners to rent their own properties for 14 days or longer. Homeowners who already have the current short-term rental license will be grandfathered in but will be required to purchase a new license when their current one expires. Each license will cost around 500 dollars each year. Officials say they’re passing this ordinance as a safety measure and as a response to complaints from residents of the city; citing criminal activity, noise complaints, trash, and overflow parking. Some residents believe that the city is just looking for more sales tax revenue from condo rentals, and that this ordinance will prohibit some economic growth for the city. In 2017, Gulf Shores residents, Orange Beach’s next door neighbors, made $4.9 million and brought 27,700 guests into the coastal town using Airbnb, a short-term vacation rental company. Orange Beach is not the only Alabama city to make such a ban. In September, Mountain Brook banned all rentals less than 30 days.

Alabamians reap benefits of Airbnb

By sharing their homes with beach goers, tourists, and college football fans, Alabamians made over $16 million in 2017 using the popular home-sharing app Airbnb. Airbnb allows short-term accommodation seekers to book rentals online with individual hosts or property owners. According to their yearly totals, compiled from 114,000 guest arrivals in Alabama: The typical Alabama host shared their home 24 nights over the course of the year earning an extra $6,100 in income About 2,100 Alabama families hosted at least one Airbnb guest 57 percent of hosts in state are women Gulf Shores was the most visited Alabama destination, with hosts bringing in 27,700 guests and earning $4.9 million. Birmingham was the runner-up with 14,400 guest arrivals bringing in an extra $1.5 million. Tuscaloosa and Auburn were also popular destinations. Hosts in these cities earned over $1.1 million over the past two football seasons. Airbnb hosts in Alabama did more than make profits in 2017. In September while Hurricane Irma swept through Florida, many Florida residents traveled to Alabama for safe lodgings and to wait out the storm. Airbnb responded quickly and activated their emergency response program in several Alabama cities. The special listings for evacuees, in addition to having no list price, were free from Airnb’s fees and local/state taxes. One host in the Mobile area refunded her guests over $600 for their stay during the hurricane as a chance to “pay it forward.” “Home sharing through Airbnb continues to be a unique and flexible way for Alabama families to make more money, pay their bills, and support their communities,” said Public Policy Director for Airbnb in Alabama, Will Burns. “We look forward to 2018 being another successful year of giving residents in Birmingham, the Gulf Shores, Auburn, and all corners of the state an economic boost, travelers more affordable accommodations, and neighborhood businesses more foot traffic.”

Mountain Brook sets limit to short-term rentals like Airbnb, VRBO

In the absence of a statewide strategy to regulate short-term housing rentals, the Mountain Brook City Council approved an ordinance last week to set the minimum time period for short-term rentals. The ordinance, which amended Chapter 129 of the City Code, makes it unlawful to advertise or rent out a Mountain Brook residence for less than 30 consecutive days. Under the new ordinance, people would still be able to rent out a room or home on sites such as Airbnb or VRBO (Vacation Rentals By Owner), but only if it’s for 30 or more days at a time. According to the ordinance, it aims to protect the public health, safety and welfare while upholding the city’s standards in regard to residentially zoned property. It’s passage comes in the wake of neighborhood residents feeling unsafe as rentals frequently change guests, and residents are unfamiliar with who’s staying nearby.

Daniel Sutter: Technology, sharing, and disaster assistance

Hurricane Harvey struck Texas last weekend with winds of 130 mph and then stalled, dumping feet of rain and causing catastrophic flooding. Thousands of people evacuated coastal and low-lying areas in advance of Harvey. Home sharing company Airbnb’s Disaster Response program is helping Harvey evacuees and victims and illustrating how technology is helping us assist our fellow citizens. Airbnb provides a platform connecting people with homes, apartments or even spare rooms with visitors looking for rental accommodations. The company does not own or manage the properties it lists, but rather serves as an intermediary between visitors and hosts. Airbnb provides background on hosts and guests, helping assure each party that the other is legitimate. The disaster program emerged spontaneously after hosts in New York allowed people displaced by Hurricane Sandy to stay for free. Airbnb formalized this for other disasters. Participating hosts offer their properties for free, and Airbnb waives its commission. Both hosts and guests still benefit from Airbnb’s assurance of trust. The Disaster Response has been activated for almost 50 different events worldwide, producing over 3,000 free rentals. These totals almost certainly understate the assistance provided by hosts, as they exclude smaller events and include only free (as opposed to discounted) rentals. Airbnb activated the Disaster Response for Harvey before landfall to assist with evacuation. Evacuating can be expensive, with lodging typically the biggest expense for people unable to stay with family or friends. The expense often deters evacuation, particularly by lower income families without significant savings. Furthermore, hourly workers lose hours and income if they evacuate, upping the cost. Imperfect hurricane forecasts can unfortunately provide an excuse to not evacuate. For every devastating storm like Harvey or Katrina, there are storms like Matthew in 2016, which threatened Florida as a major hurricane yet delivered only a glancing blow before weakening and hitting South Carolina. If evacuating would break your budget, it is tempting to hope that the next storm will also be like Matthew. By helping families afford to evacuate, Airbnb’s Disaster Response will save lives. Keep this case in mind the next time someone claims that businesses care only about profit. Airbnb hosts display Americans’ desire to help people after disasters. For example, in our research, my Johnson Center colleague Dan Smith and I found that 98 percent of the 7,000 households displaced by the 2011 Joplin tornado relocated within 25 miles. FEMA provided about 600 temporary housing units, so most of the housing need was met without government. Some victims rented vacant housing, some stayed with friends and family, and still others stayed with neighbors or families from their church. The citizens of Joplin also housed many of the thousands of volunteers and youth groups who came to help after the tornado. Although Airbnb is not doing anything completely new, extending the scope of assistance after disasters is valuable. Many Americans want to help disaster victims however they can. Some people help by retweeting requests for help made via Twitter, an activity which has been dubbed “Voluntweeting.” People willing and able to offer material assistance, however, may lack connections to victims through friends or community groups. Airbnb helps connect people wanting to help with disaster victims. As an economist who studies weather disasters, I see an important challenge for Airbnb’s Disaster Response program, one which also looms for other uses of social media to direct aid to disaster victims. Are the persons staying with the hosts truly disaster victims, or just scamming a free stay? Airbnb’s guest profiles help hosts evaluate the validity of a guest’s disaster victim claims. Perhaps this will work well. But Airbnb’s program will probably not prove sustainable if hosts get scammed too often. Technology is enabling the emergence of a sharing economy. Airbnb’s Disaster Response uses technology to expand America’s long-standing tradition of neighbors helping neighbors in time of need. Here’s hoping that it works long term, and that we can find other ways to use technology to help us help our fellow citizens. ••• Daniel Sutter is the Charles G. Koch Professor of Economics with the Manuel H. Johnson Center for Political Economy at Troy University and host of Econversations on TrojanVision. The opinions expressed in this column are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of Troy University.

Daniel Sutter: The new power of sharing

Economic growth often involves new factories manufacturing more goods for us. But new forms of economic activity also contribute to prosperity. Ongoing innovations in the sharing economy can increase our standard of living without providing more goods. The best known firms in this new sector are ride- and home-sharing services Uber, Lyft, Airbnb and Home Away. These companies enable people to provide rides or lodging using their own cars or residences in exchange for payment. The use of existing cars and homes is the element of sharing. Many successful businesses have long facilitated sharing. The Uber and Airbnb examples show us that taxis, car rentals, and hotels all represent businesses built around sharing. Lawn services, bowling alleys and libraries also involve sharing. A lawn service uses its mowers to mow one lawn after another. By contrast, the mower you own and use sits in the garage most of the time. The new forms of sharing typically employ new technology, including the internet, smart phones, and social media. Technology is reducing transaction costs, which are the costs of carrying out buying, selling, and trading. Transaction costs often go unnoticed in the retail sector, but only because many innovations have routinized shopping at grocery or department stores, or now shopping online. Commerce-facilitating innovations include department stores, brand names, advertising, and credit cards. Many economists overlook transaction costs. But economists Douglas North and Oliver Williamson won Nobel Prizes for studying transaction costs. Some economic historians now view transaction cost reducing institutions as the fundamental source of modern prosperity. The market for used books illustrates how lower transaction costs make new trades profitable. The great challenge for exchange here is for sellers to find buyers interested in their books. Used bookstores offered a place for buyers to go to find a decent selection of titles. The excitement of discovering books you really wanted, however, really highlighted the limits of the process. Today anyone can buy or sell almost any book on Amazon Marketplace or eBay. Many new forms of sharing take the rental model. Social media allows the borrowing of tools, cookware, and trucks among a wider circle of friends. Extending borrowing circles is crucial in allowing people to find needed items. Sharing economy businesses are facilitating trading. And different modes of sharing exist. Uber offers rides by others, while Zipcar and Car2go rent cars owned by these companies for people to drive. Zipcar used technology to automate the rental process, allowing cars to be parked near where customers live. Most sharing economy businesses are really marketing innovations that reduce transaction costs. Airbnb’s background checks and rating systems, for example, increase the number of people willing to rent their homes, or pay to stay in a stranger’s home. Wise sharing will allow Americans to own less stuff, and the self-storage industry illustrates how valuable this might be. Today over 55,000 facilities nationwide have 2.5 billion square feet of space and earn annual revenues of $27 billion. About 10% of households rent a unit, and 65% and 47% of customers already have a garage or an attic – and still pay for more room. Sharing will let people tie up less of their wealth owning things that they rarely use. A University of California study found that each Car2go vehicle reduced the number of cars operated by residents of a city by 7 to 11. Essentially this means that one shared car can replace up to ten. Sharing allows people to avoid car payments, insurance, and parking, instead renting only when needed. A University of Massachusetts study estimates that many households could benefit $275 per year, which could rise to $1,000 with really extensive sharing. These savings will increase our prosperity, primarily by allowing peoples’ incomes to go further. We will instead have new and less expensive ways to access things we want to use. Innovative uses of technology constantly improve our lives, often by reducing transactions costs. The sharing economy is doing this today, providing an example where less is more. ••• Daniel Sutter is the Charles G. Koch Professor of Economics with the Manuel H. Johnson Center for Political Economy at Troy University and host of Econversations on TrojanVision. The opinions expressed in this column are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of Troy University.

Airbnb to collect, pay taxes on behalf of Alabama hosts

In a news release this week, the Alabama Department of Revenue (ADOR) announced that Airbnb will begin collecting remitting taxes for the department on its host sites in Alabama. Airbnb is a San Fransisco-based company that provides an online place to “list, find and rent short-term lodging,” most often in the houses of willing homeowners. The service offers a more personal lodging space for travelers interested in lower fares and a unique experience. In the past, taxes have been paid to the states by those people opening their homes for short-term lodging, a process that made it difficult for the state to collect and oversee such payments. The new agreement will have the company personally collecting the state’s Transient Occupancy Tax. This agreement adds Alabama to the list of a handful of other states already operating in this fashion. “This agreement will increase compliance in this area, and I commend Airbnb’s willingness to take the steps necessary to ensure that the appropriate taxes are being remitted,” ADOR Commissioner Julie Magee said in the news release. “It’s a win for both the state and for Airbnb customers.” The release goes on to say that the agreement with Airbnb will be a “huge benefit” for the state and generate “additional, much needed revenues.” Currently, there are more than 300 Alabama homes eligible for lodging on Airbnb’s website, some as low as $37 a night, with the majority in the Birmingham area.

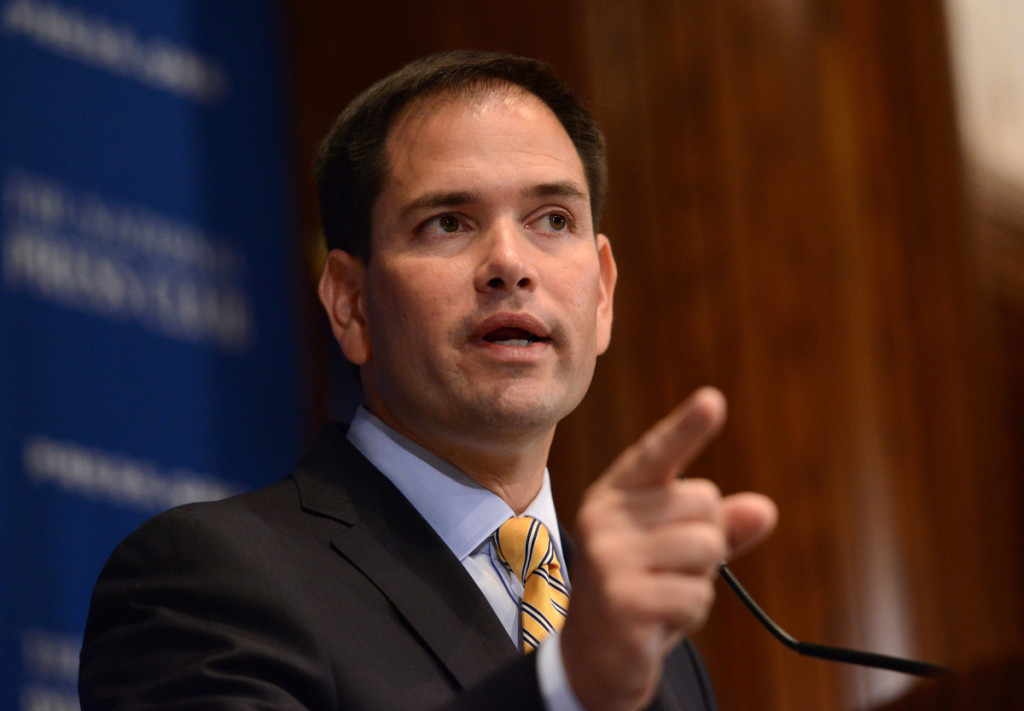

GOP 2016 candidate Marco Rubio criticizes government regulation of Internet-based on-demand economy

Republican presidential candidate Marco Rubio is warning of too much government meddling with Internet-based “on-demand companies.” Speaking Tuesday in New York, the Florida senator praised Uber and Airbnb. He says such “disruptive” companies and the people who work for them are unfairly burdened by government regulation. He decried the federal government as “out of touch” with Americans who want a high-tech, service economy. Rubio delivered his speech to a group of tech enthusiasts in New York City and he criticized local efforts to cap ride-sharing giant Uber and Airbnb, which helps people rent out their dwellings. Rubio praised Germany as creating a new tax classification for independent contractors who work for a single company. Republished with permission of the Associated Press.