Last troops exit Afghanistan, ending America’s longest war

The United States completed its withdrawal from Afghanistan late Monday, ending America’s longest war and closing a chapter in military history likely to be remembered for colossal failures, unfulfilled promises, and a frantic final exit that cost the lives of more than 180 Afghans and 13 U.S. service members, some barely older than the war. Hours ahead of President Joe Biden’s Tuesday deadline for shutting down a final airlift, and thus ending the U.S. war, Air Force transport planes carried a remaining contingent of troops from Kabul airport. Thousands of troops had spent a harrowing two weeks protecting a hurried and risky airlift of tens of thousands of Afghans, Americans, and others seeking to escape a country once again ruled by Taliban militants. In announcing the completion of the evacuation and war effort. Gen. Frank McKenzie, head of U.S. Central Command, said the last planes took off from Kabul airport at 3:29 p.m. Washington time, or one minute before midnight in Kabul. He said a number of American citizens, likely numbering in “the very low hundreds,” were left behind and that he believes they will still be able to leave the country. Biden said military commanders unanimously favored ending the airlift, not extending it. He said he asked Secretary of State Antony Blinken to coordinate with international partners in holding the Taliban to their promise of safe passage for Americans and others who want to leave in the days ahead. The airport had become a U.S.-controlled island, a last stand in a 20-year war that claimed more than 2,400 American lives. The closing hours of the evacuation were marked by extraordinary drama. American troops faced the daunting task of getting final evacuees onto planes while also getting themselves and some of their equipment out, even as they monitored repeated threats — and at least two actual attacks — by the Islamic State group’s Afghanistan affiliate. A suicide bombing on Aug. 26 killed 13 American service members and some 169 Afghans. The final pullout fulfilled Biden’s pledge to end what he called a “forever war” that began in response to the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, that killed nearly 3,000 people in New York, Washington, and rural Pennsylvania. His decision, announced in April, reflected a national weariness of the Afghanistan conflict. Now he faces condemnation at home and abroad, not so much for ending the war as for his handling of a final evacuation that unfolded in chaos and raised doubts about U.S. credibility. The U.S. war effort at times seemed to grind on with no endgame in mind, little hope for victory, and minimal care by Congress for the way tens of billions of dollars were spent for two decades. The human cost piled up — tens of thousands of Americans injured in addition to the dead, and untold numbers suffering psychological wounds they live with or have not yet recognized they will live with. More than 1,100 troops from coalition countries and more than 100,000 Afghan forces and civilians died, according to Brown University’s Costs of War project. In Biden’s view, the war could have ended 10 years ago with the U.S. killing of Osama bin Laden, whose al-Qaida extremist network planned and executed the 9/11 plot from an Afghanistan sanctuary. Al-Qaida has been vastly diminished, preventing it thus far from again attacking the United States. Congressional committees, whose interest in the war waned over the years, are expected to hold public hearings on what went wrong in the final months of the U.S. withdrawal. Why, for example, did the administration not begin earlier the evacuation of American citizens as well as Afghans who had helped the U.S. war effort and felt vulnerable to retribution by the Taliban? It was not supposed to end this way. The administration’s plan, after declaring its intention to withdraw all combat troops, was to keep the U.S. Embassy in Kabul open, protected by a force of about 650 U.S. troops, including a contingent that would secure the airport along with partner countries. Washington planned to give the now-defunct Afghan government billions more to prop up its army. Biden now faces doubts about his plan to prevent al-Qaida from regenerating in Afghanistan and of suppressing threats posed by other extremist groups such as the Islamic State group’s Afghanistan affiliate. The Taliban are enemies of the Islamic State group but retain links to a diminished al-Qaida. The final U.S. exit included the withdrawal of its diplomats, although the State Department has left open the possibility of resuming some level of diplomacy with the Taliban depending on how they conduct themselves in establishing a government and adhering to international pleas for the protection of human rights. The speed with which the Taliban captured Kabul on Aug. 15 caught the Biden administration by surprise. It forced the U.S. to empty its embassy and frantically accelerate an evacuation effort that featured an extraordinary airlift executed mainly by the U.S. Air Force, with American ground forces protecting the airfield. The airlift began in such chaos that a number of Afghans died on the airfield, including at least one who attempted to cling to the airframe of a C-17 transport plane as it sped down the runway. By the evacuation’s conclusion, well over 100,000 people, mostly Afghans, had been flown to safety. The dangers of carrying out such a mission while surrounded by the newly victorious Taliban and faced with attacks by the Islamic State came into tragic focus on Aug. 26 when an IS suicide bomber at an airport gate killed at least 169 Afghans and 13 Americans. Speaking shortly after that attack, Biden stuck to his view that ending the war was the right move. He said it was past time for the United States to focus on threats emanating from elsewhere in the world. “Ladies and gentlemen,” he said, “it was time to end a 20-year war.” The war’s start was an echo of a promise President George W. Bush made while standing atop of the rubble in

Donald Trump will own the war in Afghanistan that bedeviled predecessors

President Donald Trump is vowing to win what has seemed to be an unwinnable war. How he plans to do so is still murky despite the months of internal deliberations that ultimately persuaded Trump to stick with a conflict he has long opposed. In a 26-minute address to the nation Monday, Trump alluded to more American troops deploying to Afghanistan, but refused to say how many. He said victory would be well-defined, but outlined only vague benchmarks for success, like dismantling al-Qaida and preventing the Taliban from taking over Afghanistan. He said the U.S. would not offer Afghanistan a “blank check,” but provided no specific timetable for the end of an American commitment that has already lasted 16 years. Instead, Trump projected an “I got this” bravado that has become a hallmark of his presidency. “In the end, we will win,” he declared of America’s longest war. Victory in Afghanistan has eluded Trump’s predecessors: President George W. Bush, who launched the war after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, and President Barack Obama, who surged U.S. troop levels to 100,000, but ultimately failed in fulfilling his promise to bring the conflict to a close before leaving office. As Trump now takes his turn at the helm, he faces many of the same challenges that have bedeviled those previous presidents and left some U.S. officials deeply uncertain about whether victory is indeed possible. Afghanistan remains one of the world’s poorest countries and corruption is embedded in its politics. The Taliban is resurgent. And Afghan forces remain too weak to secure the country without American help. “When we had 100,000 U.S. troops in Afghanistan, we couldn’t secure the whole country,” said Ben Rhodes, who served as Obama’s deputy national security adviser. Trump offered up many of the same solutions tried by his predecessors. He vowed to get tough on neighboring Pakistan, to push for reforms in Afghanistan and to moderate ambitions. The U.S. will not be caught in the quagmire of democracy-building abroad, he said, promising a “principled realism” focused only on U.S. interests would guide his decisions. Obama promised much of the same. By simply sticking with the Afghan conflict, Trump’s plan amounts to a victory for the military men increasingly filling Trump’s inner circle and a stinging defeat for the nationalist supporters who saw in Trump a like-minded skeptic of U.S. intervention in long and costly overseas conflicts. Chief among them is ousted adviser Steve Bannon, whose website Breitbart News blared criticism Monday of the establishment’s approach to running he war. After Trump’s speech, one headline on the website read: “‘UNLIMITED WAR.” Another said: “What Does Victory in Afghanistan Look Like? Washington Doesn’t Know.” Now Trump leads Washington and that question falls for him to answer. As a candidate, he energized millions of war-weary voters with an “America First” mantra and now faces the challenges of explaining how that message translates to U.S. involvement in a war across the globe, likely for years to come. In a rare moment of public self-reflection, Trump acknowledged that his position on Afghanistan had changed since taking office and sought to sway his supporters who would normally oppose a continuation of the war. “My original instinct was to pull out,” Trump said. “But all my life I’ve heard that decisions are much different when you sit behind the desk in the Oval Office, in other words, when you’re president of the United States.” Trump pointed to “three fundamental conclusions” about U.S. interests in Afghanistan – all of which appeal to patriotism and nationalistic pride. The president said the nation needs to seek “an honorable and enduring outcome worthy of the tremendous sacrifices” made by U.S. soldiers – a line that harkened back to promises made by Richard Nixon during the 1968 campaign to bring “an honorable end” to the war in Vietnam. Trump also warned that a rapid exit would create a vacuum that terrorists like the Islamic State group and al-Qaida would fill, leading to conditions similar to before the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. And he noted that the security threats in Afghanistan are “immense,” and made the case that it is key to protecting the U.S. The U.S. currently has about 8,400 troops in Afghanistan. Pentagon officials proposed plans to send in nearly 4,000 more to boost training and advising of the Afghan forces and bolster counterterrorism operations against the Taliban and an Islamic State group affiliate trying to gain a foothold in the country. To those U.S. service members, Trump promised nothing short of success. “The men and women who serve our nation in combat deserve a plan for victory,” he said. “They deserve the tools they need and the trust they have earned to fight and to win.” Republished with permission of The Associated Press.

First-known combat death since Donald Trump in office

It’s been described as the greatest burden any commander in chief must bear. Just days into his young presidency, a U.S. service member has died in military action authorized by Donald Trump. It’s the first known combat death of a member of the U.S. military since Trump took the oath of office on Jan. 20 and underscores the gravity of the decisions he now makes. Three service members were also wounded Sunday during the firefight with militants from al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula’s branch in Yemen. The raid left nearly 30 others dead, including an estimated 14 militants. A fourth U.S. service member was injured when a military aircraft assisting in the mission had a “hard landing” nearby, according to U.S. Central Command. “Americans are saddened this morning with news that a life of a heroic service member has been taken in our fight against the evil of radical Islamic terrorism,” Trump said in a statement. “My deepest thoughts and humblest prayers are with the family of this fallen service member,” he said. The names of the casualties were not released. Planning for the clandestine counterterrorism raid begun before President Barack Obama left office on Jan. 20, but Trump authorized the raid, according to a U.S. defense official, who was not authorized to discuss details beyond those announced by the Pentagon and so spoke on condition of anonymity. The U.S. has been striking al-Qaida in Yemen from the air for more than 15 years, mostly using drones. Sunday’s surprise pre-dawn raid could signal a new escalation against extremist groups in the Arab world’s poorest but strategically located country. The action provides an early window into how the new president will put his campaign rhetoric into action when it comes to foreign intervention. Trump had promised an “America first” approach and an end to the “era of nation building” if he won the White House. Many interpreted his language as isolationist and expected Trump to be more cautious about where the U.S. intervened. At the same time, Trump had broadcast a stronger posture on the world stage. He pledged to beef up the military and said he aimed to achieve “peace through strength.” Sunday’s raid was not the first time that the United States had conducted a counterterrorism raid on the ground in Yemen, but it was not the usual approach of striking from the air, the defense official said. The raid was planned as a clandestine operation and not intended to be made public, but the loss of a service member changed that, the official said, adding that no detainees were taken in the operation. An al-Qaida official and an online news service linked to the terror group said the raid left about 30 people dead, including women and children. Among the children killed was Anwaar, the 8-year-old daughter of Anwar al-Awlaki, a radical Yemeni-American cleric killed in a U.S. airstrike in Yemen in 2011, according to the girl’s grandfather. Nasser al-Awlaki told The Associated Press that Anwaar was visiting her mother when the raid took place. She was shot in the neck and bled for two hours before she died, he said. In addition to killing the militants, White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer said U.S. forces “captured a whole host of information about future plots that’s going to benefit this country and keep us safe.” The president “extends his condolences,” he said on ABC’s “‘This Week.” ”But more importantly, he understands the fight that our servicemen and women conduct on a daily basis to keep this country safe.” Just over a week ago, suspected U.S. drone strikes killed three other alleged al-Qaida operatives in Bayda in what was the first-such killings reported in the country since Trump assumed the U.S. presidency. Al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula, long seen by Washington as among the most dangerous branches of the global terror network, has exploited the chaos of Yemen’s civil war, seizing territory in the south and east. The war began in 2014, when Shiite Houthi rebels and their allies swept down from the north and captured the capital, Sanaa. A Saudi-led military coalition has been helping government forces battle the rebels for nearly two years. Republished with permission of The Associated Press.

Donald Trump re-calibration: First act as President – ask Congress to declare war on ISIS

In case you missed it, the U.S. has been fighting an unconstitutional, undeclared war against Islamic terrorist enemies around the globe since 9/11. Its cost has been bleeding the American treasury and has depreciated the influence of America as the believable leader of the free world. When he takes office, Donald Trump’s first act as president should be to legitimize the prosecution of this war on Islamic terrorism by heading down Pennsylvania Avenue and asking Congress to legally declare war against ISIS. Trump’s mandate from the American electorate was premised in part on using unrestrained American military power to defeat ISIS and making “American Great Again” by building back and expanding US military capabilities and reach around the world. At the same time, Trump also has promised to bring a more restrained use of American interventionism. “We wanna strengthen all friendships and seek out new friendships,” Trump said at a postelection rally in Fayetteville, North Carolina. “Rather than a rigid dogma, we’re guided by the lessons of history, and a desire to promote stability all over and strength in our land. This destructive cycle of intervention and chaos must finally, folks, come to an end.” By asking for a declaration of war against ISIS (and al-Qaida too), President Trump would deliver on his promise not only to allow the United States to use the power and military might necessary to defeat these Islamic terror groups, but to actually illustrate that he is willing to restrain his presidential power to act alone in prosecuting and defining this war. Trump would also set a mission to actually end what has been an unwinnable war. This “War on Terror” as it stands today is an endless, illegal war, one whose mission, goals and objectives have never been truly defined with a declaration of war mandated both by the U.S. Constitution and the War Powers Act. It has been an undemonstrative series of military actions in a number of different nations of no true definition or ideology to measure victory or defeat. Both our soldiers and their generals have been severely restrained by the Obama administration’s adoption of a military strategy based on weak internationalist doctrine and coalitions, political correctness defined by leftist elites and journalists, and an irrational obsession with restricting civilian casualties that rule out the extreme force necessary to carry out the destruction of enemy – and its supporters too. It’s been a half-assed, stupid way of fighting a war. At the same time, Americans have become too accustomed, even complacent, to this eternal state of war. After 9/11, we were all riled up in a very patriotic way and told to be ready and observant. But after years of fighting that has accomplished little in terms of beating the enemy that is not allowed to be defined in real terms, our government now discounts its true threat to the American people and to diminish the significance and true costs of this state of war. Sadly, while we send drones and the USAF to bomb targets in the Middle East, we have deferred to the Russians, the Saudis, and the Iranians to directly deal with ISIS, to sort out the messes in Syria and Yemen. Even worse, at home, terrorist attacks such as the shootings at Fort Hood in 2009, the Boston Marathon bombing in 2013 and the San Bernardino attack in 2015 and the recent bombing in Manhattan in September are incorrectly termed as criminal matters. Couched cynically as acts by psychologically demented individuals acting alone, these acts of war by international terrorists quickly disappear from the news cycle and the consciousness of a nation. By definitively defining the enemy, an unrestrained scope of waging war, and the cost in blood and coin Americans need to suffer to eliminate a true threat to world stability and American democracy, a declaration of war would be both a defining moment for a new Trump Administration and a needed re-calibration of how our nation is governed and addresses this threat. It would be a truly significant first step in making “America Great Again.” ___ Steven Kurlander blogs at Kurly’s Kommentary and writes for FloridaPolitics.com. He is an attorney and communications specialist living in Monticello, New York. He can be reached at kurlyskommentary@gmail.com.

Ben Carson: Refugee program must screen for ‘mad dogs’

Republican presidential candidate Ben Carson said Thursday that blocking potential terrorists posing as Syrian refugees from entering the U.S. is akin to handling a rabid dog. At campaign stops in Alabama, Carson said halting Syrian resettlement in the U.S. doesn’t mean America lacks compassion. “If there’s a rabid dog running around in your neighborhood, you’re probably not going to assume something good about that dog,” Carson told reporters at one stop. “It doesn’t mean you hate all dogs, but you’re putting your intellect into motion.” Carson said that to “protect my children,” he would “call the humane society and hopefully they can come take this dog away and create a safe environment once again.” He continued: “By the same token, we have to have in place screening mechanisms that allow us to determine who the mad dogs are, quite frankly. Who are the people who want to come in here and hurt us and want to destroy us?” He later repeated the comparison at a rally at the University of South Alabama, while telling hundreds of supporters that reporters had misrepresented his earlier remarks. “This is the kind of thing that they do,” he said, drawing laughs and applause. Carson is among the GOP hopefuls who have called for closing the nation’s borders to Syrian refugees in the wake of the shooting and bombing attacks in Paris that killed 129 people and wounded hundreds more. The Islamic State has claimed responsibility for the carnage, stoking fears of future attacks across Europe and in the U.S. The retired neurosurgeon, who is near the top of many national and early state preference polls, said he’s been in touch with House GOP leaders about their efforts to establish new hurdles for Syrian and Iraqi refugees trying to enter the U.S. Dozens of Democrats joined majority Republicans in the House to pass the measure on Thursday. It would require the FBI to conduct background checks on people coming to the U.S. from those countries. The heads of the FBI and Homeland Security Department and the director of national intelligence would have to certify to Congress that each refugee “is not a threat to the security of the United States.” Asked whether he would sign it, Carson said he hasn’t reviewed the details. “If, in fact, it does satisfy basic needs for safety, of course,” Carson said. The Council on American-Islamic relations condemned Carson’s dog comparisons at the same time it blasted another GOP hopeful, Donald Trump, for declining to rule out setting up a U.S. government database and special identification cards for Muslims in America. “Such extremist rhetoric is unbecoming of anyone who seeks our nation’s highest office and must be strongly repudiated by leaders from across the political spectrum,” said Robert McCaw’s, CAIR’s government affairs manager. In Mobile, Carson said, “Islam itself is not necessarily our adversary.” But he said Americans are justified in seeing threats from Muslim refugees and the U.S. shouldn’t “completely change who we are as Americans just so we can look like good people.” He continued: “We have an American culture, and we have things that we base our values and principles on. I, for one, am not willing to give all those things away just so I can be politically correct.” Separately, Carson said Thursday that Islamic State militants are more organized and sophisticated than the al-Qaida terrorists who carried out the 9/11 attacks. Those attacks, he said, “really didn’t require a great deal of sophistication because we weren’t really paying attention.” He added, “You didn’t have to be that great. You had to be able to fly a couple of planes. You’re going to have to be a lot more sophisticated than that now.” Carson’s spoke a few days after some people in and around his campaign offered public concerns about his command of foreign policy. The chief critic, former CIA agent Duane Clarridge, told The New York Times that Carson struggles with Middle Eastern affairs. He “not an adviser,” Carson said, adding that Armstrong Williams, his longtime business manager, also “has nothing to do with my campaign.” Williams spoke to the Times, the Associated Press and other media about Carson’s need to improve as a candidate. Carson described Williams as an independent operator who “speaks for himself.” But, Carson acknowledged, Williams as recently as this week helped the candidate edit a foreign policy op-ed the campaign sent to The Washington Post. Republished with permission of the Associated Press.

Martin Dyckman: The road to Middle East stability isn’t through war

Remember “freedom fries?” That was how some Americans expressed their spite toward France when that nation, with vastly more experience than ours in the Middle East, wisely declined the opportunity to participate in George W. Bush‘s ego-driven war on Iraq. There was a congresswoman from Florida who called for exhuming our military graves and bringing the remains home. She was ignorant of the fact that a grateful France had ceded those sites to the United States forever. The heartbreakingly beautiful cemetery atop the Normandy beachhead is as much American soil as Arlington itself. But in Paris on Friday, France paid a terrible price for the chaos we created when we invaded Iraq and destroyed its government with no thought of history or of the consequences beyond the premature boast, “Mission accomplished.” The evil we didn’t know proved to be worse than the evil we did. Saddam Hussein, for all his crimes, was a stabilizing influence on Iraq and an effective counterweight to Iran – which, unlike Iraq, had declared its enmity of the U.S. and remains an essential ally of the Syrian dictatorship that provides the so-called Islamic State with a plausible raison d’etre. When Bush’s civilian viceroy sacked the entire Iraqi army, he created legions of recruits for al-Qaida and its successor, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria – aka ISIS. Our failure in nation-building created a corrupt prime minister, Nouri Kamal al- Maliki, whose refusal to renew the status of forces agreement gave President Obama no choice, whatever other he might have chosen, but to bring all our troops home. No president of either party could have left them there exposed to Iraqi laws, arrests and prosecutions. To understand this history is to be warned against repeating it. But America doesn’t learn that lesson very well. Vietnam should have taught us the difficulty of imposing our values on a different culture and to be leery of war where our national interest is not at stake. But the only lesson the politicians took to heart from that unpopular lost war was to abandon the draft and fight the next one with a volunteer force, a force that has been cruelly abused with too many successive combat deployments. In the aftermath of the Paris massacres, we will be hearing again, from the usual suspects, that it’s time to unleash American military might to whatever extent it takes to exterminate ISIS. But even if we could do that – and we can’t – something else would take its place, just as the burgeoning ISIS supplanted a decapitated al-Qaida. The Democratic presidential candidates were right as they agreed, in their separate ways Friday night, that the fight against ISIS must be led by the Muslim states that are the radical movement’s primary intended victims. The United States can help, and should. We are helping already, as are the French, and there is surely more that we can do, short of sending sophisticated weapons to dubious allies who might surrender them to ISIS. But it cannot be seen as an American war, or as French or British. The more important point is that the ultimate solution can not be military. That can only prolong the strife and suffering. By coincidence, the Imam of Asheville’s Muslim community, Egyptian-born Mohamed Taha, was the scheduled speaker Sunday at a brunch sponsored by the Brotherhood of my Reform Jewish congregation. It was well-attended. He talked mainly about the beliefs of Islam and its many similarities to Judaism, and its devotion to peace. But the slaughter at Paris hovered over the morning. “These people,” he said, speaking of ISIS and its ilk, “they are extremists. The majority of Muslims don’t consider these people as Muslims. Mohamed warned against such people … they take some verse of the Koran and they twist its meaning. “They don’t,” he added, “consider us as Muslims.” To defeat the jihadists, he said, requires overcoming the conditions they exploit. “They live in poverty,” he said of the populations where the jihadists enlist most of their support. “They have nothing. We have to help them to establish good countries, good communities. They have nothing in this life, so the extremists promise them everything in the next life.” The solution is not military. The wiser of our American experts on the Middle East, notably including The New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman, have been saying that for years. After World War II, the United States deployed a non-military solution, the Marshall Plan, to help a ravaged Europe rise to its feet in democracy rather than communism. We surely could use a Marshall plan for the Middle East. But how to help the people there to their feet without having the assistance stolen by the corruption that is endemic among the rulers there? I asked that question. Taha acknowledged the difficulty. It begins, he said, with affording an American education, steeped in American traditions and values, to Middle Eastern students who want to study here. Inevitably, perhaps, some few of those students will have other values in mind, like those who prepared here for 9/11. And in the aftermath of Paris, there are politicians who would slam the door, to students as well as refugees, for fear of the few who would exploit our hospitality. But that would be a mistake. It would betray that our values are not, in truth, what we would wish them to be. It would postpone the redemption of the Middle East and perpetuate a war that cannot be won by arms alone. Martin Dyckman is a retired associate editor of the newspaper formerly known as the St. Petersburg Times. He lives in Asheville, North Carolina.

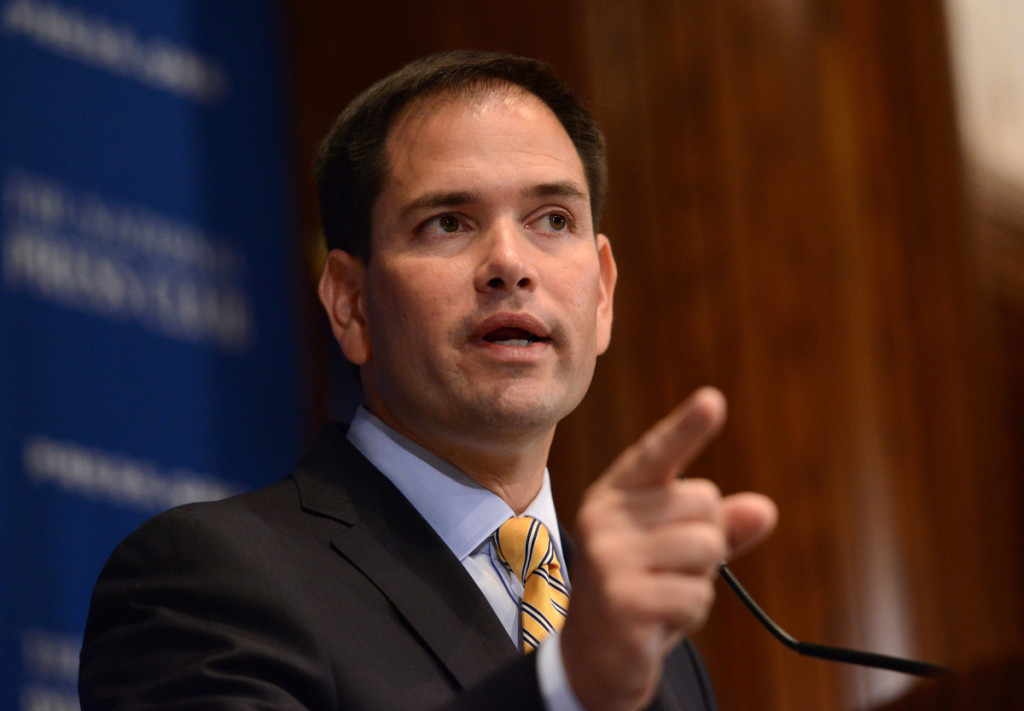

GOP candidates divided over renewing USA Patriot Act

Republican senators eyeing the presidency split over the renewal of the USA Patriot Act surveillance law, with civil libertarians at odds with traditional defense hawks who back tough spying powers in the fight against terrorism. The political divide will be on stark display this month as Congress debates reauthorization of the post-Sept. 11 law ahead of a June 1 deadline. The broader question of privacy rights has gained attention since a former National Security Agency systems administrator, Edward Snowden, disclosed in 2013 that the NSA had been collecting and storing data on nearly every American’s phone calls for years. On one side, Sens. Marco Rubio of Florida and Lindsey Graham of South Carolina want Congress to permanently reauthorize parts of the law, giving the NSA much of its surveillance authority. If there were another attack, “the first question out of everyone’s mouth is going to be, `why didn’t we know about it?’” Rubio said this week in a speech on the Senate floor. “And the answer better not be, `because this Congress failed to authorize a program that might have helped us know about it.’” The rise of Islamic State militants, the continued threat from al-Qaida and the ongoing civil war in Syria have pushed national security to the forefront in the 2016 race for the GOP nomination, with some candidates determined to show their toughness. On NSA surveillance, however, Americans are wary of government intrusion. Sens. Ted Cruz of Texas and Rand Paul of Kentucky say the law infringes on citizens’ privacy. “They want nothing more than to keep the national security spy state growing until it tracks, traces and catalogues virtually every detail about every aspect of our lives,” Paul said in a campaign email to his supporters. “Once government bureaucrats know every aspect of our lives – what we watch, what we buy, what we eat, where we worship – it won’t be long until they try to run them `for our own good.’” Under the law, the NSA collects information on the number called and the date and time of the call, then stores it in a database that it queries using phone numbers associated with terrorists overseas. Officials say they don’t use the information for any other purpose, and that the legal powers that enable the program are essential to the hunt for terrorists. Opponents say the seizure and search of telephone company records violates Americans’ expectations of privacy under the Fourth Amendment. Adding a wrinkle to the debate was Thursday’s federal appeals court ruling that the bulk collection of Americans’ phone records is illegal. The court all but pleaded for Congress to sharpen the boundaries between security and privacy rights. The House is slated to vote next week on a bill to reauthorize the law while also ending the government’s dragnet collection of records, and Cruz has endorsed the measure, saying it “strikes the right balance between privacy rights and national security interests.” But Senate leaders, including Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., and Sen. Richard Burr, R-N.C., the chairman of the Intelligence Committee, have spoken forcefully for a competing measure to reauthorize the law as-is. Across Congress, the political divisions cut along complex lines. Libertarian-leaning Republicans like Cruz and Paul are aligned with many liberal Democrats, insisting that a secret intelligence agency should not be storing the records of every American phone call. But other Democrats and Republicans say the program is needed now more than ever given the Islamic State group’s determination to inspire terrorist attacks on American soil. Graham, the only one of the four who has not formally announced his candidacy, is siding with Rubio in favor of the NSA’s spy powers but competing with him for support among defense hawks. “I’m open-minded to doing reforms,” Graham told reporters Thursday. “I just don’t want to diminish the capacity of the program to prevent another 9/11. I believe if the program were in operation before 9/11, we probably would have prevented 9/11.” Sen. John McCain, the GOP’s 2008 presidential nominee, previewed one likely argument. He cited the incident in Texas last Sunday in which two gunmen were shot dead while trying to attack a provocative event that featured cartoon images of the Prophet Muhammad. In the aftermath, authorities described an alarming trend involving potential homegrown extremists with access to social media and possible exposure to Islamic State group propaganda. “We must do everything in our power to stop these attacks before they happen,” McCain, the Senate Armed Services Committee chairman, said. FBI Director James Comey said Thursday that although the bureau had opened a new investigation into one of the gunmen, Elton Simpson, agents had no reason to believe he was going to attack the event. Republished with permission of the Associated Press.