Local governments are spending billions of pandemic relief funds, but some report few specifics

Joplin officials say they have big plans for $13.8 million of pandemic relief funds the tornado-ravaged southwestern Missouri city received under a two-year-old federal law. Yet the latest federal records show none of the money has been spent — or even budgeted. In fact, about 6,300 cities and counties — nearly 1 in 4 nationwide — reported no expenditures as of this spring, according to an Associated Press analysis of data released by the U.S. Treasury Department. About 5,100 of those listed have no projects — either planned or underway. So what gives? Is the money not needed? Are cities just sitting on it? Local and federal officials told the AP in interviews that the publicly available data is misleading — pockmarked by differing interpretations over exactly what must be reported, lagging in timeliness, and failing to account for some preliminary planning. Critics contend it’s an indication of a flawed pandemic response. Federal officials estimate that governments have spending commitments for more than 80% of the funds, even if that’s hard to tell from their reporting requirements. Joplin, for example, plans to spend its pandemic aid on housing projects, high-speed internet, streets, a bicycle park, public safety equipment, and more. The City Council approved the plan last month. But it won’t show up on federal reports until October. The city, which was devastated in 2011 by one of deadliest tornadoes in U.S. history, took a deliberate approach with its pandemic aid to develop “really transformational projects,” said Leslie Haase, the city’s finance director. Over the past couple of years, it leveraged the pandemic aid to win millions of additional dollars of state grants. With the combined funds, it plans to relaunch an expired post-tornado program that helps people make down payments on homes. The city also plans to spend millions of dollars to repair or demolish old houses. “I think by the time 2026 rolls around, Joplin will be a better community,” Haase said. The $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan — passed in 2021 by a Democratic-led Congress and signed by President Joe Biden — contained $350 billion of flexible aid to states, territories, tribes, counties, cities, and towns. The Biden administration says the money was intended to provide both immediate aid amid a health crisis and a longer-term boost for communities. Governments must obligate that money for projects by the end of next year and spend it by the close of 2026. As of their April reports, more than 26,500 governments collectively had spent 43% of their funds and approved plans for spending 77% of the money, according to the AP’s analysis. The actual amount of spending commitments likely is well over 80% when accounting for lag times and different reporting approaches taken by local governments, said Gene Sperling, the White House American Rescue Plan coordinator “What you see across the country is that counties, cities, states overwhelmingly have committed these funds, are using them, are on track to meet their legal deadlines to have all the funds obligated by the end of 2024,” Sperling said. But Republicans and fiscal conservatives have questioned whether the spending is necessary, noting that most states rebounded quickly from an initial tax plunge during the pandemic to post large budget surpluses. “Although the Left claimed their $2 trillion bill was designed to fight COVID, they wasted hundreds of billions of Americans’ hard-earned tax dollars on ridiculous things,” Republican U.S. Rep. Jason Smith, chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, said in a statement to the AP. Among other things, the money helped finance an upscale hotel in Florida, a minor league baseball stadium in New York, and prisons in Alabama — drawing outrage from some members of Congress. Some governments waited to do anything with the money until the Treasury Department finalized its rules in April 2022. Details are lacking on how some governments are using their funds because the Treasury relaxed reporting requirements for any money categorized by state or local officials as a replacement for lost revenues. According to the AP’s analysis, more than 6,000 local governments categorized their entire federal allotment as “revenue replacement” — often taking advantage of a Treasury rule that allows up to $10 million of assumed revenue loss without having to prove it. Though they can provide more details if they choose, governments categorizing all their federal aid as replacement revenue only have to report it as one project, the Treasury told the AP. But some didn’t even do that. The Denver suburb of Lakewood, Colorado, claimed its entire $21.6 million allotment as a revenue replacement since it had dipped into reserves to pay police during the pandemic. It reported no projects. Yet the federal aid helped the city to construct sidewalks, replace computer software, upgrade the police radio system, and make fire and safety improvements to a civic center, among other things, said Lakewood Chief Financial Officer Holly Bjorklund. Those were “essential things that really needed to be done and would cost more if we waited longer to address them,” she said. Maryland’s capital city of Annapolis also described no projects in its April report. But Annapolis already has used $1.2 million of its $7.6 million allotment as a revenue replacement for its depleted public transit funds, said city spokesperson Mitchelle Stephenson. It expects to tap more of the federal aid for city operations in the 2024 budget. The Treasury’s guidance about how to report revenue replacement funds used for government services wasn’t very clear, said Katie Buckley, federal funding assistance program director for the Vermont League of Cities and Towns. But Buckley said she advised local officials to report it all as one project for government services, and then list what that included. Counting the federal money as replacement funding for government services shouldn’t relieve local officials of describing what they did with it — even if it just went toward salaries or office supplies, said Sean Moulton, senior policy analyst at the nonprofit Project on Government Oversight. “This is taxpayer money and a lot of it,” said Moulton,

States and cities slow to spend federal pandemic money

As Congress considered a massive COVID-19 relief package earlier this year, hundreds of mayors from across the U.S. pleaded for “immediate action” on billions of dollars targeted to shore up their finances and revive their communities. Now that they’ve received it, local officials are taking their time before actually spending the windfall. As of this summer, a majority of large cities and states hadn’t spent a penny from the American Rescue Plan championed by Democrats and President Joe Biden, according to an Associated Press review of the first financial reports due under the law. States had spent just 2.5% of their initial allotment while large cities spent 8.5%, according to the AP analysis. Many state and local governments reported they were still working on plans for their share of the $350 billion, which can be spent on a wide array of programs. Though Biden signed the law in March, the Treasury Department didn’t release the money and spending guidelines until May. By then, some state legislatures already had wrapped up their budget work for the next year, leaving governors with no authority to spend the new money. Some states waited several more months to ask the federal government for their share. Cities sometimes delayed decisions while soliciting suggestions from the public. And some government officials — still trying to figure out how to spend previous rounds of federal pandemic aid — simply didn’t see an urgent need for the additional cash. “It’s a lot of money that’s been put out there. I think it’s a good sign that it hasn’t been frivolously spent,” Louisville Mayor Greg Fischer said. He was president of the U.S. Conference of Mayors when more than 400 mayors signed a letter urging Congress to quickly pass Biden’s plan. The law gives states until the end of 2024 to make spending commitments and the end of 2026 to spend the money. Any money not obligated or spent by those dates must be returned to the federal government. The Biden administration said it isn’t concerned about the early pace of the initiative. The aid to governments is intended both “to address any crisis needs” and to provide “longer-term firepower to ensure a durable and equitable recovery,” said Gene Sperling, White House American Rescue Plan coordinator. “The fact that you can spread your spending out is a feature, not a bug, of the program. It is by design,” Sperling told the AP. The Treasury Department set an aggressive reporting schedule to try to prod local planning. It required states, counties, and cities with estimated populations of at least 250,000 to file reports by Aug. 31 detailing their spending as of the previous month as well as future plans. More than half the states and nearly two-thirds of the roughly 90 largest cities reported no initial spending. The governments reported future plans for about 40% of their total funds. The AP did not gather reports from counties because of the large number of them. To promote transparency, the Treasury Department also required governments to post the reports on a “prominent public-facing website,” such as their home page or a general coronavirus response site. But the AP found that many governments ignored that directive, instead tucking the documents behind numerous navigational steps. Idaho and Nebraska had not posted their reports online when contacted by the AP. Neither had some cities. Officials in Jersey City, New Jersey, required the AP to file a formal open-records request to get its report, though that shouldn’t have been necessary. City employees in Laredo, Texas, and Sacramento, California, also initially directed the AP to file open-records requests. Laredo later told the AP it had spent nothing. Sacramento relented and eventually provided a short report stating it had spent nothing but might put its entire $112 million allocation toward replacing lost revenue and providing government services. Among states, the largest share of initial spending went toward shoring up unemployment insurance trust funds that were depleted during the pandemic. Arizona reported pouring nearly $759 million into its unemployment account, New Mexico nearly $657 million, and Kentucky almost $506 million. For large cities, the most common use of the money was to replenish their diminished revenue and fund government services. San Francisco reported using its entire initial allotment of $312 million for that purpose. Those reporting no initial spending included Pittsburgh, whose mayor joined with several other Pennsylvania mayors in February on a column urging Congress to pass “crucial” aid for state and local governments. “Congress must act, and they must act soon. Our communities cannot wait another day,” the Pennsylvania mayors wrote. Pittsburgh ultimately ended up waiting to spend the money until the Treasury guidelines were released, community members had a chance to comment and the City Council could sign off on the spending plans. In the future, the city plans to use part of its federal windfall to buy 78 electric vehicles, build technology labs at recreation centers and launch a pilot project paying 100 low-income Black women $500 a month for two years to test the merits of a guaranteed income program. The federal money also will help pay the salaries of more than 600 city employees “Even though the money hadn’t technically been expended” by the Treasury Department’s reporting timeline, “the receipt of the money was enough for us to hold off on major layoffs,” said Dan Gilman, chief of staff to Pittsburgh Mayor William Peduto. Some officials are intentionally taking their time. Missouri Gov. Mike Parson, a Republican, opted not to call a special session to appropriate money from the latest federal pandemic relief act. So far, he’s publicly outlined just one proposal — $400 million for broadband. Parson’s budget director said the administration will present more ideas to lawmakers when they convene for their regular session in January. Until then, the state should have enough money left from a previous federal relief law to cover the costs of fighting the virus, budget director Dan Haug said. “We want to try to find

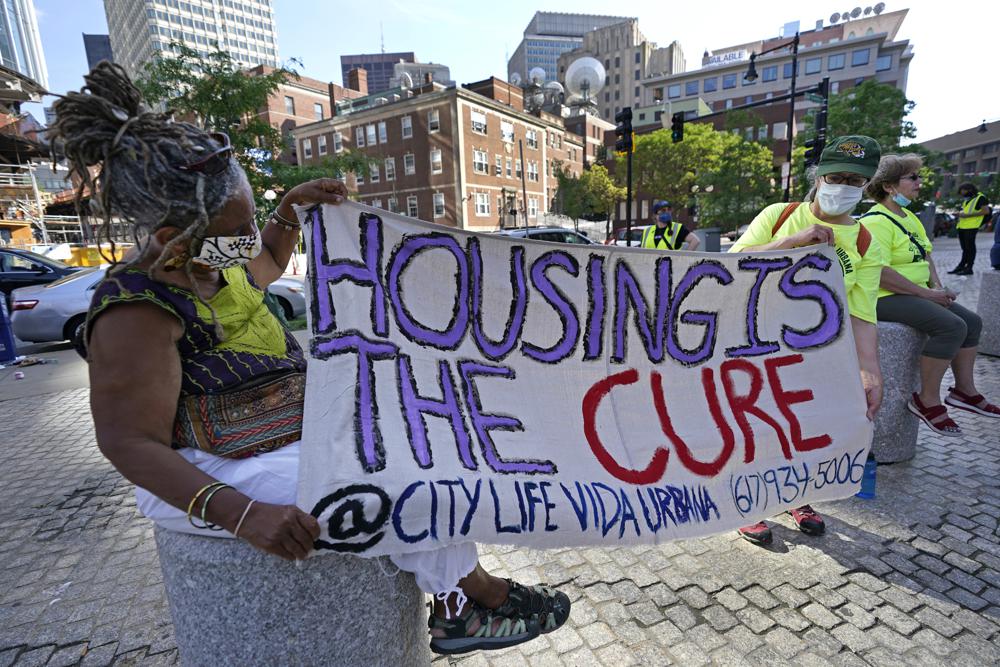

Joe Biden to allow eviction moratorium to expire Saturday

The Biden administration announced Thursday it will allow a nationwide ban on evictions to expire Saturday, arguing that its hands are tied after the Supreme Court signaled the moratorium would only be extended until the end of the month. The White House said President Joe Biden would have liked to extend the federal eviction moratorium due to spread of the highly contagious delta variant of the coronavirus. Instead, Biden called on “Congress to extend the eviction moratorium to protect such vulnerable renters and their families without delay.” “Given the recent spread of the delta variant, including among those Americans both most likely to face evictions and lacking vaccinations, President Biden would have strongly supported a decision by the CDC to further extend this eviction moratorium to protect renters at this moment of heightened vulnerability,” the White House said in a statement. “Unfortunately, the Supreme Court has made clear that this option is no longer available.” Aides to Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and Sen. Sherrod Brown, the chairman of the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, said the two are working on legislation to extend the moratorium. Democrats will try to pass a bill as soon as possible and are urging Republicans not to block it. In the House, a bill was introduced Thursday to extended the moratorium until the end of the year. But the prospect of a legislative solution remained unclear. The court mustered a bare 5-4 majority last month, to allow the eviction ban to continue through the end of July. One of those in the majority, Justice Brett Kavanaugh, made clear he would block any additional extensions unless there was “clear and specific congressional authorization.” By the end of March, 6.4 million American households were behind on their rent, according to the Department of Housing and Urban Development. As of July 5, roughly 3.6 million people in the U.S. said they faced eviction in the next two months, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey. Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in June this would be the last time the moratorium would be extended when she set the deadline for July 31. It was initially put in place to prevent further spread of COVID-19 by people put out on the streets and into shelters. Housing advocates and some lawmakers have called for the moratorium to be extended due to the increase in coronavirus cases and the fact so little rental assistance has been distributed. Congress has allocated nearly $47 billion in assistance that is supposed to go to help tenants pay off months of back rent. But so far, only about $3 billion of the first tranche of $25 billion has been distributed through June by states and localities. Some states like New York have distributed almost nothing, while several have only approved a few million dollars. “The confluence of the surging delta variant with 6.5 million families behind on rent and at risk of eviction when the moratorium expires demands immediate action,” said Diane Yentel, executive director of the National Low Income Housing Coalition. “The public health necessity of extended protections for renters is obvious. If federal court cases made a broad extension impossible, the Biden administration should implement all possible alternatives, including a more limited moratorium on federally backed properties.” Gene Sperling, who is charged with overseeing the implementation of Biden’s $1.9 trillion coronavirus rescue package, said it was key that states and local authorities speed up the rental assistance distribution. “The message is that there are no excuses,” he told The Associated Press. “States and cities across the country have shown these programs can work, that they can get money out the door effectively and efficiently,” he continued. “The fact that some states and cities are showing they can do this efficiently and effectively makes clear that there is no reason that every state and city shouldn’t be accelerating their funds to landlords and tenants, particularly in light of the end of the CDC eviction moratorium.” The trouble getting rental assistance to those who need it has prompted the Biden administration to hold several events in the past month aimed at pressuring states and cities to increase their distribution, coax landlords to participate, and make it easier for tenants to get money directly. Associate Attorney General Vanita Gupta also has released an open letter to state courts around the country encouraging them to pursue measures that would keep eviction cases out of the courts. On Wednesday, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau unveiled a tool that allows tenants to find information about rental assistance in their area. Despite these efforts, some Democratic lawmakers had demanded the administration extend the moratorium. “This pandemic is not behind us, and our federal housing policies should reflect that stark reality. With the United States facing the most severe eviction crisis in its history, our local and state governments still need more time to distribute critical rental assistance to help keep a roof over the heads of our constituents,” Democratic U.S. Reps. Cori Bush of Missouri, Jimmy Gomez of California, and Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts said in a joint statement. But landlords, who have opposed the moratorium and challenged it repeatedly in court, were against any extension. They have argued the focus should be on speeding up the distribution of rental assistance. This week, the National Apartment Association and several others this week filed a federal lawsuit asking for $26 billion in damages due to the impact of the moratorium. “Any extension of the eviction moratorium equates to an unfunded government mandate that forces housing providers to deliver a costly service without compensation and saddles renters with insurmountable debt,” association president and CEO Bob Pinnegar said, adding that the current crisis highlights the need for more affordable housing. “Our nation faces an alarming housing affordability disaster on the horizon — it’s past time for the government to enact responsible and sustainable solutions that ultimately prioritize making both

Kamala Harris, Jill Biden on the road to promote aid plan

From a vaccination site in the desert West to a grade school on the Eastern seaboard, President Joe Biden’s top messengers — his vice president and wife among them — led a cross-country effort Monday to highlight the benefits of his huge COVID relief plan. Biden, Vice President Kamala Harris, and their spouses have launched an ambitious tour this week to promote the $1.9 trillion plan as a way to battle the pandemic and boost the economy. The roadshow — dubbed the “Help is here” tour by the White House — began with Harris visiting a COVID-19 vaccination site and a culinary academy in Las Vegas and first lady Jill Biden touring a New Jersey elementary school. Biden himself heads out Tuesday. “We want to avoid a situation where people are unaware of what they’re entitled to,” Harris said at the culinary academy. “It’s not selling it; it literally is letting people know their rights. Think of it more as a public education campaign.” The White House is wasting no time promoting the relief plan, which Biden signed into law last week, looking to build momentum for the rest of his agenda and anxious to avoid the mistakes of 2009 in boosting that year’s recovery effort. Even veterans of Barack Obama’s administration acknowledge they did not do enough then to showcase their massive economic stimulus package. Biden stayed back in Washington for a day, declaring that “hope is here in real and tangible ways.” He said the new government spending will bankroll efforts that could allow the nation to emerge from the pandemic’s twin crises, health and economic. “Shots in arms and money in pockets,” Biden said at the White House. “That’s important. The American Rescue Plan is already doing what it was designed to do: make a difference in people’s everyday lives. We’re just getting started.” Biden said that within the next 10 days, his administration will clear two important benchmarks: distributing 100 million stimulus payments and administering 100 million vaccine doses since he took office. To commemorate those milestones, Biden and his top representatives are embarking on their most ambitious travel schedule of his young presidency, visiting a series of potential election battleground states this week. The sales pitch was leaving Republicans cold. Senate GOP leader Mitch McConnell dismissed the target of doses that Biden set when he took office as “not some audacious goal” but just the pace that he inherited. And he mocked Biden’s talk of Americans working toward merely being able to gather in small groups by July 4th as “bizarre.” The Biden plan cleared Congress without any backing from Republicans, despite polling that found broad public support. Republicans argued the bill was too expensive, especially with vaccinations making progress against the virus, and included too many provisions not directly linked to the pandemic. After beginning the sales campaign with high-profile speeches, Biden will head to Pennsylvania on Tuesday and then join Harris in Georgia on Friday. Others on his team are visiting the electorally important states of Nevada, Colorado, New Mexico, and New Hampshire. The trip Monday marked Harris’ first official journey in office and included an unscheduled stop at a vegan taco stand as well as a coffee stand at the Culinary Academy Las Vegas. White House press secretary Jen Psaki said, “We want to take some time to engage directly with the American people and make sure they understand the benefits of the package and how it is going to help them get through this difficult period of time.” The White House has detailed a theme for each day, focusing on small businesses, schools, home evictions and direct checks to most Americans. Jill Biden was joined by New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy on a tour Monday of Samuel Smith Elementary School in Burlington, where she highlighted steps the school took to reopen. But her tour revealed the challenges ahead: In one classroom she visited, only two students were in attendance for in-person learning while the other 17 were virtual. The first lady sat down at a computer to say hello to the remote learners. “I just I love being here at a school again: Educators, parents and students, the entire school has come together to bring kids back to the classroom,” she said. “But even with your best efforts, students can’t come, they can’t come in every day, which means that their parents are still having to take time off of work or figure out childcare solutions. And this school, like schools across this country, can’t fully reopen without help.” The president on Monday also announced that he had chosen Gene Sperling, a longtime Democratic economic policy expert, to oversee the massive stimulus package, the role Biden himself had played for the 2009 economic rescue package. The goal, Biden said, is to “stay on top of every dollar spent.” “I learned from my experience implementing the Recovery Act just how important it is to have someone who can manage all the moving parts with efficiency, speed and integrity, and accountability,” said the president. The plan’s key features include direct payments of $1,400 for most single taxpayers, or $2,800 for married couples filing jointly, plus $1,400 per dependent — a total of $5,600 for a married couple with two children. The payments phase out for people with higher incomes. An extension of federal unemployment benefits will continue through Sept. 6 at $300 a week. There’s $350 billion for state, local and tribal governments, $130 billion for K-12 schools, and about $50 billion to expand COVID-19 testing, among other provisions. Restaurants and bars that were forced to close or limit service can take advantage of a new multibillion-dollar grant program, and the plan also has tens of billions of dollars to help people who have fallen behind on rent and mortgage payments. Harris’ husband, Doug Emhoff, joined his wife for the Western trip, visiting a food relief organization Monday in Las Vegas and participating in a listening session with the organization’s partners. In

Democrats to ‘act big’ on $1.9T aid; GOP wants plan split

Democrats in Congress and the White House rejected a Republican pitch to split President Joe Biden’s $1.9 trillion COVID-19 rescue plan into smaller chunks on Thursday, with lawmakers appearing primed to muscle the sweeping economic and virus aid forward without GOP help. Despite Biden’s calls for unity, Democrats said the stubbornly high unemployment numbers and battered U.S. economy leave them unwilling to waste time courting Republican support that might not materialize. They also don’t want to curb the size and scope of a package that they say will provide desperately needed money to distribute the vaccine, reopen schools and send cash to American households and businesses. Biden has been appealing directly to Republican and Democratic lawmakers while signaling his priority to press ahead. “We’ve got a lot to do, and the first thing we’ve got to do is get this COVID package passed,” Biden said Thursday in the Oval Office. The standoff over Biden’s first legislative priority is turning the new rescue plan into a political test — of his new administration, of Democratic control of Congress and of the role of Republicans in a post-Trump political landscape. Success would give Biden a signature accomplishment in his first 100 days in office, unleashing $400 billion to expand vaccinations and to reopen schools, $1,400 direct payments to households, and other priorities, including a gradual increase in the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour. Failure would be a high-profile setback early in his presidency. Democrats in the House and Senate are operating as though they know they are borrowed time. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi are laying the groundwork to start the go-it-alone approach as soon as next week. They are drafting a budget reconciliation bill that would start the process to pass the relief package with a simple 51-vote Senate majority — rather than the 60-vote threshold typically needed in the Senate to advance legislation. The goal would be passage by March, when jobless benefits, housing assistance and other aid is set to expire. Schumer said he drew from Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s advice to “act big” to weather the COVID-19 economic crisis. “Everywhere you look, alarm bells are ringing,” Schumer said from the Senate floor. Senate Republicans in a bipartisan group warned their colleagues in a “frank” conversation late Wednesday that Biden and Democrats are making a mistake by loading up the aid bill with other priorities and jamming it through Congress without their support, according to a person familiar with the matter who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss the private session. Sen. Rob Portman, R-Ohio, a former White House budget director under George W. Bush, wants a deeper accounting of what funds remain from the $900 billion coronavirus aid package from December. “Literally, the money has not gone out the door,” he said. “I’m not sure I understand why there’s a grave emergency right now.” Biden spoke directly with Republican Sen. Susan Collins of Maine, who is leading the bipartisan effort with Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., that is racing to strike a compromise. Collins said she and the president had a “good conversation.” “We both expressed our shared belief that it is possible for the Senate to work in a bipartisan way to get things done for the people of this country,” she said. The emerging debate is highly reminiscent of the partisan divide over the 2009 financial rescue in the early months of the Obama administration, when Biden was vice president, echoing those battles over the appropriate level of government intervention. White House press secretary Jen Psaki said that although Biden wants a bipartisan package, the administration is opposed to breaking it up to win Republican support. “We’re open for business and open to hear from members of Congress on that,” she said, noting that lawmakers are not “wallflowers.” But, she said, “We’re not going to do this in a piecemeal way or break apart a big package that’s meant to address the crisis we’re facing.” On Thursday, more than 120 economists and policymakers signed a letter in support of Biden’s package, saying the $900 billion that Congress approved in December before he took office was “too little and too late to address the enormity of the deteriorating situation.” Employers shed workers in December, retail sales have slumped and COVID-19 deaths kept rising. More than 430,000 people in the U.S. have died from the coronavirus as of Thursday. At the same time, the number of Americans applying for unemployment benefits remained at a historically high 847,000 last week, and a new report said the U.S. economy shrunk by an alarming 3.5% last year. “The risks of going too small dramatically outweigh the risks of going too big,” said Gene Sperling, a former director of the White House National Economic Council, who signed the letter. The government reported Thursday that the economy showed dangerous signs of stalling in the final three months of last year, ultimately shrinking in size by 3.5% for the whole of 2020 — the sharpest downturn since the demobilization that followed the end of World War II. The decline was not as severe as initially feared, largely because the government has steered roughly $4 trillion in aid, an unprecedented emergency expenditure, to keep millions of Americans housed, fed, employed, and able to pay down debt and build savings amid the crisis. Republican allies touted the 4% annualized growth during the last quarter, with economic analyst Stephen Moore calling the gains “amazing.” Republicans have also raised concerns about adding to the deficit, which skyrocketed in the Trump administration. Republican Sen. John Barrasso of Wyoming, the third-ranking party leader, said Biden should stick to the call for unity he outlined in his inaugural address, particularly with the evenly split Senate. “If there’s ever been a mandate to move to the middle, it’s this,” he said. “It’s not let’s just go off the cliff.” But Democrats argue that low interest rates make the debt manageable and that the possibility of returning to work will do more to improve people’s well-being.

Archives show Hillary Clinton OK’d tax breaks for nonprofits

As first lady in the final year of the Clinton administration, Hillary Rodham Clinton endorsed a White House plan to give tax breaks to private foundations and wealthy charity donors at the same time the William J. Clinton Foundation was soliciting donations for her husband’s presidential library, recently released Clinton-era documents show. The blurred lines between the tax reductions proposed by the Clinton administration in 2000 and the Clinton Library’s fundraising were an early foreshadowing of the potential ethics concerns that have flared around the Clintons’ courting of corporate and foreign donors for their family charity before she launched her campaign for the 2016 Democratic presidential nomination. White House documents in the Clinton Library reviewed by The Associated Press show Hillary Clinton and Bill Clinton were kept apprised about a tax reduction package that would have benefited donors, including those to his presidential library, by reducing their tax burden. An interagency task force set up by Bill Clinton’s executive order proposed those breaks along with deductions to middle-class taxpayers who did not itemize their returns. Federal officials estimated the plan would cost the U.S. government $14 billion in lost tax payments over a decade. In a January 2000 memo to Hillary Clinton from senior aides, plans for a “philanthropy tax initiative roll-out” showed her scrawled approval, “HRC” and “OK.” The document, marked with the archive stamp “HRC handwriting,” indicated her endorsement of the tax package, which included provisions to reduce and simplify an excise tax on private foundations’ investments and allow more deductions for charitable donations of appreciated property. The Clinton White House included the tax proposal in its final budget in February 2000, but it did not survive the Republican-led Congress. “Without your leadership, none of these proposals would have been included in the tax package,” three aides wrote to Hillary Clinton in the memo, days before she led a private conference call outlining the plan to private foundation and nonprofit leaders. Federal law does not prevent fundraising by a presidential library during a president’s term. While most modern-day presidents held off until the end of their term, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush allowed supporters to solicit donations while they were still in office, and President Barack Obama is now doing the same. But in directly pushing the legislation while the Clinton Library was aggressively seeking donations, Hillary and Bill Clinton’s altruistic support for philanthropy overlapped with their interests promoting their White House years and knitting ties with philanthropic leaders. Hundreds of pages of documents contain no evidence that anyone in the Clinton administration raised warnings about potential ethics concerns or sought to minimize the White House’s active role in the legislation. “The theme here for the Clintons is a characteristic ambiguity of doing good and at the same time doing well by themselves,” said Lawrence Jacobs, director of the Center for the Study of Politics and Governance at the Hubert H. Humphrey School at the University of Minnesota. Jacobs said the Clinton administration could have relied on a federal commission to decide tax plans or publicly supported changes but not specific legislation. Instead, Jacobs said, “this was a commitment by the Clinton White House to identify options and promote them with no regard to the larger picture.” Spokesmen for Hillary Clinton’s campaign and the Clinton Foundation declined to comment, deferring to the former president’s office. A spokesman for Bill Clinton’s office said that his administration was not trying to incentivize giving to the foundation, but instead was spurred by a 1997 presidential humanities committee that urged tax breaks for charities to aid American cultural institutions. Bruce Reed, Bill Clinton’s chief domestic policy adviser at the time, also responded Thursday that the former president “wanted to give a break to working people for putting a few more dollars in the plate at the church. Not for any other far-fetched reason.” Gene Sperling, former economic adviser to both Bill Clinton and President Obama, added that the tax reduction package was “developed at the Treasury Department, endorsed by experts and designed to encourage all forms of charitable giving.” The Clinton Foundation would not have benefited directly by the tax proposals. The foundation is a public charity and not subject to the excise tax, which applies only to private foundations and is still law. The foundation is also not known to donate appreciated property and stocks to other charities. But the tax changes would have indirectly helped the foundation — as well as many other U.S. charities — by freeing nonprofits’ investments and donations that otherwise would have gone into tax payments. A reduction of the excise tax would have boosted the assets of private foundations. Higher deductions for appreciated investments and property would have also aided the Clinton Foundation, which accepts noncash gifts. In 2010, for example, the charity declared more than $5 million in donated securities on its federal tax returns. By the time the Clinton administration introduced its tax package in February 2000, the foundation had already raised $6 million in donations, according to tax disclosures. Among corporate-tied nonprofits that pledged or donated at least $1 million to the library project through the early 2000s, according to tax documents and published reports, were the Wasserman Foundation, the Roy and Christine Sturgis Foundation, the Walton Family Foundation and the Anheuser-Busch Foundation. Though Bill Clinton did not take over the nonprofit until after his presidency, he had openly discussed his plans for the organization’s future with New York executives in June 1999. And the foundation’s fundraising was led at the time by a trusted childhood friend, James “Skip” Rutherford, now dean of the Clinton School of Public Service at the University of Arkansas. Rutherford said he was not aware of the tax proposals and was focused at the time on small donors and likely contributors across Arkansas. Months before proposing the tax breaks, Clinton White House officials began courting leaders from some of the nation’s most influential charities. In the summer of 1999, aides began discussing the