Alabama’s higher ed funding cuts since 2008 are country’s third deepest

Alabama’s cuts to state higher education funding over the last decade are among the deepest in the country, according to a new report from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), a nonpartisan research organization based in Washington, D.C. The funding decline persisted even as the state’s economy began to rebound from the Great Recession. Since 2008, Alabama has slashed state higher education funding by 34.6 percent or $4,290 per student, CBPP found. The state’s cuts are the nation’s third worst by dollar amount and fifth worst by percentage. Nationally, the average cuts since 2008 are 16 percent or $1,502 per student. Alabama’s inadequate public investment in higher education over the last decade has contributed to rising tuition prices, often leaving students with little choice but to take on more debt or give up on their dreams of going to college. Between 2008 and 2018, the average tuition at public four-year institutions in Alabama jumped by $4,329, or 69.8 percent – far outpacing the national average growth of 36 percent. These soaring costs have seemingly erected barriers to opportunity for young people across Alabama, particularly for black, Hispanic and low-income students. “Pushing the cost of college onto students and their families will not make our state stronger,” said Carol Gundlach, policy analyst for Alabama Arise, a nonprofit, nonpartisan coalition of congregations, organizations and individuals promoting public policies to improve the lives of low-income Alabamians. “We must invest adequately in higher education to be able to build an Alabama where everyone has the opportunity to succeed.” In Alabama, a college education is even less affordable than many other states across the country , especially for black and Hispanic families. In 2017, the average tuition and fees at a public four-year university accounted for: 21 percent of median household income for all Alabama families. 32.2 percent of median household income for black families in Alabama. 26.8 percent of median household income for Hispanic families in Alabama. “The rising cost of college risks blocking one of America’s most important paths to economic mobility,” explained CBPP senior policy analyst Michael Mitchell, the report’s lead author. “And while these costs hinder progress for everyone, black, Hispanic and low-income students continue to face the most significant barriers to opportunity.” Student debt Financial aid has failed to bridge the gap created by rising tuition and relatively stagnant incomes. As a result, the share of students graduating with debt has increased. Between 2008 and 2015, the share of students graduating with debt from a public four-year institution rose from 55 percent to 59 percent nationally. The average amount of debt also increased during this period. On average, bachelor’s degree recipients at four-year public schools saw their debt grow by 26 percent (from $21,226 to $27,000). By contrast, the average amount of debt rose by only about 1 percent in the six years prior to the recession. A large and growing share of future jobs will require college-educated workers. Alabama Arise believes greater public investment in higher education, particularly in need-based aid, would help Alabama develop the skilled and diverse workforce it needs to match the jobs of the future. “All Alabamians, regardless of their income or where they grow up, deserve an opportunity to reach their full potential,” Gundlach added. “Our state should end tax breaks for large corporations and invest in making college more affordable for the students who need assistance the most.”

Del Marsh, Arthur Orr seek accountability for higher education spending

Facing a perennial budget shortfall, the Alabama Legislature is forced to consider how to best spend each and every hard-earned taxpayer-dollar each year. Which is exactly why Anniston-Republican Sen. Del Marsh and Decatur-Republican Sen. Arthur Orr submitted a plan in the Alabama Legislature that seeks to establish greater accountability for the state’s higher education spending by creating the Alabama Community College Council on Outcome-Based Funding. The council would be tasked with rethinking the current postsecondary funding model and create a plan to shift to outcome-based funding for Alabama’s community colleges. Like many state across the country, Alabama currently allocates funds on the basis of enrollment, which by-and-large ensures equitable distribution of per-student spending across institutions. Essentially, dollars follow students high school to higher education. But the current system doesn’t always take in account whether or not students complete their college courses, transfer to other institutions, or even graduate. Which is why Marsh and Orr are hoping to change the system to one where dollars don’t simply follow students, but rather they follow successful students, by shifting the funding to what educators call an outcome-based or performance-based system. Switching to an outcome-based system, endeavors to ensure taxpayer investments yield the best possible returns as they incentivize not only college access, but also college completion “The goal here is to bring more accountability to taxpayer dollars that are spent by higher education institutions,” Orr remarked. “The Legislature appropriates over $1.5 billion annually to Alabama’s colleges and universities, and we need a mechanism for rewarding those institutions that are providing great value to Alabama’s students.” According to the plan set forth — Senate Joint Resolution 85 — an advisory council will develop a specific outcome-based funding model for the allocation of Education Trust Fund appropriations to publicly-supported community and technical colleges in Alabama. “Making government more accountable to the taxpayers is a top priority of the Alabama Legislature,” Marsh said. “We are committed to making any changes necessary in order to achieve that goal.” Alabama isn’t the only state looking to make a change. Across the country, other budget-strapped states have been forced to carefully consider how their limited dollars are spent on higher education. Currently, thirty-two states — including neighbor-states Florida, Georgia, and Tennessee — now use, or are in the process of transitioning to performance-based formulas to determine higher education spending. “Historically, many colleges have received state funding based on how many full-time equivalent students are enrolled at the beginning of the semester,” said the National Conference of State Legislatures. This model provides incentives for colleges to enroll students and thus provide access to postsecondary education, but this model does not necessarily provide incentives for institutions to help students successfully complete degree programs. Many states are reconsidering the enrollment-based funding model and instead are aligning funding models with state goals and priorities.” Pending what the advisory council puts together, Alabama could be poised to join them soon. A shift in process could not only help the state’s ongoing budget crisis, but also bolster state’s higher education graduation rate. Only 23.5 percent of Alabamians between the ages of 25 and 64 have an associate’s degree or better. In comparison, 40.4 percent of Americans in the same demographic do, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2011-2015 data. “This process is in line with our vision of providing all Alabamians with an affordable pathway to succeed through quality education and training,” said Jimmy Baker, Chancellor of the Alabama Community College System. “We look forward to working with the Legislature to create a funding model that ensures we are accountable with every dollar provided to us and shows the successes of our students.” According to SJR85, “the advisory council shall report its findings, conclusions, and recommendations to the Governor, the Chair of the House Ways and Means Education Committee, and the Chair of the Senate Finance and Taxation Education Committee not later than January 1, 2018” to be considered during the 2018 Legislative Session.

The new civics course in schools: How to avoid fake news

Teachers from elementary school through college are telling students how to distinguish between factual and fictional news — and why they should care that there’s a difference. As Facebook works with The Associated Press, FactCheck.org and other organizations to curb the spread of fake and misleading news on its influential network, teachers say classroom instruction can play a role in deflating the kind of “Pope endorses Trump” headlines that muddied the waters during the 2016 presidential campaign. “I think only education can solve this problem,” said Pat Winters Lauro, a professor at Kean University in New Jersey who began teaching a course on news literacy this semester. Like others, Lauro has found discussions of fake news can lead to politically sensitive territory. Some critics believe fake stories targeting Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton helped Donald Trump overcome a large deficit in public opinion polls, and President Trump himself has attached the label to various media outlets and unfavorable reports and polls in the first weeks of his presidency. “It hasn’t been a difficult topic to teach in terms of material because there’s so much going on out there,” Lauro said, “but it’s difficult in terms of politics because we have such a divided country and the students are divided, too, on their beliefs. I’m afraid sometimes that they think I’m being political when really I’m just talking about journalistic standards for facts and verification, and they look at it like ‘Oh, you’re anti-this or -that.’” Judging what to trust was easier when the sources were clearer — magazines, newspapers or something else, said Kean senior Mike Roche, who is taking Lauro’s class. Now “it all comes through the same medium of your cellphone or your computer, so it’s very easy to blur the lines and not have a clear distinction of what’s real and what’s fake,” he said. A California lawmaker last month introduced a bill to require the state to add lessons on how to distinguish between real and fake news to the grade 7-12 curriculum. High school government and politics teacher Lesley Battaglia added fake news to the usual election-season lessons on primaries and presidential debates, discussing credible sites and sources and running stories through fact-checking sites like Snopes. There were also lessons about anonymous sources and satire. (They got a kick out of China’s dissemination of a 2012 satirical story from The Onion naming Kim Jong Un as the sexiest man alive.) “I’m making you guys do the hard stuff that not everybody always does. They see it in a tweet and that’s enough for them,” Battaglia told her students at Williamsville South High School in suburban Buffalo. “It’s kind of crazy,” 17-year-old student Hannah Mercer said, “to think about how much it’s affecting people and swaying their opinions.” Stony Brook University’s Center for News Literacy pioneered the idea of educating future news consumers, and not just journalists, a decade ago with the rise of online news. About four in 10 Americans often get news online, a 2016 Pew Research Center report found. Stony Brook last month partnered with the University of Hong Kong to launch a free online course. “To me, it’s the new civics course,” said Tom Boll, after wrapping up his own course on real and fake news at the Newhouse School at Syracuse University. With everyone now able to post and share, gone are the days of the network news and newspaper editors serving as the primary gatekeepers of information, Boll, an adjunct professor, said. “The gates are wide open,” he said, “and it’s up to us to figure out what to believe.” That’s not easy, said Raleigh, North Carolina-area teacher Bill Ferriter, who encourages students to first use common sense to question whether a story could be true, to look at web addresses and authors for hints, and to be skeptical of articles that seem aimed at riling them up. He pointed to an authentic-looking site reporting that President Barack Obama signed an order in December banning the Pledge of Allegiance in schools. A “.co” at the end of an impostor news site web address should have been a red flag, he said. “The biggest challenge that I have whenever I try to teach kids about questionable content on the web,” said Ferriter, who teaches sixth grade, “is convincing them that there is such a thing as questionable content on the web.” Some of Battaglia’s students fear fake news will chip away at the trust of even credible news sources and give public figures license to dismiss as fake news anything unfavorable. “When people start to distrust all news sources is when people in power are just allowed to do whatever they want, said Katie Peter, “and that’s very scary.” Republished with permission of The Associated Press.

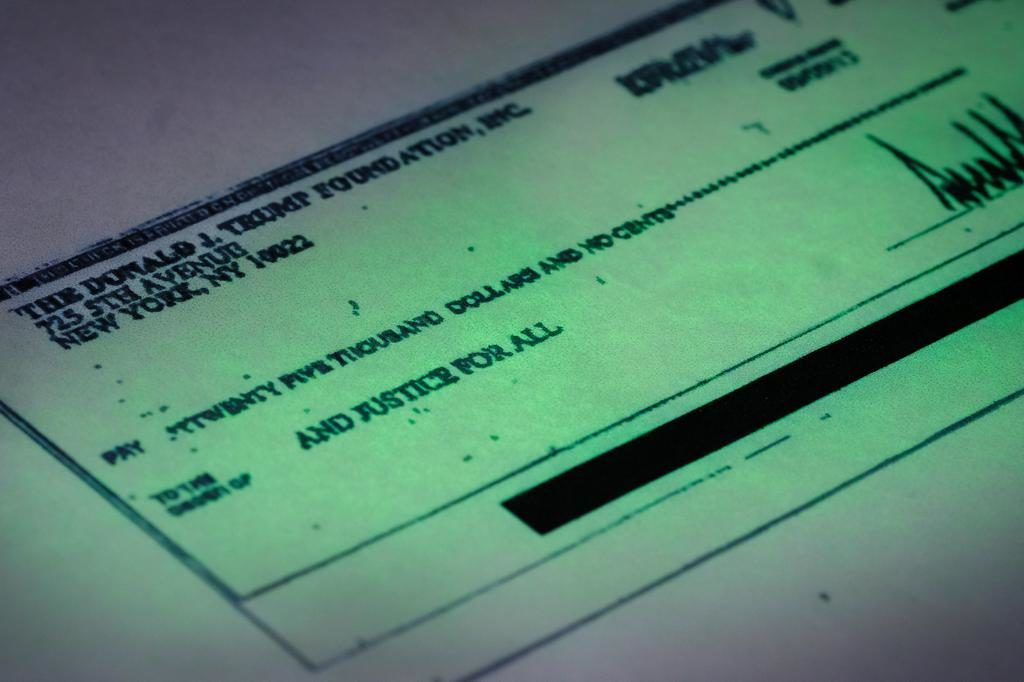

Donald Trump signed improper charity check supporting Florida AG Pam Bondi

Donald Trump‘s signature, an unmistakable if nearly illegible series of bold vertical flourishes, was scrawled on the improper $25,000 check sent from his personal foundation to a political committee supporting Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi. Charities are barred from engaging in political activities, and the Republican presidential nominee’s campaign has contended for weeks that the 2013 check from the Donald J. Trump Foundation was mistakenly issued following a series of clerical errors. Trump had intended to use personal funds to support Bondi’s re-election, his campaign said. So, why didn’t Trump catch the purported goof himself when he signed the foundation check? Trump lawyer Alan Garten offered new details about the transaction to The Associated Press on Thursday, after a copy of the Sept. 9, 2013, check was released by New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman. Garten said the billionaire businessman personally signs hundreds of checks a week, and that he simply didn’t catch the error. “He traditionally signs a lot of checks,” said Garten, who serves as in-house counsel for various business interests at Trump Tower in New York City. “It’s a way for him to monitor and keep control over what’s going on in the company. It’s just his way. … I’ve personally been in his office numerous times and seen a big stack of checks on his desk for him to sign.” The 2013 donation to Bondi’s political group has garnered intense scrutiny because her office was at the time fielding media questions about whether she would follow the lead of Schneiderman, who had then filed a lawsuit against Trump University and Trump Institute. Scores of former students say they were scammed by Trump’s namesake get-rich-quick seminars in real estate. Bondi, whom the AP reported in June personally solicited the $25,000 check from Trump, took no action. Both Bondi and Trump say their conversation had nothing to do with the Trump University litigation, though neither has answered questions about what they did discuss or provided the exact date the conversation occurred. House Democrats called earlier this week for a federal criminal investigation into the donation, suggesting Trump was trying to bribe Bondi with the charity check. Schneiderman, a Democrat, said he was already investigating to determine whether Trump’s charity broke state laws. Garten said the series of errors began after Trump instructed his staff to cut a $25,000 check to the political committee supporting Bondi, called And Justice for All. Someone in Trump’s accounting department then consulted a master list of charitable organizations maintained by the IRS and saw a Utah charity by the same name that provides legal aid to the poor. According to Garten, that person, whom he declined to identify by name, then independently decided that the check should come from the Trump Foundation account rather than Trump’s personal funds. The check was then printed and returned for Trump’s signature. After it was signed, Garten said, Trump’s office staff mailed the check to its intended recipient in Florida, rather than to the charity in Utah. Emails released by Bondi’s office show her staff was first contacted at the end of August by a reporter for The Orlando Sentinel asking about the Trump University lawsuit in New York. Trump’s Sept. 9 check is dated four days before the newspaper printed a story quoting Bondi’s spokeswoman saying her office was reviewing Schneiderman’s suit, but four days before the pro-Bondi political committee reports receiving the check in the mail. Compounding the confusion, the following year on its 2013 tax forms the Trump Foundation reported making a donation to a Kansas charity called Justice for All. Garten said that was another accounting error, rather than an attempt to obscure the improper donation to the political group. In March, The Washington Post first revealed that that the donation to the pro-Bondi group had been misreported on the Trump Foundation’s 2013 tax forms. The following day, records show Trump signed an IRS form disclosing the error and paying a $2,500 fine. Bondi has endorsed Trump’s presidential bid and has campaigned with him this year. She has said the timing of Trump’s donation was coincidental and that she wasn’t personally aware of the consumer complaints her office had received about Trump University and the Trump Institute, a separate Florida business that paid Trump a licensing fee and a cut of the profits to use his name and curriculum. Neither company was still offering seminars by the time Bondi took office in 2011, though dissatisfied former customers were still seeking promised refunds. Republished with permission of the Associated Press.

College-educated whites put hole in Donald Trump coalition

Wanda Melton has voted for every Republican presidential nominee since Ronald Reagan in 1980, but now the Georgia grandmother plans to cross over to support Democrat Hillary Clinton. “I’m not a real fan of Hillary,” Melton says from her office in Atlanta. “But I think it would just be awful to have Donald Trump.” She adds: “I cannot in good conscience let that happen.” Melton is among a particular group of voters, whites with college degrees, who are resistant to Trump. Their skepticism comes as an ominous warning as Trump struggles to rebuild even the losing coalition that Mitt Romney managed four years ago. College-educated whites made up more than one-third of the electorate in 2012. Polls suggest Trump trails Clinton with those voters, especially women. “Donald Trump simply cannot afford to lose ground in any segment of the electorate” that supported Romney, said Florida pollster Fernand Amandi. Romney’s strength with that group, for example, made for a close race in Florida, where President Barack Obama won by less than 75,000 votes out of more than 8.4 million cast. Some Republicans worry Trump’s approach — his unvarnished, sometimes uncouth demeanor and his nationalist and populist arguments — guarantees his defeat, because the same outsider appeal that attracts many working class and even college-educated white men alienates other voters with a college degree. Ann Robinson, 64, is a lifelong Republican in a Trump’s home state of New York, a Democratic stronghold that the real estate tycoon cites as an example of where he can “expand the map.” Robinson sneers at the proposition and says she’ll vote for Clinton. “It’s just not a reasonable movement,” she says of Trump’s populist pitch. “I’m not sure he can actually be their savior. She has so much more experience. Trump has nothing.” Mary Darling, 59, is an Illinois Republican who said she won’t vote for Trump or Clinton. “If they could just soften his edges, people would flock to him, but that’s just not going to happen,” she said. Lew Oliver, chairman of the Orange County Republican Party in Florida, says he’s prepared for an uphill fight in no small part because of Trump’s struggle among more educated voters. “The fundamentals aren’t in our favor, and some of his comments aren’t helping,” Oliver said. Romney drew support from 56 percent of white voters with college degrees, according to 2012 exit polls. Obama notched just 42 percent, but still cruised to a second term. A Washington Post-ABC News poll taken in June found Clinton leading Trump among college-educated whites 50 percent to 42 percent. Polling from the nonpartisan Pew Research Center pointed to particularly stark numbers among white women with at least a bachelor’s degree. At this point in 2008 and 2012, that group of voters was almost evenly divided between Obama and the Republican nominee. This June, Pew found Clinton with a 62-31 advantage. Conversely, Pew found Trump still leads, albeit by a slightly narrower margin than did Romney at this point, among white women with less than a bachelor’s degree. Should Trump fail to even replicate Romney’s coalition, he has little hope of flipping many of the most contested states that Obama won twice, particularly Florida, Colorado and Virginia. Trump’s struggles among college whites have Democrats eyeing North Carolina, which Obama won in 2008 before it reverted back to Republicans, and even GOP-leaning Arizona and Georgia. The education gap for Trump isn’t new. Exit polls in the Republican primaries found him faring better among less educated groups. Trump particularly struggled with better-educated Republicans when Florida Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., was in the presidential race. Republican pollster Greg Strimple of Idaho says the gap is understandable. Voters without a college education, he said, are more likely to be struggling financially, to feel alienated from the political class Trump rails against and to find solace in his promise to stop illegal immigration. College educated voters “may have had relatively stagnant incomes, but they can still look at their 401(k)s and think about the future,” Strimple said. “They’re free to care more about things like tone.” Clinton’s campaign sees the persuadable portion of the electorate as being made up largely of women, many with college degrees. It has tried to reach them by hammering Trump as “dangerous” and “temperamentally unfit” for the job, while her initial general election advertising blitz focuses on her achievements in public life. Strimple said Trump must counter that with a constant “indictment of the last eight years, an indictment of Hillary Clinton. That can get some of those voters back.” The question for Trump, though, is how many Wanda Meltons are already lost. “He’s just not in control of himself,” she says. “That personality type is not suited either to leadership or protecting the country.” Republished with permission of the Associated Press.