A swing state no more? GOP confidence grows in Florida

Democrats are increasingly concerned that Florida, once the nation’s premier swing state, may slip away this fall and beyond as emboldened Republicans capitalize on divisive cultural issues and population shifts in crucial contests for governor and the U.S. Senate. The anxiety was apparent last week during a golf cart parade of Democrats featuring Senate candidate Val Demings at The Villages, a retirement community just north of the Interstate 4 corridor. It was once a politically mixed part of the state where elections were often decided, but now some Democrats now say they feel increasingly isolated. “I am terrified,” said 77-year-old Sue Sullivan, lamenting the state’s rightward shift. “There are very few Democrats around here.” In an interview, Demings, a congresswoman and former Orlando police chief challenging Republican Sen. Marco Rubio, conceded that her party’s midterm message isn’t resonating as she had hoped. “We have to do a better job of telling our stories and clearly demonstrating who’s truly on the side of people who have to go to work every day,” she said. The frustration is the culmination of nearly a decade of Republican inroads in Florida, where candidates have honed deeply conservative social and economic messages to build something of a coalition that includes rural voters and Latinos, particularly Cuban Americans. Donald Trump’s win here in 2016 signaled the evolution after the state twice backed Barack Obama. And while he lost the White House in 2020, Trump carried Florida by more than 3 percentage points, a remarkable margin in a state where elections were regularly decided by less than a percentage point. President Joe Biden will visit the state on November 1, exactly one week before Election Day, to rally Democrats. Demings said she’s had two conversations with the president about campaigning together, but she could not confirm any joint appearances. And Charlie Crist, the Democratic nominee for governor, said he would attend a private fundraiser with Biden on the day of the rally, but he wasn’t sure whether they would appear together in public. “If we could squeeze in a little public airtime, that’d be a wonderful thing I would welcome,” Crist said in an interview. Still, the GOP is bullish that it can keep notching victories, even in longtime Democratic strongholds. Some Republicans are optimistic the party could carry Miami-Dade County, a once unthinkable prospect that would virtually eliminate the Democrats’ path to victory in statewide contests, including presidential elections. And in southwest Florida’s Lee County, a major Republican stronghold, not even a devastating hurricane appears to have dented the GOP’s momentum. In fact, Republicans and Democrats privately agree that Hurricane Ian, which left more than 100 dead, may have helped Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis broaden his appeal. On Monday, he’ll participate in a debate against Crist in which he’ll likely highlight his stewardship of the state during a searing crisis. But the 44-year-old Republican governor has spent much of his first term focused on sensitive social issues. He’s signed new laws banning abortions at 15 weeks of pregnancy with no exceptions for rape or incest, along with blocking critical race theory and LGBTQ issues from many Florida schools. He has also stripped millions of dollars from a major league baseball team that spoke out against gun violence and led efforts to eliminate Disney’s special tax status for condemning his so-called “Don’t Say Gay” bill. On the eve of the hurricane, DeSantis shipped dozens of Venezuelan immigrants from Texas to Martha’s Vineyard to call attention to illegal immigration at the U.S.-Mexico border. Crist, a former congressman and onetime governor himself, acknowledged some voters “dig” DeSantis’ focus on cultural issues, “but most Floridians are good, decent people.” He noted that at least one Hispanic radio host has compared DeSantis to former Cuban dictator Fidel Castro. “Customarily, when you come out of a primary, people will move to the middle. He’s clearly not doing that, to say the least,” Crist said of his Republican rival. But to the horror of many Democrats, DeSantis could become the first Floridian to win a governor’s race by more than 1 point since 2006. That kind of showing might lift Rubio in the U.S. Senate election while helping the GOP win as many as 20 of the state’s 28 U.S. House seats. Should DeSantis win big as expected, his allies believe he would have the political capital to launch a successful presidential campaign in 2024 — whether Trump runs or not. “It’s shocking, and it’s scary,” state Democratic Party Chair Manny Diaz said about DeSantis’ repeated willingness to use the power of his office to attack political rivals, whether individual opponents or iconic corporations like Disney. DeSantis, who declined an interview request, has found success by bucking the conventional wisdom before. He beat Democrat Andrew Gillum four years ago by 32,436 votes out of more than 8.2 million cast, a margin so narrow that it required a recount. But in the four years since then, Republicans have erased a voter registration advantage that Florida Democrats had guarded for decades. When registration closed for the 2018 election, Democrats enjoyed a 263,269-vote advantage. As of September 30, Republicans had a lead of 292,533 voters — a swing of nearly 556,000 registered voters over DeSantis’ first term. “We’re no longer a swing state. We’re actually annihilating the Democrats,” said Florida GOP Chairman Joe Gruters, a leading DeSantis ally. And while he says his party has focused on traditional kitchen-table issues, such as gas prices and inflation, Gruters leaned into cultural fights — especially the Florida GOP’s opposition to sexual education and LGBTQ issues in elementary schools — that have defined DeSantis’ tenure. “I don’t want anyone else teaching my kids about the birds and the bees and gender fluidity issues,” Gruters said. Strategists in both parties believe Florida’s political shift is due to multiple factors, but there is general agreement that Republicans have benefited from an influx of new voters since DeSantis emerged as the leader of the GOP resistance to the pandemic-related public health measures. Every day on average over the year between 2020 and 2021, 667 more people

Todd Carney: Florida primary races to watch

The results of the Florida primaries, which will take place on August 23, will likely have a major impact on the midterms and on the political landscape. Florida Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis will likely win reelection in November, but Democrats are seriously contesting the governorship. Democrats’ two major candidates are agriculture commissioner Nikki Fried and Congressman Charlie Crist, a former governor. Fried has faced ethical questions, has run an erratic campaign, and lags in the polls. Crist, who has been in politics for 30 years, has lost runs for statewide office twice in a row and last won an office statewide 16 years ago. It’s not clear who the better general election candidate would be. Fried is a fresh face and has won statewide more recently than Crist, but her far-left positions and scandals have hurt her. Crist is more moderate and came close to winning the governorship in 2014, but his reelection victory for Congress in 2020 was underwhelming, and many consider him a washed-up perennial candidate. DeSantis looks pretty certain to beat either one, but DeSantis’s reelection margin could influence his standing as a potential presidential candidate. In the race for Florida’s first congressional district, Congressman Matt Gaetz is the incumbent. The federal government has been conducting a sex-trafficking investigation into Gaetz. He has one main challenger, Mark Lombardo, a businessman, and veteran. Gaetz has spent about $5 million more than Lombardo. Despite his ethical issues, if Gaetz wins the primary, he will likely win the general election. A Lombardo victory, on the other hand, would free Republicans of Gaetz as a problem. Congresswoman Kat Cammack represents Florida’s third congressional district. Cammack is a rising star who had no problems until a few weeks ago when she compared opponents of gay marriage to racists. But Cammack has a significant funding advantage and high-profile endorsements. If she loses, it will demonstrate again the potency of cultural issues. If she wins, she could position herself for a later run at higher office. Florida’s seventh district has four main Republican candidates: businessman and veteran Cory Mills, state representative and National Guard officer Anthony Sabatini, former congressional aide Rusty Roberts, and pastor and veteran Brady Duke. Mills has led most polls and has received endorsements from classic conservative figures. Sabatini is very controversial and has secured endorsements from far-right figures. The race is likely to go Republican, but if Sabatini gets the nomination, he could put the seat at risk this November. Crist gave up his seat in the 13th district to run for governor and redistricting made it more Republican. Businesswoman and veteran Anna Paulina Luna has led most polling, raised lots of money, and has prominent endorsements. Luna is also a telegenic Latina, so if she wins, she will likely have a bright future in the GOP. Attorney Kevin Hayslett is running and has received support from several local politicians. Attorney and former congressional aide Amanda Makki is running as well. She is also telegenic and has a fascinating personal story – she fled Iran due to oppression. So she could become a prominent figure if she wins. Florida has a new seat, the 15th district, up for election. All media outlets rate it as “likely Republican.” State representative Jackie Toledo is a conservative Latina who will likely become a significant voice in the GOP if she wins. Former secretary of state Laurel Lee has raised a substantial sum of money and enjoys the backing of prominent party officials. As a charismatic female, she could also gain a high profile if she wins. State senator Kelli Stargel is also running and received endorsements from some local officials. Veterans Kevin McGovern and Demetries Grimes have raised money effectively as well and could be competitive. Florida’s primaries could decide control of the House of Representatives or at least play a significant role in the margins of a Republican majority, should the party win one. The state’s primaries could also help shape the future look of the Republican caucus. And finally, the primaries could serve to help or hinder DeSantis’s likely presidential ambitions. Todd Carney is a lawyer and frequent contributor to RealClearPolitics. He earned his juris doctorate from Harvard Law School. The views in this piece are his alone and do not reflect the views of his employer. Republished with the permission of The Center Square.

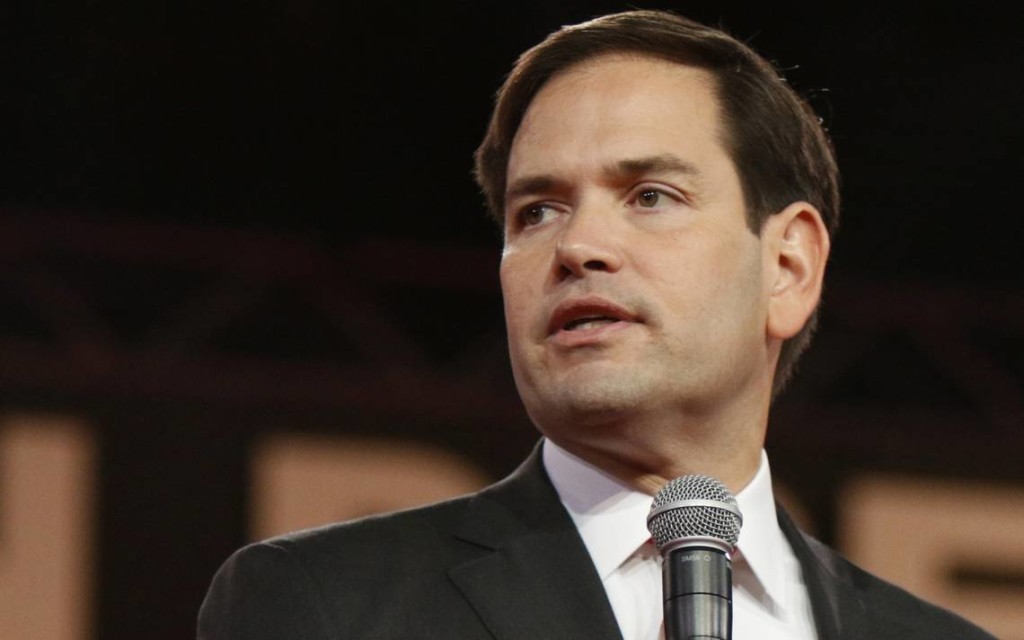

Jac VerSteeg: Political fratricide model fails Marco Rubio

Marco Rubio was convinced the Fratricide Model of politics was his ticket to the top. Now, after one brilliant win and one spectacular loss, the Florida senator claims to have renounced the model. He will not, he says, run for governor in 2018. Florida Agriculture Commissioner Adam Putnam need not fear a Rubio challenge. We won’t have Marco Rubio to kick around anymore? Political fratricide worked for Rubio in 2010 when he broke in line to oppose and defeat Gov. Charlie Crist for a U.S. Senate seat. He was helped along by that year’s Tea Party revolt and the fact that newly Independent Crist and Democrat Kendrick Meek split the no-to-Rubio vote. Just as angry as the 2010 Tea Party faithful but with a new idol, Florida GOP primary voters this month delivered the final blow to Rubio’s second attempt at exploiting the Fratricide Model. They gave Donald Trump a victory in every county except Rubio’s Miami-Dade refuge. What effect did Rubio’s fratricidal challenge to his mentor (and his better) Jeb Bush have on the contest? What if Rubio had shown respect, bided his time and supported Bush? No way to know, but Florida might have been the firewall for Bush and the anti-Trumpers that it so dismally failed to be for Rubio. I do not think that every intra-party challenge can be characterized as an example of the Fratricide Model. It’s appropriate for rivals in the same party to let voters decide between them. But when one of the challengers has not earned the right to vie for an office and, further, damages the party or the office he seeks, that is political fratricide. And that is what Rubio has done. He knocked off Crist – once a Republican rising star – and proceeded to disdain the Senate seat he won. As a result, the seat easily could go to a Democrat this November. Then, of course, Rubio challenged Jeb. After helping to undermine the clear choice of the GOP establishment, Rubio proceeded to run a horrible campaign. The overall effect boosted Trump’s prospects and hurt the Republican Party. What will Rubio do next? He claimed, upon returning to work in the Senate – if someone so often a no-show can be said to “return to work” – that, in addition to eschewing a gubernatorial bid, he would not be anybody’s veep. You never know what to make of a politician’s claim that he won’t seek this or that office. How many times did now-House Speaker Paul Ryan claim that he would not accept the post? (By the way, Ryan also insists he won’t allow himself to be nominated at a fractured GOP convention this summer. Right.) For Rubio, who has been assailed for overweening ambition, what better strategy than to affect a new humility and express no ambition whatsoever for political office? Is it really believable that if, by some miracle, he emerges as a vice presidential candidate – perhaps for Ryan at a brokered convention – Rubio would turn down the chance? It is more believable that Rubio does not plan to run for governor in 2018. Not because he doesn’t lust after political office, but because he was so badly burned this year by the Fratricide Model. Even Rubio should be able to see that he is less qualified and less deserving than the premier GOP candidate for the job, Putnam. Putnam served in the Florida Legislature and then went on to serve in Congress for 10 years. Unlike Rubio, Putnam actually performed his job diligently and rose to be the third-highest ranking Republican in the U.S. House. Then, rather than stay in a secure seat in federal office, Putnam chose to return to state politics and has been elected and re-elected as Ag commissioner. It is worth emphasizing that Putnam’s chosen trajectory brought him voluntarily back to Florida. Rubio’s chosen path was to attempt to move into the White House. Only a failure to reach that goal could bring him the “consolation prize” of a gubernatorial campaign. And even if he were elected governor, he would just treat it as a stepping stone back onto the national stage. Could Rubio beat Putnam? Considering his drubbing on the Ides of March, the likely answer is no. His decision not to run for governor easily could be a case of sour grapes rather than an example of his newfound humility. Since Rubio decided to give up his Senate seat, it is hard to see any political path that puts him back on that stage. His best option? Hope that anybody but Trump wins and that Rubio could find a spot in a Ted Cruz or John Kasich administration and bide his time. But does anyone think that if Rubio saw a chance to return to political prominence he would hesitate to seize it even if it meant running over one of his Republican brethren? Oh, brother. *** Jac Wilder VerSteeg is a columnist for The South Florida Sun Sentinel, former deputy editorial page editor for The Palm Beach Post and former editor of Context Florida.

Darryl Paulson: The rise and fall of Marco Rubio

Marco Rubio has had a meteoric political career. From winning a seat on the West Miami City Council in the 1990s, to winning a special election by 64 votes to earn a seat in the Florida House, to his stunning victory over Republican Gov. Charlie Crist in the 2010 U.S. Senate race, Rubio’s political career has been impressive. When Rubio challenged the popular Crist for the Republican nomination to the U.S. Senate, most pundits said he didn’t have a chance. Crist had the support of the Republican establishment in Florida and also the support of the Republican Senatorial Campaign Committee. Rubio started the race trailing Crist by anywhere between 30 to 45 percent. Rubio, playing the role of the biblical David to perfection, defeated the Goliath Crist. In what I consider the most astounding election in modern Florida history, Rubio chased Crist from the Republican Party and forced him to run as an independent candidate. On Election Day, Rubio won 49 percent of the vote to 30 percent for Crist and only 20 percent for Democrat Kendrick Meek. The giant had been slain, and Rubio would soon be branded by Time magazine as “the Republican savior.” After losing the 2012 presidential election, the Republican Party created a “Growth and Opportunity Program” to analyze the results and develop a path forward. Essentially, the committee recommended that the party had to broaden its appeal to women and minorities, especially Hispanics, if they hoped to win the White House. They could no longer win with just white, male voters. Many Republicans viewed Rubio as the future face of the party. Young, articulate, conservative and Hispanic, he was the ideal candidate. In April 2015, Rubio announced his campaign for the presidency. He was one of 17 Republican candidates and was consider one of the front-runners. Rubio turned out to be one of the great political underachievers in modern politics. He won only three of the 32 primaries and caucuses, winning Minnesota, Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia. Tea Party voters who carried him into the U.S. Senate in 2010 deserted him in the presidential campaign. “America is in the middle of a real political storm, a real tsunami, and we should have seen this coming,” Rubio said in his concession speech. Donald Trump destroyed Rubio in his home state where Rubio had never lost an election. Trump got 45.7 percent of the vote; Rubio got only 27 percent. Trump won 66 of Florida’s 67 counties. The only county Rubio won was his home county of Miami-Dade. All of Florida’s 99 delegates were awarded to Trump. Not only did Rubio get trounced, but Trump also laid to rest the myth that he could not win in a closed primary state. It was the Republican voters of Florida who said yes to Trump and no to Rubio. What went wrong for Rubio? Among the many explanations is Rubio’s role as a member of “the gang of 8” who pushed for immigration reform and a pathway for citizenship for illegal aliens. There is some truth to this, but among Florida’s primary voters, only 12 percent mentioned immigration as a major factor in their vote. Others cited Rubio’s devastating performance in the New Hampshire debate where Chris Christie accused Rubio of being a robotic, scripted candidate who merely repeated his 25-second talking points. Rubio repeated the same talking point three times during the debate. He finished in fifth place in New Hampshire. Rubio’s campaign was widely criticized for its reliance on a media-focused approach. As his campaign manager, Terry Sullivan, told the New York Times: “More people in Iowa see Marco on ‘Fox and Friends’ than see Marco when he is in Iowa.” However, numerous studies demonstrate that a solid ground game can produce a voter boost of up to 10 percent on Election Day and a good telephone effort can add another 4 percent. Finally, many believe Rubio delivered the wrong message at the wrong time. He alluded to this in his concession speech when he said, “this may not have been the year for a hopeful and optimistic message.” Republican voters wanted someone to channel their anger into reforming politics and solving problems. March 15 was the Ides of March. To paraphrase Marc Antony, “I come to bury Marco, not to praise him.” *** Darryl Paulson, Emeritus Professor of Government, USF St. Petersburg.

Not long ago, Marco Rubio questioned his own readiness for presidency

Marco Rubio lacks the experience to be president and Jeb Bush is a brilliant man ready for the job. So said Marco Rubio. Thing is, that was Rubio a few years ago, a man of seeming humility who joked that the only thing he deserved being president of was a condo association. He dismissed in colorful terms the idea that one term in the Senate could make a man ready for the White House. “Everyone I’ve ever known that tries to use their position as a stepping stone for something else has ended up destroying themselves,” he said during a 2012 book tour. Times — and ambition and ego — have changed. Bush, the former governor who guided Rubio’s early political career, won Rubio’s praise as “one of the biggest, best thinkers in the Republican Party” with an “amazing” depth of knowledge on almost every issue. Now Rubio says America doesn’t need politicians from the past. After shooing off the roars of supporters in his 2010 Senate campaign who saw presidential mettle in him — “it’s fleeting and it’s not going to get to my head” — it’s now firmly in his head. He’s hardly the first to be seized with the audacity of presidential hopes, even if others have taken a bit longer to get from you-must-be-kidding to yes-we-can. Barack Obama‘s star turn at the 2004 convention, just two years after being elected to the Senate from a background as a state lawmaker, made clear that the White House was in that young man’s eyes. Few, though, have put down their own bona fides as thoroughly as Rubio did in his rough-and-tumble Senate campaign, when he wanted voters to know that a Senate seat was his total dream and devotion. Then, he was stunned to be recognized at a Florida Panhandle truck stop while making a 400-mile round-trip drive so he could talk to 80 voters. The trip cost him as much as he raised in campaign contributions. Republican leaders in Tallahassee and Washington were trying to force him out of the race and have him run for attorney general so then-Republican Gov. Charlie Crist could have a clean shot at the nomination. “It was unpleasant,” Rubio said at the time, “but I’m glad it happened because it forced me to answer a very simple question to myself and that is, why are you doing this?” He decided “I’m in this because I want to do something.” Rubio began the Senate race 31 points down in polls. Crist was raising $13 for every $1 Rubio took in. But Rubio used Tea Party rallies, the image of Crist embracing Obama and a well-delivered conservative message to top Crist by 20 points and drive him from the party. Along the way he’d poke fun at Obama’s sudden rise to power — a way of playing down suggestions that he could do the same. Like Rubio, Obama announced his presidential plans during his first Senate term. He cracked at one Senate campaign stop that he was running because he wanted a Nobel Peace Prize, “but you’ve got to be in office two weeks to do that, so I’m going to have to wait.” Obama got the prize his first year in office, the Nobel committee citing his support for multilateral diplomacy and for a world without nuclear weapons. The night Rubio won his seat, supporters roared when a speaker asked them if they wanted to see Rubio run for president. The next day Rubio pushed aside that talk. “Politics is full of one-hit wonders,” Rubio told reporters. “The truth is soon you will all go off and cover something else and there will be somebody else out there who’s the flavor of the month, and then I’m still going to be a U.S. senator.” Two years later at a Panama City book signing, a man approached Rubio and said he should run for president in 2016. Rubio dismissed the idea afterward, and pointed to Bush instead. “It’s just amazing to me the depth of knowledge that he has on virtually any issue from foreign relations to the economy and obviously education,” he said. Yet right after the 2012 election, Rubio was the first of the 2016 prospects to visit Iowa. His conviction that he’s ready for the presidency did not develop overnight. Now, Rubio calls on voters to break with leaders of the last century. And his goals are much more ambitious than being a condo association president. Republished with permission of The Associated Press.