Daniel Sutter: Are we running out of resources?

Thanksgiving began as a celebration of Nature’s bounty. Nature’s bounty includes natural resources. Despite reports to the contrary, Cato Institute research demonstrates that we still have plenty of natural resources. Human ingenuity and nature’s generosity explain why. That we must run out of oil, natural gas, and other resources seems obvious. Since we cannot manufacture deposits of oil, copper, zinc or other resources, these must surely get used up one day, right? News stories repeat this refrain. Fifteen years ago, news abounded of the end of cheap oil. We appeared to be running out of oil and natural gas during the energy shortages of the 1970s. Oil reserves were supposed to be gone by 2013. Yet we still have plenty of energy and minerals; U.S. oil production hit an all-time high in 2018. What happened? I’ll consider two factors. Reported resource reserves are proven reserves, or deposits of a known location, size, and quality. Dividing proven reserves by annual use gives the number of years of oil, copper, or whatever remaining. We have an estimated 53 and 46 years of oil and copper left. Proving the location and quality of reserves takes work. As economist M. A. Adelman emphasized, proven reserves are produced. Investing in proving reserves not needed for 100 years will lose money. We have found only a tiny fraction of the resources estimated to be in the Earth’s crust. New reserves will be found as existing ones are used. We might have 50 years of reserves remaining for decades. New and better methods of extraction increase effective reserves. Horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing have unlocked shale oil deposits. Earlier steam injection increased production from existing fields. Second, things only become resources when people figure out how to use them to produce goods and services. Saudi Arabia’s oil deposits generated no wealth for centuries. Knowledge is the ultimate source of value in our economy, and the mind is the source of knowledge. As economist Julian Simon put it, humans are the “ultimate resource.” Usually more than one formula or process can produce a good. When we are cooking, we can usually substitute for a missing ingredient and produce a tasty dish. We can use less of a resource if needed, or substitute something else; in the 1800s, people switched from whale oil to kerosene for lighting homes. We need not run out of resources because we can use alternatives if s specific mineral or fossil fuel runs out. Because reserves poorly measure resource availability, Cato’s index uses prices instead. Economic theory tells us that prices should reflect the best guesses concerning future discoveries, improvements in extraction, and emerging substitutes. If we are truly running out of something, its price should increase sharply. This was the basis for Julian Simon’s bet with Stanford University biologist Paul Ehrlich. In 1980, Simon let Ehrlich pick five resources that he thought were most likely to become depleted. Ehrlich selected chromium, copper, nickel, tin and tungsten; by September 1990, the prices had fallen and Simon won. The new Cato measure is accordingly called the Simon Abundance Index and uses fifty commodity and resource prices. Price comparisons over time require adjustment, most importantly for inflation. But since earnings rise in a growing economy, the Index also adjusts for income. This puts commodity prices in terms of time, say the number of hours of work required to buy ten gallons of gas. Simon Index prices fell 65 percent between 1980 and 2017 adjusting for inflation and earnings. When adjusting only for inflation, prices fell 36 percent. Over these years, world population increased by more than three billion persons. Markets found enough new reserves to accommodate population growth. Limits exist to Nature’s bounty, our ability to harvest this bounty, and for substitutes for resources. And we must consider fossil fuels’ impacts on pollution and climate change. Still, the Simon Index shows that we are not running out of resources. Because knowledge creates natural resources, we can potentially maintain a growing economy for generations to come. Daniel Sutter is the Charles G. Koch Professor of Economics with the Manuel H. Johnson Center for Political Economy at Troy University and host of Econversations on TrojanVision. The opinions expressed in this column are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of Troy University.

J. Pepper Bryars: Like Chilton County’s peach trees, Alabama’s occupational license laws need regular pruning

Motorists who travel I-65 between Birmingham and Montgomery during summertime often enjoy the tradition of stopping in Clanton for a freshly-picked basket of Chilton County’s famous peaches. There’s something special about that part of Alabama, a Goldilocks zone that produces those thick, juicy, tasty treats. Not too cold. Not too hot. Just right. Well, that and an awful lot of pruning. Thing is, peach trees need to be cut back annually so that they can continually produce the best and most fruit. A snip here. A lop there. Just planting them and walking away isn’t enough. Kind of like laws, and there’s no better example of such a thing than those governing occupational licensing in Alabama. When we first began planting them decades ago, occupational licensing laws were meant to ensure that those who were practicing potentially dangerous professions were doing so safely. Those early measures covered around 5 percent of the U.S. labor force, according to a recent policy memo from the Cato Institute. But like an untended peach tree, they’ve been left to grow wild. “Alabama licenses a total of 151 occupations, covering over 432,000 Alabama workers, which represents over 21 percent of the state’s labor force,” wrote the authors of The Costs of Occupational Licensing in Alabama, a special report commissioned by the Alabama Policy Institute. The report found that the initial costs of occupational licensing are $122 million, with another $45 million for renewals plus $243 million in annual continuing education costs. Those costs are eventually passed along to consumers. Clearly, these laws are due for pruning, but Alabama’s lawmakers have taken an uneven approach to the orchard lately. Near the end of the last legislative session they passed a bill that doubled the license application for landscape architects to $150 and increased the maximum fine that could be imposed on them for violations from $250 to $2,500 per instance. But they allowed a bill to die that would have reformed the Alabama Sunset Committee, the body responsible for periodically reviewing state professional licensing boards, agencies, and commissions to ensure they’re operating effectively and ethically. The bill would have added a “sunrise” provision to the process so that when a new licensing requirement is proposed, lawmakers would have an objective set of thorough standards to judge its merits, like if licensing would create an unreasonable effect on job creation or place unreasonable access or restrictions on those seeking to enter the profession. Proponents would have also needed to demonstrate how the public would be harmed without the licensing measure, and how we couldn’t be protected by other means. In other words, it would have to be more about protecting the people than protecting the profession, used only as a last resort, and even then, it would be applied to the least degree possible, but the bill failed to even get a public hearing. Lawmakers did manage to do a little pruning, though, by providing a path to occupational licensing once denied to former convicted felons. “For people who have served their full sentence … they should be able to get a job to feed their family, contribute to society, and lessen the chance that they fall back into crime,” wrote State Sen. Cam Ward, Republican-Alabaster, who sponsored the reform. Former convicts can now petition a judge for an order of limited relief, which prohibits an occupational licensing board from automatically denying their application. “The board or commission must give the case a fair hearing,” Ward said, adding that the new law “recognizes the dignity of work.” Some of Alabama’s occupational licensing laws are good. Some are bad. But most are just in need of some regular pruning. Let’s hope our lawmakers bring a good pair of garden shears to next year’s legislative session so that Alabama’s laws, like Chilton County’s peach trees, can produce the best fruit. Pepper Bryars is a senior fellow at the Alabama Policy Institute and host of the 1819 podcast. Follow him on Twitter at @jpepperbryars. API is an independent, nonpartisan, nonprofit research and educational organization dedicated to strengthening free enterprise, defending limited government, and championing strong families. If you would like to speak with the author, please e-mail communications@alabamapolicy.org or call (205) 870-9900. Permission is hereby granted to display, distribute, and quote from this publication, provided that it is properly attributed to the Alabama Policy Institute and the author. For editorial questions, please contact communications@alabamapolicy.org.

J. Pepper Bryars: It’s time to reform occupational licensing in Alabama

Did you know that it’s against the law to braid hair, wash hair, or even plant flowers professionally in Alabama without a license? That’s because occupational licensing, originally meant to protect consumers, has gotten way out of hand. A video recently produced by the Alabama Policy Institute illustrates just how ridiculous it has become. Sure, licensing certain occupations is a good thing. We need to know our builders, physicians, attorneys, and those practicing many other specialized and potentially dangerous professions are being well regulated. But the process has evolved beyond its original intent. Sometimes, it seems to be more about controlling the market and restricting access to competition rather than public safety. “Alabama licenses a total of 151 occupations, covering over 432,000 Alabama workers, which represents over 21 percent of the state’s labor force,” wrote the authors of The Costs of Occupational Licensing in Alabama, a special report commissioned by API. The report found that the initial costs of occupational licensing are $122 million, with another $45 million for renewals plus $243 million in annual continuing education costs. Those costs are eventually passed along to the consumers. Thankfully, we have an opportunity to at least slow further growth of occupational licensing in Alabama. State Rep. Randall Shedd, Republican-Fairview, has introduced House Bill 88, known as the Alabama Sunrise Act. Under existing law, the Alabama Sunset Committee is responsible for periodically reviewing state professional licensing boards, agencies, and commissions to ensure they’re operating effectively and ethically. Shedd’s bill would reform the committee’s processes by adding a “sunrise” provision so that when a new licensing requirement is proposed, lawmakers would have an objective set of thorough standards to judge its merits. The bill states that “no profession or occupation be subject to regulation by the state unless the regulation is necessary to protect the public health, safety, or welfare from significant and discernible harm or damage and that the police power of the state (is exercised only to the extent necessary for that purpose.” In other words, it would have to be more about protecting the people than protecting the profession, used only as a last resort, and even then it would be applied to the least degree possible. The bill sets down several requirements that a proposal must satisfy before a new license is created, including: Demonstrate that it wouldn’t have an unreasonable effect on job creation or job retention, or place unreasonable access or restrictions on the ability of individuals whoare practicing the profession. Explain why the public cannot be effectively protected by other means. And provide documentation of the nature and extent of the harm to the public caused by the unregulated practice of the profession or occupation. Unless we do something now, we should expect the trend to continue. “In the past six decades, instances of occupational licensing in the United States have increased from a coverage of around 5 percent of the U.S. labor force to a present-day coverage of close to 25 percent of the U.S. labor force,” wrote Peter Q. Blair and Bobby W. Chung in a recent policy memo from the Cato Institute. Those pushing for additional occupational licensing may have the best of intentions, but we should remind them of the simple phrase uttered by a Frenchmen more than 200 years ago. His words captured the essence of the free market and became the slogan for an emerging economic doctrine that formed the bedrock of America’s prosperity. When a meddling advisor to King Louis XIV asked a group of struggling businessmen in Paris how the government could help them increase profits, a frustrated factory owner named Legendre bravely shouted, “Laissez-nousfaire!” Translation: “Leave us alone!” Contact your state lawmaker today and tell them you want some of the boards to simply leave us alone and that the Alabama Sunrise Act should receive a public hearing before the House Boards Agencies and Commissions Committee, and soon. J. Pepper Bryars is a senior fellow at the Alabama Policy Institute. Follow him on Twitter at @jpepperbryars.

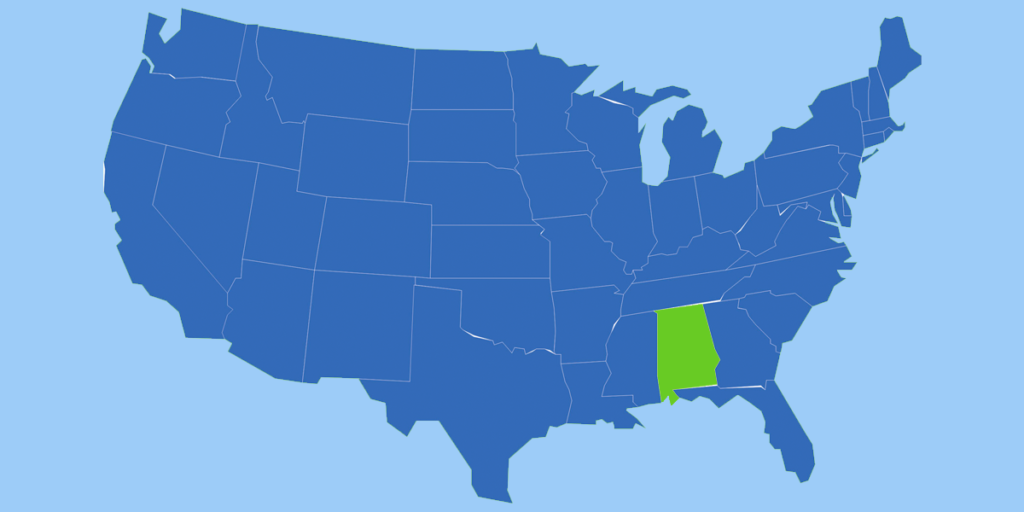

New study ranks Alabama as the 28th freest state in America

America may be the land of the free, but apparently the same can’t be said about Alabama. In a new study released Tuesday by the Cato Institute — a libertarian think tank dedicated to the principles of individual liberty, limited government, free markets, and peace — Alabama was ranked the 28th freest state in the nation. By individual category, Alabama scores 19th in fiscal policy, 23rd in regulatory policy, and 49th in personal freedom. The study, Freedom in the 50 States, ranks each U.S. state by how its public policies promote freedom in the fiscal, regulatory, and personal freedom spheres. To determine these rankings, authors William Ruger and Jason Sorens examined state and local government intervention across a range of more than 230 policy variables — from taxation to debt, eminent domain laws to occupational licensing, and drug policy to educational choice. According to the study: As a socially conservative Deep South state, it is unsurprising that Alabama does much better on economic freedom than on personal freedom. But three of its four neighbors do substantially better on economic freedom (Florida, Tennessee, and Georgia), with only Mississippi doing worse. Alabama’s overall freedom level has remained essentially flat since year-end 2014, while it has improved a bit since 2000 even in terms of non-federalized policies. Alabama has always been one of the lowest taxed states in the country. Its combined state and local tax collections, excluding motor fuel and severance, were an estimated 8 percent of adjusted personal income in fiscal year 2017. Alabama’s debt burden is also fairly low compared to other states. On regulatory policy, Alabama does especially well on land-use and labor policy. In fact, it scores first in that area. However, it does well below average on its tort system and certain cronyist policies. Indeed, it ranks 35th in the cronyism index. The state is one of the worst in the country on personal freedom, despite benefiting from the Supreme Court’s Obergefell decision. Other factors keeping its personal freedom score low include high beer and spirit taxes, above-average wine taxes and a ban on direct wine shipment, and harsh cannabis laws where it is possible to receive life imprisonment for a single marijuana trafficking offense. To improve on its freedom rankings, the authors suggest several remedies, including: encouraging the privatization of hospitals and utilities to bring government employment down closer to the national average. Private utility monopolies will, however, require careful rate regulation; improving the civil liability system by tightening or abolishing punitive damages and abolishing joint and several liability; reducing its incarceration rate with thorough sentencing reform, including abolishing mandatory minimums for nonviolent offenses and lowering maximum sentences for marijuana offenses and other victimless crimes. “Measuring freedom is important because freedom is valuable to people,” write Ruger and Sorens. “State and local governments ought to respect basic rights and liberties, such as the right to practice an honest trade or the right to make lifetime partnership contracts, whether or not respecting these rights ‘maximizes utility.’ Even minor infringements on freedom can erode the respect for fundamental principles that underlie our liberties. This index measures the extent to which states respect or disrespect these basic rights and liberties; in doing so, it captures a range of policies that threaten to chip away at the liberties we enjoy.”

Daniel Sutter: Driverless cars and public transit

The first driverless car pedestrian fatality occurred recently in Arizona, almost two years after the first fatal crash. These tragic fatalities signal the ongoing development of this technology. Cars and trucks with drivers killed 5,800 pedestrians in 2016, so a driverless car pedestrian fatality was probably inevitable. Driverless cars will reshape our economy, as 2.8 million people currently work in transportation. One area of disruption which has flown under the radar is public transportation. A new Cato Institute study, “The Coming Transit Apocalypse,” highlights the looming wreck. How can we be sure that driverless vehicles will be on the road soon? Nothing is certain in life, but the Cato study notes that more than three dozen companies worldwide are experimenting with the technology, including auto makers, auto parts suppliers, and tech companies. Thus many companies believe that practical self-driving vehicles are within reach. Given that these companies are trying different approaches, it seems likely that at least one successful design will emerge. Public transportation is already hemorrhaging riders, with a 3 percent decline in the first half of 2017 following a 4.4 percent decline between 2014 and 2016. Seven metro transit systems have seen ridership declines of at least 27 percent since 2009. Although lower gas prices partly explain this, ride sharing services like Uber and Lyft are also having an impact. Ride sharing offers greater convenience than transit with door-to-door, on-demand service, but is currently more expensive. Driverless, shared vehicles are projected to be price competitive with transit. Consequently, the Cato study contends that public transit will be “extinct” everywhere outside of New York City and perhaps a couple of other markets by 2030. Mass transit has never been very popular since the widespread ownership of cars, and currently carries less than one percent of travelers in all but a few cities. One disadvantage of mass transit is geography: residents and jobs are too spread out in most American cities to generate high enough demand for either buses or trains on centralized routes. Culture also plays a factor, as many Americans simply prefer driving. Low ridership rates are not due to a lack of government spending, which has exceeded $1 trillion (adjusted for inflation) since 1970. Fares cover only about 30 percent of expenditures. Americans will not use even highly subsidized public transport. Many transit agencies have deferred maintenance on rail systems, which have a useful life of about 30 years before requiring substantial rebuilding. Washington’s Metro system turned 30 in 2006, and by 2013, incidents of smoke in tunnels were causing evacuations twice a month. Unreliable service makes transit less competitive with ride sharing going forward. An end of public transport, however, will not end taxpayers’ costs. Many systems went into debt building or repairing subway or rail lines, while others have significant unfunded health care and pension liabilities. For example, the Cato study estimates that Boston’s transit system has $3.4 billion in unfunded liabilities, which represent a portion of employees’ compensation. Transit systems have spent lavishly on new rail lines instead of ensuring that promises to employees will be kept. Regardless of exactly how quickly self-driving cars take over, further investments in transit infrastructure do seem dubious at this time. Nonetheless, Los Angeles County decided in 2016 to spend $120 billion, primarily on new light rail lines. The Cato study suggests that new rail lines being planned now will be obsolete before finished. Only government agencies spending our tax dollars can afford to be so short-sighted. The potential transit apocalypse illustrates a recurrent problem. Once political support for spending coalesces, government finds adjusting to changing economic and societal conditions difficult. Mounting losses do not cause proponents to sour on mass transit. Economist Mancur Olson claimed that the entrenchment of programs under democracy produced stagnation. Public transportation has helped many Americans, particularly those who could not afford cars. Changing conditions, however, require policy changes. I fear that we will still be building subways even after everyone has their own automated chauffer. ••• Daniel Sutter is the Charles G. Koch Professor of Economics with the Manuel H. Johnson Center for Political Economy at Troy University and host of Econversations on TrojanVision. The opinions expressed in this column are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of Troy University.

Robert Bentley receives failing grade on fiscal conservatism

Alabama Gov. Robert Bentley has had a rough year plagued with scandal and an ongoing impeachment probe, and now his lack of fiscal restraint is earning him poor marks on a nationwide report card of governors. According to the right-leaning libertarian Cato Institute‘s 2016 “Fiscal Policy Report Card on America’s Governors,” Bentley has become one of the least fiscally responsible governors in the country. The biennial report assigns governors grades of A to F, based on their tax and spending policies. The 2016 report looked at data from January 2014 to August 2016. Bentley, who ran on fiscal conservatism in both his 2010 and 2014 gubernatorial campaigns, was one of only 10 governors to receive an F rating, most of whom (seven), are Democrats. According to the report, Bentley dropped from a B in the last report card to an F in this one due to his support of major tax increases. “In his first few years in office, Bentley generally opposed tax increases, but in 2015 he made a U-turn,” the report said. “He proposed a tax increase of more than $500 million a year, including increases on businesses, cigarettes, automobile sales, automobile rentals, and other items.” “The governor’s plan was opposed by the Legislature, but after months of wrangling, they reached a compromise on a $100 million tax package. Bentley signed into law a cigarette tax increase of 25 cents per pack, and higher taxes and fees on nursing facilities, prescriptions, and the insurance industry. In 2016 Bentley supported a gasoline tax increase, but that legislation did not pass.”