Curfews, pandemic test voters in primaries held amid unrest

In all, nine states and the District of Columbia held elections, including four that delayed their April contests.

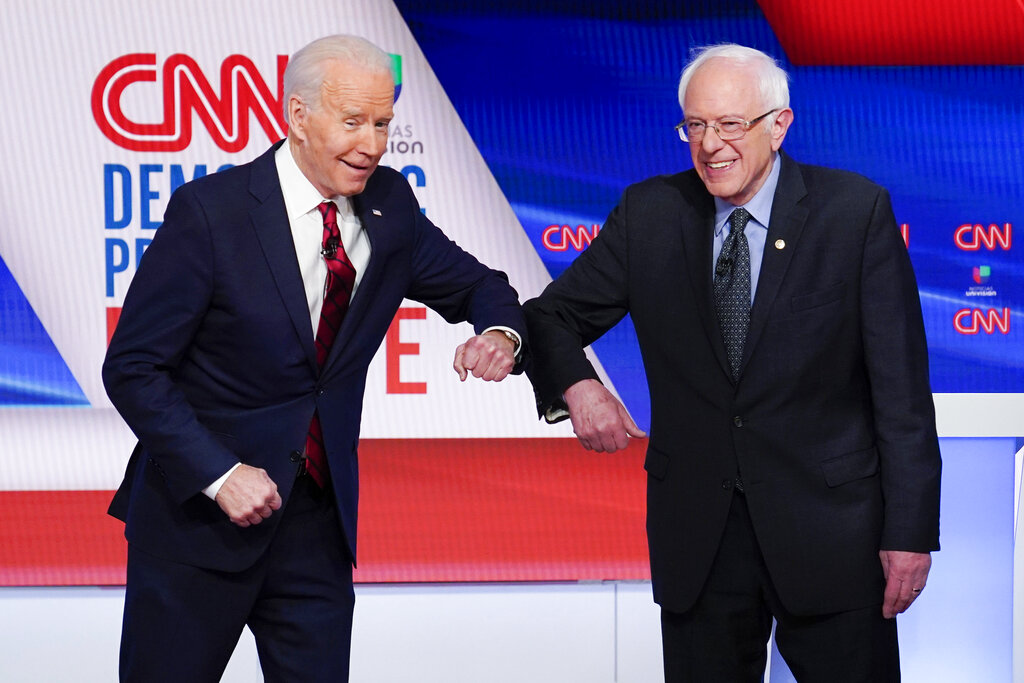

Joe Biden reaches deal to let Bernie Sanders keep hundreds of delegates

Under party rules, Sanders should lose about one-third of the delegates he’s won.

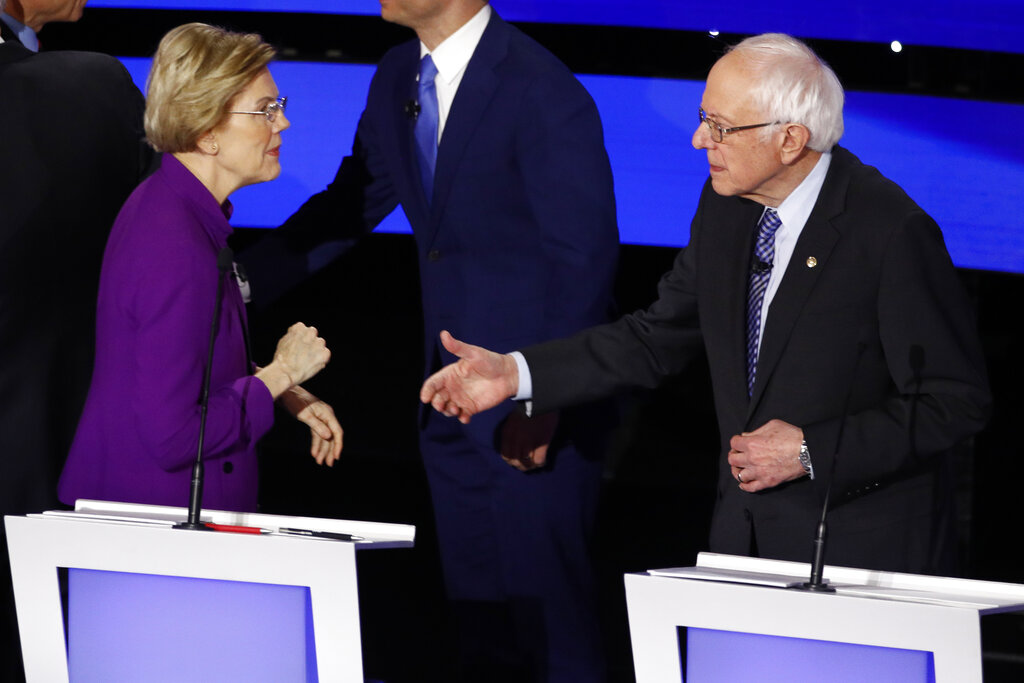

Bernie Sanders struggles to expand supporter base after Elizabeth Warren exit

Elizabeth Warren declined to endorse anyone when she suspended her campaign for President.

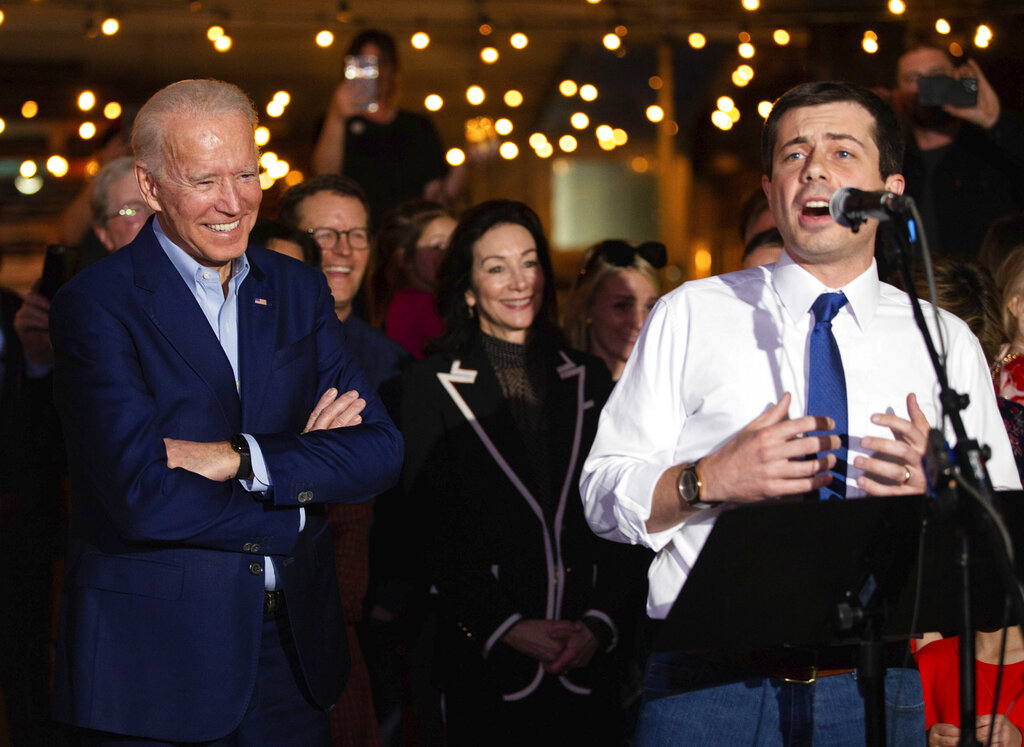

On Super Tuesday eve, Joe Biden gets boost from former rivals

Biden received the support of former rivals, Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar.

Worried Democrats rush to slow front-runner Bernie Sanders

A new political group was spending big to undermine Sanders’ standing with African American voters.

Democrats won’t commit to same-day release of Nevada results

Nevada Democrats are hoping to avoid a repeat of the chaos that ensnared the Iowa caucuses this month.

Democrats struggle to build broad support on eve of voting

Polling suggests each of the leading candidates has glaring holes in his or her political bases.

Elizabeth Warren-Bernie Sanders rift has progressives nervous about fallout

The rift stems from a private conversation in 2018.

Bernie Sanders didn’t think woman could win Presidency, Elizabeth Warren says

The statement drew a swift and strong denial from Bernie Sanders.

Primary odd couple pushes to unite Democratic party

It seemed like a surprising party of two. There was Robby Mook, Hillary Clinton‘s top campaign aide, known for his calm temperament and fiercely disciplined ways, and Jeff Weaver, a combative political fighter often called Bernie Sanders‘ alter ego, sharing a Friday night dinner at The Farmhouse Tap & Grill in Burlington, Vermont. But over the long months of a frequently contentious primary, the two rival Democratic campaign managers struck up an unusually friendly relationship, founded on exhaustion, goofy jokes and a shared affection for their home state of Vermont. They talk almost daily, text frequently and email often. Now, as Sanders lingers in the presidential race, refusing to concede the nomination to Clinton even as he says he’ll vote for her on Election Day, the competing campaign managers have become a powerful political odd couple, responsible for engineering a graceful conclusion to a hard-fought Democratic contest. “I’ve really come to respect him,” Mook said. “There were some tense moments, but he was always honest, straightforward and very easy to work with.” Weaver is equally effusive in his praise. “I think he’s the kind of guy who is doing what he does for the right reasons,” Weaver said about Mook. “He believes in the cause and he believes in making the world a better place.” After Clinton and Sanders met at Washington hotel this month, their managers stayed until almost midnight, attempting to hammer out an agreement that would give Sanders some of the changes he wants to make to the party’s platform. During his Friday trip to Vermont, Mook made sure to meet with Sanders supporters. Some of the communication hints at far closer cooperation to come. The two camps are increasingly comparing notes on how best to attack presumptive GOP nominee Donald Trump. Clinton’s campaign and state Democratic parties have hired some Sanders staffers, and there is chatter about joint events to come. Both Mook and Weaver share a slightly silly sense of humor. Mook, 35, regales his fiercely loyal band of young operatives, known as the Mook Mafia, with impressions, including spot-on impersonations of Bill Clinton and Sanders. Weaver, 50, who owns and operated a Falls Church, Virginia, comic book and gaming store before taking the helm of Sanders’ campaign, made up gag business cards at the start of the campaign describing himself as the “comic book king.” “His Bill Clinton is pretty good,” Weaver said of Mook. “It’s not only the voice, but it’s the subject matter.” But their back-channel negotiations are nothing but serious. While Clinton has largely unified Democratic leadership around her bid, she’s struggling to win over the young and liberal voters who supported Sanders, a Vermont senator. Sanders is pushing for ways of addressing key economic issues in the Democratic platform, including trade, providing free college tuition and expanding Medicare and Social Security. “Right now, what we are doing is trying to say to the Clinton campaign, stand up, be bolder than you have been. And then many of those voters, in fact, may come on board,” Sanders told CNN’s “State of the Union” on Sunday. He also wants procedural changes, such as allowing independents to participate in primaries and curtailing the role of superdelegates — the party leaders who help determine the party’s nominee. On Friday, Sanders told MSNBC that he would vote for the former secretary of state. But he shied away from offering a formal endorsement or urging his supporters to back her. Instead, he’s kicked off a new phase of his “political revolution,” campaigning on behalf of like-minded Democrats who are running for Congress or local office. To close that gap, the candidates may rely on the personal rapport between their two top aides, a relationship helped along by formative years in Vermont politics. Weaver was raised in a rural, northern Vermont town. Mook, the son of a Dartmouth professor, grew up in Norwich, near the New Hampshire border. As a 20-year-old Boston University student, Weaver drove Sanders around the small state during Sanders’ unsuccessful campaign for governor. Mook’s first campaign memory: going to the dump to get petition signatures and distribute literature. While they knew of each other, the first time they met in person was in October, at the Iowa Democratic Party’s Jefferson-Jackson Dinner, a key stop for presidential candidates. Wearing matching outfits of khakis, blue blazers and Johnston & Murphy brown shoes, they posed for photos with their legs propped up on a security barrier. “His shoes were in better condition,” joked Mook. In New Hampshire, they were subjected to a series of interviews about each other’s campaigns — while sitting kitty-corner. The experience was remarkably friendly, Weaver recalled, allowing them to commiserate over the lack of sleep and endless travel that is part of a presidential campaign. After that, the conversation slowly expanded. Today, their relationship has grown far closer than that of their bosses. Though Clinton and Sanders have known each other since she came to Washington as first lady in 1993, they rarely communicate, say aides. Former President Bill Clinton, according to aides, was particularly frustrated by Sanders’ ability to cast himself as above politics-as-usual while firing off what he considered to be misleading attacks on Clinton’s White House legacy. For Weaver, his focus remains on ensuring that Sanders and his supporters are represented in the party and the platform that will be voted on at the Philadelphia convention. “It obviously is important that the secretary during the general election speaks to the aspirations of that 13 million people who voted for Bernie Sanders,” Weaver said. “It’s important those people be heard — not just feel like they’ve been heard — but be heard.” Republished with permission of The Associated Press.

Darryl Paulson: The trials and tribulations of Reince Priebus and Debbie Wasserman Schultz

When the 2016 presidential campaign began, everyone believed that Hillary Clinton would quickly wrap up the Democratic nomination since she faced what many saw as token opposition. It was the Republicans, who had enough candidates to field a football team, who were expected to have a bitter, protracted primary. As so often has been the case in 2016, conventional wisdom was dead wrong. Donald Trump, who most thought would never enter the primary process, who not only entered the primaries but tore his opponents to shreds. Trump did what Julius Caesar wrote about 2,000 years ago: He came. He saw and he conquered. Clinton, who was supposed to dominate the small and weak Democratic field, is still engaged in a long and increasingly bitter campaign with Bernie Sanders. It may well be the Democrats, not the Republicans, who find themselves in the midst of a contested national convention. Both parties are headed by individuals who have chaired the party for many years. Reince Priebus was perceived to have the most difficult job in expanding the party’s appeal to minorities and women while at the same time having a candidate who spat at vitriol at those groups as fast as he could Twitter. On the Democratic side, Debbie Wasserman Schultz has chaired the party since 2011. Managing the 2016 Democratic presidential campaign has been far more confrontational than she and fellow Democrats anticipated. Both Priebus and Schultz have faced a common problem: dealing with a candidate who believes the system is rigged, and the party establishment is doing whatever it can to defeat their campaign. Trump was considered such a loose cannon and political liability to the party that Priebus developed a loyalty oath procedure to prevent Trump from fleeing the party and mounting an independent or third-party campaign. Splitting the party would guarantee a Democratic victory in the fall. As difficult as it has been for Priebus to manage the Republicans, it has been even worse for Wasserman Schultz. From the very beginning, Sanders and his supporters have argued that Schultz has done everything possible to undermine his campaign. Sanders and his campaign manager Jeff Weaver have contended that Wasserman Schultz had “rigged the election” for Clinton. Few debates were scheduled, and when they were held, they were scheduled on weekends when viewership would be minimal. The Sanders campaign also alleged that the party chair denied them access to their own election data, and they had to sue to retrieve their own data. Finally, they argue that Wasserman Schultz appointed “hostile Hillary partisans” to key committees at the national convention. It is not just the Sanders campaign that is complaining about the biased conduct of the party chair. Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard, a DNC member, was critical of the number and scheduling of the debates. As a result, the chair revoked her invitation to the first Democratic presidential debate. Gabbard resigned from the DNC in protest. Van Jones, a CNN contributor and active Democrat, has complained that Wasserman Schultz, instead of being neutral, is “coming in harder for Hillary than she is for herself.” “I wish Reince Priebus was my party chair,” notes Jones. “He did a better job of handling the Trump situation than I’ve seen my party chair handle the situation.” MSNBC News host Chris Hayes summarized a common view of the bias of Wasserman Schultz for Clinton. “It is clearly the case when given truth serum, Debbie Wasserman Schultz vastly prefers Hillary Clinton to be the party’s nominee. . .” Mika Brzezinski, co-host of “Morning Joe” on MSNBC, has called on Wasserman Schultz to resign, and Joe Scarborough said that “If the party I was a member of treated me like this … I’d say, ‘Go straight to hell, I’m running as an independent.” Donald Trump has jumped in to support Sanders by saying that “Bernie Sanders is being treated very badly by the Democrats and the system is rigged against him.” Trump clearly benefits from a divided Democratic Party and has urged Sanders voters to support Trump in the fall. Wasserman Schultz’s management of the Democratic presidential race has created problems in her own re-election campaign. She is now facing a serious challenge from Tim Canova, a law professor at Nova Southeastern Law School. Canova has raised more than a million dollars to challenge Wasserman Schultz, an impressive amount for someone running against the chair of the Democratic Party. Wasserman Schultz has raised $1.8 million and has the support of both President Obama and Vice President Biden. But, for those who think Wasserman Schultz will easily win re-election, they might want to talk to former Republican Majority Leader Eric Cantor, who ended up losing to little-known professor Dave Brat. On the primary election night, Wasserman Schultz might recall the words of songwriter Leslie Gore: “It’s my party, and I’ll cry if I want to.” ••• Darryl Paulson is professor emeritus of government at USF St. Petersburg.