Democrats face identity crisis in next phase of 2020 race

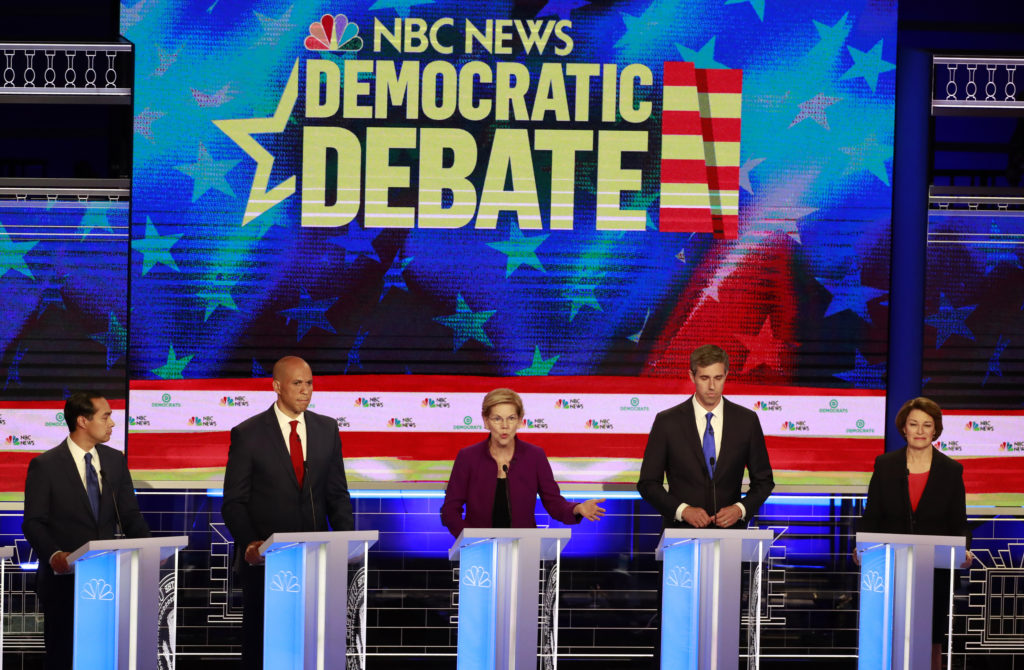

Doug Ogden doesn’t know what to do. The 75-year-old retired law enforcement officer is disgusted by President Donald Trump. But he can’t imagine voting for a Democrat in 2020, either. A self-described independent in South Carolina, Ogden doesn’t recognize the modern-day Democratic Party. “The state of the Democratic Party is wild against wilder,” says Ogden, standing with his arms crossed at a recent town hall meeting for Democratic presidential hopeful Pete Buttigieg. “It scares me.” At the core of Ogden’s concern is a broader question about the direction of the Democratic Party and its values in the age of Trump. While Democrats are united in their fierce opposition to the Republican president, most party leaders agree that Democrats will not reclaim the White House simply by running against him; they must give people something to vote for. But nine months into the first year of the 2020 campaign season, Democrats are no closer to resolving the big questions dividing their party by race, generation and ideology than they were on the day of Trump’s inauguration. And as the campaign enters a new heightened phase after Labor Day when far more voters begin paying closer attention, there is increasing pressure on Democrats to answer the questions behind their extended identity crisis. How can they peel back Trump’s support with white working class voters while boosting turnout with minorities and suburban women? How hard should they lean into anti-Trump fervor and calls for impeachment? And perhaps above of all, should they embrace transformational change on issues like health care, free college and higher taxes on the rich or a modest shift back to normalcy after Trump’s turbulent presidency? Some Democrats suggest an all-of-the-above strategy. But other presidential candidates, party leaders and top activists are searching for more definite answers to win over those anxious voters desperate for something or someone else to believe in. “There are diverse messages coming from diverse candidates,” Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont, a 2020 presidential candidate, said in an interview. “What the corporate media and the corporate pundits are trying to tell us is that it’s a middle-of-the-road agenda that will win the election. I categorically disagree,” said Sanders, a self-described democratic socialist. Sanders, of course, represents the Democratic Party’s energized left flank. Montana Gov. Steve Bullock, the only member of the Democrats’ 2020 class who has held statewide office in a state Trump won, fears his party will scare away the very same working class voters it needs to beat Trump if they embrace extreme change. “We need to make sure voters know we can improve upon their lives,” Bullock said in an interview. “That’s less about a revolution than addressing the problems of here and now.”In the middle of the Democratic Party’s quest for a clear identity are candidates like Kamala Harris and Buttigieg, the 37-year-old openly gay mayor of South Bend, Indiana, whose positions straddle the divide in a party whose poles are set by Sanders and Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts on the left and by former Vice President Joe Biden and Bullock, among others, as moderates. As Buttigieg courted overwhelmingly white audiences recently in rural South Carolina, he said it was a “false choice” to think Democrats have to appeal to minority voters at the expense of the white working class. And he offered a direct message to older, white voters like Ogden, who fear that his party has become too focused on the concerns of minority voters. “Supporting people like him and making sure we have racial justice in this country go hand in hand because everybody’s life in this country is diminished as long as these inequalities continue,” Buttigieg said in an interview. “We’ll know we’re getting where we need to be if being part of a minority — and, in particular, in this country right now being black — has no bearing on your health or your wealth or your relationship with law enforcement.” “It’s not only people of color who suffer from racial inequity. It drags down all of us,” Buttigieg continued. “I’m talking about what we’re trying to build up. And I think we can build a story about where America is headed, where everybody can see where they belong.” Buttigieg, like Sanders, Biden, Warren and Harris, will continue to have prominent voices in the 2020 conversation, having met new polling and fundraising standards to qualify for the next round of presidential debates. At the same time, several lesser-known centrists have been silenced by Democratic National Committee rules that pushed them off the debate stage altogether. Bullock, one of the castaways, fears his party isn’t doing enough to win back working class voters across the Midwest. Democratic leaders, he said, have “not incentivized actually talking to the voters that we need to win this election.” The Democrats’ search for a consistent message plays into the party’s broader quest to assemble a coalition to deny Trump reelection. Barack Obama twice won the presidency by inspiring stronger-than-normal support from young voters, minorities and working class men. That coalition failed to show up for Hillary Clinton in 2016, but young people in particular helped fuel Democrats’ success in the midterm elections last year. An estimated 31% of voters ages 18 to 29 turned out to vote in 2018, with 2 out of 3 backing Democrats, according to data compiled by the Center for Information & Research on Civil Learning and Engagement at Tufts University. Yet it’s unclear how committed Democrats are to energizing young voters in 2020.The Democratic National Committee only just recently hired its first full time staffer dedicated to youth turnout, according to Calvin Wilborn, president of the College Democrats of America. “The party is moving in the right direction. I’m not sure it’s moving fast enough,” Wilborn warned. Many liberal activists are convinced that black and Hispanic voters hold the key to Democrats’ victory in 2020. Much of the Democratic establishment, meanwhile, is far more focused on white working class men, a voting bloc that shifted