Attorneys praise judge’s order to boost Alabama prison staff

Attorneys for inmates praised a sweeping ruling issued Monday by a federal judge that will require Alabama’s prison system to make changes in inmate mental health care. U.S. District Judge Myron Thompson issued a sometimes scathing 600-page opinion that often focused on the prison system’s lack of progress in meeting an earlier directive to boost staffing and also on the number of suicides that have occurred behind bars. The Monday order spelled out corrective measures and comes after Thompson in 2017 ruled that Alabama’s “horrendously inadequate” care of mentally ill inmates violated the U.S. Constitution’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment. The ruling came after a two-month trial in which attorneys for inmates argued the state continued to fail to provide adequate care. “Judge Thompson’s decision requires ADOC to finally remedy the unconstitutional mental health care identified more than four years ago. This will ensure that the individuals held by ADOC will receive the mental health care they need – and are entitled to – as protected by the Eighth Amendment,” Ashley Austin, an attorney at the Southern Poverty Law Center, said in a statement. Austin said if the prison system is unable to “operate adequately with the current staff and funds allotted to it by the state, population reduction must be the consideration – not denial of adequate services.” Thompson sharply criticized the state’s lack of progress in meeting a 2022 deadline. He said staffing has barely increased in three years, and the system has filled less than half of the positions necessary to meet the requirement of 3,826 full-time-equivalent officers. The judge had previously directed the state to meet staffing targets by Feb. 20, 2022, but wrote Monday that it’s become clear that it is “out of reach.” Thompson extended the deadline to July 1, 2025, for the state to fill all mandatory and essential posts, but he also ordered the creation of yearly benchmarks to measure progress. “As Judge Thompson reminds all Alabamians, once our state chooses to put a person in prison, the state must provide a safe environment and adequate mental health care. Here, the state has failed to do so. Too many individuals have died because of the state’s failures,” James Tucker, director of the Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program, said in a statement. The two organizations filed a lawsuit against the prison system in 2014 on behalf of incarcerated inmates. Thompson ordered the state to make numerous other changes to mental health care, including ensuring that inmates get some time out of their cells, that security checks are regularly conducted, that assessments are properly done, that inmates who require hospital-level care receive it within a reasonable period of time and that staff conduct regular drills on how to respond to suicide attempts. Thompson also ordered that before being discharged from suicide watch, an inmate must receive a confidential, out-of-cell evaluation by a mental health professional and then follow-up examinations for three days. In the four years since his initial ruling, Thompson said at least 27 more prisoners have died by suicide, and he described some of the incidents. Thompson said the state has a “mixed” track record in making other improvements in the care of mentally ill inmates. He noted the state had made improvements in the number of mental health workers. A spokesperson for the Alabama Department of Corrections said the department could not immediately respond. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Attorneys reviewing judge’s order on prison staffing, care

Attorneys for inmates say they are reviewing a federal judge’s ruling that extended a deadline for Alabama to increase prison staffing but also ordered other changes to the care of inmates with mental illnesses. U.S. District Judge Myron Thompson on Monday issued a massive 600-page opinion regarding corrective measures for mental health care in state prisons. Thompson in 2017 ruled that mental health care in state prisons was so “horrendously inadequate” that it violated the U.S. Constitution’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment. “We are reviewing this ruling now but are gratified by the time and care Judge Thompson has put into this issue,” Larry Hannan, a spokesperson for the Southern Poverty Law Center, wrote in an email. Thompson chided the state for the lack of progress in addressing a shortage of correctional officers, an issue that he said was at the root of many of the problems. The federal judge extended a deadline from 2022 until 2025 for the state to adequately staff prisons but said the state should meet yearly benchmarks. According to the opinion, attorneys representing inmates had asked Thompson to enforce his original 2022 deadline. Thompson wrote he was adopting a “hybrid of the timelines proposed” by the two sides. He granted the state an extension but said yearly staffing benchmarks will be developed for the prison system to meet by the end of 2022, 2023, and 2024. “However, when the amount of work (much of which should have been done years ago) ADOC must put into achieving adequate correctional staffing is considered, July 2025 is just around the corner. Time is of the essence. Every week and month is dear. The court, therefore, agrees with the plaintiffs that it is necessary to impose certain intermediate benchmarks against which ADOC’s progress may be assessed,” Thompson wrote.

Alabama prison staffing numbers fell over 12 months

The Alabama prison system, already understaffed and facing a federal court order to boost employment numbers, saw the number of correctional staff decline 4% during the pandemic. The Alabama Department of Corrections had 1,914 officers and supervisors in the quarter that ended June 30, 2021 — a 50% vacancy rate. But that fell to 1,837 at the end of June 30, 2021, boosting the vacancy rate to 52%. The numbers were listed in most recent staffing reports the system is required to file with the federal court. While staff shortages have long been a problem for corrections agencies, the pandemic brought new challenges for systems across the country. In Alabama, that comes as the state faces the dual pressure of a Department of Justice civil lawsuit and a separate court order out of a mental health care lawsuit to boost staffing. Kyle Mays, 36, this year left his job of 11 years at Limestone Correctional Facility because he said the stress of working inside the prison was beginning to take a toll. He took a pay cut to take a job in manufacturing. “It has gotten worse by far worse,” Mays said of conditions inside prisons. At the maximum-security prison where he worked, he said there would be five roving officers trying to supervise a general population of about 1,600 inmates. He said most incidents occur during mealtimes when officers are pulled to the dining area, “because there is no security in the dormitories.” “It’s very dangerous, but it’s a lot more dangerous for the inmates.” Mays said. Kristi Simpson spokesperson for the Alabama Department of Corrections said the department saw a small decline in staffing but said the problem is not unique to the prison system. She said the department could not comment on the staffing situation described at Limestone because of the ongoing litigation. “Public and private organizations across the nation are facing unprecedented workforce shortages and recruitment challenges due to the dynamics of the labor market… More broadly speaking, correctional and law enforcement organizations across the nation are struggling to fill vacant positions due to the challenging/stressful nature of the work and evolving cultural influences,” the department said in a statement. The prison system has used a statewide recruitment campaign, the creation of new security positions, pay raises, and other efforts to boost staffing. “We believe we have made as much progress as was possible with the resources available to us juxtaposed against a global pandemic and unprecedented labor market challenges.” U.S. District Judge Myron Thompson in 2017 ruled that mental health care in prisons was “horrendously inadequate” and said low staffing was a root cause. He ordered the prison system to add as many as 2,000 officers. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Prison commissioner stepping down from troubled department

Alabama Corrections Commissioner Jeff Dunn is stepping down after six years leading the troubled system that faces a Justice Department lawsuit over prison conditions, the governor’s office announced Tuesday. Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey said she is appointing John Hamm, the current deputy secretary of the Alabama Law Enforcement Agency, as the state’s next corrections commissioner. Hamm will take over on Jan. 1. “I have said before that Commissioner Dunn has a thankless job, but I am proud that he has led with the utmost integrity. He has helped lay the groundwork that I now look forward to building upon with John Hamm at the helm,” Ivey said in a statement. Dunn was appointed by then-Gov. Robert Bentley in 2015 to lead the troubled prison system. A retired Air Force colonel, Dunn had no experience in corrections, but Bentley said he would bring a fresh perspective to the department. He remained in the position under Ivey. During his tenure, Dunn sought additional funding to hire and retain corrections officers and helped lead the push under two administrations for prison construction. Lawmakers this year approved a plan to tap pandemic relief funds to help pay the costs of building two new super-size prisons and renovating other facilities. But his tenure also saw an ongoing prison violence crisis — at least partly fueled by the ongoing staffing shortage— and mounting troubles for the department. The Justice Department filed a civil lawsuit against Alabama last year, saying state lockups were among the deadliest in the nation and that inmates face unconstitutional levels of “prisoner-on-prisoner and guard-on-prisoner violence.” The Justice Department state officials have been deliberately indifferent to the problem. “In the two and a half years following the United States’ original notification to the State of Alabama of unconstitutional conditions of confinement, prisoners at Alabama’s Prisons for Men have continued daily to endure a high risk of death, physical violence, and sexual abuse at the hands of other prisoners,” the DOJ wrote in an updated complaint filed last month. It was signed by Attorney General Merrick Garland. U.S. District Judge Myron Thompson in 2017 ruled that Alabama’s psychiatric care of state inmates is so “horrendously inadequate” that it violates the U.S. Constitution’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment. State Rep. Chris England, who has long called for Dunn’s removal, said this was an opportunity to take the department in a new direction. He said leadership change is also needed at the parole board. Ivey’s office said Hamm has more than 35 years of experience in law enforcement and includes time working in corrections at both the state and local levels. “I will work diligently with the men and women of DOC to fulfill Governor Ivey’s charge of solving the issues of Alabama’s prison system,” Hamm said in a statement released by the governor’s office. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

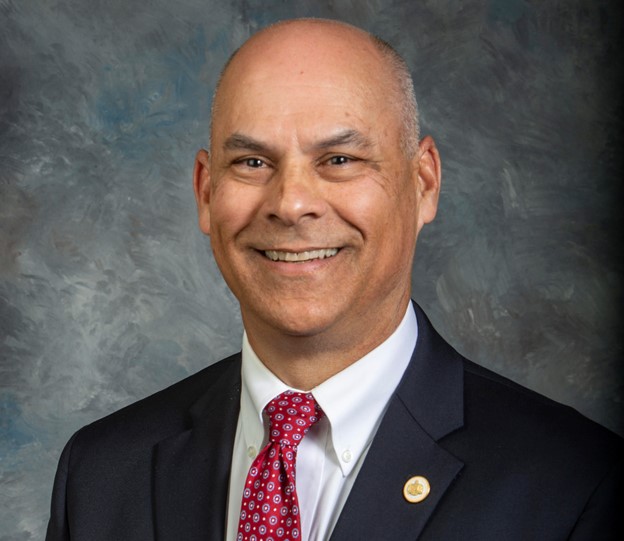

Kay Ivey taps veteran John Hamm to lead Department of Corrections

Kay Ivey announced Tuesday that she is appointing law enforcement veteran John Hamm to serve as the next commissioner for the Department of Corrections. Hamm is currently the deputy secretary of the Alabama Law Enforcement Agency (ALEA). After almost seven years in his position, Commissioner Jeff Dunn plans to step down at the end of December. Hamm’s appointment is effective January 1, 2022. Ivey praised Dunn for his efforts in improving Alabama prisons. In a press release, Ivey commented, “For decades, the challenges of our state’s prison system have gone unaddressed and have grown more difficult as a result, but after assuming office, I committed to the people of Alabama that we would solve this once and for all. Commissioner Dunn and I have worked together to make many foundational changes, including getting the Alabama Prison Plan moving across the finish line, and I know this critical step will make a difference for decades to come.” Ivey continued, “I have said before that Commissioner Dunn has a thankless job, but I am proud that he has led with the utmost integrity. He has helped lay the groundwork that I now look forward to building upon with John Hamm at the helm.” Hamm has 35 years of law enforcement experience. He was at the helm of the State Bureau of Investigation before serving as deputy secretary of ALEA. His extensive law enforcement background also includes work in corrections, both at the state and local levels. Hamm holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Justice and Public Safety from Auburn University at Montgomery. “Ensuring public safety is at the forefront of our mission when it comes to the Alabama Department of Corrections. From protecting our inmates to correctional staff to the public, that must be a top priority, and we will have a strong leader in John Hamm,” said Governor Ivey. “We have taken important steps, and now, we must build upon those, and John has committed to me that he is prepared to do just that. I am confident in the direction we will take this department in the coming years.” Hamm commented, “I am honored and humbled by Governor Ivey appointing me as commissioner of Corrections. I will work diligently with the men and women of DOC to fulfill Governor Ivey’s charge of solving the issues of Alabama’s prison system.” “Ensuring public safety is at the forefront of our mission when it comes to the Alabama Department of Corrections. From protecting our inmates to correctional staff to the public, that must be a top priority, and we will have a strong leader in John Hamm,” said Governor Ivey. “We have taken important steps, and now, we must build upon those, and John has committed to me that he is prepared to do just that. I am confident in the direction we will take this department in the coming years.”

Alabama prisons to resume visitation after 20 months

Alabama prison inmates will soon be allowed personal visitors for the first time in 20 months, but there will be a number of restrictions. The Alabama Department of Corrections said in a news release that visitation will resume December 4. Visitation had been suspended since March of 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic began. “We are pleased to share that the ADOC has reached a point where it is safe, at this time, to expand modified visitation and work release/work center activities statewide effective December 4, 2021. As COVID-19 still poses a significant risk in a correctional environment, several safety protocols and restrictions will be in place and must be adhered to as we expand these activities statewide,” the department said in a statement. Inmates can only have two visitors at a time, including children. Visitors will be seated six feet from the inmate with a plexiglass barrier between them. No hugging or touching will be allowed. Visits will be limited to one hour, and no eating or drinking will be allowed. Alabama was one of the last states to have to resume prison visitation, according to The Marshall Project. As of July 30, Alabama was one of 10 states that had not resumed personal visits, according to the organization. Alabama had also suspended legal visits until this summer. The prison system did make video visitation available and personal devices so inmates could send messages or place calls. “We would also note that we have made significant efforts to provide incarcerated people in Alabama with access to resources that enable them to communicate with their loved ones while in-person visitation is suspended,” a spokeswoman for the department wrote in an earlier email. Elizabeth Hancock, a college instructor with a doctorate in counselor education and supervision and who also serves as president of the inmate advocacy group Unheard Voices O.T.C.J., said it is psychologically damaging for people, on both sides of the bars, to go for so long without seeing loved ones. “Not having that human touch can be very, very hard. It’s one of the things people in nursing homes struggle with too,” Hancock said. She said the inmates and family members were excited for visitation to resume but the restrictions are disheartening and could end up discouraging visitation. Young children won’t be able to hug their parents and inmates won’t be able to see more than one minor-age child at a time, she said. “Once again, ADOC has disregarded all rehabilitation purposes of visits and its importance to the mental health of those incarcerated as well as the family,” the group said in a statement. Surrounding states resumed visitation earlier and some have fewer restrictions. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Former guard sentenced for trying to bring drugs into prison

A former Alabama Department of Corrections guard was sentenced to more than seven years behind bars for distributing methamphetamine in the state prison where he worked. Senior U.S. District Court Judge Karon O. Bowdre sentenced Gary Charles Dixon, Jr., 36, on Wednesday to 87 months in prison on one count of distribution of 50 grams or more of methamphetamine. Dixon pleaded guilty to the charges in July. “Smuggling contraband into our state prisons compromises the safety of everyone in the facility,” U.S. Attorney Prim F. Escalona said in a news release. The U.S. attorney’s office said Dixon in 2020 attempted to smuggle 497 grams of methamphetamine into William E. Donaldson Correctional Facility in Bessemer where he was employed as a corrections officer. The Department of Justice last year sued Alabama, saying the state prisons for men are “riddled with prisoner-on-prisoner and guard-on-prisoner violence.” The Justice Department in 2019 cited illicit drugs as one of the contributing factors to the overall unconstitutional conditions along with understaffing, culture, management deficiencies, corruption, and other problems. The state has acknowledged problems in state prisons but has disputed the Justice Department’s allegations. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

2 inmates killed within a week in state prisons

Two inmates were killed within a week in reported assaults in Alabama prisons, a system that is facing a U.S. Department of Justice lawsuit over excessive violence. Kristi Simpson, a spokeswoman for the Alabama Department of Corrections, confirmed the deaths and said they are under investigation. The Jefferson County Coroner’s Office said a 31-year-old inmate died Monday morning after a reported assault at Donaldson Correctional Facility. The Alabama Department of Corrections identified the man as Kenneth Gilchrist. Gilchrist “unfortunately passed away from injuries sustained during an apparent inmate-on-inmate assault with a weapon,” Simpson wrote in an email. The coroner’s office said the assault occurred in the prison’s common area. She said Travis Hutchins, a 34-year-old inmate at Bibb Correctional Facility, died Thursday of injuries from another inmate-on-inmate assault involving a weapon. Both deaths are under investigation by the Alabama Department of Corrections Law Enforcement Services Division, Simpson said. She said the exact causes of death are pending the results of full autopsies. Gilchrist was serving a 25-year sentence for a first-degree burglary conviction. Hutchins was serving a 20-year sentence for a murder conviction. When Hutchins was an inmate at Easterling Correctional Facility in 2016, he filed a lawsuit against the warden, assistant warden, and two correctional officers over injuries he suffered in another assault, al.com reported. The U.S. Department of Justice last year filed a lawsuit against Alabama accusing the state of failing to protect male inmates from inmate-on-inmate violence and excessive force at the hands of prison staff. The lawsuit alleged that conditions in the prison system — which the Justice Department called one of the most understaffed and violent in the country — were so poor that they violated the ban on cruel and unusual punishment and that state officials were “deliberately indifferent” to the problems. The Alabama Department of Corrections has acknowledged problems in state prisons but disputes the Justice Department’s accusations.

Alabama trying to use COVID relief funds for new prisons

Facing a Justice Department lawsuit over Alabama’s notoriously violent prisons, state lawmakers on Monday began a special session on a $1.3 billion construction plan that would use federal pandemic relief funds to pay part of the cost of building massive new lockups. Gov. Kay Ivey has touted the plan to build three new prisons and renovate others as a partial solution to the state’s longstanding troubles in its prison system. The proposal would tap up to $400 million from the state’s $2.2 billion share of American Rescue Plan funds to help pay for the construction. “I am pleased and extremely hopeful that we are finally positioned to address our state’s prison infrastructure challenges,” the Republican governor said in a statement last week. “While this issue was many years in the making, we stand united to provide an Alabama solution to this Alabama problem.” But critics of the plan say the state’s prison problems go beyond building conditions and that the state should not be using pandemic relief dollars to build prisons. “This week, the Alabama Legislature plans to spend $400 in American Rescue Plan funds — money intended to help your local schools, get your kids into affordable childcare, provide a lifeline to your small business, or assist your struggling rural hospital — to build two new mega-prisons. Not only is this a poor decision, it robs our communities of the money they desperately need to rebuild after 18 months of the pandemic,” said Katie Glenn, a policy associate with the SPLC Action Fund, an arm of the Southern Poverty Law Center. The Alabama prison construction proposal calls for at least three new prisons — a prison in Elmore County with at least 4,000 beds and enhanced space for medical and mental health care needs; another prison with at least 4,000 beds in Escambia County; and a women’s prison — as well as renovations to existing facilities. President Joe Biden’s sweeping $1.9 trillion COVID-19 rescue package known as the American Rescue Plan was signed in March, providing a stream of funds to states and cities to recover from the pandemic. The program gives broad discretion to states and cities on how to use the money. Republican legislative leaders said they are comfortable they can legally use the funds because the American Rescue Plan, in addition to authorizing the dollars for economic and health care programs, says states can use the money to replace revenue lost during the pandemic to strengthen support for vital public services and help retain jobs. Ivey and GOP legislative leaders have defended the use of the virus funds, saying it will enable the state to essentially “pay cash” for part of the construction and avoid using state dollars as well as paying interest on a loan. “We don’t have to borrow quite as much money and pay all that money back,” Ivey told reporters last week as she defended using virus funds for prison construction. The Department of Justice last year sued Alabama, saying the state prisons for men are “riddled with prisoner-on-prisoner and guard-on-prisoner violence.” The lawsuits came after the Justice Department issued reports describing a culture of violence and listed a litany of incidents including a prison guard beating a handcuffed prisoner in a medical unit while shouting, “I am the reaper of death, now say my name!” as the prisoner begged the officer to kill him. The department noted in a 2019 report that dilapidated conditions were a contributing factor to what it called unconstitutional conditions but emphasized that, “new facilities alone will not resolve the contributing factors to the overall unconstitutional condition of ADOC prisons, such as understaffing, culture, management deficiencies, corruption, policies, training, non-existent investigations, violence, illicit drugs, and sexual abuse.” The state has disputed the accusations from the Justice Department but has acknowledged problems with staffing and building conditions. Prison construction is the centerpiece of the special session call, but it also includes two policy changes: proposals to make retroactive both the 2013 sentencing standards and a 2015 law on mandatory supervision of released inmates. Bennet Wright, executive director of the Alabama Sentencing Commission, said they estimated that would allow up to 700 inmates to apply for reduced sentences. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Plan would use virus funds, bond issue to build new prisons

Alabama lawmakers on Wednesday began reviewing the latest prison construction proposal, a plan that would use a portion of the state’s virus relief funds to start building three new lockups. The proposal calls for three new prisons — at least a 4,000-bed prison in Elmore County with enhanced space for medical, mental, and other health care needs; another at least 4,000-bed prison in Escambia County; and a women’s prison — as well as renovations to existing facilities. The projects would be done in phases and partly funded with $400 million from the state’s $2.2 billion share of American Rescue Plan funds, a key lawmaker who drafted the proposal said. Proponents said the construction would be a partial solution to the state’s long-standing prison problems, which have drawn the scrutiny of federal regulators, but one lawmaker said it would put “old problems in new buildings” unless the state made additional reforms. The U.S. Department of Justice has sued Alabama over conditions in the state’s prisons, saying it is failing to protect male inmates from inmate-on-inmate violence and excessive force at the hands of prison staff. “It’s a part of the puzzle,” said Rep. Steve Clouse, the House budget chairman who worked on the proposal. “It will help us with overcrowding, to provide a safer environment,” said Clouse, a Republican from Ozark, who added that safer facilities should help the prison system recruit and retain employees. Lawmakers looked at the proposal in meetings this week ahead of a possible special session on prison construction. Clouse said the initial reaction was positive, but they will be taking a firmer vote count over the weekend to gauge support. However, Rep. Chris England, a Tuscaloosa Democrat, said new prisons will not “take care of the immediate humanitarian crisis in state prisons.” England said additional reforms are needed to address staffing, overcrowding, and violence. “In my opinion, until you deal with the lack of leadership in the department and the problems at Pardon and Paroles, you are just making new buildings and putting old problems in them,” England said. About a dozen friends and family members of inmates protested outside the Alabama Department of Corrections last week over conditions in state prisons that they argued will not be solved by new buildings. Angela Wells said her son died last October after being stabbed by another inmate at Easterling Correctional Facility. “When he first went there he told me, ‘Momma, I’m scared.’ I told him just keep on praying, that’s all you can do,” Wells said. The new plan comes after Gov. Kay Ivey’s plan to lease new prisons from private corrections companies fell apart when financers withdrew. Clouse said the state would own the facilities under the new plan instead of leasing them. He said using $400 million in Rescue Funds, as well as $150 million in general fund dollars, would allow the state to build the first facility without borrowing money and paying interest. The bill authorizes a bond issue of up to $785 million to pay for the rest of the construction. “This whole plan, I think, is a win-win-win for the taxpayers,” Clouse said. Ivey sent lawmakers a letter this week asking them to consider the proposal to address the state’s long-standing, yet urgent, prison infrastructure challenges.” “I do not use the word urgently lightly,” Ivey wrote, noting the state faces the possibility of federal court orders unless the problems are addressed. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Nearly 200 inmates test positive for COVID at Alabama prison

Nearly 200 inmates tested positive for COVID-19 at a state prison after officials implemented mass testing in the wake of an outbreak at the facility. The Alabama Department of Corrections said in a news release that all Elmore Correctional Facility inmates not currently exhibiting symptoms were tested last week. Out of the 960 asymptomatic inmates, 191 tested positive for COVID-19. Elmore is a medium-security prison that houses about 1,000 inmates. The prison system said the testing was done as a precautionary measure in response to a recent increase in cases at the prison. Since the pandemic began, 1,901 total cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed among inmates, and 224 of those remain active. Sixty-six inmates and three staff members have died, according to numbers provided by the prison system. The Alabama prison system suspended visitation during the pandemic and has not said when it will return. Alabama has seen a surge in COVID-19 cases fueled by the highly contagious delta variant and the state’s low vaccination rate. Case and hospitalization numbers are quickly approaching what they were at the winter peak of the pandemic. The number of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 was 2,723 on Tuesday, a figure that is nearing the previous peak of 3,087 patients on Jan. 12. There are now more patients needing intensive care than there are intensive care beds in the state. The state on Tuesday had 11 more patients in intensive care than the state had intensive care beds, according to Dr. Don Williamson, the former state health officer who now heads the Alabama Hospital Association. Many hospitals have implemented surge plans and are housing intensive care patients in other areas of the hospital. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Alabama won’t describe nitrogen execution plans for security

The Alabama prison system, citing security reasons, declined to describe the “system” it has built for nitrogen hypoxia executions and gave no timeframe for its use in carrying out death sentences. An Alabama Department of Corrections spokeswoman on Monday said she could not give an estimate for when the state would develop a protocol for the new execution method. The department also declined to describe even in general terms what it has built. “At this time, the ADOC has not produced a nitrogen hypoxia execution protocol. It would be inappropriate to speculate as to when the aforementioned protocol will be produced. Additionally, due to security concerns, the ADOC cannot provide details on the completion of the initial physical build of the nitrogen hypoxia system,” Kristi Simpson, an interim spokeswoman for the Alabama Department of Corrections, wrote in an email. The statement was a response to questions from The Associated Press, which asked for a broad description of the “physical build” of the system the state said it has completed — including whether it is a room or an apparatus in the existing death chamber — and an estimated timeframe for completing the protocol. Alabama told a federal judge last week that it has finished construction of a “system” to put condemned inmates to death using nitrogen gas, an execution method authorized by state law but never put into use. “The ADOC has completed the initial physical build on the nitrogen hypoxia system. A safety expert has made a site visit to evaluate the system. As a result of the visit, the ADOC is considering additional health and safety measures,” a lawyer for the state attorney general’s office wrote in the court filing. Alabama in 2018 became the third state — along with Oklahoma and Mississippi — to authorize the untested use of nitrogen gas to execute prisoners. Death would be caused by forcing the inmate to breathe only nitrogen, thereby depriving him or her of oxygen. Lawmakers theorized that death by nitrogen hypoxia could be a simpler and more humane execution method. But critics have likened the untested method to human experimentation since it has never been used. No state has used nitrogen hypoxia to carry out an execution, and no state has developed a protocol for its use, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. The information of the construction was disclosed in a court filing involving a lawsuit over the presence of spiritual advisers in the death chamber. Alabama currently carries out executions by lethal injection unless an inmate requests the electric chair. As lethal injection drugs became difficult to obtain, states began looking at alternative ideas for carrying out death sentences including firing squads and gas. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.