Senate Dems push new voting bill, and again hit GOP wall

If at first you don’t succeed, make Republicans vote again. That’s the strategy Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer appears to be pursuing as the New York Democrat forced another test vote Wednesday on legislation to overhaul the nation’s election laws. For the fourth time since June, Republicans blocked it. Democrats entered the year with unified, albeit narrow, control of Washington, and a desire to counteract a wave of restrictive new voting laws in Republican-led states, many of which were inspired by Donald Trump’s false claims of a stolen 2020 election. But their initial optimism has given way to a grinding series of doomed votes that are meant to highlight Republican opposition but have done little to advance a cause that is a top priority for the party ahead of the 2022 midterm elections. The Senate voted against debating voting legislation Wednesday, with Republicans this time filibustering an update to the landmark Voting Rights Act, a pillar of civil rights legislation from the 1960s. GOP senators oppose the Democratic voting bills as a “power grab.” “This is a low, low point in the history of this body,” Schumer said after the failed vote, later adding, “The Senate is better than this.” The stalemate is forcing a reckoning among Senate Democrats about whether to make changes to the filibuster rule, which requires 60 votes for legislation to advance. That could allow them to muscle legislation through but would almost certainly come back to bite them if and when Republicans take back control of the chamber. Earlier Wednesday, Schumer met with a group of centrist Democrats, including Sens. Jon Tester of Montana, Angus King of Maine, and Tim Kaine of Virginia, for a “family discussion” about steps that could be taken to maneuver around Republicans. That’s according to a senior aide who requested anonymity to discuss private deliberations. But it’s also a move opposed by moderate Sens. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona and Joe Manchin of West Virginia. Without their support, Democrats won’t have the votes needed to make a change. Time is ticking down. Redistricting of congressional districts (a once-in-a-decade process Democrats want to overhaul to make less partisan) is already underway. And the Senate poised to split town next week for a home-state work period. “Senate Democrats should stay in town and focus on the last act in this battle,” said Fred Wertheimer, who leads the good government group Democracy 21. The latest measure blocked by Republicans Wednesday is different from an earlier voting bill from Democrats that would have touched on every aspect of the electoral process. It has a narrower focus and would restore the Justice Department’s ability to police voting laws in states with a history of discrimination. The measure drew the support of one Republican, Alaska Sen. Lisa Murkowski after Democrats agreed to make changes that she sought. But all other Republicans opposed opening debate on the bill. “Every time that Washington Democrats make a few changes around the margins and come back for more bites at the same apple, we know exactly what they are trying to do,” said Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, who slammed the vote as “political theatre” on a trumped-up a “go-nowhere bill.” Murkowski, too, said she still had underlying issues with the bill as written while criticizing Schumer’s decision to force repeated “show votes.” “Let’s give ourselves the space to work across the aisle,” she said Wednesday. “Our goal should be to avoid a partisan bill, not to take failing votes over and over.” The Democrats’ John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, named for the late Georgia congressman who made the issue a defining one of his career, would restore voting rights protections that have been dismantled by the Supreme Court. Under the proposal, the Justice Department would again police new changes to voting laws in states that have racked up a series of “violations,” drawing them into a mandatory review process known as “preclearance.” The practice was first put in place under the Voting Rights Act of 1965. But it was struck down by a conservative majority on the Supreme Court in 2013, which ruled the formula for determining which states needed their laws reviewed was outdated and unfairly punitive. The court did, however, say that Congress could come up with a new formula. The bill does just that. A second ruling from the high court in July made it more difficult to challenge voting restrictions in court under another section of the law. The law’s “preclearance” provisions had been reauthorized by Congress with overwhelming bipartisan support five times since it was first passed decades ago. But after the Supreme Court’s 2013 ruling, Republican support for the measure cratered. Though the GOP has shown no indication that its opposition will waver, there are signs that some of the voting changes Democrats seek aren’t as electorally advantageous for the party as some hope. Republican Glenn Youngkin’s victory in Virginia’s Tuesday gubernatorial election offers the latest test case. Democrats took control of all parts of Virginia’s government in 2019 and steadily started liberalizing the state’s voting laws. They made mail voting accessible to all and required a 45-day window for early voting, among the longest in the country. This year they passed a voting rights act that made it easier to sue for blocking ballot access. But those changes didn’t hurt Youngkin, who comfortably beat Democrat Terry McAuliffe, a popular former governor seeking a valedictory term. That’s still unlikely to change Republicans’ calculus. “Are we all reading the tea leaves from Virginia? Yes, absolutely,” Murkowski said. “Will it be something colleagues look to? It’s just one example.” Democratic frustration is growing, meanwhile leading to increasingly vocal calls to change the filibuster. “We can’t even debate basic bills,” said Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar, a Democrat. “The next step is to work on ideas to restore the Senate.” Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

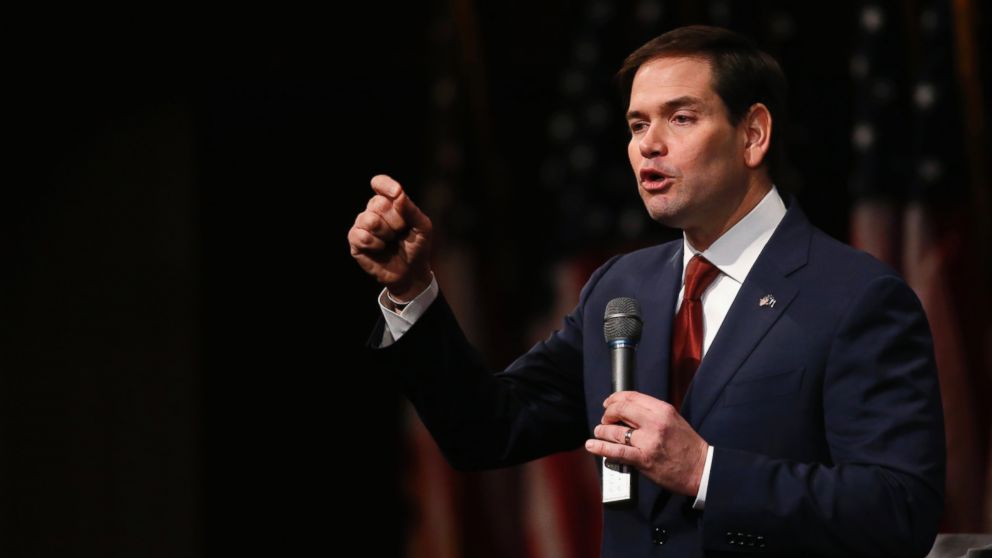

Marco Rubio donors to remain secret indefinitely

Much was made of Jeb Bush‘s relentless maneuvering when it came to early fundraising, but the actual dark money pioneer of 2016 may well be U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio. As Shane Goldmacher writes in POLITICO, the Florida senator’s top moneymen allies at Conservative Solutions Project managed to stake out a novel arrangement that will allow the sources of more than $10 million in funding for opposition research, mailers, and TV ads will remain forever unknown to the public. “It is now the model for a how a candidate can inject unlimited, secret, corrupting money into their campaigns to benefit their election,” said Fred Wertheimer, president of Democracy 21, a campaign watchdog group. “That is precisely the kind of model that we do not need in America.” The pro-Rubio nonprofit, known as the Conservative Solutions Project, was created in early 2014 and run by some of the same political operatives who would later lead for his super PAC, including South Carolina strategist Warren Tompkins. Both groups can accept unlimited donations from donors, but unlike like the super PAC, the nonprofit can keep its contributors hidden from the public — permanently. The Conservative Solutions Project operates under the “social welfare” 501(c)4 section of the tax code, which requires such groups not be primarily involved in political matters. The pro-Rubio nonprofit has claimed not to be directly involved in electoral politics. Yet the group paid for a raft of polling and research in the early primary states of Iowa, New Hampshire and South Carolina, as well as in Rubio’s home state of Florida. It bought millions in TV ads that aired in those early states, and it filled the mailboxes of Republican voters there with pro-Rubio literature. In fact, the Conservative Solutions Project was the second biggest TV advertiser of the 2016 campaign last year — trailing behind only Jeb Bush’s super PAC, according to a media tracker. Loose nonprofit tax laws, and an unusual filing schedule set up by its creators, ensure the pro-Rubio nonprofit will file little paperwork covering the primary period until April 2017 — months after the next president is sworn in. And even then, no donors will be named. “If you are trying to obscure your activities, they’re perfect,” Robert Maguire, a nonprofit investigator for the Center for Responsive Politics, said of 501(c)4s. Though a spokesman representing both Conservative Solutions Project and Rubio’s super PAC defends the “social welfare” designation saying the former was not involved in explicit electioneering, the two groups shared staffs and buildings. Their ads also aired only in states key to Rubio’s electoral success – Iowa, New Hampshire and South Carolina – where his campaign’s “3,2,1 strategy” sought to launch Rubio to the top of the GOP field. The supposed firewalls between Rubio’s political backers and backers of his social welfare rely on cutting the baloney extremely thin, writes Goldmacher: The nonprofit’s broadcast ads ran through November 22 in Iowa and New Hampshire. About a week later the Rubio super PAC picked up where it left off. The same ad buying firm, Target Enterprises, executed the ad reservations for both the Rubio super PAC and nonprofit. “They could not have been more blatant with the way this took place,” Wertheimer said. At some television stations, such as WMUR in Manchester and KCCI in Des Moines, the forms the television stations filed with the Federal Communications Commission listed the nonprofit as spending on behalf of “Marco Rubio 2016.” When that became public, the nonprofit’s attorney sent letters to some stations asking to correct those records, arguing their ads starring Rubio were not actually about Rubio. “CSP does not make candidate-related, political expenditures,” wrote Cleta Mitchell, the group’s lawyer and a prominent GOP attorney, of the Conservative Solutions Project. “All public communications are centered around important policy debates and concerns.” Some of Rubio’s rivals, particularly from the Jeb Bush camp, tried to make an issue of the questionable fundraising and disclosure tactics employed by the pro-Rubio 501(c)4. But this year’s slash-and-burn primary season was not well-suited for that kind of nuance, writes Goldmacher. Bush’s team, in particular, tried to highlight Rubio’s use of nonprofit as they battled over fundraising totals. “Haven’t seen the Rubio news release on frugality did it include the $6 million in secret money TV ads they saved money on?” as Bush communications director Tim Miller tweeted in October. The issue, however, never really broke through. “You’re talking about two of the most boring and convoluted fields of law: campaign finance and nonprofit tax law,” said Maguire, the nonprofit investigator. “Trying to explain that in an election where you have someone as outrageous as Donald Trump — it’s hard to do.”

Group backing Hillary Clinton gets $1M from untraceable donors

Hillary Rodham Clinton told a cheering crowd at her largest rally so far that “the endless flow of secret, unaccountable money” must be stopped. Two weeks later, the main super PAC backing her bid for the Democratic presidential nomination accepted a $1 million contribution that cannot be traced. The seven-figure donation, made June 29 to the pro-Clinton Priorities USA Action, came from another super political action committee, called Fair Share Action. Its two lone contributors are Fair Share Inc. and Environment America Inc., according to records filed with Federal Election Commission. Those two groups are nonprofits that are not legally required to reveal information about their donors. Such contributions are sometimes called “dark money” by advocates for stricter campaign finance rules. “This appears to be an out-and-out laundering operation designed to keep secret from the public the original source of the funds given to the super PAC, which is required to disclose its contributors,” said Fred Wertheimer, director of one such group, the Washington-based Democracy 21. Wertheimer urged Priorities to return the money and said that Clinton should demand that the super PAC “publicly disclose all of the original sources of money” of any contribution it receives. It’s a suggestion rejected by Priorities USA, whose spokesman, Peter Kauffmann, said the group is “playing by the rules.” “In the face of a billion-dollar onslaught by right-wing groups, there is too much at stake for everyday Americans for Democratic groups to unilaterally disarm,” he said. Priorities USA raised about $15.6 million in the first six months of the year. While another Democratic competitor, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, has rejected the support of super PACs altogether, Clinton has been plain that she needs big-money help. “We’re going to have to do what we can in this election to make sure that we’re not swamped by money on the other side,” she said in July. Several of the Republican candidates for president also have nonprofits dedicated to helping their candidacies. Conservative Solutions Project, a group paying for ads that boost Florida Sen. Marco Rubio, says it raised about $16 million through June. Former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush also has such a group, called Right to Rise Policy Solutions. The law does not require those nonprofits to disclose their donors, but they are limited in how much they can directly advocate for a candidate. Super PACs have much more latitude in their political activities. As a trade-off, they must report their donors to the Federal Election Commission. But as is the case with June’s $1 million donation to Priorities USA Action, sometimes the named donors are nonprofits that collect money from anonymous sources. Other times, donors to super PACs are limited liability corporations or trusts that are difficult if not impossible to trace. A prime example is Stand for Principle, a super PAC helping Republican Texas Sen. Ted Cruz. Almost all of the $250,500 the super PAC raised in the first six months of the year came from “V3 231 LLC,” a corporation made up of three other LLCs, according to federal court records reviewed by The Associated Press. Identifying the people behind an LLC can take weeks or months of intensive investigation, because corporate registration records typically identify only a street address and contact for a registered agent, usually a lawyer. Clinton’s allies have taken over Priorities USA, a super PAC that was set up in 2011 to help President Barack Obama win re-election. It’s now led by Guy Cecil, a veteran of Clinton’s 2008 presidential campaign, and her longtime advocates Harold Ickes and David Brock are among its board members. Tax and campaign finance records show Fair Share Inc. and Environment America Inc. — the nonprofit donors behind the $1 million Priorities USA contribution — did not give to Priorities USA in the Obama era. Fair Share advocates for job creation, and Environment America works on issues such as climate change. Both have existed since at least 2007. Contributions flow to both of those nonprofits thanks in part to the Democracy Alliance, a left-leaning donor network that meets privately twice a year. Brock attends most of those gatherings. David Elliot, a spokesman for the nonprofit Fair Share, said the group raises its money primarily from small donors online. Elizabeth Ouzts, a spokeswoman for Environment America, described that nonprofit’s funding as being from “itty, bitty donors,” and not big check-writers or corporations. But because neither group is required to disclose its donors to federal regulators, as required of a campaign or super PAC, those statements are impossible to verify. The Environment America money that ultimately landed in Priorities USA’s bank account was a show of support for Clinton, Ouzts said, “because she shares our priorities.” Anonymous money is helping Clinton in other ways, too. American Bridge 21st Century, founded by Brock, assists Clinton by providing her campaign and other Democrats with opposition research on Republicans. It operates both as a super PAC that reveals donors and a nonprofit that doesn’t. The latest FEC filings show that the super PAC side of American Bridge raised $5 million, and the nonprofit side gave the group about $1.2 million in overhead expenses such as office space and salaries. That nonprofit money can’t be traced to any donors. Republished with permission of The Associated Press.

Data: Nearly five dozen given a third of all 2016 campaign cash

It took Ted Cruz three months to raise $10 million for his campaign for president, a springtime sprint of $1,000-per-plate dinners, hundreds of handshakes and a stream of emails asking supporters to chip in a few bucks. One check, from one donor, topped those results. New York hedge fund magnate Robert Mercer‘s $11 million gift to a group backing the Texas Republican’s White House bid put him atop a tiny group of millionaires and billionaires whose contributions already dwarf those made by the tens of thousands of people who have given to their favorite presidential candidate. An Associated Press analysis of fundraising reports filed with federal regulators through Friday found that nearly 60 donations of a million dollars or more accounted for about a third of the more than $380 million brought in so far for the 2016 presidential election. Donors who gave at least $100,000 account for about half of all donations so far to candidates’ presidential committees and the super PACs that support them. The review covered contributions to outside groups that can accept checks of any size, known as super PACs, and to the formal campaigns, which are limited to accepting no more than $2,700 per donor. The tally includes donations from individuals, corporations and other organizations reflected in data filed with the Federal Election Commission as of Friday, the deadline for super PACs to report for the first six months of the year. That concentration of money from a small group of wealthy donors builds on a trend that began in 2012, the first presidential contest after a series of court rulings and regulatory steps that created the super PAC. They can openly support candidates but may not directly coordinate their actions with their campaigns. “We have never seen an election like this, in which the wealthiest people in America are dominating the financing of the presidential election and as a consequence are creating enormous debts and obligations from the candidates who are receiving this financial support,” said Fred Wertheimer, president of Democracy 21, a Washington-based group that wants to limit money in politics. Others see an upside to the rainmakers. “Big money gives us more competitive elections by helping many more candidates spread their message,” said David Keating, director of the Center for Competitive Politics, which advocates for fewer campaign finance limits. For any number of reasons, these donors are willing to give so generously. Some may have a business that stands to gain from an executive branch that changes how an industry is regulated, while others hope for plum administration assignments, such as a diplomatic post overseas or a cabinet position. Many say their contributions, which the U.S. Supreme Court has recognized as equivalent to free speech, merely reflect their intense belief in a particular candidate – and in the political system in general. “I’d think that the fact that I’m willing to spend money in the public square rather than buying myself a toy would be considered a good thing,” said Scott Banister, a Silicon Valley investor who gave $1.2 million to a super PAC helping Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul in the Republican presidential race. “The voters still, at the end of the day, make the decision,” he said. “You can spend $1 billion trying to tell the voters to vote for a set of ideas they don’t like, and they will still vote against the candidate.” For Florida developer Al Hoffman, financial support of the state’s former governor, Jeb Bush, is personal. A longtime friend and political contributor to the Bush family, he gave $1 million to Bush’s super PAC, contributing to its record-setting haul of $103 million in the first six months of the year. Hoffman was ambassador to Portugal during former President George W. Bush‘s second term. He said he sometimes offered Bush advice during his time as Florida’s governor, but doesn’t expect to influence a Jeb Bush administration. “I’d just like to see one,” he said. While the existence of high-dollar donors is more pronounced on the Republican side, they’re also among those giving to the super PAC backing Democratic front-runner Hillary Rodham Clinton. Seven donors of at least a million dollars accounted for almost half of the total collected by Priorities USA Action. Entertainment mogul Haim Saban and his wife, Cheryl, led with a $2 million gift, and hedge-fund billionaire George Soros, historically one of the Democratic Party’s biggest givers, donated $1 million. But no one has capitalized on the new era of big money like Bush. After announcing plans to explore a presidential run in December, Bush embarked on a nearly seven-day-a-week travel schedule to raise money for his Right to Rise super PAC. Bush navigated limits on how candidates can raise money for super PACs by playing coy about his intentions. Now that he is officially a candidate, he has left Right to Rise in the hands of his trusted strategist and friend, Mike Murphy. He’s not alone in the use of super PACs to fuel a presidential run. New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie and Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker are too new to the presidential contest, announcing only weeks ago, to have filed any reports about their campaigns’ finances. Yet super PACs that sprang up months ago to support them show their efforts will be financially viable: A group backing Christie raised $11 million, while two supporting Walker brought in $26 million. Such totals put them well ahead of Paul, former technology executive Carly Fiorina, former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee and former Sen. Rick Santorum – who all began their presidential campaigns in the spring. Cruz’s super PACs, meanwhile, didn’t just get the $11 million from Mercer. They also received a $10 million donation from Toby Neugebauer, an energy investor in Texas, while the Texas-based Wilks family pooled together a $15 million gift. Super PACs will spend as campaigns do, investing in polling and data sets, hiring employees in key states and buying pricey television and digital advertising, direct mailings and phone calls to voters.

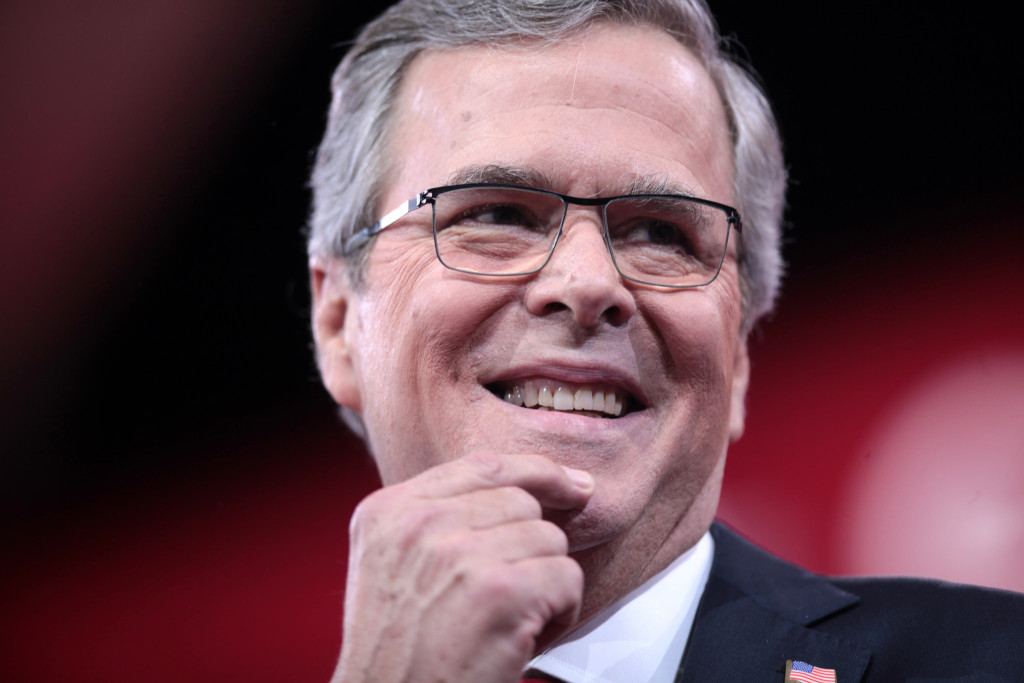

Jeb Bush preparing to delegate many campaign tasks to super PAC

Jeb Bush is preparing to embark on an experiment in presidential politics: delegating many of the nuts-and-bolts tasks of seeking the White House to a separate political organization that can raise unlimited amounts of campaign cash. The concept, in development for months as the former Florida governor has raised tens of millions of dollars for his Right to Rise super PAC, would endow that organization not just with advertising on Bush’s behalf, but with many of the duties typically conducted by a campaign. Should Bush move ahead as his team intends, it is possible that for the first time a super PAC created to support a single candidate would spend more than the candidate’s campaign itself — at least through the primaries. Some of Bush’s donors believe that to be more than likely. The architects of the plan believe the super PAC’s ability to legally raise unlimited amounts of money outweighs its primary disadvantage, that it cannot legally coordinate its actions with Bush or his would-be campaign staff. “Nothing like this has been done before,” said David Keating, president of the Center for Competitive Politics, which opposes limits on campaign finance donations. “It will take a high level of discipline to do it.” The exact design of the strategy remains fluid as Bush approaches an announcement of his intention to run for the Republican nomination in 2016. But at its center is the idea of placing Right to Rise in charge of the brunt of the biggest expense of electing Bush: television advertising and direct mail. Right to Rise could also break into new areas for a candidate-specific super PAC, such as data gathering, highly individualized online advertising and running phone banks. Also on the table is tasking the super PAC with crucial campaign endgame strategies: the operation to get out the vote and efforts to maximize absentee and early voting on Bush’s behalf. The campaign itself would still handle those things that require Bush’s direct involvement, such as candidate travel. It also would still pay for advertising, conduct polling and collect voter data. But the goal is for the campaign to be a streamlined operation that frees Bush to spend less time than in past campaigns raising money, and as much time as possible meeting voters. Bush’s plans were described to The Associated Press by two Republicans and several Bush donors familiar with the plan, who spoke on condition of anonymity because the former Florida governor has not yet announced his candidacy. “This isn’t the product of some genius thinking,” said a Republican familiar with the strategy. “This is the natural progression of the rules as they are set out by the FEC.” Bush spokeswoman Kristy Campbell said: “Any speculation on how a potential campaign would be structured, if he were to move forward, is premature at this time.” The strategy aims to take maximum advantage of the new world of campaign finance created by a pair of 2010 Supreme Court decisions and counts on the Federal Election Commission to remain a passive regulator with little willingness to confront those pushing the envelope of the law. One reason Bush’s aides are comfortable with the strategy is because Mike Murphy, Bush’s longtime political confidant, would probably run the super PAC once Bush enters the race. Meanwhile, David Kochel, a former top adviser to Mitt Romney‘s campaigns and an ally of Bush senior adviser Sally Bradshaw, would probably be the pick to lead Bush’s official campaign. “Every campaign is going to carefully listen to the lawyers as to what is the best way to allocate their resources and how to maximize them,” said Al Cardenas, former chairman of the American Conservative Union and a Bush adviser. “Nobody wants to relinquish any advantage.” For Bush, the potential benefits are enormous. Campaigns can raise only $2,700 per donor for the primary and $2,700 for the general election. But super PACs are able to raise unlimited cash from individuals, corporations and groups such as labor unions. In theory, that means a small group of wealthy Bush supporters could pay for much of the work of electing him by writing massive checks to the super PAC. Bush would begin a White House bid with confidence that he will have the money behind him to make a deep run into the primaries, even if he should stumble early and spook small-dollar donors, starving his own campaign of the money it needs to carry on. Presidential candidates in recent elections have also spent several hours each day privately courting donors. This approach would not eliminate that burden for Bush, but would reduce it. “The idea of a super PAC doing more … means the candidate has to spend less time raising money and can spend more time campaigning,” said longtime Mitt Romney adviser Ron Kaufman, who supports Bush. The main limitation on super PACs is that they cannot coordinate their activities with a campaign. The risk for Bush is that his super PAC will not have access to the candidate and his senior strategists to make pivotal decisions about how to spend the massive amount of money it will take to win the Republican nomination and, if successful, secure the 270 electoral votes he will need to follow his father and brother into the White House. “The one thing you give away when you do that is control,” Kaufman said. Bush will also be dogged by advocates of campaign finance regulation. The Campaign Legal Center, which supports aggressive regulation of money and politics, has already complained to the FEC that Bush is currently flouting the law by raising money for his super PAC while acting like a candidate for president. Others are on guard, too. “In our view, we are headed for an epic national scandal,” said Fred Wertheimer, president of the pro-regulation group Democracy 21. “We intend to carefully and closely monitor all the candidates and their super PACs, because they will eventually provide numerous examples of violations.” All of the major candidates for president