Voter turnout sagging in troubled voting rights hub of Selma

Fewer and fewer people are voting in Selma, Alabama. And to many, that is particularly heartbreaking. They lament that almost six decades after Black demonstrators on the city’s Edmond Pettus Bridge risked their lives for the right to cast ballots, voting in predominantly Black Selma and surrounding Dallas County has steadily declined. Turnout in 2020 was under 57%, among the worst in the state. “It should not be that way. We should have a large voter turnout in all elections,” said Michael Jackson, a Black district attorney elected with support from voters of all races. Thousands will gather on March 6 for this year’s re-enactment of the bridge crossing to honor the foot soldiers of that “Bloody Sunday” in 1965. Downtown will resemble a huge street festival during the event, known as the Selma Bridge Crossing Jubilee, with thousands of visitors, blaring music, and vendors selling food and T-shirts. Another Selma event, less celebratory and more activist, was held last year by Black Voters Matter. The aim was to boost Black power at the ballot box. But the issues in Selma — a onetime Confederate arsenal, located about 50 miles (80 kilometers) west of Montgomery in Alabama’s old plantation region — defy simple solutions. Some cite a hangover from decades of white supremacist voter suppression, others a 2013 Supreme Court ruling that gutted key provisions of federal voting law to allow current GOP efforts to tighten voting rules. Some Black voters, who tend to vote Democratic, simply don’t see the point in voting in a state where every statewide office is held by white Republicans who also control the Legislature. Then there is what some describe as infighting between local leaders, and low morale in a crime-ridden town with too many pothole-covered streets, too many abandoned homes, and too many vacant businesses. All are considered factors that helped lead to a 13% decline in population over the last decade in a town where more than one-third live in poverty. Despite visits from presidents, congressional leaders, and celebrity luminaries like Oprah Winfrey — and even the success of the 2014 historical film drama “Selma” by Ava DuVernay — Selma never seems to get any better. Resident Tyrone Clarke said he votes when work and travel allow, but not always. Many others don’t because of disqualifying felony convictions or disillusionment with the shrinking town of roughly 18,000 people, he said.ADVERTISEMENT “You have a whole lot of people who look at the conditions and don’t see what good it’s going to do for them,” Clarke said. “You know, ‘How is this guy or that guy being in office going to affect me in this little, rotten town here?’” But something else seems to be going on in Selma and Dallas County. Other poor, mostly Black areas have not seen the same drastic decline in turnout. Only one of Alabama’s majority Black counties, Macon, the home of historically Black Tuskegee University, had a lower voter turnout than Dallas in 2020. Selma is hardly the only place where big Black majorities don’t always translate to big voter turnout. The U.S. Census Bureau found that a racial gap persisted nationwide in voting in 2020, with about 71% of white voters casting ballots compared to 63% of eligible Black people. A majority of Dallas County’s voters are Black, and Black people made up the largest share of the county’s vote in 2020, about 68%, state statistics show. But white voters had a disproportionally larger share of the county electorate compared to Black voters, records showed. Jimmy L. Nunn, a former Selma city attorney who became Dallas County’s first Black probate judge in 2019, said the community is weighed down by its own history. “We have been programmed that our votes do not count, that we have no vote,” said Nunn, who works in the same county courthouse where white, Jim Crow officeholders refused to register Black voters, helping inspire the protests of 1965. “It is that mindset we have to change.” Selma entered voting rights legend because of what happened at the foot of the Edmond Pettus Bridge, which is named for a onetime Confederate general and reputed Ku Klux Klan leader, on March 7, 1965. After months of demonstrations and failed attempts to register Black people to vote in the white-controlled city, a long line of marchers led by John Lewis, then a young activist, crossed the span over the Alabama River headed toward the state capital of Montgomery to present demands to Gov. George C. Wallace, a segregationist. State troopers and sheriff’s posse members on horseback stopped them. A trooper bashed Lewis’ head during the ensuing melee and dozens more were hurt. Images of the violence reinforced the evil and depth of Southern white supremacy, helping build support for the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In the following decades, Selma became a worldwide touchstone for voting rights, with then-President Barack Obama speaking at the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday in 2015. “If Selma taught us anything, it’s that our work is never done,” he said. “The American experiment in self-government gives work and purpose to each generation.” But in Selma, voting already was on the decline. After more than 66% of Dallas County’s voters went to the polls in 2008, when Obama become the nation’s first Black president, turnout fell in each presidential election afterward. Shamika Mendenhall, a mother of two young children with a third on the way, was among registered voters who did not cast a ballot in 2020. She often goes to the annual jubilee that marks the anniversary of Bloody Sunday and has relatives who participated in voting rights protests of the 1960s, and she’s still a little sheepish about missing the election. “To choose our president we ought to vote,” said Mendenhall, 25. A Black member of the county’s Democratic Party executive committee, Collins Pettaway III spends a lot of time pondering how to get young voters like Mendenhall more engaged. Older residents who remember Bloody Sunday and the subsequent Selma-to-Montgomery voting rights march vote, he said,

Renaming Alabama bridge for John Lewis opposed in Selma

Some say renaming the Edmund Pettus Bridge for John Lewis, who died Friday, would dishonor local activists who spent years advocating for civil rights before Lewis arrived in town in the 1960s.

Selma Online offers free civil rights lessons amid virus

The project attempts to show students how events in 1965 shaped voting rights.

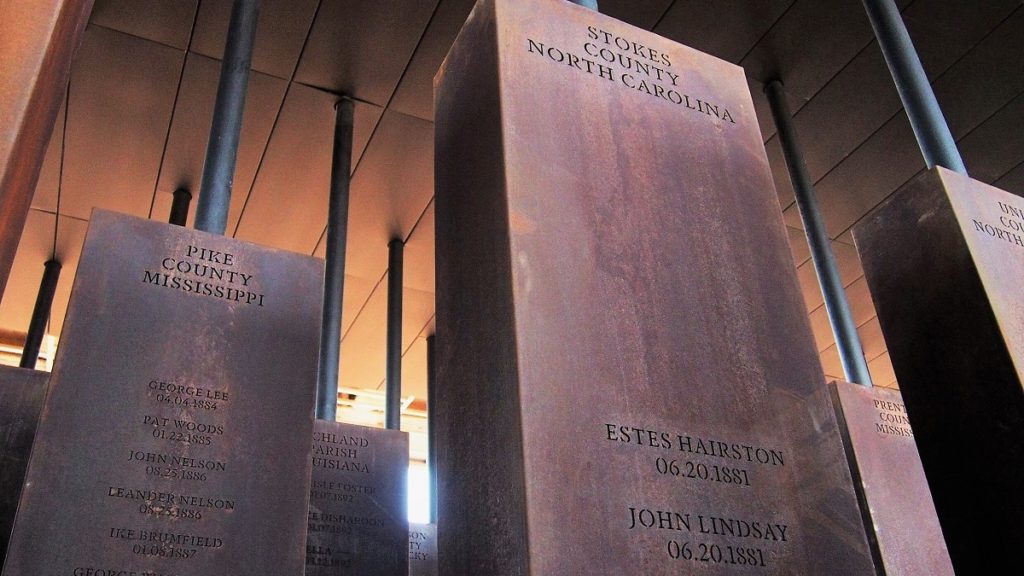

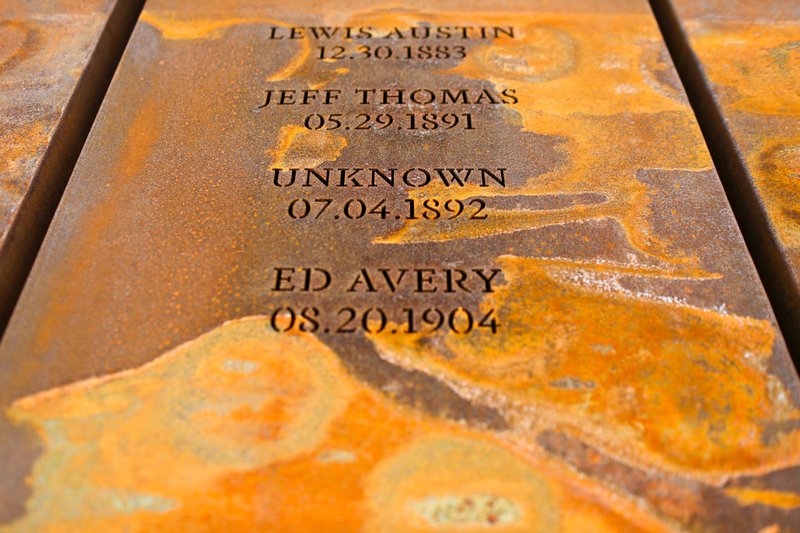

Lynching memorial may be game-changer for Montgomery tourism

A memorial to the victims of racial lynchings and a new museum in Montgomery, Alabama, have gotten a lot of attention since opening in late April. Some 10,000 people visited the memorial and museum in the first week. Tourism officials estimate they could attract 100,000 more visitors to this Southern city in the next year. One young man, Dimitri Digbeu Jr., who drove 13 hours from Baltimore to see the memorial, said he thought it had singlehandedly “rebranded” Montgomery. But tourism challenges exist. Few direct flights serve Montgomery, and it’s a three-hour drive from Atlanta. “How do we get people to come here and make the pilgrimage here?” said filmmaker Ava DuVernay at a conference marking the memorial launch. “We have to be evangelists to go out and say what you saw here and what you experienced here. … Don’t just leave feeling, ‘That was amazing. I cried.’” DuVernay, whose Oscar-nominated movie “Selma” described the 1965 civil rights march from Selma, Alabama, to Montgomery, noted that the memorial and museum were built by legal advocacy group the Equal Justice Initiative. “These people are lawyers fighting for people on death row,” DuVernay added. “They’re not thinking about how to market this to the wider world.” Some travelers say the new memorial and museum have changed their minds about visiting the Deep South. “As a black American, I’m not crazy about the idea of driving down streets named after Confederate generals and averting my eyes from Confederate flags,” said New Yorker Brian Major. “But reconciliation and peace-making has to begin somewhere and for a project as worthy and important as the lynching memorial, I would be willing to make the trip.” DuVernay put it this way: “This has to be a place where every American who believes in justice and dignity must come.” For those who do visit, here’s a guide. Lynching Memorial and Legacy Museum The National Memorial for Peace and Justice honors more than 4,000 individuals who were lynched between 1877 and 1950. Their names are inscribed on 800 steel columns, one for every U.S. county where lynchings happened. Most counties are in the South, but there are also markers for lynchings in states like Minnesota and New York. The markers begin at eye level, then gradually move overhead, evoking the specter of hanging bodies. Some of the killings are described in detail: Victims were lynched for asking for a glass of water, for voting, for testifying against a white man. The new museum, which is called The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, explores slavery and segregation in horrific detail and argues that when segregation ended, mass incarceration began. The museum cites statistics showing 300,000 people were in prison in 1971 compared with 2.3 million today, and that one in three black boys will be jailed in the 21st century if trends continue. Exhibits offer details of innocent men on death row and children imprisoned in adult facilities where they were brutalized. Montgomery resident Shawna Brannon volunteered at the opening and said visitors of all races wept and shook their heads in dismay. “Once you go through, you will never be the same,” she said. Slavery and Civil Rights The Legacy Museum is located on the site of a warehouse where thousands of enslaved people were held before being sold at auction nearby. When the Civil War began, Montgomery was the Confederacy’s first capitol. Montgomery’s Rosa Parks Museum marks the spot where a black seamstress was arrested for refusing to surrender her seat on a bus to a white passenger. That sparked a bus boycott by African-Americans that ended when the U.S. Supreme Court declared segregation on public buses unconstitutional. The bus boycott also turned a young minister named Martin Luther King Jr. into a leader of the civil rights movement. That story is told at Montgomery’s Dexter Parsonage Museum , where King and his family lived when he was pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. The parsonage porch still bears a crevice where a bomb landed (no one was hurt). Outside the Kings’ bedroom is a telephone that rang all night with threatening phone calls. The Freedom Rides Museum honors black and white students who rode Greyhound buses together to challenge segregation. A white mob attacked them when they arrived in Montgomery while police did nothing. That spurred the Kennedy Administration to send in federal marshals. Michelle Browder’s More Than Tours offers a wonderful bus tour that tells many of these stories and also shows off Montgomery’s resurgent downtown, including the restored Kress Building, now home to an art gallery and cafe. Etcetera For inexpensive, hearty lunches featuring fried chicken, turnip greens, catfish, okra and ribs, head to Davis Cafe, Farmers Market Cafe and Derk’s Filet & Vine. For a wonderful fancy dinner, try Vintage Year. Cahawba House and Shashy’s serve up great breakfasts. The Tucker Pecan store sells butter pecan ice cream and souvenir bags of pecans. Fans of country music legend Hank Williams should visit his impressive gravesite at Montgomery’s Oakwood Annex Cemetery. Downtown, the Hank Williams Museum displays the Cadillac he was riding in when he died at age 29.Montgomery’s Old Cloverdale neighborhood is home to the F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald Museum. The “Great Gatsby” writer and his wife lived here in the 1930s, and you can even rent an Airbnb apartment upstairs, complete with record player and jazz albums. Republished with the permission of the Associate Press.

Lynching memorial and museum in Alabama draw crowds, tears

Tears and expressions of grief met the opening of the nation’s first memorial to the victims of lynching Thursday in Alabama. Hundreds lined up in the rain to get a first look at the memorial and museum in Montgomery. The National Memorial for Peace and Justice commemorates 4,400 black people who were slain in lynchings and other racial killings between 1877 and 1950. Their names, where known, are engraved on 800 dark, rectangular steel columns, one for each U.S. county where lynchings occurred. A related museum, called The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, is opening in Montgomery. Many visitors shed tears and stared intently at the commemorative columns, many of which are suspended in the air from above. Toni Battle drove from San Francisco to attend. “I’m a descendant of three lynching victims,” Battle said, her face wet with tears. “I wanted to come and honor them and also those in my family that couldn’t be here.” Ava DuVernay, the Oscar-nominated film director, told several thousand people at a conference marking the memorial launch to “to be evangelists and say what you saw and what you experienced here. … Every American who believes in justice and dignity must come here … Don’t just leave feeling like, ‘That was amazing. I cried.’ … Go out and tell what you saw.” As for her own reaction, DuVernay said: “This place has scratched a scab. It’s really open for me right now.” Angel Smith Dixon, who is biracial, came from Lawrenceville, Georgia, to see the memorial. “We’re publicly grieving this atrocity for the first time as a nation. … You can’t grieve something you can’t see, something you don’t acknowledge. Part of the healing process, the first step is to acknowledge it.” The Rev. Jesse Jackson, a longtime civil rights activist, told reporters after visiting the memorial that it would help to dispel America’s silence on lynching. “Whites wouldn’t talk about it because of shame. Blacks wouldn’t talk about it because of fear,” he said. The crowd included white and black visitors. Mary Ann Braubach, who is white, came from Los Angeles to attend. “As an American, I feel this is a past we have to confront,” she said as she choked back tears. DuVernay, Jackson, playwright Anna Deavere Smith, the singing group Sweet Honey in the Rock, Congressman John Lewis and other activists and artists spoke and performed at an opening ceremony Thursday night that was by turns somber and celebratory. Among those introduced and cheered with standing ovations were activists from the 1950s Montgomery bus boycott, Freedom Rider Bernard Lafayette, and one of the original Little Rock Nine, Elizabeth Eckford. “There are forces in America today trying to take us back,” Lewis said, adding, “We’re not going back. We’re going forward with this museum.” Singer Patti Labelle ended the evening with a soulful rendition of “A Change is Gonna Come.” Other launch events include a “Peace and Justice Summit” featuring celebrities and activists like Marian Wright Edelman and Gloria Steinem in addition to DuVernay. The summit, museum and memorial are projects of the Equal Justice Initiative, a Montgomery-based legal advocacy group founded by attorney Bryan Stevenson. Stevenson won a MacArthur “genius” award for his human rights work. The group bills the project as “the nation’s first memorial dedicated to the legacy of enslaved black people, people terrorized by lynching, African-Americans humiliated by racial segregation and Jim Crow, and people of color burdened with contemporary presumptions of guilt and police violence.” Several thousand people gave Stevenson a two-minute standing ovation at a morning session of the Peace and Justice Summit. Later in the day, Edelman, founder of the Children’s Defense Fund, urged the audience to continue their activism beyond the day’s events on issues like ending child poverty and gun violence: “Don’t come here and celebrate the museum … when we’re letting things happen on an even greater scale.” Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.