Nearly all COVID deaths in U.S. are now among unvaccinated

Nearly all COVID-19 deaths in the U.S. now are in people who weren’t vaccinated, a staggering demonstration of how effective the shots have been and an indication that deaths per day — now down to under 300 — could be practically zero if everyone eligible got the vaccine. An Associated Press analysis of available government data from May shows that “breakthrough” infections in fully vaccinated people accounted for fewer than 1,200 of more than 853,000 COVID-19 hospitalizations. That’s about 0.1%. And only about 150 of the more than 18,000 COVID-19 deaths in May were in fully vaccinated people. That translates to about 0.8%, or five deaths per day on average. The AP analyzed figures provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC itself has not estimated what percentage of hospitalizations and deaths are in fully vaccinated people, citing limitations in the data. Among them: Only about 45 states report breakthrough infections, and some are more aggressive than others in looking for such cases. So the data probably understates such infections, CDC officials said. Still, the overall trend that emerges from the data echoes what many health care authorities are seeing around the country and what top experts are saying. Earlier this month, Andy Slavitt, a former adviser to the Biden administration on COVID-19, suggested that 98% to 99% of the Americans dying of the coronavirus are unvaccinated. And CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky said on Tuesday that the vaccine is so effective that “nearly every death, especially among adults, due to COVID-19, is, at this point, entirely preventable.” She called such deaths “particularly tragic.” Deaths in the U.S. have plummeted from a peak of more than 3,400 per day on average in mid-January, one month into the vaccination drive. About 63% of all vaccine-eligible Americans — those 12 and older — have received at least one dose, and 53% are fully vaccinated, according to the CDC. While vaccine remains scarce in much of the world, the U.S. supply is so abundant, and demand has slumped so dramatically that shots sit unused. Ross Bagne, a 68-year-old small-business owner in Cheyenne, Wyoming, was eligible for the vaccine in early February but didn’t get it. He died June 4, infected and unvaccinated, after spending more than three weeks in the hospital, his lungs filling with fluid. He was unable to swallow because of a stroke. “He never went out, so he didn’t think he would catch it,” said his grieving sister, Karen McKnight. She wondered: “Why take the risk of not getting vaccinated?” The preventable deaths will continue, experts predict, with unvaccinated pockets of the nation experiencing outbreaks in the fall and winter. Ali Mokdad, a professor of health metrics sciences at the University of Washington in Seattle, said modeling suggests the nation will hit 1,000 deaths per day again next year. In Arkansas, which has one of the lowest vaccination rates in the nation, with only about 33% of the population fully protected, cases, hospitalizations, and deaths are rising. “It is sad to see someone go to the hospital or die when it can be prevented,” Gov. Asa Hutchinson tweeted as he urged people to get their shots. In Seattle’s King County, the public health department found only three deaths during a recent 60-day period in people who were fully vaccinated. The rest, some 95% of 62 deaths, had had no vaccine or just one shot. “Those are all somebody’s parents, grandparents, siblings, and friends,” said Dr. Mark Del Beccaro, who helps lead a vaccination outreach program in King County. “It’s still a lot of deaths, and they’re preventable deaths.” In the St. Louis area, more than 90% of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 have not been vaccinated, said Dr. Alex Garza, a hospital administrator who directs a metropolitan-area task force on the outbreak. “The majority of them express some regret for not being vaccinated,” Garza said. “That’s a pretty common refrain that we’re hearing from patients with COVID.” The stories of unvaccinated people dying may convince some people they should get the shots, but young adults — the group least likely to be vaccinated — may be motivated more by a desire to protect their loved ones, said David Michaels, an epidemiologist at George Washington University’s school of public health in the nation’s capital. Others need paid time off to get the shots and deal with any side effects, Michaels said. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration this month began requiring health care employers, including hospitals and nursing homes, to provide such time off. But Michaels, who headed OSHA under President Barack Obama, said the agency should have gone further and applied the rule to meat and poultry plants and other food operations as well as other places with workers at risk. Bagne, who lived alone, ran a business helping people incorporate their companies in Wyoming for the tax advantages. He was winding down the business, planning to retire, when he got sick, emailing his sister in April about an illness that had left him dizzy and disoriented. “Whatever it was. That bug took a LOT out of me,” he wrote. As his health deteriorated, a neighbor finally persuaded him to go to the hospital. “Why was the messaging in his state so unclear that he didn’t understand the importance of the vaccine? He was a very bright guy,” his sister said. “I wish he’d gotten the vaccine, and I’m sad he didn’t understand how it could prevent him from getting COVID.” Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Many still hesitate to get vaccine, but reluctance is easing

So few people came for COVID-19 vaccinations in one county in North Carolina that hospitals there now allow anyone 16 or older to get a shot, regardless of where they live. Get a shot, get a free doughnut, the governor said. Alabama, which has the nation’s lowest vaccination rate and a county where only 7% of residents are fully vaccinated, launched a campaign to convince people the shots are safe. Doctors and pastors joined the effort. On the national level, the Joe Biden administration this week launched a “We Can Do This” campaign to encourage holdouts to get vaccinated against the virus that has claimed over 550,000 lives in the U.S. The race is on to vaccinate as many people as possible, but a significant number of Americans are so far reluctant to get the shots, even in places where they are plentiful. Twenty-five percent of Americans say they probably or definitely will not get vaccinated, according to a new poll from The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. They are leery about possible side effects. They tend to be Republican, and they are usually younger and less susceptible to becoming critically ill or dying if they catch COVID-19. There’s been a slight shift, though, since the first weeks of the nation’s largest-ever vaccination campaign, which began in mid-December. An AP-NORC poll conducted in late January showed that 67% of adult Americans were willing to get vaccinated or had already received at least one shot. Now that figure has climbed to 75%. That, experts say, moves the nation closer to herd immunity, which occurs when enough people have immunity, either from vaccination or past infection, to stop uncontrolled spread of a disease. Anywhere from 75% to 85% of the total population — including children, who are not currently getting the shots — should be vaccinated to reach herd immunity, said Ali Mokdad, professor of health metrics sciences at the University of Washington School of Public Health. A little over three months after the first doses were given, 100 million Americans, or about 30% of the population, have received at least one dose. Andrea Richmond, a 26-year-old freelance web coder in Atlanta, is among those whose reluctance is easing. A few weeks ago, Richmond was leaning toward not getting the shot. Possible long-term effects worried her. She knew that an H1N1 vaccine used years ago in Europe increased risk of narcolepsy. Then her sister got vaccinated with no ill effects. Richmond’s friends’ opinions also changed. “They went from, ‘I’m not trusting this’ to ‘I’m all vaxxed up, let’s go out!’” Her mother, a cancer survivor, whom Richmond lives with, is so keen for her daughter to get vaccinated that she signed her up online for a jab. “I’ll probably end up taking it,” Richmond said. “I guess it’s my civic duty.” But some remain steadfastly opposed. “I think I only had the flu once,” said Lori Mansour, 67, who lives near Rockford, Illinois. “So I think I’ll take my chances.” In the latest poll, Republicans remained more likely than Democrats to say they will probably or definitely not get vaccinated, 36% compared with 12%. But somewhat fewer Republicans today are reluctant. Back in January, 44% said they would shy away from a vaccine. The hesitance can be seen in Alabama’s rural Winston County, which is 96% white and where more than 90% of voters backed then-President Donald Trump last year. Only 6.9% of the county’s roughly 24,000 residents are fully vaccinated, the lowest level in Alabama. Elsewhere in Alabama, health officials tried to counter problems that include reluctance in heavily Black areas where distrust of government medical initiatives runs deep. They targeted a few counties with a pro-vaccine message, especially in the old plantation region where a large percentage of the population is Black and many are poor. The campaign enlisted doctors and pastors and used virtual meetings and the radio to spread the word. Dr. Karen Landers, assistant state health officer, said the effort had positive results. For example, in Perry County, where 68% of the population of about 9,300 is Black, more than 16% of the population is fully vaccinated, among the highest levels. Officials likely will make similar efforts for other parts of the state, she said. Nationwide, 24% of Black Americans and 22% of Hispanic Americans say they will probably or definitely not get vaccinated, down from 41% and 34% in January, respectively. Among white Americans, 26% now say they will not get vaccinated. In January, that number was 31%. The Biden administration’s campaign features TV and social media ads. Celebrities and community and religious figures are joining the effort. Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds, a Republican, is trying win over the one-third of adult Iowans who will not commit to getting a vaccine by emphasizing that the shots will help return life to normal. In North Carolina’s Cumberland County, fewer than 1 in 6 residents have gotten at least one shot. Amid worries there would be an unused surplus of vaccines, Cape Fear Valley Health hospital systems opened up the shots last week to everyone 16 or older. “Rather than have doses go unused, we want to give more people the chance to get their vaccine,” said Chris Tart, a Cape Fear Valley Health vice president. “We hope this will encourage more people to roll up their sleeve.” On Wednesday, Gov. Roy Cooper, a Democrat, tweeted a video of him getting a free doughnut from the Krispy Kreme chain. Customers who show their vaccine card can get a free doughnut every day for the rest of the year. “Do it today, guys!” Cooper encouraged viewers. Nearly 36% of North Carolina adults have been at least partially vaccinated, state data show. Younger people are more likely to forgo a shot. Of those under 45, 31% say they will probably or definitely forgo a shot. Only 12% of those aged 60 and older say they will not get vaccinated. Ronni Peck, a 40-year-old mother of three from

Brighter outlook for U.S. as vaccinations rise and deaths fall

More than three months into the U.S. vaccination drive, many of the numbers paint an increasingly encouraging picture, with 70% of Americans 65 and older receiving at least one dose of the vaccine and COVID-19 deaths dipping below 1,000 a day on average for the first time since November. Also, dozens of states have thrown open vaccinations to all adults or are planning to do so in a matter of weeks. And the White House said 27 million doses of both the one-shot and two-shot vaccines will be distributed next week, more than three times the number when President Joe Biden took office two months ago. Still, Dr. Anthony Fauci, the government’s top infectious disease expert, said Wednesday he isn’t ready to declare victory. “I’m often asked, are we turning the corner?” Fauci said at a White House briefing. “My response is really more like we are at the corner. Whether or not we’re going to be turning that corner still remains to be seen.” What’s giving Fauci pause, he said, is that new cases remain at a stubbornly high level, at more than 50,000 per day. The U.S. on Wednesday surpassed 30 million confirmed cases, according to data collected by Johns Hopkins University. The number of deaths now stands at more than 545,000. Nonetheless, the outlook in the U.S. stands in stark contrast to the deteriorating situation in places like Brazil, which reported more than 3,000 COVID-19 deaths in a single day for the first time Tuesday, and across Europe, where another wave of infections is leading to new lockdowns. The gloom in Europe is compounded because the vaccine rollout on the continent has been slowed by production delays and questions about the safety and effectiveness of AstraZeneca’s shot. Public health experts in the U.S. are taking every opportunity to warn that relaxing social distancing and other preventive measures could easily lead to another surge. Dr. Eric Topol, head of the Scripps Research Translational Institute, sees red flags in states lifting mask mandates, air travel roaring back and spring break crowds partying out of control in Florida. “We’re getting closer to the exit ramp,” Topol said. “All we’re doing by having reopenings is jeopardizing our shot to get, finally, for the first time in the American pandemic, containment of the virus.” Across the country are unmistakable signs of progress. More than 43% of Americans 65 and older — the most vulnerable age group, accounting for an outsize share of the nation’s more than 540,000 coronavirus deaths — have been fully vaccinated, according to the CDC. The number of older adults showing up in emergency rooms with COVID-19 is down significantly. Vaccinations overall have ramped up to 2.5 million to 3 million shots per day. Deaths per day in the U.S. from COVID-19 have dropped to an average of 940, down from an all-time high of over 3,400 in mid-January. Minnesota health officials on Monday reported no new deaths from COVID-19 for the first time in nearly a year. And in New Orleans, the Touro Infirmary hospital was not treating a single case for the first time since March 2020. And Fauci cited two recent studies that show negligible levels of coronavirus infections among fully vaccinated health care workers in Texas and California. “I emphasize how we need to hang in there for just a little while longer,” Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said Wednesday. That’s because “the early data are really encouraging.” Nationwide, new cases and the number of people hospitalized with COVID-19 have plummeted over the past two months, though Walensky remains concerned that such progress seemed to stall in the past couple of weeks. New cases are running at more than 53,000 a day on average, down from a peak of a quarter-million in early January. That’s uncomfortably close to levels seen during the COVID-19 wave of last summer. Biden has pushed for states to make all adults eligible to be vaccinated by May 1. A least a half-dozen states, including Texas, Arizona, and Georgia, are opening up vaccinations to everyone over 16. At least 20 other states have pledged to do so in the next few weeks. Microsoft, which employs more than 50,000 people at its global headquarters in suburban Seattle, has said it will start bringing back workers on March 29 and reopen installations that have been closed for nearly a year. New York City’s 80,000 municipal employees, who have been working remotely during the pandemic, will return to their offices starting May 3. Still, experts see reason to worry as more Americans start traveling and socializing again. The number of daily travelers at U.S. airports has consistently topped 1 million over the past week and a half amid spring break at many colleges. Also, states such as Michigan and New Jersey are seeing rising cases. National numbers are an imperfect indicator. The favorable downward trend in some states can conceal an increase in case numbers in others, particularly smaller ones, said Ali Mokdad, professor of health metrics sciences at the University of Washington in Seattle. And the more contagious variant that originated in Britain has now been identified in nearly every state, he said. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Half a million dead in U.S., confirming virus’s tragic reach

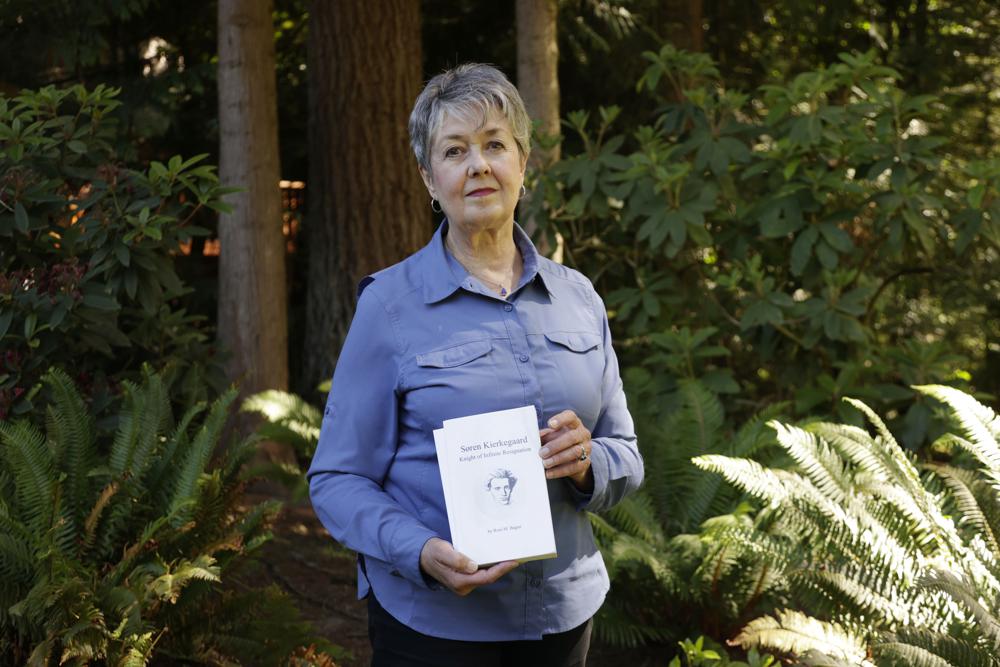

For weeks after Cindy Pollock began planting tiny flags across her yard — one for each of the more than 1,800 Idahoans killed by COVID-19 — the toll was mostly a number. Until two women she had never met rang her doorbell in tears, seeking a place to mourn the husband and father they had just lost. Then Pollock knew her tribute, however heartfelt, would never begin to convey the grief of a pandemic that has now claimed 500,000 lives in the U.S. and counting. “I just wanted to hug them,” she said. “Because that was all I could do.” Cindy Pollock poses for a portrait. (AP Photo/Otto Kitsinger) After a year that has darkened doorways across the U.S., the pandemic surpassed a milestone Monday that once seemed unimaginable, a stark confirmation of the virus’s reach into all corners of the country and communities of every size and makeup. “It’s very hard for me to imagine an American who doesn’t know someone who has died or have a family member who has died,” said Ali Mokdad, a professor of health metrics at the University of Washington in Seattle. “We haven’t really fully understood how bad it is, how devastating it is, for all of us.” Experts warn that about 90,000 more deaths are likely in the next few months, despite a massive campaign to vaccinate people. Meanwhile, the nation’s trauma continues to accrue in a way unparalleled in recent American life, said Donna Schuurman of the Dougy Center for Grieving Children & Families in Portland, Oregon. At other moments of epic loss, like the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Americans have pulled together to confront crisis and console survivors. But this time, the nation is deeply divided. Staggering numbers of families are dealing with death, serious illness, and financial hardship. And many are left to cope in isolation, unable even to hold funerals. “In a way, we’re all grieving,” said Schuurman, who has counseled the families of those killed in terrorist attacks, natural disasters, and school shootings. In recent weeks, virus deaths have fallen from more than 4,000 reported on some days in January to an average of fewer than 1,900 per day. Still, at half a million, the toll recorded by Johns Hopkins University is already greater than the population of Miami or Kansas City, Missouri. It is roughly equal to the number of Americans killed in World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War combined. It is akin to a 9/11 every day for nearly six months. “The people we lost were extraordinary,” President Joe Biden said Monday, urging Americans to remember the individual lives claimed by the virus, rather than be numbed by the enormity of the toll. “Just like that,” he said, “so many of them took their final breath alone in America.” The toll, accounting for 1 in 5 deaths reported worldwide, has far exceeded early projections, which assumed that federal and state governments would marshal a comprehensive and sustained response and individual Americans would heed warnings. Instead, a push to reopen the economy last spring and the refusal by many to maintain social distancing and wear face masks fueled the spread. The figures alone do not come close to capturing the heartbreak. “I never once doubted that he was not going to make it. … I so believed in him and my faith,” said Nancy Espinoza, whose husband, Antonio, was hospitalized with COVID-19 last month. The couple from Riverside County, California, had been together since high school. They pursued parallel nursing careers and started a family. Then, on Jan. 25, Nancy was called to Antonio’s bedside just before his heartbeat its last. He was 36 and left behind a 3-year-old son. “Today it’s us. And tomorrow it could be anybody,” Nancy Espinoza said. By late last fall, 54 percent of Americans reported knowing someone who had died of COVID-19 or had been hospitalized with it, according to a Pew Research Center poll. The grieving was even more widespread among Black Americans, Hispanics and other minorities. Deaths have nearly doubled since then, with the scourge spreading far beyond the Northeast and Northwest metropolitan areas slammed by the virus last spring and the Sun Belt cities hit hard last summer. In some places, the seriousness of the threat was slow to sink in. When a beloved professor at a community college in Petoskey, Michigan, died last spring, residents mourned, but many remained doubtful of the threat’s severity, Mayor John Murphy said. That changed over the summer after a local family hosted a party in a barn. Of the 50 who attended, 33 became infected. Three died, he said. “I think at a distance people felt ‘This isn’t going to get me,‘” Murphy said. “But over time, the attitude has totally changed from ‘Not me. Not our area. I’m not old enough,’ to where it became the real deal.” For Anthony Hernandez, whose Emmerson-Bartlett Memorial Chapel in Redlands, California, has been overwhelmed handling burial of COVID-19 victims, the most difficult conversations have been the ones without answers, as he sought to comfort mothers, fathers and children who lost loved ones. His chapel, which arranges 25 to 30 services in an ordinary month, handled 80 in January. He had to explain to some families that they would need to wait weeks for a burial. Pallbearers, who were among only 10 allowed mourners, walk the casket for internment at the funeral for Larry Hammond, who died from the coronavirus, at Mount Olivet Cemetery in New Orleans. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert) “At one point, we had every gurney, every dressing table, every embalming table had somebody on it,” he said. In Boise, Idaho, Pollock started the memorial in her yard last fall to counter what she saw as widespread denial of the threat. When deaths spiked in December, she was planting 25 to 30 new flags at a time. But her frustration has been eased somewhat by those who slow or stop to pay respect or to mourn. “I think that is part of what I was wanting,