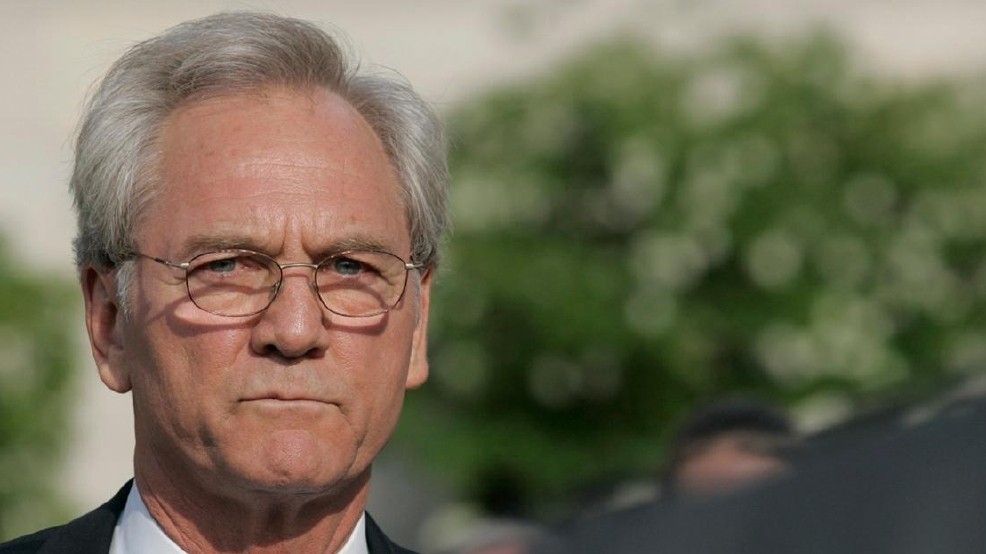

Doug Jones introduces bill to open civil rights cold case files, written by HS students

Alabama U.S. Sen. Doug Jones introduced a bill on Tuesday that would mandate the release of government records related to unsolved civil rights cases — a bill written by a group of high school students. Jones worked with a group of students from Hightstown High School in Hightstown, N.J., and their civics and government teacher, Stuart Wexler in drafting and introducing the bill the students first envisioned in their Advanced Placement U.S. Government classroom. Jones says the legislation is necessary because the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), as implemented, has prevented the timely and adequate disclosure of executive branch records, and congressional records are not subject to public disclosure under FOIA. FOIA documents are also notoriously redacted beyond practical use. The bill, the Civil Rights Cold Case Records Collection Act of 2018, if passed, remedies this problem by requiring the National Archives and Records Administration to create a collection of government documents related to civil rights cold cases and to make those documents available to the public. For Jones, the issue is personal Prior to his time in the Senate, Jones, a former prosecutor, is best known for prosecuting Ku Klux Klansmen responsible for killing four black girls in the 1963 bombing of the 1963 Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham as a U.S. attorney. “Having prosecuted two civil rights cold cases in Alabama, I know firsthand the importance of having every available piece of information at your disposal,” Jones said. “This bill will ensure public access to records relating to these cases and will expand the universe of people who can help investigate these crimes, including journalists, historians, private investigators, local law enforcement, and others.” Jones continued, “We might not solve every one of these cold cases, but my hope is that this legislation will help us find some long-overdue healing and understanding of the truth in the more than 100 unsolved civil rights criminal cases that exist today.” In 2007, Jones testified to the House Judiciary Committee in support of the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crimes Act that established a special initiative in the U.S. Department of Justice to investigate civil rights cold cases. He spoke about the difficulty of prosecuting these cases so many years after the crimes were committed and pointed to the importance of sharing information in order to find the truth. Jones is not the only one who believes in the importance of his bill. Hank Klibanoff, Director, Georgia Civil Rights Cold Cases Project at Emory University, says if passed it would “have on thousands of families.” “It is hard to overstate the positive impact that Sen. Doug Jones’s proposed Civil Rights Cold Case Records Collection Act would have on thousands of families who, 40 to 60 years later, have no idea how a father, grandfather, aunt or brother came to a violent death in the modern civil rights era,” said Klibanoff. “As a journalist and historian who relies on government-held records in these civil rights cold cases, it’s important to know that our purposes are simple: To learn the truth, to seek justice where there may be a living perpetrator, to tell the untold stories, and to bring closure to families of victims, and find opportunities for racial reconciliation.” The details The Civil Rights Cold Case Records Collection Act of 2018 will: Require the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) to establish a collection of cold case records about unsolved criminal civil rights cases that government offices must publicly disclose in the collection without redaction or withholding. Establish a Civil Rights Cold Case Records Review Board as an independent agency of impartial private citizens to facilitate the review, transmission to NARA, and public disclosure of government records related to such cases. Read a detailed overview of the legislation here. Watch Jones testify before the House Judiciary Committee in 2007:

US sets new record for censoring, withholding government files

The federal government censored, withheld or said it couldn’t find records sought by citizens, journalists and others more often last year than at any point in the past decade, according to an Associated Press analysis of new data. The calculations cover eight months under President Donald Trump, the first hints about how his administration complies with the Freedom of Information Act. The surge of people who sought records but ended up empty-handed was driven by the government saying more than ever it could not find a single page of requested files and asserting in other cases that it would be illegal under U.S. laws to release the information. People who asked for records under the Freedom of Information Act received censored files or nothing in 78 percent of 823,222 requests, a record over the past decade. When it provided no records, the government said it could find no information related to the request in a little over half those cases. It turned over everything requested in roughly one of every five FOIA requests, according to the AP analysis. Records requests can take months — even years — to get fulfilled. Even then, the government censored documents in nearly two-thirds of cases when it turned over anything. The federal government also spent $40.6 million last year in legal fees defending its decisions to withhold federal files, also a record. That included the time when a U.S. judge ruled against the AP and other news organizations asking for details about who and how much the FBI paid to unlock the iPhone used by a gunman in a mass shooting in San Bernardino, California. When the government loses in court, it sometimes must pay the winner’s attorney’s fees. For example, the New York Times was awarded $51,910 from the CIA in May in a fight over records about chemical weapons in Iraq. It was impossible, based on the government’s own accounting, to determine whether researchers, journalists and others asked for records that did not actually exist or whether federal employees did not search hard enough before giving up. The government said it found nothing 180,924 times, an 18 percent increase over the previous year. “Federal agencies are failing to take advantage of modern technology to store, locate and produce records in response to FOIA requests, and the public is losing out as a result,” said Adam A. Marshall, the Knight Foundation litigation attorney at the Washington-based Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. He said citizens and others should try to precisely describe how they want filings cabinets, hard drives or email accounts searched, but “you shouldn’t have to be an expert in records management just to submit a FOIA.” In other cases, the times the government said it would be illegal under other U.S. laws to release requested information nearly doubled to 63,749. Those laws include broad prohibitions against revealing details about U.S. intelligence activities or foreign governments, trade secrets, individual banking or tax records and more. Many of those requests probably involved files related to the U.S. investigation into how Russia interfered in the 2016 presidential election or the related grand jury investigations or about Trump’s personal or business tax returns, said Kel McClanahan, a Washington lawyer who frequently sues the U.S. government for records. “How many people do you think asked for Trump’s tax returns?” he asked. A disturbing trend continued: In more than one-in-three cases, the government reversed itself when challenged and acknowledged that it had improperly tried to withhold pages. But people filed such appeals only 14,713 times, or about 4.3 percent of cases in which the government said it found records but held back some or all of the material. The Trump administration, in a new report last week, noted that it received a record number of information requests last year. It said many agencies reduced their backlogs of overdue requests. The administration also said it was directing federal agencies to improve the number of requests they process and do some more quickly. Performance under the records law by the Trump administration has been a source of curiosity, since Trump has eschewed some of the common conventions of transparency. For example, the president has declined to release his personal tax returns or logs of official visitors to the White House, and ethics waivers granted to many of Trump’s political appointees do not include details about their former or current corporate clients. But Trump is personally more accessible to reporters asking questions than President Barack Obama, and he released as many details about his medical records as previous presidents. The Freedom of Information Act figures, released Friday, cover the actions of 116 departments and agencies during the fiscal 2017, which ended Sept. 30. The highest number of requests went to the departments of Homeland Security, Justice, Defense, Health and Human Services, and Agriculture, along with the National Archives and Records Administration and Veterans Administration. The administration released its figures ahead of Sunshine Week, when news organizations promote open government and freedom of information. Under the records law, citizens and foreigners can compel the U.S. government to turn over copies of federal records for no or little cost. Anyone who seeks information through the law is generally supposed to get it unless disclosure would hurt national security, violate personal privacy, or expose business secrets or confidential decision-making in certain areas. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

You can count gigabit broadband subscribers in Alabama’s ‘Gig City’ on one finger

If you build it, sometimes they don’t come. Opelika spent about $43 million to build a broadband network capable of 1 gigabit-per-second symmetrical speeds, financed by a bond issue backed up by the revenue of Opelika Power Services. Four years later (as of Aug. 26), OPS has one subscriber for its Lite Speed Gig service and none for its next highest tier, Lite Speed Plus, with upload and download speeds of 300 megabits per second. David Williams, president of the Taxpayers Protection Alliance, said he’s not surprised. “You put in this expensive service and people aren’t going to pay $500 a month for a gig,” he said. “All that glitters is not gold. Just because you create the gig service doesn’t mean people are going to use it.” “How do you justify the costs to taxpayers when one person is using the gig service?” Williams asked. Watchdog.org received the subscriber numbers from OPS through a Freedom of Information Act request. OPS Director Derek Lee, who emailed the numbers, didn’t respond to a request to discuss how subscriber numbers correlate with plans to pay back the bond debt. Opelika Mayor Gary Fuller told Watchdog.org via email that “we’ll begin our fourth year of operation in October and we are on pace with our five-year plan to be at break even.” Fuller also told Business Alabama in 2014 he thought the city would break even on its broadband over the next four years, with future profits being sent to the city general fund. “It takes quite a bit of courage to take a $43 million bite out of that apple,” he told the media outlet. Voters approved the plan via referendum in 2010. OPS’s broadband service has 2,717 subscribers overall in a city of about 30,000 residents, with the majority of those subscribing to the $44.95-per-month Lite Choice service. The breakdown is as follows: Lite Essential – 661 ($34.95 per month residential, 10 mbps download/5 mbps upload) Lite Choice – 1,548 ($44.95, 30/15) Lite Ultra – 485 ($64.95, 50/25) Lite Speed – 22 ($99.95, 110/50) Lite Speed Plus – 0 ($249.95, 300/300) Lite Speed Gig – 1 ($499.95 1,000/1,000 At residential broadband pricing, these numbers would represent about $127,000 in monthly revenue, or about $1.5 million per year, though many subscribers also likely bundle their internet with cable and/or home phone service. Cable packages range from $50 to $80 per month, and phone packages between $20 and $40 per month. The total gross revenue could also be marginally higher because OPS charges more for business clients and Watchdog.org didn’t request subscriber numbers broken down by customer type. But these numbers also don’t account for the costs of operating and maintaining the network. Watchdog plans to file another FOIA to get more detailed numbers of how much OPS reaps in broadband revenue. T. Randolph Beard, an Auburn University economics professor who has written op-eds opposing expansion of government broadband, told Watchdog that people can easily stream movies — one of the most data-heavy uses of home internet — on multiple devices at minimum broadband speeds. “I’m not shocked [at the subscriber numbers] because those are enterprise services,” he said of speeds approaching a gig. “There are a very small number of customers who would need something like that.” OPS marketing manager June Owens previously told Watchdog the utility charges $2,700 a month for business customers of the gig service, which may be pricing them out of the market. Beard notes that governments say they need to build broadband networks to serve their citizens, but the very threat of a taxpayer- or ratepayer-backed network can easily scare off private providers from entering a market in the first place. “There’s a kind of ironic self-fulfilling prophecy,” he said. State Sen. Tom Whatley, R-Auburn, whose district includes Opelika, is likely to file legislation in 2017 that would allow OPS to expand into rural areas around the city. That bill would apply to any other municipal broadband network that wished to expand, as well. Beard said that would be unwise. “The track record is so bad,” he said. “I don’t think making the mistake bigger is a good idea.” • • • This article originally appeared on American Spectator via Watchdog.org. Johnny Kampis is a content editor and staff writer at Watchdog.org.

“Stunning contradiction” in many states’ records laws: Legislatures frequently exempt themselves

State capitols are often referred to as “the people’s house,” but legislatures frequently put up no-trespassing signs by exempting themselves from public-records laws. That tendency was apparent when The Associated Press sought emails and daily schedules of legislative leaders in all 50 states. The request was met with more denials than approvals. Some lawmakers claimed “legislative immunity” from the public-records laws that apply to most state and local officials. Others said secrecy was essential to the deliberative process of making laws. And some feared that releasing the records could invade the privacy of citizens, creating a “chilling effect” on the right of people to petition their government. Without access to such records, it’s harder for the public to know who is trying to influence their lawmakers on important policy decisions. “The public has a right to know what their elected officials are doing, because it’s the people’s job to hold those folks politically accountable,” said Peter Scheer, executive director of the First Amendment Coalition, a San Rafael, California-based nonprofit that advocates for greater openness in government. All legislatures allow people to watch and listen to their debates. But an AP review of open-government policies found that many state legislatures allow closed-door caucus meetings in which a majority of lawmakers discuss policy positions before public debates. Others have restrictions on taking photos and videos of legislative proceedings. In some places, lawmakers have no obligation to disclose personal financial information that could reveal conflicts of interest. Legislators possess the power to change that but are sometimes reluctant to act. A bill advancing this year in Massachusetts, for example, would strengthen the state’s public-records laws by limiting fees and setting new deadlines for state agencies and municipalities to comply. Yet it would continue to exempt lawmakers. That mirrors the way things work in Washington, D.C. Congress exempted itself when it passed the national Freedom of Information Act 50 years ago. The president and his immediate staff also are exempt. By contrast, many governors are subject to state sunshine laws. In many states, the public-records requirements passed by lawmakers present “a stunning contradiction,” said Charles Davis, dean of the College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia and a former executive director of the National Freedom of Information Coalition. “I have just always found it astonishing that they would put those requirements on public officials throughout government and exempt themselves at the same time,” he said. To gauge compliance with public-records laws, the AP sent requests to the top Democratic and Republican lawmakers in all states and most governors seeking copies of their daily schedules and emails from their government accounts for the week of Feb. 1 to Feb. 7. Of the more than 170 lawmakers who responded by mid-March, a majority denied the requests by claiming they were legally exempt. The governors were slower to respond but more often provided the information. The legislative denials came from lawmakers of both parties, although slightly more from Republicans. In states where some lawmakers said “yes” and others “no,” it was more often the majority party lawmakers who denied the requests while a minority party leader complied. In Missouri, Senate President Pro Tem Ron Richard was asked in front of dozens of reporters and editors whether he would release his government emails and daily calendars. “All you have to do is ask for it, and I’ll give it to you. I don’t care,” Richard told those attending a statewide press association event in February. Yet when the AP subsequently submitted an open-records request, Richard reversed course. A Senate administrator responded on his behalf with a letter saying that individual lawmakers aren’t subject to the Missouri Sunshine Law. Richard, who is in his first year as the Senate’s top lawmaker, explained that he learned his predecessors had determined they were exempt, and he didn’t want to break with precedent. “I’m telling you I don’t hide anything in my emails. I just don’t do that,” said Richard, a Republican from Joplin. Mississippi House Speaker Philip Gunn responded with a denial letter asserting his emails and calendars were his personal property, not subject to the Mississippi Public Records Act and protected “under the doctrine of legislative immunity” dating back hundreds of years to English common law. Denial letters on behalf of Illinois’ top Democratic and Republican lawmakers said, among other things, that releasing the records could amount to a “clearly unwarranted invasion of personal privacy” for individuals who contacted lawmakers without expecting their names to appear in the news media. An attorney for Kentucky’s legislature said secrecy was needed “to encourage effective and frank communications.” “Arranging honors for our fallen heroes, seeking options for Kentuckians with substance abuse problems or counseling citizens regarding confidential problems are all in a day’s work for our members,” wrote Kentucky legislative general counsel Morgain Sprague. “These communications have always been protected by law.” If lawmakers followed the same open-records rules that apply to others in government, the potential for some sensitive content being revealed would not be a reason for denying access to all of their emails. Rather, they could redact or withhold particular emails covered by various sunshine law exceptions while releasing the rest. In several states, lawmakers who provided their records did withhold certain emails that they considered to be exempt from disclosure. Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, who is the Republican head of the Senate, released 48 pages of emails but withheld the rest pending a request for a state attorney general’s opinion on whether confidential communications between elected officials and citizens are shielded from disclosure. New Mexico lawmakers released hundreds of emails, mainly from constituents, but withheld three under an exemption for correspondence with certain legislative staff. They also released copies of their daily calendars showing breakfasts and dinners sponsored by industry and interest groups. Lawmakers in Florida, which has one of the more expansive sunshine laws, freely released emails from people urging them to support or oppose particular bills. They also released calendars showing

Hillary Clinton emails: GOP sues, senators press attorney general

Republican senators pressed for more information Wednesday about an FBI investigation into the potential mishandling of sensitive information that passed through former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton‘s private email server, and their party sued for copies of the messages. The Republican National Committee filed two lawsuits in U.S. District Court in Washington over access to electronic messages sent or received by the Democratic presidential candidate and her top aides during her time as the nation’s top diplomat. Both spring from Freedom of Information Act requests filed last year seeking copies of emails and text messages. In court filings, the GOP says it has not received any documents in response to the requests. The GOP litigation brings the total to at least 34 civil suits so far involving requests for federal records related to Clinton’s service as secretary of state between 2009 and 2013. The Associated Press is among those with a pending case at the Washington courthouse. “For too long the State Department has undermined the public and the media’s legitimate right to records under the Freedom of Information Act, and it’s time it complies with the law,” said RNC Chairman Reince Priebus. The State Department has released more than 52,000 pages of Clinton’s work-related emails, but her private lawyers have withheld thousands more that they deemed to be personal communications unrelated to her job. Also left unresolved are questions about how Clinton and her closest aides handled classified information. The AP last year discovered Clinton’s use of the private email server, which had been set up in the basement of Clinton’s New York home by former State Department staffer Bryan Pagliano, for her to use exclusively for her work-related emails while she was secretary. The FBI for months has investigated whether sensitive information that flowed through Clinton’s email server was mishandled. The State Department has acknowledged that some emails included classified information, including at the top-secret level. Clinton has said she never sent or received anything that was marked classified at the time. The inspectors general at the State Department and for U.S. intelligence agencies are separately investigating whether rules or laws were broken. Members of the Senate Judiciary Committee questioned Attorney General Loretta Lynch on Wednesday about media reports that the Justice Department had offered Pagliano immunity from criminal prosecution in exchange for his cooperation. Pagliano previously declined to testify before Congress, citing his Fifth Amendment rights against self-incrimination. Sen. Chuck Grassley, the committee chairman, asked Lynch whether Pagliano’s immunity offer carried over to congressional committees. Grassley, R-Iowa, wants to recall Pagliano to testify if he has received immunity. Lynch declined to answer the question. “We don’t go into details with the agreements that we have with any witness on any matter in ongoing investigations,” the attorney general said. “The consistency with which the department handles ongoing matters, whether they involve a famous last name (or not), is something that we take very seriously,” Lynch said. “We treat them the same, and that is how the public takes confidence in the investigations we conduct.” Lynch also said she had not discussed the email investigation with anyone at the White House and did not plan to do so. Republished with permission of the Associated Press.

Former Gov. Don Siegelman’s son seeks records about father’s prosecution

The son of former Gov. Don Siegelman has filed a lawsuit seeking Department of Justice documents about his father’s prosecution. The lawsuit filed Tuesday in Birmingham federal court accuses the Department of Justice and its Office of Professional Responsibility of improperly withholding records the family has sought through public records requests. According to the lawsuit, Joseph Siegelman last year filed a records request for documents related to the office’s review of prosecutors’ behavior in the case. The lawsuit said the request was denied because of Freedom of Information Act exemptions for protected communications between agencies, law enforcement records and information that invades a person’s privacy. A federal jury convicted Siegelman in 2006 of bribery and obstruction of justice. The former governor is serving a 6 1/2 year prison sentence. Republished with permission of the Associated Press.

Hillary Clinton, aides stressed protecting State Dept info in email

Hillary Rodham Clinton and her aides at the State Department were acutely aware of the need to protect sensitive information when discussing international affairs over email and other forms of unsecure electronic communication, according to the latest batch of messages released by the agency from Clinton’s tenure as secretary of state. The State Department made public roughly 7,121 pages of Clinton’s emails late Monday night, including 125 emails that were censored prior to their release because they contain information now deemed classified. The vast majority concerned mundane matters of daily life at any workplace: phone messages, relays of schedules and forwards of news articles. But in a few of the emails, Clinton and her aides noted the constraints of discussing sensitive subjects when working outside of the government’s secure messaging systems – and the need to protect such information. Senior adviser Alec Ross, in a February 2010 email intended for Clinton, cited frustration with “the boundaries of unclassified email” in a message about an unspecified country, which Ross referred to as “the country we discussed.” The email appears to focus on civil unrest in Iran during the period preceding the Green Movement, when Iranian protesters used social media and the Internet to unsuccessfully challenge the re-election of then-President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. In an exchange from Feb. 6, 2010, Clinton asks aide Huma Abedin for talking points for a call she’s about to have with the newly appointed foreign minister of Ecuador. “You are congratulating him on becoming foreign minister, and purpose is to establish a personal relationship with him,” Abedin replied. “Trying to get u call sheet, its classified….” In another email from January 2010, Clinton aide Cheryl Mills responds angrily to a New York Times story based on leaked classified cables sent by Karl Eikenberry, the U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan. “The leaking of classified material is a breach not only of trust, it is also a breach of the law,” Mills wrote. Clinton also expressed frustration with the State Department’s treatment of certain ordinary documents as classified. After an aide noted the draft of innocuous remarks about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was on the State Department’s classified messaging system, she responded, “It’s a public statement! Just email it.” Sent a moment later, the statement merely said that U.S. and British officials would work together to promote peace. “Well that is certainly worthy of being top secret,” Clinton responded sarcastically. All those email conversations with Clinton took place via her private email account, highlighting the challenge the front-runner for the Democratic presidential nomination faces as she struggles to explain her decision to set up a private email server at her New York home. She now says her decision to use a personal email account to conduct government business was a mistake. Government employees are instructed not to paraphrase or repeat in any form any classified material via unsecured email, which includes both the official state.gov email system and the account Clinton ran on her private server. State Department spokesman Mark Toner said Monday none of the information censored in Monday’s release was identified as classified when the emails were sent or received by Clinton, noting the redactions were made subsequently and only prior to the release of the emails under the Freedom of Information Act. In total, the State Department has now released 13,269 pages of Clinton’s emails, more than 25 percent of the total that she turned over from her private server, Toner said. Clinton provided the department some 30,000 emails she categorized as work-related late last year, while deleting a similar amount from her server because she said they were solely personal in nature. Clinton’s use of a private email may have created logistical problems communicating with State Department aides. “Well its clearly a state vs outside email issue,” wrote Abedin in August 2010, after another aide reported missing some messages from Clinton. “State has been trying to figure it out. So lj is getting all your emazils cause she’s on her personal account too.” Despite approving the creation of a relatively complex email system in her home, Clinton seemed puzzled by basic technology. In a July 2010 exchange, Clinton quizzed former staffer Philippe Reines on how to charge the Apple tablet and update an application. Reines asks Clinton if she has a wireless Internet connection, and she replies: “I don’t know if I have wi-fi. How do I find out?” A few of the messages released Monday hint at the ways Clinton’s family was involved in her work at the agency. Following the devastating Haiti earthquake in January 2010, Clinton wrote about her efforts to involve Bill Clinton in the disaster response. After an unnamed party assumed that former President Clinton’s preexisting role as a United Nations envoy to Haiti would sideline him from the reconstruction effort, Hillary stepped in. “I just spent an extra hour explaining the architecture” of the relief organizations, Clinton wrote. “Will fill wjc in on the plane.” Bill Clinton, who is often referred to by his initials “WJC,” ended up as co-chairman of the Interim Haiti Recovery Commission, a body with significant power over reconstruction funds. An email from Chelsea Clinton, addressed to “Dad, Mom,” offers a densely-written, seven-page assessment of conditions on the ground in Haiti based on her “data set and its clear limitations” after she took a four-day trip to the devastated island. “Please do not forward this in whole or in part attributed to me without asking me first,” she writes to her parents, saying she’s “happy to be an invisible soldier.” Republished with permission of the Associated Press.

Probe of Hillary Clinton’s server could find more than just emails

Now that federal investigators have Hillary Rodham Clinton‘s homebrew email server, they could examine files on her machine that would be more revelatory than the emails themselves. Clinton last week handed over to the FBI her private server, which she used to send, receive and store emails during her four years while secretary of state. The bureau is holding the machine in protective custody after the intelligence community’s inspector general raised concerns that classified information had traversed the system. Questions about her use of the server have shadowed her campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination. Clinton again this weekend repeated a carefully constructed defense of her actions, in that she did not send or receive emails marked classified at the time. But her emails show some messages she wrote were censored by the State Department for national security reasons before they were publicly released. The government blacked out those messages under a provision of the Freedom of Information Act intended to protect material that had been deemed and properly classified for purposes of national defense or foreign policy. What hasn’t been released: data that could show how secure her system was, whether someone tried to break in, and who else had accounts on her system. A lawyer for Platte River Networks, a Colorado-based technology services company that began managing the Clinton server in 2013, said the server was provided to the FBI last week. Indeed, many physical details of the server remain unknown, such as whether its data was backed up. In March, The Associated Press discovered that her server traced back to an Internet connection at her home in Chappaqua, New York. A computer server isn’t a marvel of modern technology. Just like a home desktop, the computer’s data is stored on a hard drive. It’s unclear whether the drive that Clinton used was thoroughly erased before the device was turned over to federal agents. If it had been, it’s also uncertain whether the FBI could recover the data. Clinton’s lawyer has used a precise term, “wiped,” to describe the deleted emails, but it was not immediately clear whether the server had been wiped. Such a process overwrites deleted content to make it harder or impossible to recover. An FBI spokesman declined to comment. Investigators who examine her server might find all sorts of information – how it was configured, whether it received necessary security updates to fix vulnerabilities in software, or whether anyone tried to access it without permission. Running a server is akin to her messages being stored inside an office file cabinet. But while a file cabinet only yields the documents stored inside, a server can also offer information about the use of that data over time: Who had access to the filing cabinet? Did anyone try to pick the lock? Did the owner attempt to alter the files in any way? And who was given keys to the building in the first place? Since her server was first installed in 2009, it most likely used a traditional hard disk-based device rather than a newer solid state unit that only has become commonly used in the last two or three years, said computer scientist Darren Hayes. Solid state drives, until recently, were much more expensive than their counterparts for storing lots of data. Forensics experts would then have an easier time retrieving erased data because such older, disk-based servers are not as efficient in deleting material, said Hayes, assistant professor and director of cybersecurity at Pace University’s School of Computer Science and Information Systems in New York. “A hard disk drive is very difficult to manipulate,” he said. “Once you get your hands on a hard drive, there’s a lot you can recover.” Even after files are marked for deletion on a disk, Hayes said, their contents remain on the drive and can be retrieved. Even if the full file is gone, fragments can be pulled off the drive. Sometimes a complete email file even can be found inside other files marked for deletion. Clinton said in March that she had exchanged about 60,000 emails during her four years in the Obama administration, about half of which were personal and deleted. She turned over the others to the State Department, which is reviewing and releasing them on a monthly basis. Last month, the inspector general for the nation’s intelligence community warned that some of the information that passed through Clinton’s server was classified information. It’s generally not possible to forward or cut-and-paste an email marked classified to a private account because classified email systems are closed to outsiders. But it can be illegal to paraphrase or retype classified information from a secure email into an unprotected message sent to a personal address. Hayes said forensics experts could, in most cases, determine whether the server used encryption to transmit emails, which would be important in learning whether her occasional email discussions of classified and sensitive matters might have been vulnerable to hackers and snooping by foreign governments. The server’s internal registry could also provide hints of whether hackers penetrated the server’s security. “They may have deleted a lot of data, but there’s a lot of data that a good forensics team would be able to recover,” he said. Republished with permission of The Associated Press.

State official: Hillary Clinton’s email practices “not acceptable”

A high-ranking State Department official said Wednesday it’s “not acceptable” for any agency employee to conduct government business on a private email server as former Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton did. Joyce Barr, the agency’s chief freedom of information officer, made the comment under questioning from Republican senators who used a Senate Judiciary hearing on open records laws to attack Clinton over her email practices. Sen. John Cornyn of Texas said that Clinton’s approach amounted to a “premeditated and deliberate” attempt to avoid open records requirements. Sen. Thom Tillis of North Carolina said that anyone who took such an approach should be fired, and asked Barr whether it would be considered acceptable. Barr said that she had not been aware of Clinton’s decision to conduct all her State Department email on a private server but that the agency has now made it clear to employees that such an approach would not be acceptable. “I think that the actions that we’ve taken in the course of recovering these emails have made it very clear what people’s responsibilities are with regard to record-keeping,” she said. “We continue to do training, we’ve sent department notices, telegrams, we’ve talked to directors and I think the message is loud and clear that that is not acceptable.” Clinton, who is running for president, has defended using a personal email account while serving as secretary of state as a matter of personal convenience. She says she has turned over to the State Department all work-related emails — more than 30,000 of them — though House Republicans investigating the 2012 attacks on the U.S. mission in Benghazi, Libya, are demanding more. They insist the server itself should be examined by a third party. A spokesman for Clinton’s campaign declined comment. Clinton has agreed to testify on Capitol Hill later this month at the request of the special committee investigating the Benghazi attacks. Barr acknowledged problems with the State Department’s overall performance responding to open records requests, calling an existing backlog of 18,000 requests “unacceptable.” But she insisted improvements were being made even as the number of requests keeps growing and the agency is understaffed. Like other government agencies, the State Department is bound by laws including the Freedom of Information Act that generally require them to maintain records and make them available to the public when asked, with some exceptions. Karen Kaiser, general counsel at The Associated Press, testified that despite promises of greater transparency by the Obama administration, most agencies are not abiding by their legal obligations under open records laws. “Non-responsiveness is the norm, and the reflex at most agencies is to withhold information, not to release it,” she told senators. Lawmakers are weighing legislation to improve the Freedom of Information Act, but Kaiser said agencies should also be made to comply with the laws already enacted. “We can have all the wonderful laws on the books and the presumptions of disclosure written in, but if the agencies don’t abide by the requirements we’re in a bad position,” she said. Republished with permission of The Associated Press.