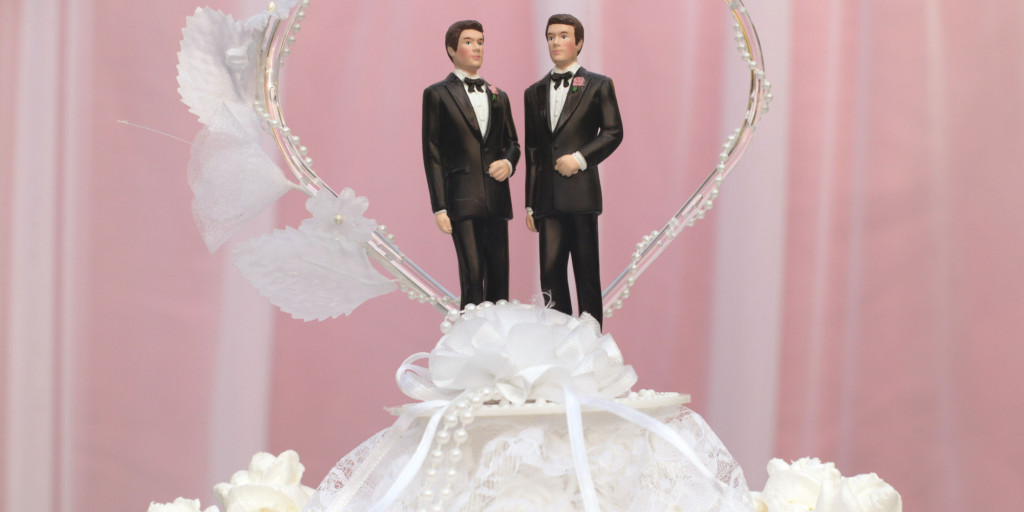

What’s at stake in U.S. Supreme Court gay marriage arguments

Just two years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down part of the federal anti-gay marriage law that denied a range of government benefits to legally married same-sex couples. The decision in United States v. Windsor did not address the validity of state marriage bans, but courts across the country, with few exceptions, said its logic compelled them to invalidate state laws that prohibited gay and lesbian couples from marrying. The number of states allowing same-sex marriage has grown rapidly. As recently as October, a little more than one-third of the states permitted same-sex marriage. Now, same-sex couples can marry in 36 states and the District of Columbia. A look at what is now before the Supreme Court, and the status of same-sex marriage around the country: • • • What’s left for the Supreme Court to do amid all this change? The justices on Tuesday are hearing extended arguments, scheduled to run 2½ hours, in highly anticipated cases about the right of same-sex couples to marry. The cases before the court come from Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio and Tennessee, all of which had their marriage bans upheld by the federal appeals court in Cincinnati in November. That appeals court is the only one that has ruled in favor of the states since the 2013 Windsor decision. • • • What’s at stake? Two related issues would expand the marriage rights of same-sex couples. The bigger one: Do same-sex couples have a constitutional right to marry or can states continue to define marriage as the union of a man and a woman? The second: Even if states won’t allow some couples to marry, must they recognize valid same-sex marriages from elsewhere? • • • What are the main arguments on each side? The arguments of marriage-rights supporters boil down to a claim that states lack any valid reason to deny the right to marry, which the court has earlier described as fundamental to the pursuit of happiness. They say state laws that allow only some people to marry violate the Constitution’s guarantee of equal protection under the law and make second-class citizens of same-sex couples and their families. Same-sex couples say that preventing them from marrying is akin to a past ban on interracial marriage, which the Supreme Court struck down in 1967. The states respond that they have always set the rules for marriage and that voters in many states have backed, sometimes overwhelmingly, changes to their constitutions to limit marriage to a man and a woman. They say a lively national debate is underway and there is no reason for courts to impose a solution that should be left to the political process. The states also argue that they have a good reason to keep defining marriage as they do. Because only heterosexual couples can produce children, it is in the states’ interest to make marriage laws that encourage those couples to enter a union that supports raising children. • • • Is the Obama administration playing a role? The administration is backing the right of same-sex couples to marry, although its argument differs in one respect. The plaintiffs say that the state laws should fall, no matter what standard the court applies. The administration calls for more rigorous scrutiny than courts ordinarily apply to most laws, saying it is appropriate when governments discriminate against a group of people. That already is the case for claims that laws discriminate on the basis of race, sex and other factors. But the administration is silent about what the outcome should be if the court does not give gays the special protection it has afforded women and minorities. The Justice Department’s decision to stop defending the federal anti-marriage law in 2011 was an important moment for gay rights and President Barack Obama declared his support for same-sex marriage in 2012. • • • What happens if the court strikes down the state bans? A ruling that same-sex couples have a right to marry would invalidate the remaining anti-gay marriage laws in the country. If the court limits its ruling to requiring states to recognize same-sex unions, couples in states without same-sex marriage presumably could get married elsewhere and then demand recognition at home. • • • What happens if the court rules for the states on both questions? The bans in 14 states would survive. Beyond that, confusion probably would reign. Some states that had their marriage laws struck down by federal courts might seek to reinstate prohibitions on gay and lesbian unions. Questions also could be raised about the validity of some same-sex weddings. Many of these problems would be of the Supreme Court’s own making. • • • Why is that? From October to January, the justices first rejected appeals from states seeking to preserve their marriage bans, then allowed court rulings to take effect even as other states appealed those decisions. The result is that the court essentially allowed the number of states with same-sex marriage to double. • • • Where is same-sex marriage legal? Same-sex couples can marry in 36 states, the District of Columbia and parts of Missouri. More than 500 marriage licenses were issued to same-sex couples in Alabama this year after a federal court struck down the state’s ban. But probate judges have not issued any more licenses to gay and lesbian couples since the Alabama Supreme Court ordered a halt to same-sex unions in early March. Gay and lesbian couples may not marry in Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, most of Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, Tennessee and Texas. • • • How many same-sex couples are there in the U.S.? Gary Gates, an expert at UCLA’s Williams Institute on the demography of gays and lesbians in the U.S., estimated that there were 350,000 married same-sex couples as of February. Gates relied on Gallup Inc. survey data and Census Bureau information to arrive at his estimate. That’s just 0.3 percent of the nation’s 242 million adults, Gates said.

Alabama gay marriage fight echoes states’ rights battles

Alabama Chief Justice Roy Moore‘s judicial building office overlooks Montgomery’s Dexter Avenue, a history-soaked thoroughfare topped by the Alabama Capitol where Jefferson Davis was inaugurated president of the Confederacy and where the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. ended the 1965 march for voting rights. As gay and lesbian couples left a nearby courthouse clutching marriage licenses last week, Moore, an outspoken critic of gay marriage, was fighting to stop the weddings using a states’ rights argument that conjured up those historical ghosts of slavery, the Civil War and the battle against desegregation. There has been resistance in other states to the tide of rulings allowing gay marriage. Some Florida clerks’ offices scrapped all marriage ceremonies rather than perform same-sex unions. In South Carolina and Georgia, legislation is being developed to let individual employees opt out of issuing marriage licenses to gay couples out of sincere religious belief. No state, however, went as far as Alabama, where the 68-year-old Moore instructed the state’s probate judges not to issue marriage licenses to gay couples. “It’s my duty to speak up when I see the jurisdiction of our courts being intruded by unlawful federal authority,” Moore said. Moore objected to a Jan. 23 ruling by U.S. District Judge Callie Granade in Mobile that Alabama’s gay marriage ban violates the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection and due process. After the Supreme Court on Feb. 9 refused to stay the decision, Alabama became the 37th state – plus the District of Columbia – where gays and lesbians can legally wed. In his dissent when the U.S. Supreme Court refused to block that order, Justice Clarence Thomas pointedly raised the states’ rights flag, complaining that the court’s decision was made “without any regard for the people who approved these laws in popular referendums or elected the representatives who voted for them.” The decision, he added, “represents yet another example of this court’s increasingly cavalier attitude toward the states.” Moore, who is head of the Alabama court system, threw the Granade ruling into disarray when he urged the probate judges in a letter to stand against “judicial tyranny” and claims Granade had no authority to “redefine marriage.” Alabama probate judges were not defendants in the case, Moore argues, and thus are not subject to a direct court order. He also said they are part of a parallel state court system that doesn’t have to submit to Granade’s views until the U.S. Supreme Court says otherwise. “She has no control over the state of Alabama to force all probate judges to do anything,” Moore said. “This is a case of dual sovereignty of federal and state authorities. The United States Supreme Court is very clear in recognizing that federal courts do not bind state courts.” Although he bristles at the link, Moore’s action drew inevitable parallels with former Gov. George Wallace’s 1963 “stand in the schoolhouse door” aimed at preventing federal court mandated desegregation at the University of Alabama. Wallace was attempting to fight integration nine years after education segregation was ruled illegal by the U.S. Supreme Court. Moore said such a final decision hasn’t happened yet on the subject of gay marriage. “The rhetoric and demagoguery of states’ rights and federal judges, you can’t help but make that comparison,” said Doug Jones, a former U.S. attorney who prosecuted the two Ku Klux Klansmen who bombed Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church in 1963, killing four black girls in a crime that helped galvanize the civil rights movement. Many legal experts think Moore and other states’ rights advocates are on shaky ground. Ruthann Robson, a law professor at the City University of New York, said Granade’s decision should be considered the law of the state unless overruled by a higher court or contradicted by a state court. “If what Moore says is true, then no federal court could ever hold a state law, regulation or policy unconstitutional. And the 14th Amendment, then, would be essentially meaningless,” Robson said in an email. It’s unclear what Moore’s reaction would be if the U.S. Supreme Court determines that gay marriage bans nationwide are unconstitutional when the justices issue their ruling later this year. But Robson pointed to a 1958 decision involving a school desegregation fight in Little Rock, Arkansas, that made it clear states must adhere to the high federal court’s interpretation of the Constitution – a cornerstone of the inherent authority the U.S. government has on constitutional issues over the states. “If parties defy a direct order, the remedy is contempt,” she said. An official found in contempt can be fined or even jailed. Alabama Gov. Robert Bentley, a Republican and Southern Baptist who reads his Bible every morning in his office, said he firmly believes marriage should be between one man and one woman. But he doesn’t want Alabama to go against history’s tide this time. “I have friends who obviously believe very strongly that defiance is the route to go. I just personally don’t feel that way and I have to be the governor of all the people. I have to represent the state of Alabama to the rest of the nation and the rest of the world,” Bentley said. In Florida, the law firm that advises the state’s 67 court clerks initially said a Tallahassee federal judge’s decision voiding a gay marriage ban only applied to one clerk. That’s because, the lawyers reasoned, only that clerk was specifically named in that case. Moore made a similar argument in saying his state’s probate judges were not specifically cited. In Tallahassee, U.S. District Judge Robert Hinkle responded by warning clerks choosing not to follow his ruling that they could face serious legal consequences in future lawsuits, including payment of costs and attorney’s fees. All the clerks eventually complied without incident in early January. “History records no shortage of instances when state officials defied federal court orders on issues of federal constitutional law,” Hinkle wrote in the New Year’s Day order. “Happily, there are many more instances when responsible

Gay couples wed in once-reluctant Alabama county

The federal judge who overturned Alabama’s gay-marriage ban ordered a reluctant county to begin issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples, signaling to probate judges across the state that they should do the same. About an hour after U.S. District Judge Callie Granade’s ruling, Mobile County opened up its marriage license office and started granting the documents to gay couples. Gay-rights advocates said they hoped Granade’s order would smooth an uneven legal landscape where gay couples have been able to marry in some Alabama counties and not in others. However, it wasn’t immediately clear what other judges would do. At least 23 of Alabama’s 67 counties are issuing marriage licenses to gay couples. Robert Povilat and his partner Milton Persinger were the first of several couples to get a marriage license in Mobile County. They wore camellia boutonnieres and exchanged vows in the atrium. “Ecstatic. Ecstatic. We’re married,” Povilat said. Randall Marshall, legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Alabama, said his group was ready to litigate the case county by county, if necessary. “We hope other probate judges will look at this and see they too could soon be a defendant in a lawsuit if they don’t start treating everybody equally,” Marshall said. Mobile and other counties had refused to issue the marriage licenses after Alabama Chief Justice Roy Moore told probate judges on Sunday they didn’t have to because they were not defendants in the original case. Moore has argued that Granade’s Jan. 23 ruling striking down the Bible Belt state’s gay-marriage ban was an illegal intrusion on Alabama’s sovereignty. Moore made a name for himself by fighting to keep a Ten Commandments monument at a courthouse, refusing to remove it even though a federal judge ordered him to. His resistance cost him his job, but he won re-election as chief justice in 2012. Moore was not at the brief hearing Granade held Thursday because he was . However, he was often the subject of the discussion. Marshall called Moore’s directive, sent hours before courthouses opened Monday, a “ploy” to stop gay marriage in Alabama. A telephone message left with Moore’s office was not immediately returned Thursday. Before the hearing, Moore was steadfast in his belief that the federal courts had intruded in the state’s sovereignty. “Once they start tampering with the definition of marriage which was given of God, there is no end to it,” he said. A long-time supporter of Moore’s, who watched the hearing, predicted that this would not be the end of the fight. Orange Beach businessman Dean Young dismissed the hearing as a “dog and pony show.” “Eighty-one percent of the people voted for a constitutional amendment saying marriage is between one man and one woman,” Young said of the 2006 vote for a gay marriage ban. Michael Druhan, an attorney for Mobile County Probate Judge Don Davis, said Davis closed marriage license operations altogether this week – even for heterosexual couples – rather than navigate what seemed like a legal minefield of conflicting directives. The number of states in which gay and lesbian couples can marry has nearly doubled since October, from 19 to 37, largely as a result of terse Supreme Court orders that allowed lower court rulings to become final and rejected state efforts to keep marriage bans in place pending appeals. The U.S. Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in April and is expected to issue a ruling by June regarding whether gay couples nationwide have a fundamental right to marry and whether states can ban such unions. Republished with permission of the Associated Press.