Only 7 democrats will be on the stage for the last presidential debate of 2019

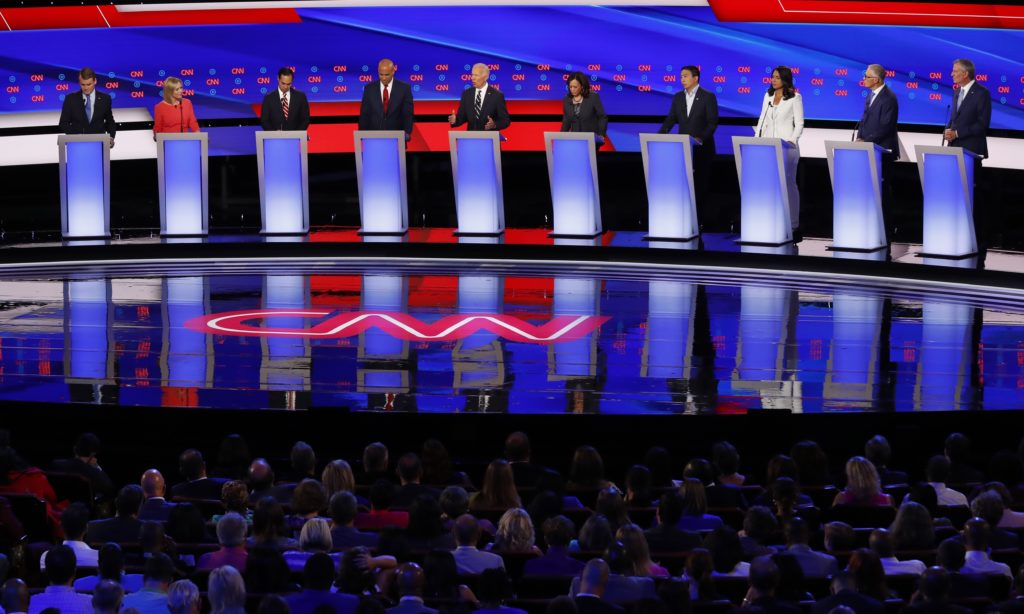

A winnowed field of Democratic presidential contenders takes the debate stage for a sixth and final time in 2019, as candidates seek to convince anxious voters that they are the party’s best hope to deny President Donald Trump a second term next year. Thursday night’s televised contest ahead of Christmas will bring seven rivals to heavily Democratic California, the biggest prize in the primary season and home to 1 in 8 Americans. And, coming a day after a politically divided House impeached the Republican president, the debate will underscore the paramount concern for Democratic voters: Who can beat Trump in November? With voters distracted by the holidays and the impeachment proceedings in Washington, the debate in Los Angeles could turn out to be the least watched so far. Viewership has declined in each round though five debates, and even campaigns have grumbled that the candidates would rather be on the ground in early voting states than again taking the debate stage. The lack of a clear front-runner reflects the uncertainty gripping many voters. Would Trump be more vulnerable to a challenge from the party’s liberal wing or a candidate tethered to the centrist establishment? Should the pick be a man or a woman, or a person of color? The Democratic field is also marked by wide differences in age, geography and wealth, and the party remains divided over issues including health care and the influence of big-dollar fundraising. There will be a notable lack of diversity onstage compared to earlier debates. For the first time this cycle, the debate won’t feature a black or Latino candidate. The race in California has largely mirrored national trends, with former Vice President Joe Biden, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders and Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren clustered at the top of the field, followed by South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg, Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar, businessman Andrew Yang and billionaire philanthropist Tom Steyer. Conspicuously missing from the lineup at Loyola Marymount University on Thursday will be former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, a billionaire who is unable to qualify for the contests because he is not accepting campaign donations. But even if he’s not on the podium, Bloomberg has been felt in the state: He’s running a deluge of TV advertising in California to introduce himself to voters who probably know little, if anything, about him. Bloomberg’s late entry into the contest last month highlighted the overriding issue in the contest, electability, a sign of the unease within the Democratic Party about its crop of candidates and whether any is strong enough to unseat an incumbent president. The eventual nominee will be tasked with splicing together the party’s disparate factions — a job Hillary Clinton struggled with after defeating Sanders in a long and bitter primary fight in 2016. Biden adviser Symone Sanders said to expect another robust exchange on health care. “This is an issue that is not going away and for good reason, because it is an issue that in 2018 Democrats ran on and won,” she said. Jess O’Connell with Buttigieg’s campaign said the candidate will “be fully prepared to have an open and honest conversation about where there are contrast between us and the other candidates. This is a really important time to start to do that. Voters need time to understand the distinctions between these candidates.” The key issues: health care and higher education. The unsettled race has seen surges at various points by Biden, Warren, Sanders and Buttigieg, though it’s become defined by that cluster of shifting leaders, with others struggling for momentum. California Sen. Kamala Harris, once seen as among the top tier of candidates, shelved her campaign this month, citing a lack of money. And Warren has become more aggressive, especially toward Buttigieg, as she tries to recover from shifting explanations of how she’d pay for “Medicare for All” without raising taxes. In a replay of 2016, the shifting race for the Democratic nomination has showcased the rift between the party’s liberal wing, represented in Sanders and Warren, and candidates parked in or near the political center, including Biden, Buttigieg and Bloomberg. Two candidates who didn’t make the stage will still make their presence felt for debate watchers with ads reminding viewers they’re still in the race. New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker and former Housing Secretary Julián Castro are airing television ads targeted to primary voters during the debate. Booker’s is his first television ad, and in it he says even though he’s not on the debate stage, “I’m going to win this election anyway.” It’s airing as part of a $500,000 campaign, running in Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada and South Carolina, as well as New York, Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles. A pro-Booker super PAC is also going up with an ad in Iowa highlighting positive reviews of Booker’s past debate performances. Meanwhile, Castro is running an ad, in Iowa, in which he argues the state should no longer go first in Democrats’ nominating process because it doesn’t reflect the diversity of the Democratic Party. Both candidates failed to hit the polling threshold to qualify for the debates and have in recent weeks become outspoken critics of what they say is a debate qualification process that favors white candidates over minorities. By Kathleen Ronayne and Michael R. Blood Associated Press Associated Press writer Michelle L. Price in Las Vegas contributed to this report. Catch up on the 2020 election campaign with AP experts on our weekly politics podcast, “Ground Game.” Republished with the Permission of the Associated Press.

A lot of holes in GOP presidential ground game in key states

Presidential battleground states were supposed to be swarming with Republican Party workers by now. “We’ve moved on to thousands and thousands of employees,” party chairman Reince Priebus declared in March, contrasting that with the GOP’s late-blooming staffing four years earlier. “We are covering districts across this country in ways that we’ve never had before.” That hasn’t exactly happened, a state-by-state review conducted by The Associated Press has found. With early voting beginning in less than three months in some states, the review reveals that the national GOP has delivered only a fraction of the ground forces detailed in discussions with state leaders earlier in the year. And that is leaving anxious local officials waiting for reinforcements to keep pace with Democrat Hillary Clinton in the states that matter most in 2016. To be sure, the national party actually has notched record levels of fundraising over the past few years and put together a much more robust ground game than it had in 2012. But officials acknowledge the real competition isn’t their past results or the chronically cash-strapped Democratic Party. It’s Clinton and what GOP party chairman Reince Priebus calls “that machine” of Clinton fundraising. Some examples of Republican shortfalls: Ohio Republicans thought they were going to see 220 paid staffers by May; in reality, there are about 50. Plans for Pennsylvania called for 190 paid staffers; there are about 60. Iowa’s planned ground force of 66 by May actually numbers between 25 and 30. In Colorado, recent staff departures have left about two dozen employees, far short of the 80 that were to have been in place. AP learned of the specific May staffing aims from Republicans who were briefed earlier this year; the RNC did not dispute them. Current totals came from interviews with local GOP leaders over the past two weeks. The gulf between what state leaders thought they could count on and what they’ve actually got comes as RNC’s ground game is asked to do more than ever before. Presumptive nominee Donald Trump is relying on the party to do most of the nuts-and-bolts work of finding and persuading voters in the nation’s most competitive battlegrounds. “This is a race we should win,” Ohio GOP chairman Matt Borges said, citing a voter registration boom. “Now, we have to put the people in the field.” In New Hampshire, a swing state that also features one of the nation’s most competitive Senate contests, the Republican National Committee’s original plan called for more than 30 paid staff on the ground by May. Yet what’s happening there highlights that even when the RNC is close to meeting its staffing goals, there can be problems. In this case, 20 positions have been converted to part-time, and local officials have been struggling to fill them. “It’s a tall order to ask the RNC to be the complete field operation for the presidential nominee,” said Steve Duprey, a national party committeeman from New Hampshire. “We’re following through on the plan, but it was slower being implemented than we first would have hoped.” Borges and Duprey, like Republican leaders across the nation, acknowledged that the national party has dramatically reduced its staffing plans in recent months. “You discuss idealistic, you discuss realistic,” said the RNC’s political director Chris Carr. “Some people hear what they want to hear.” The Democrats have been more focused. The GOP’s foes, says party chairman Priebus, “have built their program around a candidate.” By that measure, Clinton and her Democratic allies appear to be quite far ahead, with roughly double the staff of the Republicans in Ohio, for example. For anyone – party or candidate – ground operations are expensive. The RNC’s 242-person payroll cost $1.1 million in May, federally-filed financial documents show. Additionally, the party transfers hundreds of thousands of dollars each month to state parties, which in turn hire more people. Between direct RNC employees and state employees hired with the help of transfers, the party counts more than 750 staff members, including 487 spread across the country and concentrated in battleground states. By contrast, at this point in 2012, there were just 170 paid Republican operatives across the country. Party officials say they are confident they will raise enough money to maintain – and very likely boost – the current level of employees until Election Day. Trump, who did not actively raise money during the primary season, touted surprisingly strong fundraising numbers in late May and June, including $25 million that will be shared with the party. But it was the primary triumph of Trump in May – and the fact that he did not bring with him a hefty portfolio of donors – that derailed the party’s fundraising and hiring goals, party officials said. The timing was important because a nominee typically serves as a major fundraiser for the national party, and having one in March or April would have given the Republicans a boost. A sign on an office door in Sarasota, Florida, illustrates how critical the RNC will be to Trump’s bid for the White House. It’s Trump’s state headquarters. “THANKS FOR STOPPING BY OUR OFFICE!” the blue paper reads. “Our office is TEMPORARILY CLOSED to the public, while our office works to prep for the National Convention in Cleveland.” A phone call to the number on the sign ended with an automated message stating, “Memory is full.” The Republican Party has 75 employees on the ground in Florida – a few dozen shy of Clinton – but they aren’t seamlessly integrated with the Trump campaign. “I do see cooperation between the national party and the Trump campaign,” said Michael Barnett, chairman of the Palm Beach County GOP. “But that hasn’t materialized at the local level yet. That doesn’t mean it won’t happen. It’s a little bit of a late start, but I’m not nervous. Not yet.” Like Florida, Ohio and New Hampshire, Wisconsin is a presidential battleground that features a highly competitive Senate race. That means national party staffers have the dual task

Kevin Sweeny: Ground game — do or die

In the election of 1840, Abraham Lincoln served as a Whig presidential elector in Illinois. In his push to elect the “Tippecanoe and Tyler, too” ticket, he sent a ten-point edict to all committee members containing a field plan of operations. Much has changed in the landscape of political campaigns since 1840, but the importance of a well-organized, strong field operation has never waned. It is a mainstay in the campaigning ecosystem and part of a successful formula to forge a path to victory and campaigns which ignore its impact, do so at their own candidate’s peril. A generation ago, many political scientists were signaling the death of the ground game. TV, mail and even the Internet would render such campaign expenditures obsolete. However, over the last few election cycles, the opposite has proved true. Moreover, deeply established ground games have had a tremendous impact in municipal and state elections, local referendums and state ballot initiatives, to federal elections. Recent cycles have confirmed staffing a field operations campaign with a well-trained and competent workforce to help a candidate interact voters still matters. From getting petitions signed, voters registered, identifying early voters, canvassing door to door, and staffing the polls on Election Day, field campaigns still matter. Their greatest impact is at the local and state levels. Despite this, field operation’s budgets pale in comparison to advertisements. However, in-person mobilization appears to be one of the more effective expenditures a campaign can make with limited resources, increasing voter turnout by as much as 10 percent according to a recent study. Contemporary political campaigns utilize a broad set of tools and methods for finding and contacting voters, more than at any point in electoral history. Much has been written about the roles of technology, big data and social media in recent campaigns. However, at the same time, there has been a corresponding rise in old-fashioned campaign techniques, particularly establishing a competent ground game. Field offices, typically but not always placed in strategic locations around a district or state help to transform basic campaign information into real voter contacts. Field offices often serve as the first and last point of contact between a political campaign and the electorate. A campaign’s headquarters gathers important and timely information on voters and in turn relays such information to the field manager. They, in turn, instruct their field workers to pinpoint a calculated message to a structured group of voters. Typically, the most effective of these field workers are well-trained volunteers who live locally. While campaigns rely on a certain percentage of outside paid field workers, by far these local volunteers are most successful in distributing campaign information. Campaign volunteers are typically true believers in a cause, person or organization. They usually act purely on the belief they are making their community a better place. While obviously paid workers are vital to a campaign, no one was ever paid to start a real revolution. A first-rate example of the impact of a competent ground game is best illustrated by recent presidential elections and field work impact. Because the Democratic Party keeps better field data than the Republican Party, I will use them as an example. In a recent experiment, the 2012 presidential election was replicated with all things being equal. However, in this replication, Obama had no real field offices for volunteers. The results showed Obama would have lost 248,000 votes nationwide. A further dive into these numbers points to Obama losing Florida and therefore the presidency. Continued runs by political scientists Seth Masket, Josh Darr and Matthew Levendusky show running the same field simulations in the 2008 election gave Obama his victory in North Carolina, Florida and Indiana. Recent claims of Obama being able to win the presidency without a ground game simply do not hold water. After a recent election, a British Election Study showed one-on-one field contact made all the difference in local campaigns, by as much as 14 percent. Furthermore, a simple face-to-face meeting at the door by a campaign or candidate yielded a 97 percent likelihood of the voter casting their ballot for those who made contact with them. Moreover, the study showed it is not just a one-time face-to-face contact which matters, the contact must be constant. Parties lost upward of 16 percent of those who were only approached at the door once and never followed up on. Suffice to say, field offices increase turnout and vote share for the candidates and organizations who take the time to adequately fund and staff them. Lastly, and one of my personal favorite incentives of producing a solid ground game on top of being able to ascertain if your campaign’s message is resonating among the electorate is it creates a legion of loyal volunteers who are prepared to carry on the legacy of the candidate or party. This legacy of political skill can prove to be invaluable not only to the volunteer but to the organization and the electorate as a whole. Well trained and passionate volunteers evolve into the next generation of campaign managers, consultants and operatives. They understand not only the complexities associated with running a political campaign, but they also make meaningful connections with the governing, consultant and economic classes. Moreover, they gain a broader understanding of the issues faced by the electorate and the campaign they represent. Some will even eventually step into the fray and become candidates themselves. Two examples of this evolving legacy quickly come to mind. The first is the losing “YES!” campaign for Scottish independence which morphed its field operation into a supportive role for the SNP (Scottish National Party). In return, the field campaigns for “YES!” handed the SNP the most seats in their party’s history and now the SNP is the outright ruling party in Holyrood. Another example much closer to home is Jeb Bush’s grassroots push on education issues dating as far back as his first unsuccessful run for Governor in 1994. The political initiatives are still pushed by a network of