Jac VerSteeg: Poll accuracy might be worse than you thought

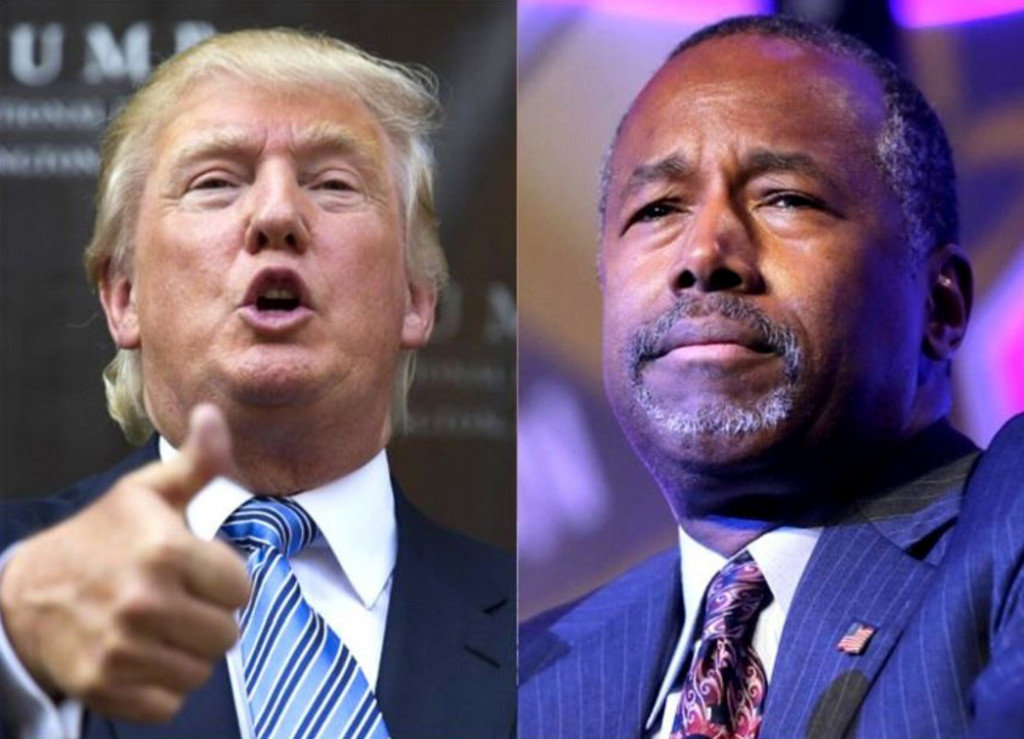

Way back in 1984, the late, great Chicago newspaperman Mike Royko wrote a column in which he urged readers to lie to pollsters. “Be polite. Talk to them,” Royko coached. “But lie. Don’t give them an honest answer.” Royko wrote that pollsters would collect the results and “feed them into a computer, which will chew on them, digest them and finally burp a sheet of paper” allowing the network’s “high priest of politics” to project the winner. “But if enough of you lie,” Royko encouraged, “the entire nation will be treated to one of the finest evenings of television viewing since the tube was unleashed.” Here we are more than 30 years later and it is becoming increasingly clear that people don’t need to lie to pollsters to screw up the results. Because of changes in the way human beings communicate – and I’m talking here primarily about smart phones – it might be impossible to conduct a valid poll. In which case the pollsters, some completely unwittingly, are lying to us. Certainly there have been a lot of incorrect predictions recently. Results in Kentucky, where pollsters overwhelmingly and erroneously predicted a Democrat would be the next governor, are just the latest high-profile example. Bob Sparks explained in his recent column for Context Florida that poor methodology can be partly to blame. And Sparks cited an analysis by Steve Vancore, also for Context Florida, that bolstered the point. Both of those columns are must reading for anyone trying to figure out how two polls – each supposedly the result of scientific research – can come to different conclusions or get election results so wrong. And polls do often disagree. As reported in the Nov. 8 South Florida Sun Sentinel, the NBC News/Wall Street Journal survey of Republican voters found Ben Carson on top with 29 percent to Donald Trump’s 23 percent, while the Quinnipiac University poll put Donald Trump on top with 24 percent and Ben Carson second with 23 percent. The discrepancy might be a simple matter of timing. Those two polls overlapped slightly on the calendar but were not conducted on identical days. They also differed in sample size, which slightly affects the margin of error. However, voices are emerging from the world of polling that sound a more serious alarm. In a story in September, Bloomberg News reported that “doubts are intensifying (about the accuracy of polling) after a series of high-profile misfires around the world in the past year, notably in Greece, Israel and Britain.” The key problem – which some also blame for the flawed polling that convinced Mitt Romney he would defeat Barack Obama in 2012 – is a decline in participation traced to the rise of cell phones. People increasingly do not have land lines and do not answer their cell phones unless they recognize the caller. Even then, they are as likely to text as call. Or they could be at the mall or the grocery store and decline to talk. Further, mobile phones are, well, mobile, which could have an effect on local or regional polling. In my own family, three people whose phone numbers have Florida area codes no longer reside in the Sunshine State. The Bloomberg piece quotes Kirby Goidel, editor of “Political Polling in the Digital Age”: “There isn’t a pollster out there who thinks about this seriously who isn’t a little bit uneasy.” Bloomberg is far from the only source reporting the concern. U.S. News & World Report, in a story from September, quotes Geoffrey Skelley of the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics: “The science of public surveying is in something of a crisis right now.” All the uncertainty leads to the inevitable questions. Are Trump’s and Carson’s numbers really that good? Are Jeb Bush’s numbers really that bad? There is no definitive answer since political polls, by their very nature, cannot be tested until there is an actual election. Even when we get to the caucuses and primaries – starting in early February of next year – we never will know whether the polls from this fall were correct. Because polling is “in crisis,” 2016’s elections will be the most important test for polling since public opinion surveys began. Not only will voters decide which candidates will hold office, they will learn which polling firms to trust – if any. In the meantime, when considering polls, remember that they might reflect built-in lies that make Royko’s suggestion seem quaint. Jac Wilder VerSteeg is a columnist for The South Florida Sun Sentinel, former deputy editorial page editor for The Palm Beach Post and former editor of Context Florida.

2016 presidential election predictions we can already make

In the past few decades, swing states, once major wild cards in presidential politics are becoming scarcer. When Florida decided the 2000 election with 537 votes, 12 states helped elect the president by less than five percentage points. In 2012, the number of swing states dropped to four. For today’s Electoral College, 40 of 50 states have voted for the same party in all four elections since 2000, writes Larry Sabato, Kyle Kondik and Geoffrey Skelley in today’s POLITICO. Of the 10 exceptions, three were flukes: New Mexico’s vote was “razor-thin” in going for Al Gore in 2000 Al Gore, as well as 2004 when George W. Bush won the state. Indiana and North Carolina were trending Democratic, narrowly electing Barack Obama in 2008, mostly because of a strong field game and advertising by Obama’s campaign. Hoosiers tend to be Republican, as do the Tar Heels, by a slight margin. Sabato estimates seven real swing states: Colorado, Florida, Nevada, Ohio, and Virginia – each backing Bush and Obama twice. Iowa and New Hampshire went Democratic in three of the past four presidential contests. It should them come as little surprise that the particular seven states start as the clear toss-ups on the first Electoral Map for 2016. Sabato writes: It’s effectively the same map we featured for much of the 2012 cycle, and it unmistakably suggests the Democratic nominee should start the election as at least a marginal Electoral College favorite over his or (probably) her Republican rival. However, at the starting gate it is wiser to argue that the next election is basically a 50-50 proposition. How can that be when Democrats are so much closer to the magic number of 270 than Republicans? At heart, it’s because the past is often not a good guide to the future. With regularity in modern history, the Electoral College’s alleged lock for one party has been picked by the other party, usually at eight-year intervals. A few states that appear to be solidly in one party’s column can switch in any given year because of short-term (Indiana) or long-term (Virginia) forces. Other states that merely lean to one party require less of a push to change allegiances. North Carolina tilts to the GOP and Wisconsin to the Democrats, but it doesn’t require much imagination to foresee the winning party flipping one or the other. To win in 2016, all Democrats have to do is hold off GOP gains and limit any blue-to-red transformations. If those state that Sabato sees as lean, likely, and safe Democratic, the nominee needs just 23 of the 85 toss-up electoral ballots. In addition, in the case a lean Democratic state such as Wisconsin falls to the Republicans, those lost votes can be easily made up with a handful of toss-ups. For Republicans, Sabato says winning poses a considerably greater challenge. First, he or she must hold all the usual R states, plus patching together another 64 electoral votes, or 79 votes if North Carolina goes Democrat. To do so, a GOP candidate would have to sweep of a handful of swing states – an unlikely scenario, unless a few election cycle essentials turn against Democrats — Obama’s job approval, the economy, war and the like. At this point in the election cycle, we can already make two predictions: Republicans will not win if they lose either Florida or Ohio. Although the two states are somewhat slightly more Republican than the U.S. as a whole, if the GOP wants any chance if success, they will pick a nominee appealing to both Sunshine and Buckeye State voters. Second, a Democratic path to the White House might be possible without Virginia, but anything more than a percent or two (either way) will be a definite failure. Virginia was slightly more Democratic than the nation in 2012, Sabato notes, for the first time since FDR, and there are rising population trends more favorable to Democrats. “If you plan to go where the action will be,” he concludes, “you can already safely book those autumn 2016 travel packages to Columbus, Denver, Des Moines, Las Vegas, Manchester, Richmond and Tampa.”