Court rejects GOP redistricting plans in North Carolina, Pennsylvania

In a victory for Democrats, the Supreme Court has turned away efforts from Republicans in North Carolina and Pennsylvania to block state court-ordered congressional districting plans. In separate orders late Monday, the justices are allowing maps selected by each state’s Supreme Court to be in effect for the 2022 elections. Those maps are more favorable to Democrats than the ones drawn by the states’ legislatures. In North Carolina, the map most likely will give Democrats an additional House seat in 2023. The Pennsylvania map also probably will lead to the election of more Democrats, the Republicans say, as the two parties battle for control of the U.S. House of Representatives in the midterm elections in November. The justices provided no explanation for their actions, as is common in emergency applications on what is known as the “shadow docket.” While the high court did not stop the state court-ordered plans from being used in this year’s elections, four conservative justices indicated they want it to confront the issue that could dramatically limit the power of state courts over federal elections in the future. The Republicans argued that state courts lack the authority to second-guess legislatures’ decisions about the conduct of elections for Congress and the presidency. “We will have to resolve this question sooner or later, and the sooner we do so, the better. This case presented a good opportunity to consider the issue, but unfortunately, the court has again found the occasion inopportune,” Justice Samuel Alito wrote in a dissent from the Supreme Court’s order, joined by Justices Neil Gorsuch and Clarence Thomas. Justice Brett Kavanaugh made a similar point but said he didn’t want to interfere in this year’s electoral process, which already is underway. The filing deadline in North Carolina was Friday. The state courts were involved because of partisan wrangling and lawsuits over congressional redistricting in both states, where the legislatures are controlled by Republicans, the governors are Democrats, and the state Supreme Courts have Democratic majorities. In Pennsylvania, Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf vetoed the plan the Republican-controlled Legislature approved, saying it was the result of a “partisan political process.” The state, with a delegation of nine Democrats and nine Republicans, is losing a seat in the House following the 2020 Census. Republicans said the map they came up with would elect nine Democrats and eight Republicans. State courts eventually stepped in and approved a map that probably will elect 10 Democrats, the GOP argued. North Carolina is picking up a seat in the House because of population gains. Republican majorities in the Legislature produced an initial plan most likely to result in 10 seats for Republicans and four for Democrats. The governor does not have veto power over redistricting plans in North Carolina. After Democrats sued, the state’s high court selected a map that likely will elect at least six Democrats. Lawsuits are continuing in both states, but the Supreme Court signaled in Monday’s orders that this year’s elections for Congress in North Carolina and Pennsylvania would take place under the maps approved by the states’ top courts. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

‘Obamacare’ survives: Supreme Court dismisses big challenge

The Supreme Court, though increasingly conservative in makeup, rejected the latest major Republican-led effort to kill the national health care law known as “Obamacare” on Thursday, preserving insurance coverage for millions of Americans. The justices, by a 7-2 vote, left the entire Affordable Care Act intact in ruling that Texas, other GOP-led states, and two individuals had no right to bring their lawsuit in federal court. The Biden administration says 31 million people have health insurance because of the law, which also survived two earlier challenges in the Supreme Court. The law’s major provisions include protections for people with existing health conditions, a range of no-cost preventive services, expansion of the Medicaid program that insures lower-income people, and access to health insurance markets offering subsidized plans. “The Affordable Care Act remains the law of the land,” President Joe Biden, said, celebrating the ruling. He called for building further on the law that was enacted in 2010 when he was vice president. Also left in place is the law’s now-toothless requirement that people have health insurance or pay a penalty. Congress rendered that provision irrelevant in 2017 when it reduced the penalty to zero. The elimination of the penalty had become the hook that Texas and other GOP-led states, as well as the Trump administration, used to attack the entire law. They argued that without the mandate, a pillar of the law when it was passed, the rest of the law should fall, too. And with a Supreme Court that includes three appointees of former President Donald Trump, opponents of “Obamacare” hoped a majority of the justices would finally kill the law they have been fighting for more than a decade. But the third major attack on the law at the Supreme Court ended the way the first two did, with a majority of the court rebuffing efforts to gut the law or get rid of it altogether. Trump’s appointees — Justices Amy Coney Barrett, Neil Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanaugh — split their votes. Kavanaugh and Barrett joined the majority. Gorsuch was in dissent, signing on to an opinion from Justice Samuel Alito. Justice Stephen Breyer wrote for the court that the states and people who filed a federal lawsuit “have failed to show that they have standing to attack as unconstitutional the Act’s minimum essential coverage provision.” In dissent, Alito wrote, “Today’s decision is the third installment in our epic Affordable Care Act trilogy, and it follows the same pattern as installments one and two. In all three episodes, with the Affordable Care Act facing a serious threat, the Court has pulled off an improbable rescue.” Alito was a dissenter in the two earlier cases in 2012 and 2015, as well. Like Alito, Justice Clarence Thomas was in dissent in the two earlier cases, but he joined Thursday’s majority, writing, “Although this Court has erred twice before in cases involving the Affordable Care Act, it does not err today.” Because it dismissed the case for the plaintiff’s lack of legal standing — the ability to sue — the court didn’t actually rule on whether the individual mandate is unconstitutional now that there is no penalty for forgoing insurance. Lower courts had struck down the mandate, in rulings that were wiped away by the Supreme Court decision. With the latest ruling, the Supreme Court reaffirmed that “the Affordable Care Act is here to stay,” former President Barack Obama said, adding his support to Biden’s call to expand the law. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton pledged to continue the fight against “Obamacare,” which he called a “massive government takeover of health care.” But it’s not clear what Republicans can do, said Larry Levitt, an executive vice president for the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation, which studies health care. “Democrats are in charge and they have made reinvigorating and building on the ACA a key priority,” Levitt said. “Republicans don’t seem to have much enthusiasm for continuing to try to overturn the law.” Republicans have pressed their argument to invalidate the whole law even though congressional efforts to rip out the entire law “root and branch,” in Senate GOP leader Mitch McConnell’s words, have failed. The closest they came was in July 2017 when Arizona Sen. John McCain, who died the following year, delivered a dramatic thumbs-down vote to a repeal effort by fellow Republicans. Chief Justice John Roberts said during arguments in November that it seemed the law’s foes were asking the court to do work best left to the political branches of government. The court’s decision preserves benefits that have become part of the fabric of the nation’s health care system. Polls show that the law has grown in popularity as it has endured the heaviest assault. In December 2016, just before Obama left office and Trump swept in calling the ACA a “disaster,” 46% of Americans had an unfavorable view of the law, while 43% approved, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation tracking poll. Those ratings flipped, and by February of this year, 54% had a favorable view, while disapproval had fallen to 39% in the same ongoing poll. The health law is now undergoing an expansion under Biden, who sees it as the foundation for moving the U.S. to coverage for all. His giant COVID-19 relief bill significantly increased subsidies for private health plans offered through the ACA’s insurance markets, while also dangling higher federal payments before the dozen states that have declined the law’s Medicaid expansion. About 1.2 million people have signed up with HealthCare.gov since Biden reopened enrollment amid high levels of COVID cases earlier this year. Most of the people with insurance because of the law have it through Medicaid expansion or the health insurance markets that offer subsidized private plans. But its most popular benefit is protection for people with preexisting medical conditions. They cannot be turned down for coverage on account of health problems or charged a higher premium. While those covered under employer plans already had such protections, “Obamacare” guaranteed them for people buying

Aron Solomon: The Supreme Court and the Donald Trump Twitter blocks

On Monday morning, in Biden v. Knight First Amendment Institute (the Trump Twitter blocks case), the Supreme Court vacated and remanded, with Justice Clarence Thomas concurring. Those following this issue closely will also remember that Alabama Secretary of State, John Merrill, was sued by the ACLU over similar twitter blocking. This week’s decision is just as relevant to state issues as it is to national ones. There is plenty of interest in Thomas’s concurring opinion to the order directing the Second Circuit to dismiss the Trump Twitter blocks case as moot. Justice Thomas wrote that it may be time to treat social media platforms as common carriers. “…our legal system and its British predecessor have long subjected certain businesses, known as common carriers, to special regulations, including a requirement to serve all comers.” This case has been under the social spotlight from the time of its filing. The facts of the case are fairly simple and linear. Seven private Twitter users were blocked after they criticized then-President Donald Trump on the platform. For the uninitiated, this means that when those users went on to the Twitter online platform, they could not social media see the President’s tweets (if they were logged into Twitter), and under no circumstances could they reply to retweet President Trump. So those seven Twitter users sued, joined by the Knight First Amendment Institute, which is part of Columbia University in New York. Private citizen Donald J. Trump set up his Twitter account in March 2009 and brought it with him to the White House, where it became his most infamous way to send messages to his constituents and the world. Unlike any other President in American history, President Trump regularly used the Twitter platform to make policy, discipline personnel, share his opinion on political and entirely non-political issues, and, once he lost the 2020 election, communicate often popular, yet entirely unfounded claims of election fraud. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that a Twitter or other social media account run by government officials can become a constitutionally protected “public forum” if used to conduct official business. The Supreme Court had earlier ruled that the views of any speaker may not be discriminated against in a public forum, whether in person or online. Before President Trump was voted out of office, the parties continued to battle over the Second Circuit’s decision. Lawyers representing the United States Department of Justice claimed that the Second Circuit’s decision means that high government officials could easily have their social media pages destroyed by hate speech and other forms of online harassment. Of course, when President Trump left office in January, the case lost all of its practical impact, the final nail in this online coffin being Twitter’s decision in early January to permanently ban former President Trump for glorifying violence. Anthony J. Vecchio, a New Jersey-based lawyer, observed that the concurring opinion of Justice Thomas may prove even more important than we imagine today. “If it becomes the stated position of the Supreme Court that Internet messaging platforms such as Twitter should be treated like phone companies or similar utilities, where does this actually stop? This week’s concurring opinion may very well be opening a door few realistically expected to have opened.” There is an argument to be made here that the 6-3 majority conservative Supreme Court should express more directly what it really means: That they want to support conditions in which the federal government (and, practically, GOP politicos) is able to force private companies such as Twitter to communicate their public messages. Historians may argue that Justice Thomas is misapplying the law of common carries and the relevant laws that govern public accommodations. Common carriers are duty-bound to serve travelers who are especially vulnerable precisely because they are away from home. Applying this so Silicon Valley social media behemoths may be a stretch. Skeptics may also say that this is Justice Thomas signaling to lawyers what kind of lawsuits to file. It also might be a sign of inconsistency, given the majority opinion he joined in Boy Scouts of America v. Dale? Again, there might be a rational argument that the only difference between the cases is that Twitter has far more members than the Boy Scouts. Aron Solomon is the Head of Digital Strategy for NextLevel.com and an adjunct professor of business management at the Desautels Faculty of Management at McGill University.

Religion and the death penalty collide at the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court is sending a message to states that want to continue to carry out the death penalty: Inmates must be allowed to have a spiritual adviser by their side as they are executed. The high court around midnight Thursday declined to let Alabama proceed with the lethal injection of Willie B. Smith III. Smith had objected to Alabama’s policy that his pastor would have had to observe his execution from an adjacent room rather than the death chamber itself. The order from the high court follows two years in which inmates saw some rare success in bringing challenges based on the issue of chaplains in the death chamber. This time, liberal and conservative members of the court normally in disagreement over death penalty issues found common ground not on the death penalty itself but on the issue of religious freedom and how the death penalty is carried out. Justice Brett Kavanaugh, one of three justices who said they would have let Smith’s execution go forward, said Alabama’s policy applies equally to all inmates and serves a state interest in ensuring safety and security. But he said it was apparent that his colleagues who disagreed were providing a path for states to follow. States that want to avoid months or years of litigation over the presence of spiritual advisers “should figure out a way to allow spiritual advisors into the execution room, as other States and the Federal Government have done,” he wrote in a dissent joined by Chief Justice John Roberts. Justice Clarence Thomas also would have allowed the execution of Smith, who was sentenced to die for the 1991 murder of 22-year-old Sharma Ruth Johnson in Birmingham. Alabama had up until 2019 allowed a Christian prison chaplain employed by the state to be physically present in the execution chamber if requested by the inmate, but the state changed its policy in response to two earlier Supreme Court cases. Robert Dunham, the executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, says the court’s order will most clearly affect states in the Deep South that have active execution chambers. Dunham said most state execution protocols, which set who is present in the death chamber, do not mention spiritual advisers. For most of the modern history of the U.S. death penalty since the 1970s, spiritual advisers have not been present in execution chambers, he said. The federal government, which under President Donald Trump resumed federal executions following a 17-year hiatus and carried out 13 executions, allowed a spiritual adviser to be present in the death chamber. The Biden administration is still weighing how it will proceed in death penalty cases. The court’s order in Smith’s case contained only statements from Kavanaugh and Justice Elena Kagan. “Willie Smith is sentenced to death, and his last wish is to have his pastor with him as he dies,” Kagan wrote for herself and liberal justices Sonia Sotomayor and Stephen Breyer, as well as conservative Amy Coney Barrett. Kagan added: “Alabama has not carried its burden of showing that the exclusion of all clergy members from the execution chamber is necessary to ensure prison security.” Justice Neil Gorsuch and Justice Samuel Alito did not make public their views, but at least one or perhaps both of them must have voted with their liberal colleagues to keep Smith’s execution on hold. The court’s yearslong wrestling with the issue of chaplains in the death chamber began in 2019, when the justices declined to halt the execution of Alabama inmate Domineque Ray. Ray had objected that a Christian chaplain employed by the prison typically remained in the execution chamber during a lethal injection, but the state would not let his imam be present. The next month, however, the justices halted the execution of a Texas inmate, Patrick Murphy, who objected after Texas officials wouldn’t allow his Buddhist spiritual adviser in the death chamber. Kavanaugh wrote at the time that states have two choices: Allow all inmates to have a religious adviser of their choice in the execution room or allow that person only in an adjacent viewing room. In response, the Texas prison system changed its policy, allowing only prison security staff into the execution chamber. But in June, the high court kept Texas from executing Ruben Gutierrez after he objected to the new policy. Diana Verm, a lawyer at the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, which had submitted briefs in two of the spiritual adviser cases, said it was unusual for the court with its conservative majority to halt executions. “You can tell from some of the opinions that the justices don’t like the last-minute nature of execution litigation, but this is an area where they are saying: ’Listen … religious liberty has to be a part of the process if it’s going to happen,” Verm said. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

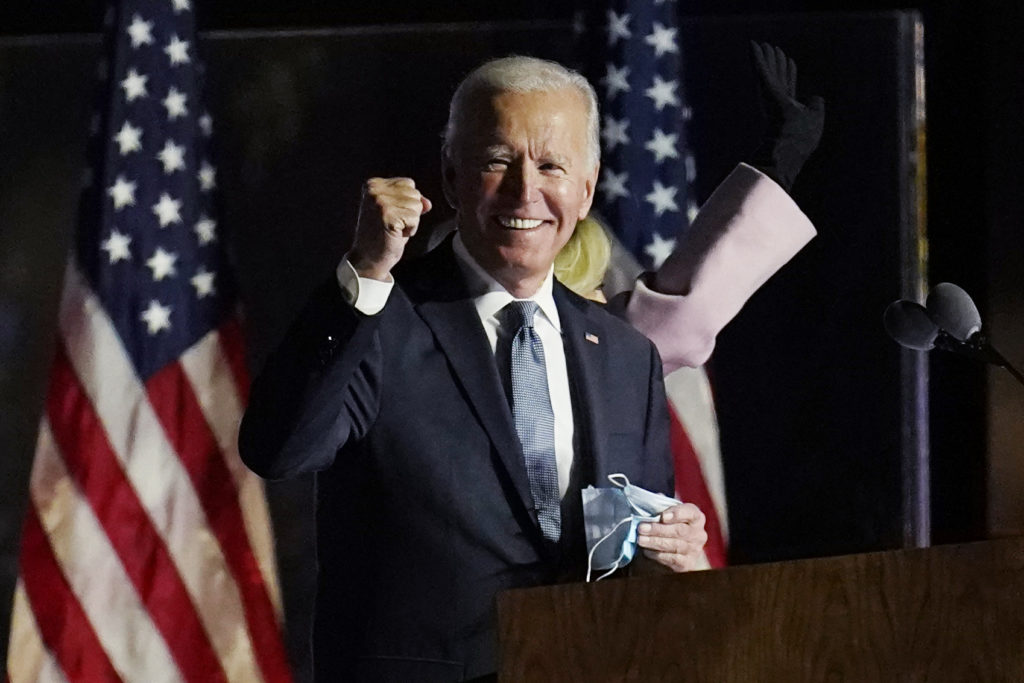

Joe Biden wins White House, vowing new direction for divided U.S.

Democrat Joe Biden defeated President Donald Trump to become the 46th president of the United States on Saturday, positioning himself to lead a nation gripped by a historic pandemic and a confluence of economic and social turmoil. His victory came after more than three days of uncertainty as election officials sorted through a surge of mail-in votes that delayed the processing of some ballots. Biden crossed 270 Electoral College votes with a win in Pennsylvania. Biden, 77, staked his candidacy less on any distinctive political ideology than on galvanizing a broad coalition of voters around the notion that Trump posed an existential threat to American democracy. The strategy proved effective, resulting in pivotal victories in Michigan and Wisconsin as well as Pennsylvania, onetime Democratic bastions that had flipped to Trump in 2016. Biden was on track to win the national popular vote by more than 4 million, a margin that could grow as ballots continue to be counted. Trump seized on delays in processing the vote in some states to falsely allege voter fraud and argue that his rival was trying to seize power — an extraordinary charge by a sitting president trying to sow doubt about a bedrock democratic process. As the vote count played out, Biden tried to ease tensions and project an image of presidential leadership, hitting notes of unity that were seemingly aimed at cooling the temperature of a heated, divided nation. “We have to remember the purpose of our politics isn’t total unrelenting, unending warfare,” Biden said Friday night in Delaware. “No, the purpose of our politics, the work of our nation, isn’t to fan the flames of conflict, but to solve problems, to guarantee justice, to give everybody a fair shot.” Kamala Harris also made history as the first Black woman to become vice president, an achievement that comes as the U.S. faces a reckoning on racial justice. The California senator, who is also the first person of South Asian descent elected to the vice presidency, will become the highest-ranking woman ever to serve in government, four years after Trump defeated Hillary Clinton. Trump is the first incumbent president to lose reelection since Republican George H.W. Bush in 1992. It was unclear whether Trump would publicly concede. Americans showed deep interest in the presidential race. A record 103 million voted early this year, opting to avoid waiting in long lines at polling locations during a pandemic. With counting continuing in some states, Biden had already received more than 74 million votes, more than any presidential candidate before him. More than 236,000 Americans have died during the coronavirus pandemic, nearly 10 million have been infected and millions of jobs have been lost. The final days of the campaign played out against the backdrop of a surge in confirmed cases in nearly every state, including battlegrounds such as Wisconsin that swung to Biden. The pandemic will soon be Biden’s to tame, and he campaigned pledging a big government response, akin to what Franklin D. Roosevelt oversaw with the New Deal during the Depression of the 1930s. But Senate Republicans fought back several Democratic challengers and looked to retain a fragile majority that could serve as a check on such Biden ambition. The 2020 campaign was a referendum on Trump’s handling of the pandemic, which has shuttered schools across the nation, disrupted businesses and raised questions about the feasibility of family gatherings heading into the holidays. The fast spread of the coronavirus transformed political rallies from standard campaign fare to gatherings that were potential public health emergencies. It also contributed to an unprecedented shift to voting early and by mail and prompted Biden to dramatically scale back his travel and events to comply with restrictions. Trump defied calls for caution and ultimately contracted the disease himself. He was saddled throughout the year by negative assessments from the public of his handling of the pandemic. Biden also drew a sharp contrast to Trump through a summer of unrest over the police killings of Black Americans including Breonna Taylor in Kentucky and George Floyd in Minneapolis. Their deaths sparked the largest racial protest movement since the civil rights era. Biden responded by acknowledging the racism that pervades American life, while Trump emphasized his support of police and pivoted to a “law and order” message that resonated with his largely white base. The president’s most ardent backers never wavered and may remain loyal to him and his supporters in Congress after Trump has departed the White House. The third president to be impeached, though acquitted in the Senate, Trump will leave office having left an indelible imprint in a tenure defined by the shattering of White House norms and a day-to-day whirlwind of turnover, partisan divide and the ever-present threat via his Twitter account. Biden, born in Scranton, Pennsylvania, and raised in Delaware, was one of the youngest candidates ever elected to the Senate. Before he took office, his wife and daughter were killed, and his two sons badly injured in a 1972 car crash. Commuting every night on a train from Washington back to Wilmington, Biden fashioned an everyman political persona to go along with powerful Senate positions, including chairman of the Senate Judiciary and Foreign Relations Committees. Some aspects of his record drew critical scrutiny from fellow Democrats, including his support for the 1994 crime bill, his vote for the 2003 Iraq War and his management of the Clarence Thomas’ Supreme Court hearings. Biden’s 1988 presidential campaign was done in by plagiarism allegations, and his next bid in 2008 ended quietly. But later that year, he was tapped to be Barack Obama’s running mate and he became an influential vice president, steering the administration’s outreach to both Capitol Hill and Iraq. While his reputation was burnished by his time in office and his deep friendship with Obama, Biden stood aside for Clinton and opted not to run in 2016 after his adult son Beau died of brain cancer the year before. Trump’s tenure pushed Biden to make

Amy Coney Barrett confirmed as Supreme Court justice

Amy Coney Barrett was confirmed to the Supreme Court late Monday by a deeply divided Senate, Republicans overpowering Democrats to install President Donald Trump’s nominee days before the election and secure a likely conservative court majority for years to come. Trump’s choice to fill the vacancy of the late liberal icon Ruth Bader Ginsburg potentially opens a new era of rulings on abortion, the Affordable Care Act and even his own election. Democrats were unable to stop the outcome, Trump’s third justice on the court, as Republicans race to reshape the judiciary. Barrett is 48, and her lifetime appointment as the 115th justice will solidify the court’s rightward tilt. Monday’s vote was the closest high court confirmation ever to a presidential election, and the first in modern times with no support from the minority party. The spiking COVID-19 crisis has hung over the proceedings. Vice President Mike Pence’s office said Monday he would not preside at the Senate session unless his tie-breaking vote was needed after Democrats asked him to stay away when his aides tested positive for COVID-19. The vote was 52-48, and Pence’s vote was not necessary. With Barrett’s confirmation assured, Trump was expected to celebrate with a primetime swearing-in event at the White House. Justice Clarence Thomas was set to administer the Constitutional Oath, a senior White House official said. “Voting to confirm this nominee should make every single senator proud,” said Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, fending off “outlandish” criticism in a lengthy speech. During a rare weekend session he declared that Barrett’s opponents “won’t be able to do much about this for a long time to come.” Pence’s presence presiding for the vote would have been expected, showcasing the Republican priority. But Senate Democratic leader Chuck Schumer and his leadership team said it would not only violate virus guidelines of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “it would also be a violation of common decency and courtesy.” Some GOP senators tested positive for the coronavirus following a Rose Garden event with Trump to announce Barrett’s nomination last month, but they have since said they have been cleared by their doctors from quarantine. Pence was not infected and his office said the vice president tested negative for the virus Monday. Underscoring the political divide during the pandemic, the Republican senators, most wearing masks, sat in their seats, as is tradition for landmark votes, and applauded the outcome. Democratic senators were not present, heeding Schumer’s advice not to linger in the chamber. Democrats argued for weeks that the vote was being improperly rushed and insisted during an all-night Sunday session it should be up to the winner of the Nov. 3 election to name the nominee. However, Barrett, a federal appeals court judge from Indiana, is expected to be seated swiftly, and begin hearing cases. Speaking near midnight Sunday, Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., called the vote “illegitimate” and “the last gasp of a desperate party.” Several matters are awaiting decision just a week before Election Day, and Barrett could be a decisive vote in Republican appeals of orders extending the deadlines for absentee ballots in North Carolina and Pennsylvania. The justices also are weighing Trump’s emergency plea for the court to prevent the Manhattan District Attorney from acquiring his tax returns. And on Nov. 10, the court is expected to hear the Trump-backed challenge to the Obama-era Affordable Care Act. Just before the Senate vote began, the court sided with Republicans in refusing to extend the deadline for absentee ballots in Wisconsin. Trump has said he wanted to swiftly install a ninth justice to resolve election disputes and is hopeful the justices will end the health law known as “Obamacare.” During several days of public testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Barrett was careful not to disclose how she would rule on any such cases. She presented herself as a neutral arbiter and suggested, “It’s not the law of Amy.” But her writings against abortion and a ruling on “Obamacare” show a deeply conservative thinker. Full Coverage: U.S. Supreme Court Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., the chairman of the Judiciary Committee, praised the mother of seven as a role model for conservative women. “This is historic,” Graham said. Republicans focused on her Catholic faith, criticizing earlier Democratic questions about her beliefs. Graham called Barrett “unabashedly pro-life.” At the start of Trump’s presidency, McConnell engineered a Senate rules change to allow confirmation by a majority of the 100 senators, rather than the 60-vote threshold traditionally needed to advance high court nominees over objections. That was an escalation of a rules change Democrats put in place to advance other court and administrative nominees under President Barack Obama. Republicans are taking a political plunge by pushing for confirmation days from the Nov. 3 election with the presidency and their Senate majority at stake. Only one Republican — Sen. Susan Collins, who is in a tight reelection fight in Maine — voted against the nominee, not over any direct assessment of Barrett. Rather, Collins said, “I do not think it is fair nor consistent to have a Senate confirmation vote prior to the election.” Trump and his Republican allies had hoped for a campaign boost, in much the way Trump generated excitement among conservatives and evangelical Christians in 2016 over a court vacancy. That year, McConnell refused to allow the Senate to consider then-President Barack Obama’s choice to replace the late Justice Antonin Scalia, arguing the new president should decide. Most other Republicans facing tough races embraced the nominee who clerked for the late Scalia to bolster their standing with conservatives. Sen. Thom Tillis, R-N.C., said in a speech Monday that Barrett will “go down in history as one of the great justices.” But it’s not clear the extraordinary effort to install the new justice over such opposition in a heated election year will pay political rewards to the GOP. Demonstrations for and against the nominee have been more muted at the Capitol under coronavirus restrictions. Democrats were unified against Barrett. While two Democratic senators voted to confirm

Donald Trump picks conservative Amy Coney Barrett for Supreme Court

President Donald Trump nominated Judge Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court on Saturday, capping a dramatic reshaping of the federal judiciary that will resonate for a generation and that he hopes will provide a needed boost to his reelection effort. Republican senators are already lining up for a swift confirmation of Barrett ahead of the Nov. 3 election, as they aim to lock in conservative gains in the federal judiciary before a potential transition of power. Trump, meanwhile, is hoping the nomination will serve to galvanize his supporters as he looks to fend off Democrat Joe Biden. Trump hailed Barrett as “a woman of remarkable intellect and character,” saying he had studied her record closely before making the pick. “I looked and I studied, and you are very eminently qualified,” he said as Barrett stood next to him in the Rose Garden. An ideological heir to the late conservative Justice Antonin Scalia, Barrett would fill the seat vacated after the Sept. 18 death of liberal icon Ruth Bader Ginsberg, in what would be the sharpest ideological swing since Clarence Thomas replaced Justice Thurgood Marshall nearly three decades ago. She would be the sixth justice on the nine-member court to be appointed by a Republican president, and the third of Trump’s first term in office. For Trump, whose 2016 victory hinged in large part on reluctant support from conservative and white evangelicals on the promise of filling Scalia’s seat with a conservative, the latest nomination in some ways brings his first term full circle. Even before Ginsburg’s death, Trump was running on having confirmed in excess of 200 federal judges, fulfilling a generational aim of conservative legal activists. “This is my third such nomination after Justice Neil Gorsuch and Justice Brett Kavanaugh, and it is a very proud moment indeed,” Trump said in the Rose Garden. Trump joked that the confirmation process ahead “should be easy” and “extremely non-controversial,” though it is likely to be anything. No court nominee has been considered so close to a presidential election before, with early voting already underway. He encouraged Democrats to take up her nomination swiftly and to “refrain from personal and partisan attacks.” In 2016, Republicans blocked President Barack Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland to the Supreme Court to fill the election-year vacancy, saying voters should have a say in the lifetime appointment. Senate Republicans say they will move ahead, arguing the circumstances are different now that the White House and Senate are controlled by the same party. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said the Senate will vote “in the weeks ahead” on Barrett’s confirmation, adding that Trump “could not have made a better decision” in nominating the appellate court judge. The announcement came before Ginsburg was buried beside her husband next week at Arlington National Cemetery. On Friday, she was the first woman to lie in state at the Capitol, and mourners flocked to the Supreme Court for two days before that to pay respects. The set design, with large American flags hung between the Rose Garden colonnades, appeared to be modeled on the way the White House was decorated when President Bill Clinton named Ginsburg as his nominee in 1993. Barrett said she was “truly humbled” by the nomination, adding that she would be “mindful of who came before me.” She praised Ginsburg upon accepting the nomination, saying, “She has won the admiration of women across the country and indeed all across the world.” Within hours of Ginsburg’s death, Trump made clear he would nominate a woman for the seat, and later volunteered he was considering five candidates. But Barrett was the early favorite, and the only one to meet with Trump. Barrett has been a judge since 2017 when Trump nominated her to the Chicago-based 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. But as a longtime University of Notre Dame law professor, she had already established herself as a reliable conservative in the mold of Scalia, for whom she clerked in the late 1990s. She would be the only justice on the current court not to have received her law degree from an Ivy League school. The eight current justices all attended either Harvard or Yale. The staunch conservative had become known to Trump in large part after her bitter 2017 appeals court confirmation included allegations that Democrats were attacking her Catholic faith. The president also interviewed her in 2018 for the vacancy created by the retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy, but Trump ultimately chose Brett Kavanaugh. Trump and his political allies are itching for another fight over Barrett’s faith, seeing it as a political windfall that would backfire on Democrats. Catholic voters in Pennsylvania, in particular, are viewed as a pivotal demographic in the swing state that Biden, also Catholic, is trying to recapture. While Democrats appear powerless to stop Barrett’s confirmation in the GOP-controlled Senate, they are seeking to use the process to weaken Trump’s reelection chances. Barrett’s nomination could become a reckoning over abortion, an issue that has divided many Americans so bitterly for almost half a century. The idea of overturning or gutting Roe v. Wade, the landmark 1973 decision that legalized abortion, has animated activists in both parties for decades. Now, with the seemingly decisive shift in the court’s ideological makeup, Democrats hope their voters will turn out in droves because of their frustration with the Barrett pick. Trump has also increasingly embraced the high court — which he will have had an outsize hand in reshaping -– as an insurance policy in a close election. Increases in mail, absentee, and early voting brought about by the coronavirus pandemic have already led to a flurry of election litigation, and both Trump and Biden have assembled armies of lawyers to continue the fight once vote-counting begins. Trump has been open about tying his push to name a third justice to the court to a potentially drawn-out court fight to determine who will be sworn in on Jan. 20, 2021. “I think this

Donald Trump interviews Amy Barrett while weighing a high court nominee

Trump said Monday he expects to announce his choice by week’s end, before the burial next week of Ginsburg.

Bernie Sanders refocusing his campaign after Joe Biden’s super Tuesday

Bernie Sanders declared himself “neck and neck” with Joe Biden as he faced reporters in his home state of Vermont.

Supreme Court Justices return for season of big decisions, amid campaign

There is a bumper crop of hot issues on the court’s agenda.

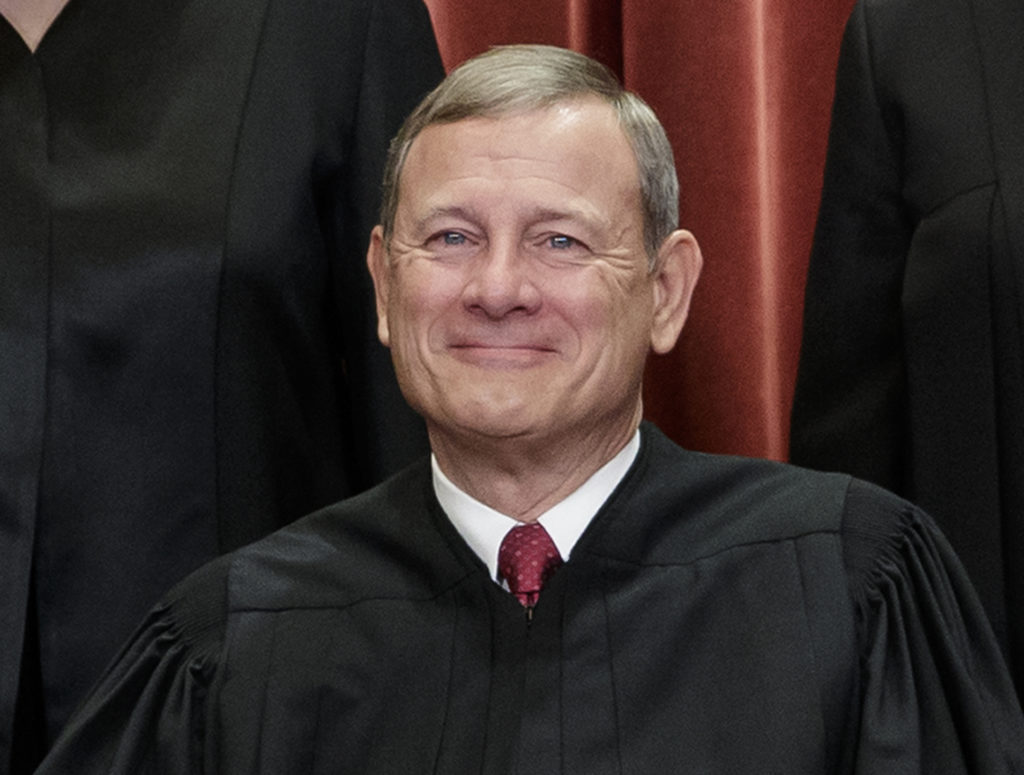

John Roberts’ Supreme Court defies easy political labels

Just hours after Chief Justice John Roberts handed Republicans a huge victory that protects even the most extreme partisan electoral districts from federal court challenge, critics blasted him as worthy of being impeached, a politician who should run for office and a traitor. But the attacks came from President Donald Trump’s allies and their anger was directed not at the Supreme Court’s partisan gerrymandering ruling, but at the day’s other big decision to keep a citizenship question off the 2020 census, at least for now. Trump tweeted from Japan that the census citizenship decision was “ridiculous.” What good is a high court conservative majority fortified by two Trump appointees, the critics seemed to be saying, if Roberts is not prepared to use it? That’s not how Roberts would characterize the court he now leads in name and as the justice closest to the center of a group otherwise divided between conservatives and liberals. He has talked repeatedly about the need to counter perceptions that the justices are just politicians in black robes, beholden to the president who appointed them. The flurry of action came at the end of a Supreme Court term in which the court welcomed a new justice, Brett Kavanaugh, who narrowly survived the most tumultuous confirmation hearings in nearly 30 years. The justices now begin a three-month summer recess. The court seem determined to maintain as low a profile as possible once Kavanaugh joined the bench in early October, finding a variety of ways to keep hot-button topics like abortion, guns, immigration and gay rights, that might divide conservatives from liberals, off the term’s calendar. “This tactic may have been an effort to keep things relatively quiet” following the Kavanaugh nomination, said Josh Blackman, a law professor at the South Texas College of Law in Houston. But one result of putting off some major decisions in Kavanaugh’s first term is a docket crammed with guns, immigration, gay rights and probably abortion in a session that begins in the fall and will come to a head in June 2020, amid the presidential election campaign. So far there is only a partial answer to the big question of how far and fast the court will move to the right now that the more conservative Roberts had taken the place of Justice Anthony Kennedy, who retired last year, as the swing justice. In the case of partisan gerrymandering, Roberts closed the federal courthouse door to lawsuits, a decision that mainly benefits Republicans whose districting plans had been challenged in several states. On the death penalty, the five conservatives appear much less willing to entertain calls for last-minute reprieves from execution. And in two cases the court divided along ideological lines in overturning precedents that had been on the books for more than 30 years. But Roberts was unwilling to join the conservatives to allow the citizenship question to proceed, although it is not yet clear whether the administration will continue pressing the legal case for the question. The reaction to the census ruling was swift. Former Trump aide Sebastian Gorka called Roberts “a traitor to Constitution.” American Conservative Union president Matt Schlapp called for Roberts’ impeachment. Fox News host Laura Ingraham tweeted that “Roberts should quit and run for office.” The chief justice also declined to be the fifth conservative vote to overturn two past high court decisions about the power of federal agencies, and joined the liberals in ruling for an Alabama death row inmate who suffers from dementia. In emergency appeals, Roberts was the fifth vote to keep Trump from requiring asylum seekers to enter the country at established checkpoints and the fifth vote to prevent Louisiana abortion clinic regulations from taking effect. Twenty-one decisions, or nearly a third of all the cases the court heard since October, were by 5-4 or 5-3 votes. But of those, only seven united the conservatives against dissenting liberals. In 10 others, the cohesive bloc of liberals attracted the vote of a conservative justice. The lack of high-profile cases undoubtedly contributed to the relatively small number of ideologically divided outcomes, said David Cole, legal director for the American Civil Liberties Union, which was on the winning side of the citizenship case and the losing side of the gerrymandering one.Cole said the 5-4 decisions that cross ideological lines “send a message that this is a court that is not just determined by partisan ideology, but is applying law.” Roberts sought to reinforce that perception of the court in comments in November, speaking out after Trump called a judge who ruled against his asylum policy an “Obama judge.” Roberts responded: “We do not have Obama judges or Trump judges, Bush judges or Clinton judges.” Commenting on the day before Thanksgiving, he said an “independent judiciary is something we should all be thankful for.” It could be several years before the impact of a more conservative court, assuming no changes in membership, becomes clear. But one fear among the liberal justices, and liberals more generally, is a push to restrict if not overturn abortion rights the Supreme Court first declared in the Roe v. Wade decision in 1973. At least one conservative justice has the decision in his sights. Justice Clarence Thomas at one point this term labeled it as “notoriously incorrect.” The first term of any new justice often has fewer big cases than normal, but the court’s desire to stay away from controversy was heightened by Kavanaugh’s difficult confirmation following allegations he sexually assaulted a woman when they were both in high school. He denied doing anything improper. When he arrived at the court, his colleagues seemed to welcome him warmly. Justice Elena Kagan, his neighbor on the bench, joked with the new justice and made a point of shaking his hand at the end of his first day of arguments. Kavanaugh’s parents were often in the courtroom, especially when their only child announced an opinion. The new justice “stuck pretty close to the chief in a lot of cases,” said Supreme

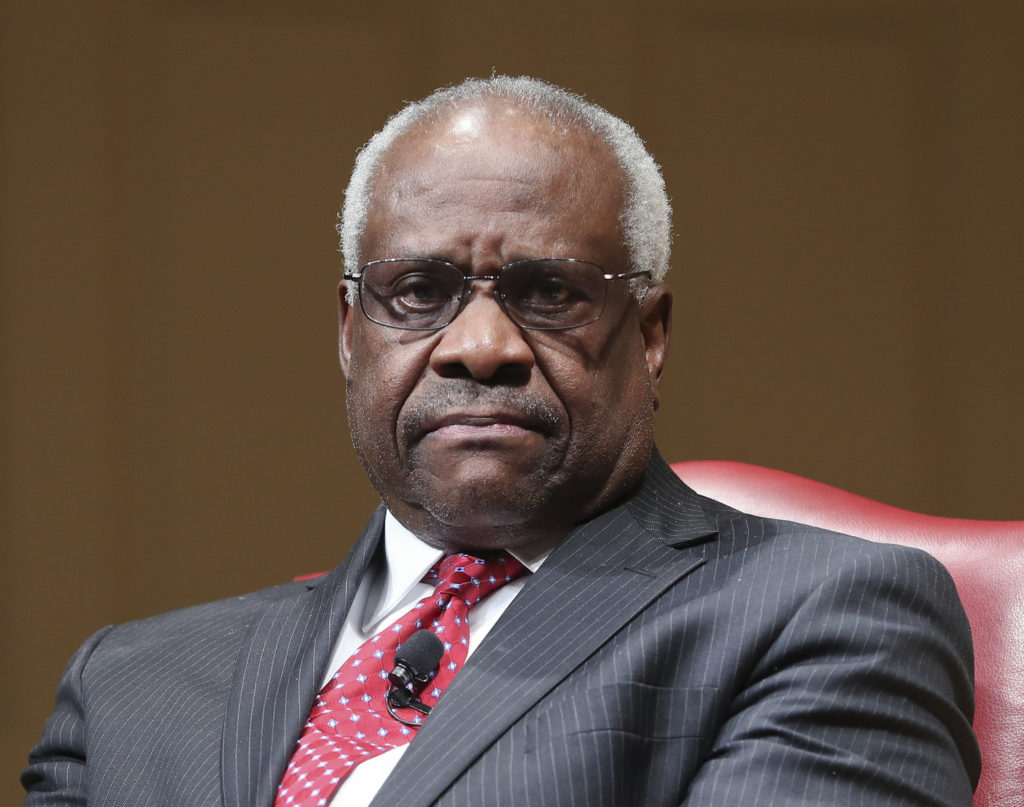

For Brett Kavanaugh, path forward could be like Clarence Thomas’

When Clarence Thomas arrived at the Supreme Court in 1991 after a bruising confirmation hearing in which his former employee Anita Hill accused him of sexual harassment, fellow justice Byron White said something that stuck with him. “It doesn’t matter how you got here. All that matters now is what you do here,” Thomas recounted in his 2007 memoir, “My Grandfather’s Son.” That view could be tested again if lawmakers confirm Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh, who’s facing allegations by California college professor Christine Blasey Ford that he sexually assaulted her when they were in high school. Kavanaugh, who like Thomas has denied the allegation against him, is scheduled to appear before lawmakers at a hearing Monday, with the outcome of his nomination uncertain. If Kavanaugh does become a justice, court watchers will be looking to see whether his smooth-turned-tumultuous confirmation affects him on the bench and whether having two justices who faced allegations about their treatment of women alters the public’s perception of the court, particularly on future rulings about abortion and gender discrimination. Thomas’ high-profile public showdown with Hill came to define his confirmation process, which he has called a “nightmare” and which Hill has called a “bane which I have worked hard to transform into a blessing.” Those who have studied or know Thomas say his confirmation didn’t change the kind of justice he has become. He is now 70 and the most conservative member of the court. But some observers suggest that — rightly or wrongly — it affected his public and private reception, particularly in his early years as a justice. Ralph A. Rossum, professor of government at Claremont McKenna College and the author of a 2013 book about Thomas’ legal philosophy, said Thomas’ “long and withering” confirmation didn’t make him any less willing to write unpopular opinions or interpret the Constitution as he sees it. “What it didn’t do is influence him on the bench,” said Rossum, who pointed to a dissent Thomas wrote shortly after joining the court, a case where only he and Justice Antonin Scalia would have ruled against an inmate beaten in prison. But Rossum said Thomas’ confirmation experience did seemingly make him “more gun-shy to be in public.” “I think he was always a private man, and it made him even more of a private man,” Rossum said. Law schools, generally only too happy to have justices speak at their events, also seemed to shun Thomas initially, Rossum said. It took a year and a half after he joined the court for him to give his first public speech. Since then, he has sometimes drawn protests when he makes appearances, but those are largely prompted by his conservative judicial philosophy. Hill’s allegations do resurface periodically, such as in 2010, when Thomas’ wife put them back in the news by leaving a telephone message for Hill suggesting she consider apologizing. Or, in the last year, as stories about the #MeToo movement have referenced Thomas. Former Missouri Sen. John Danforth, a longtime friend of Thomas’ who guided his confirmation, wrote in a 1994 book about the confirmation process that Thomas “has thought of the charge of sexual harassment as ‘a stain that won’t come off.’” But Thomas wasn’t changed by “the ordeal” he went through, Danforth said in a telephone interview. “He’s just the same, and he’s really a happy person, too,” he said. Danforth said Thomas “rose from the dead” after being confirmed. At a swearing-in ceremony at the White House ahead of joining the court, Thomas talked about moving on. “Today, now, it is a time to move forward, a time to look for what is good in others, what is good in our country,” he said. But not everyone believes that Thomas was able to move on so quickly. The hearings made him a recognizable face where before, as a judge, he enjoyed walking anonymously to lunch with his clerks, legal analyst Jeffrey Toobin wrote in his book “The Nine.” After his confirmation, Thomas stopped driving his black Corvette to work because the car was too recognizable, Toobin has written. And for years, Thomas purportedly kept in his desk a list of the roll-call vote on his confirmation. As for Thomas’ colleagues, they were cordial but not overly welcoming, Toobin wrote. Thomas, for his part, has denied that his reception was anything less than friendly, writing that all his colleagues treated him with the “utmost kindness and consideration.” But the confirmation process tainted how he felt about becoming a justice at the time. Thomas declined an invitation from the White House to watch as senators voted on his confirmation, and he was taking a hot bath when his wife told him he’d been confirmed 52-48. His response, according to his memoir: “Whoop-dee damn-doo.” Republished with permission from the Associated Press.