Voter turnout sagging in troubled voting rights hub of Selma

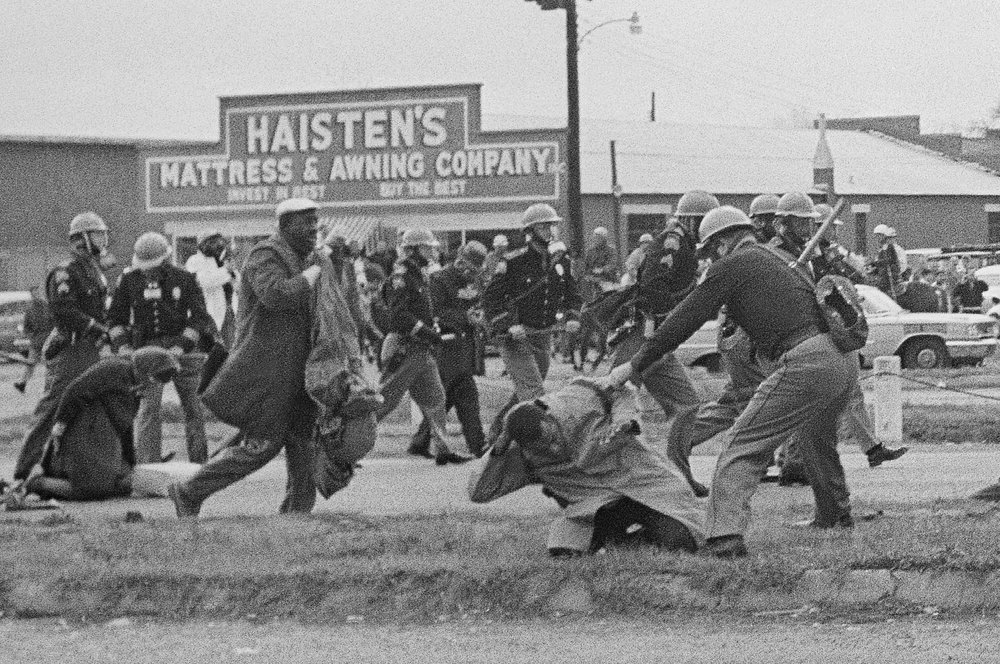

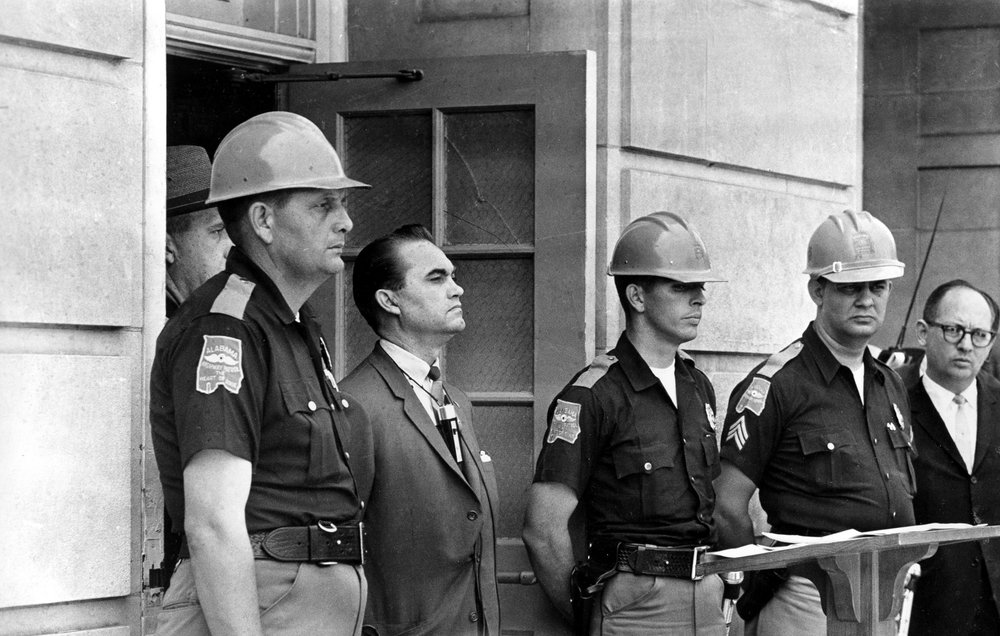

Fewer and fewer people are voting in Selma, Alabama. And to many, that is particularly heartbreaking. They lament that almost six decades after Black demonstrators on the city’s Edmond Pettus Bridge risked their lives for the right to cast ballots, voting in predominantly Black Selma and surrounding Dallas County has steadily declined. Turnout in 2020 was under 57%, among the worst in the state. “It should not be that way. We should have a large voter turnout in all elections,” said Michael Jackson, a Black district attorney elected with support from voters of all races. Thousands will gather on March 6 for this year’s re-enactment of the bridge crossing to honor the foot soldiers of that “Bloody Sunday” in 1965. Downtown will resemble a huge street festival during the event, known as the Selma Bridge Crossing Jubilee, with thousands of visitors, blaring music, and vendors selling food and T-shirts. Another Selma event, less celebratory and more activist, was held last year by Black Voters Matter. The aim was to boost Black power at the ballot box. But the issues in Selma — a onetime Confederate arsenal, located about 50 miles (80 kilometers) west of Montgomery in Alabama’s old plantation region — defy simple solutions. Some cite a hangover from decades of white supremacist voter suppression, others a 2013 Supreme Court ruling that gutted key provisions of federal voting law to allow current GOP efforts to tighten voting rules. Some Black voters, who tend to vote Democratic, simply don’t see the point in voting in a state where every statewide office is held by white Republicans who also control the Legislature. Then there is what some describe as infighting between local leaders, and low morale in a crime-ridden town with too many pothole-covered streets, too many abandoned homes, and too many vacant businesses. All are considered factors that helped lead to a 13% decline in population over the last decade in a town where more than one-third live in poverty. Despite visits from presidents, congressional leaders, and celebrity luminaries like Oprah Winfrey — and even the success of the 2014 historical film drama “Selma” by Ava DuVernay — Selma never seems to get any better. Resident Tyrone Clarke said he votes when work and travel allow, but not always. Many others don’t because of disqualifying felony convictions or disillusionment with the shrinking town of roughly 18,000 people, he said.ADVERTISEMENT “You have a whole lot of people who look at the conditions and don’t see what good it’s going to do for them,” Clarke said. “You know, ‘How is this guy or that guy being in office going to affect me in this little, rotten town here?’” But something else seems to be going on in Selma and Dallas County. Other poor, mostly Black areas have not seen the same drastic decline in turnout. Only one of Alabama’s majority Black counties, Macon, the home of historically Black Tuskegee University, had a lower voter turnout than Dallas in 2020. Selma is hardly the only place where big Black majorities don’t always translate to big voter turnout. The U.S. Census Bureau found that a racial gap persisted nationwide in voting in 2020, with about 71% of white voters casting ballots compared to 63% of eligible Black people. A majority of Dallas County’s voters are Black, and Black people made up the largest share of the county’s vote in 2020, about 68%, state statistics show. But white voters had a disproportionally larger share of the county electorate compared to Black voters, records showed. Jimmy L. Nunn, a former Selma city attorney who became Dallas County’s first Black probate judge in 2019, said the community is weighed down by its own history. “We have been programmed that our votes do not count, that we have no vote,” said Nunn, who works in the same county courthouse where white, Jim Crow officeholders refused to register Black voters, helping inspire the protests of 1965. “It is that mindset we have to change.” Selma entered voting rights legend because of what happened at the foot of the Edmond Pettus Bridge, which is named for a onetime Confederate general and reputed Ku Klux Klan leader, on March 7, 1965. After months of demonstrations and failed attempts to register Black people to vote in the white-controlled city, a long line of marchers led by John Lewis, then a young activist, crossed the span over the Alabama River headed toward the state capital of Montgomery to present demands to Gov. George C. Wallace, a segregationist. State troopers and sheriff’s posse members on horseback stopped them. A trooper bashed Lewis’ head during the ensuing melee and dozens more were hurt. Images of the violence reinforced the evil and depth of Southern white supremacy, helping build support for the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In the following decades, Selma became a worldwide touchstone for voting rights, with then-President Barack Obama speaking at the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday in 2015. “If Selma taught us anything, it’s that our work is never done,” he said. “The American experiment in self-government gives work and purpose to each generation.” But in Selma, voting already was on the decline. After more than 66% of Dallas County’s voters went to the polls in 2008, when Obama become the nation’s first Black president, turnout fell in each presidential election afterward. Shamika Mendenhall, a mother of two young children with a third on the way, was among registered voters who did not cast a ballot in 2020. She often goes to the annual jubilee that marks the anniversary of Bloody Sunday and has relatives who participated in voting rights protests of the 1960s, and she’s still a little sheepish about missing the election. “To choose our president we ought to vote,” said Mendenhall, 25. A Black member of the county’s Democratic Party executive committee, Collins Pettaway III spends a lot of time pondering how to get young voters like Mendenhall more engaged. Older residents who remember Bloody Sunday and the subsequent Selma-to-Montgomery voting rights march vote, he said,

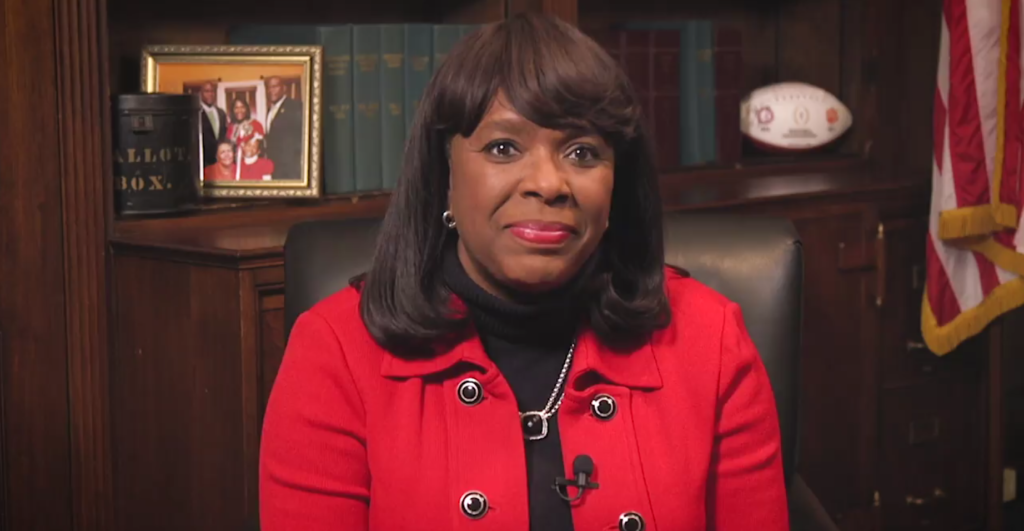

Across the bridge: Terri Sewell carries torch for voting bill

Growing up in the civil rights epicenter of Selma, Alabama, Terri Sewell heard all the stories. About the police violence during the “Bloody Sunday” march at the Edmund Pettus Bridge. About the beating of the young man who went on to become Rep. John Lewis. About the blood that was shed and the lives undone to ensure Black people would finally have the right to vote when the Voting Rights Act of 1965 became law. As she set out for the Ivy League, law school, and eventually Congress, Sewell focused on the civil rights battles to come. Income inequality, she thought, would be her work for the new era. Then the Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act. And the fight of her parents’ and teachers’ and neighbors’ generation suddenly became her own. “Never in a million years did I think that I — 57 years later — would have the cause for which John Lewis and those foot soldiers marched become my cause, too,” Sewell said in an interview. “We fought that. They were bludgeoned on a bridge for the right to vote — the equal right of every American to vote,” she said. “But so it is.” The Democratic congresswoman’s journey from rural Selma to the halls of Congress offers a vivid portrait of the nation’s progress toward ending voter discrimination, but also of accumulating setbacks in the long campaign for voting rights. Her work trying to restore the Voting Rights Act is testing the resolve of a nation that celebrates its civil rights heroes of the past but cannot muster support in Congress to update what has historically been a popular, bipartisan law. Since the Supreme Court in 2013 struck down part of the law, many states free from federal oversight have been imposing new rules, changing polling times, and even installing limits on handing out water for those waiting in line — changes that voter advocates say could make it more difficult to cast ballots in this year’s elections. Wade Henderson, interim president of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, said of Sewell: “She’s emerged as someone who is uniquely qualified to play the role that history seems to have given her.” Elected in 2010 as the first Black congresswoman from Alabama, Sewell arrived at the Capitol about as backbench as it gets, among a new handful of Democrats in a Republican tea party wave. That was a tough start for the first Black valedictorian at Selma High School and someone who can boast of attending college with both Obamas, Michelle Obama at Princeton, and the future president at Harvard Law. Coming from a long line of “preachers and teachers,” she confides she really wanted to be an actor but recalled her late father’s admonitions: “We’re not eating cornflakes for dinner for you to be majoring in theater at Princeton University.” Her family’s church in Selma was the historic Brown Chapel AME Church, the starting point for the historic voting rights marches and the place that Lewis — the future congressman, who died in 2020 — and others would return years later to commemorate “Bloody Sunday.” Her mother was the city’s first Black city councilwoman. “For me, growing up in Selma, Alabama, I didn’t have to read in the history books about these amazing foot soldiers,” said Sewell, who is 57. Many of them were “ordinary Alabamians,” she said, and once the marches were over, and the voting rights bill became law, “They went on with their lives, and many of them were my neighbors and my church members.” In Congress, Sewell put her public finance law background to work trying to preserve the historic civil rights sites in her district, which stretches across the state’s Black Belt to her current home in Birmingham. One bill she steered into law awarded the Congressional Gold Medal to the four Black girls killed in the 1963 bombing at the city’s 16th Street Baptist Church. The region has been so underserved that when “Selma” the movie opened in 2014, her mom pointed out there was no movie theater open in town for a screening. Residential yard sewage remains a stubborn problem because of lagging public investment in wastewater systems. “We can’t just come to Selma and walk across that bridge and keep on walking,” she said ahead of next month’s anniversary of the marches. “It’s a city that is dying on the vine, a city that needs economic revitalization.” Two years after Sewell took office, the Supreme Court’s stunning decision to reject the Voting Rights Act’s “preclearance” formula governing state election changes thrust the congresswoman to the forefront alongside Lewis to try to salvage the law, which had been seen as among the most enduring achievements of the Civil Rights era. Since the court’s decision, every session of Congress, she has introduced legislation, now called the John R. Lewis Voting Advancement Act. It failed in the Senate in January, part of a broader bill halted by a Republican filibuster and two Democrats unwilling to change the rules for passage. For Sewell, it was a reminder of how the battle of the earlier civil rights generation has swiftly, intractably become her own. “That’s very much part of the experience of Black leaders,” said Sherrilyn Ifill, the president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. “If you are a Black person in leadership, and you care about and love your community, the circumstances in which Black people live in this country will compel you, sooner or later … to become a civil rights activist.” Alabama is again at the center of the nation’s voting rights debate. Shelby County, not far from Selma, brought the court case in which Chief Justice John Roberts writing for the conservative majority, argued, “Our country has changed in the past 50 years.” The Roberts court will hear another Alabama case, expected later this year. The state, where one in four voters is Black, is asking the high court to reject the creation of a second, mostly Black congressional seat, despite a lower court’s finding that having just

University of Alabama to remove KKK leader’s name from hall

University of Alabama trustees voted Friday to strip the name of a one-time governor who led the Ku Klux Klan from a campus building and rename it solely for the school’s first Black student. The unanimous vote reversed a decision last week to add the name of Autherine Lucy Foster, who briefing attended the all-white state school in 1956, to a building honoring Bibb Graves, a progressive, pro-education governor who also ran a Montgomery KKK group a century ago. Rather than Lucy-Graves Hall, the classroom building will be known as Autherine Lucy Hall, trustees decided. “It’s never too late to make the right decision,” said John England, a former trustee who led a committee that initially recommended the joint name and then reversed itself after criticism that Graves didn’t deserve to have his name alongside that of Lucy, now 92 and living in metro Birmingham. Trustees didn’t mention the topic of Graves’ leadership in the notorious hate group during an online meeting, but England said some questioned why the woman’s married name of “Foster” wouldn’t be on the structure. Foster’s family wanted to use her maiden name since she was known as Autherine Lucy while originally on campus, said Chancellor Finis St. John. Foster had expressed ambivalence about being honored alongside Graves, saying she didn’t know much about him or seek out the recognition but would accept it. Foster briefly attended classes in Graves Hall but was expelled after three days when her presence brought protests by whites and threats. Foster was awarded an honorary doctorate in 2019 by the university, where she had returned and earned a master’s degree in education in 1992. Explaining the original reasoning for proposing Lucy-Graves Hall, England said committee members hoped that having a building named for both Graves and Foster would “generate educational moments that can help us learn from our conflicts and rich history.” While the main intent was meant to honor Foster, that “sort of took the background” after the decision, he said. “That’s not what we wanted,” he said. The student newspaper was among those complaining about the inappropriateness of retaining the name of a Klan leader on a campus building. Several Alabama universities have removed Graves’ name from buildings in recent years as the nation reconsidered its history and white supremacy. Troy University renamed its Bibb Graves Hall for the late Rep. John Lewis, who was denied admission there in 1957 and led voting rights marchers in Selma in 1965. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

University of Alabama revisits pairing KKK leader and Black student names

The University of Alabama is reconsidering its decision last week to retain the name of a one-time governor who led the Ku Klux Klan on a campus building while adding the name of the school’s first Black student. Trustees will meet publicly in a live-streamed video conference on Friday to revisit their decision to keep the name of former Alabama Gov. Bibb Graves on a three-story hall while renaming it Lucy-Graves Hall to also honor Autherine Lucy Foster, the University of Alabama System said. The decision to honor Foster alongside a one-time KKK grand cyclops was criticized harshly by some. An editorial in the student newspaper said Graves’ name doesn’t belong beside Lucy’s, given his association with the violent, racist organization. Foster herself expressed ambivalence, telling WIAT-TV she didn’t know much about Graves, who was considered a progressive, pro-education governor in the 1930s, despite having led the Klan in Montgomery during a period when it was at its strongest. “I wouldn’t say it doesn’t bother me, but I accept it because I didn’t ask for it, and I didn’t know they were doing it until I was approached the latter part of last year,” said Foster, 92. The committee that recommended honoring both people together “acknowledges the complexity of this amended name,” the university said. “The board’s priority is to honor Dr. Autherine Lucy Foster, who, as the first African American student to attend the University of Alabama, opened the door for students of all races to achieve their dreams at the university. Unfortunately, the complex legacy of Governor Graves has distracted from that important priority,” it said. Foster, who lives in metro Birmingham, briefly attended classes in Graves Hall after enrolling at all-white Alabama in 1956 but was expelled three days later after her presence brought protests and threats against her life. In 2019, she was awarded an honorary doctorate by the university, where she had returned and earned a master’s degree in education in 1992. The university also recognized Foster in 2017 with a historic marker in front of Graves Hall, which houses the college of education. It named a clock tower after Foster, and she’s a member of the university’s student hall of fame. Graves, who began the first of two terms as governor in 1927, left the KKK in the late 1920s, after multiple terms in the legislature. As a member of the House, he opposed the ratification of Alabama’s 1901 Constitution, which was meant to ensure white supremacy in the state and remains in effect today although heavily amended. Several state universities have stripped Graves’ name from buildings in recent years as the nation reconsidered its past. Troy University renamed its Bibb Graves Hall for the late Rep. John Lewis, who was denied admission there in 1957 and led voting rights marchers in Selma in 1965. John England Jr., a former Alabama trustee who is Black, served as chairman of the naming committee. He previously said the members wrestled with what to do about Graves’ name. “Some say he did more to directly benefit African American Alabamians than any other governor through his reform. Unfortunately, that same Gov. Graves was associated with the Ku Klux Klan. Not just associated with the Ku Klux Klan, but a Grand Cyclops – It’s hard for me to even say those words,” he said. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Bill seeks higher fines for taking down Confederate statues

A legislative committee advanced a proposal Tuesday to increase the fines on cities that take down Confederate monuments in Alabama. The Senate Governmental Affairs Committee advanced a bill by Republican Sen. Gerald Allen of Tuscaloosa that would increase the fine for violating the Alabama Memorial Preservation Act, which prohibits the removal and renaming of monuments and memorials that have stood for at least 40 years. The bill would increase the fine from a $25,000 one-time fee to a $5,000 per day fine that would accumulate until the monument is replaced. Allen said he believed the heftier fine would serve as a deterrent. Some Alabama cities have opted to pay the current $25,000 fine as part of the cost of taking down a Confederate monument “The fine will stay there until the monument, statue, street sign — whatever it may be — is replaced,” Allen told the committee. Sen. Linda Coleman-Madison, a Democrat from Birmingham, said she believed the $5,000 daily fine was excessive, particularly for smaller cities. “You are going up and up and up and up, and now you are in the punitive stage,” Coleman-Madison said of the total fines a city could face. While the Alabama Memorial Preservation Act does not mention Confederate monuments, it was enacted as some Southern states and cities began removing monuments and emblems of the Confederacy. Birmingham and several other cities have been fined under the law for taking down Confederate monuments. Most recently, the Alabama attorney general’s office told Montgomery officials that the city faces a $25,000 fine for renaming Jeff Davis Avenue for Fred Gray, a famed civil rights attorney who represented Rosa Parks and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. The bill also calls for the Alabama Historical Commission to design, construct and place a statue of the late civil rights leader John Lewis by the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma. Lewis, a native of Alabama who became a long-serving Georgia congressman, was beaten by state troopers on the bridge in a melee known as Bloody Sunday. The committee also advanced a bill that would make it a felony offense, punishable by up to 20 years in prison, to damage a historic monument while “participating in a riot, aggravated riot, or unlawful assembly.” Both bills now move to the full Alabama Senate. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Terri Sewell gets no support from delegation on Voting Rights Act

Reps. Mo Brooks and Barry Moore vowed to vote against H.R. 4, the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. Introduced by Alabama’s own Terri Sewell, the Act passed the House yesterday with no Republican support. Alabama Congressmen all voted Nay, except for Sewell. The bill now moves to the Senate, where it’s unlikely to pass. Democrats do not have enough votes to overcome the opposition from Senate Republicans who claim the bill is “unnecessary.” The bill seeks to restore a key provision of the federal law that compelled states with a history of discrimination to undergo a federal review of changes to voting and elections. The Supreme Court set aside the formula that decided which jurisdictions were subject to the requirement in a 2013 decision and weakened the law further in a ruling this summer, reported the Associated Press. In a press release, Brooks stated, “The Socialist Democrats were dealt a blow when the Senate voted down H.R 1, the ‘Socialist Democrat Election Fraud Enhancement Act.’ Now, they seek to again undermine America’s election systems with H.R. 4, a bill that eliminates state safeguards that protect honest and accurate elections.” On Twitter, Brooks commented, “I will vote against H.R. 4 because much like H.R. 1, it undermines America’s Republic and effectively turns our election results into what we so often see in North Korea, the old Soviet Union, Venezuela and any number of other pretend republics.” Rep. Moore said in a press release, “After failing to federalize our elections through H.R. 1, Pelosi’s deceitful sequel is yet another unconstitutional power grab intended to keep Democrats in power. Despite being named after a Civil Rights icon, the title only serves as a guise to hide Democrats’ true intentions of centralizing election power with the federal government. I cannot support this delusional attack on democracy, but I remain committed to strengthening election integrity for all Americans.” Sewell commented on Twitter, “This is my fourth time introducing a version of the Voting Rights Advancement Act but my first time doing it without John. As I cast my vote for #HR4 later today, I’ll be thinking of John. I know he’ll be watching over us as we get into #GoodTrouble and carry on his legacy.” On Wednesday, Brooks posted on Twitter, “Socialist Democrats seek to undermine America’s election systems with HR4, a bill that eliminates state safeguards that protect honest and accurate elections. I’m glad to stand with @RepBarryMoore and the rest of the Alabama delegation in opposing it.”

House passes bill bolstering landmark voting law

House Democrats have passed legislation that would strengthen a landmark civil rights-era voting law weakened by the Supreme Court over the past decade, a step party leaders tout as progress in their quest to fight back against voting restrictions advanced in Republican-led states. The bill, which is part of a broader Democratic effort to enact a sweeping overhaul of elections, was approved on a 219-212 vote, with no Republican support. Its Tuesday passage was praised by President Joe Biden, who said it would protect a “sacred right” and called on the Senate to “send this important bill to my desk.” But the measure faces dim prospects in that chamber, where Democrats do not have enough votes to overcome opposition from Senate Republicans, who have rejected the bill as “unnecessary” and a Democratic “power grab.” That bottleneck puts Democrats right back where they started with a slim chance of enacting any voting legislation before the 2022 midterm elections when some in the party fear new GOP laws will make it harder for many Americans to vote. But they still intend to try. Speaking from the House floor, Speaker Nancy Pelosi said it was imperative for Congress to counteract the Republican efforts, which she characterized as “dangerous” and “anti-democratic.” “Democracy is under attack from what is the worst voter suppression campaign in America since Jim Crow,” Pelosi said. The John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, named for the late Georgia congressman who made the issue a defining one of his career, would restore voting rights protections that have been dismantled by the Supreme Court. Under the proposal, the Justice Department would again police new changes to voting laws in states that have racked up a series of “violations,” drawing them into a mandatory review process known as “preclearance.” The practice was first put in place under the Voting Rights Act of 1965. But it was struck down by a conservative majority on the Supreme Court in 2013, which ruled the formula for determining which states needed their laws reviewed was outdated and unfairly punitive. The court did, however, say that Congress could come up with a new formula, which is what the bill does. A second ruling from the court in July made it more difficult to challenge voting restrictions in court under another section of the law. The bill’s sponsor, Rep. Terri Sewell, said “old battles have indeed become new again,” enabled by the Supreme Court’s rulings. “While literacy tests and poll taxes no longer exist, certain states and local jurisdictions have passed laws that are modern-day barriers to voting,” said Sewell, an Alabama Democrat. In many cases, the new bill wouldn’t apply to laws enacted in the years since the court’s 2013 ruling. That likely includes the wave of new Republican-backed restrictions inspired by Donald Trump’s false claims of a stolen 2020 election. But if signed into law along with Democrats’ other election bill, the For the People Act, many of those restrictions could be neutralized — and likely prevented from getting approved again. Both laws would likely face legal challenges. In the short term, the vote Tuesday was expected to soothe restive Democratic activists who have been frustrated by inaction on the issue in the Senate. NAACP President Derrick Johnson said he was “encouraged” by the bill’s passage. But he also offered a thinly veiled threat, pledging to watch closely as the Senate takes it up and “keep track of every yea and every nay” vote. “Make no mistake, we will be there, on the ground in 2022, in every state that needs a new Senator,” he said in a statement. Democrats’ slim 50-50 majority in the Senate means they lack the 60 votes needed to overcome a filibuster. For months, progressives have called for scrapping the filibuster, but a number of moderate Democrats oppose the idea, denying the votes needed to do so. It’s also not clear that the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, as written, would be supported by all Democrats in the Senate, where there are no votes to spare. One provision in the bill would ban many types of voter ID laws, including those already on the books. That’s at odds with a proposal from West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin, who is the chamber’s most conservative Democrat. He’s spent weeks working with Senate leadership to develop a more narrowly focused alternative to the For the People Act and has specifically called for a voter ID standard that would allow for people to use a document like a utility bill. Republicans, meanwhile, blasted the timing of the measure, noting that Pelosi called Democrats back from August recess to pass the bill, as well as to take votes on Democrats’ spending priorities when the U.S. is dealing with its chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan. “If there’s any moment in time to put an election aside, if there’s any moment of time to put politics aside, I would have thought today was this day,” said House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy. Conservatives also criticized the bill as a departure from the 1965 voting law, which used minority turnout data as well as a place’s history of enacting discriminatory voting laws when determining which places would be subject to preclearance. The new bill, instead, leans heavily on looser standards, such as using the number of legal settlements and consent decrees issued in voting rights cases to pull places into preclearance. That would, Republicans argue, play into the hands of Democrats, who have built a sophisticated and well-funded legal effort to challenge voting rules in conservative-leaning states. Rep. Michelle Fischbach, a Minnesota Republican, predicted it would be a boon for Democratic advocacy groups and trial lawyers, who would “file as many objections as possible to manufacture litigation.” “It empowers the attorney general to bully states and seek federal approval before making changes to their own voting laws,” she said. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Democrats unveil plan to update landmark voting law

House Democrats on Tuesday put forward a new proposal to update the landmark Voting Rights Act, seeking against long odds to revive the civil rights-era legislation that once served as a barrier against discriminatory voting laws. The bill, introduced by Rep. Terri Sewell of Alabama, seeks to restore a key provision of the federal law that compelled states with a history of discrimination to undergo a federal review of changes to voting and elections. The Supreme Court set aside the formula that decided which jurisdictions were subject to the requirement in a 2013 decision and weakened the law further in a ruling this summer. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., pledged to move quickly and said Democrats plan to pass the bill when the House returns next week. “With the attack on the franchise escalating and states beginning the process of redistricting, we must act,” Pelosi said in a statement. The push comes at a time when a number of Republican-led states have passed laws tightening rules around voting, particularly mail ballots. Democrats have sounded the alarm about the new hurdles to voting, comparing the impact on minorities to the disenfranchisement of Jim Crow laws, but they have struggled to unite behind a strategy to overcome near-unanimous Republican opposition in the Senate. The new House bill, known as H.R. 4, is named after Georgia congressman and civil rights leader John Lewis, who died last year. Sewell announced the introduction of the bill in front of the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, where Lewis was beaten during a civil rights march in 1965. The Voting Rights Act was signed into law a few months later. “We’re not looking to punish or penalize anyone. This is about restoring equal access to the ballot box. It’s about ensuring that Americans know their vote counts and their vote will count at the ballot box,” Sewell said. The Lewis bill outlines a new, expanded formula that the Department of Justice can use to identify discriminatory voting patterns in states and local jurisdictions. Those entities would then need to get DOJ approval before making further changes to elections. The bill also includes a provision designed to counter the summer’s Supreme Court ruling that made it harder to challenge potentially discriminatory voting changes. A companion bill pushed by Democrats, known as the For the People Act, has stalled in the Senate amid Republican opposition and disagreement among Democrats about whether to change procedural rules in the evenly divided Senate to get it passed. Democrats have argued both bills are needed to safeguard access to the ballot. They emphasize that the update to the Voting Rights Act would not apply to many voting changes already made by the states. The For the People Act, on the other hand, would create minimum voting standards in the U.S., such as same-day and automatic voter registration, early voting, and no-excuse absentee voting. The bill would also change various campaign finance and ethics laws. Senate Democrats have pledged to take up that more expansive bill when they return next month as the first order of business, though it is unclear how they can maneuver around GOP opposition. Republicans signaled they’ll try to stop the John Lewis Act much as they have the For the People Act. “This bill is a federal power grab and a gift to partisan, frivolous litigators who will use it to manipulate state laws and throw all federal elections into chaos, further undermining voter confidence in fair and accurate elections,” said Jason Snead, executive director of Honest Elections Project Action, a conservative advocacy group. Voting rights groups have been putting pressure on Democrats to eliminate or change the filibuster rules in the Senate, which requires 60 votes to proceed with most legislation, to get around the broad GOP opposition to the bills. That partisan opposition leaves Democrats well short of the needed support to advance them in the 50-50 Senate. At least two Democratic senators, Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona and Joe Manchin of West Virginia, have said they oppose eliminating the filibuster though discussions are ongoing about potential changes to the rules. Groups that back the voting measures are planning marches in several cities on Aug. 28 to call on the Senate to remove the filibuster rule. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Joe Biden marks ‘Bloody Sunday’ by signing voting rights order

A new executive order from President Joe Biden directs federal agencies to take a series of steps to promote voting access, a move that comes as congressional Democrats press for a sweeping voting and elections bill to counter efforts to restrict voting access. His plan was announced during a recorded address on the 56th commemoration of “Bloody Sunday,” the 1965 incident in which some 600 civil rights activists were viciously beaten by state troopers as they tried to march for voting rights in Selma, Alabama. “Every eligible voter should be able to vote and have it counted,” Biden said in his remarks to Sunday’s Martin and Coretta King Unity Breakfast before signing the order. “If you have the best ideas, you have nothing to hide. Let the people vote.” Biden’s order includes several modest provisions. It directs federal agencies to expand access to voter registration and election information, calls on the heads of agencies to come up with plans to give federal employees time off to vote or volunteer as nonpartisan poll workers, and pushes an overhaul of the government’s Vote.gov website. Democrats are attempting to solidify support for House Resolution 1, which touches on virtually every aspect of the electoral process. It was approved Wednesday on a near party-line vote, 220-210. The voting rights bill includes provisions to restrict partisan gerrymandering of congressional districts, strike down hurdles to voting and bring transparency to a murky campaign finance system that allows wealthy donors to anonymously bankroll political causes. Democrats say the bill will help stifle voter suppression attempts, while Republicans have cast the bill as unwanted federal interference in states’ authority to conduct their own elections. The bill’s fate is far from certain in the closely divided Senate. Conservative groups have undertaken a $5 million campaign to try persuade moderate Senate Democrats to oppose rule changes needed to pass the measure. With his executive order, Biden is looking to turn the spotlight on the issue and is using the somber commemoration of Bloody Sunday to make the case that much is at stake. Bloody Sunday proved to be a turning point in the civil rights movement that led to passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Similarly, Biden is hoping the Jan. 6 sacking of the U.S. Capitol by a pro-Donald Trump mob will prove to be a clarion call for Congress to take action to improve voter protections. “In 2020 — with our very democracy on the line — even in the midst of a pandemic – more Americans voted than ever before,” Biden said. “Yet instead of celebrating this powerful demonstration of voting — we saw an unprecedented insurrection on our Capitol and a brutal attack on our democracy on January 6th. A never-before-seen effort to ignore, undermine and undo the will of the people.” Biden’s also paid tribute to the late civil rights giants Rev. C.T. Vivian, Rev. Joseph Lowery and Rep. John Lewis. All played critical roles in the 1965 organizing efforts in Selma and all died in within the past year. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Alabama university removes Wallace name from building

The University of Alabama at Birmingham has removed the name of four-term governor and presidential candidate George C. Wallace from a campus building over his support of racial segregation. A resolution unanimously approved by trustees Friday said Wallace rose to power by defending racial separation and stoking racial animosity. While noting Wallace’s eventual renouncement of racist policies, the resolution said his name remains a symbol of racial injustice for many. A UAB building that was named after Wallace in 1975 will now be called simply the Physical Education Building. Removing Wallace’s name from the structure “is simply the right things to do,” trustee John England Jr. said in a statement. Wallace vowed “segregation forever” at his 1963 inaugural and was paralyzed in an assassination attempt while running for president in 1972. He has a “complex legacy” that includes his apology to the late Rep. John Lewis, who was beaten by Alabama state troopers while trying to march for voting rights in Selma, England said. “That said, his stated regret late in life did not erase the effects of the divisiveness that continue to haunt the conscience and reputation of our state,” he said. Wallace was elected to his fourth term as governor in 1982 with support from Black voters and died in 1998. Multiple buildings around the state bear his name. An online petition urged Auburn University to rename a building honoring Wallace last year as protests against police killings and racial injustice swept across the nation, but no action was taken. Wallace’s son George Wallace Jr. wrote an open letter opposing such a move, which he said would fail to recognize his change late in life. Wallace’s daughter Peggy Wallace Kennedy, in a statement released by UAB, expressed support for change on the Birmingham campus. “It is important to the university to always seek positive and meaningful change for the betterment of students, faculty, and the community,” she said. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Steve Flowers: We lost some good ones this year

As is my annual ritual, my yearend column pays tribute to Alabama political legends who have passed away during the year. Sonny Cauthen passed away in Montgomery at age 70. He was the ultimate inside man in Alabama politics. Sonny was a lobbyist before lobbying was a business. He kept his cards close to his vest, and you never knew what he was doing. Sonny was the ultimate optimist who knew what needed to be achieved and found like-minded allies with whom to work. When he had something to get done, he bulldozed ahead and achieved his mission. Sonny was a yellow dog Democrat who believed in equal treatment and rewarding hard work. He was an avid outdoorsman and hunter and mentored a good many young men in Montgomery. Another Montgomerian who will never be forgotten was Representative Alvin Holmes, who passed away at 81. Like Sonny, Alvin was born and raised and lived his entire life in his hometown of Montgomery. He, too, was a real Democrat and an icon in Alabama politics. Alvin represented the people of Montgomery for 44-years in the Alabama House of Representatives. He was one of the most dynamic and outspoken legislators in Alabama history, as well as one of the longest-serving members. I had the opportunity to serve with Alvin for close to two decades in the legislature. We shared a common interest in Alabama political history. In fact, Alvin taught history at Alabama State University for a long time. He was always mindful of the needs of his district, as well as black citizens throughout the state. Alvin was one of the first Civil Rights leaders in Montgomery and Alabama. He helped organize the Alabama Democratic Conference and was Joe Reed’s chief lieutenant for years. Ironically, we lost another Civil Rights icon this year. John Lewis was born in rural Pike County in the community of Banks. After graduating from college, John joined the Dr. Martin Luther King as a soldier in the army for Civil Rights. John was beaten by Alabama State Troopers near the Edmund Pettus Bridge on the infamous Bloody Sunday Selma to Montgomery march. He became a Civil Rights legend in America. He was one of Dr. King’s closest allies. John became almost as renowned worldwide as a Civil Rights leader as Dr. King. John moved to Atlanta with Dr. King and was elected to the U.S. Congress from Atlanta and served 33 years with distinction. Even though John was a national celebrity, he would take time out of his busy schedule to drive from Atlanta to rural Pike County to go to church with his mother at her beloved Antioch Baptist Church. John died of pancreatic cancer in July at age 80. Another Alabama political legend, John Dorrill, passed away in January at age 90. Ironically, John Dorrill and John Lewis were both born and raised in rural Pike County near Troy. John Dorrill went to work for the powerful Alabama Farmers Federation shortly after graduating from Auburn. He worked for the Federation for 43 years. For the last 20 years of his career, he oversaw and was the mastermind of their political plans and operations as Executive Director of the Federation. He retired and lived out his final years on his ancestral home place in Pike County. John Dorrill was one of my political mentors and friends. Another Montgomery political icon, former Republican State Senator Larry Dixon, passed away only a few weeks ago from COVID-19 complications at age 78. He served over 20 years in the state legislature. Larry epitomized the conservative Republican, and his voting record was right in line with his Montgomery constituency. He was known as “Montgomery’s State Senator,” but his ultimate legacy may be as a great family man. Larry was a devoted husband to his wife, Gaynell, and father to his two daughters. Larry was a good man. Former Alabama Supreme Court Judge Hugh Maddox recently passed away at age 90. Judge Maddox served 31 years on the Alabama Supreme Court before his retirement in 2001. One of my favorite fellow legislators and friends, Representative Richard Laird of Roanoke, passed away last week from COVID-19. He was 81 and served 36 years in the Alabama House of Representatives. Richard was a great man and very conservative legislator. In addition to Richard Laird, Alvin Holmes, and Larry Dixon, several other veteran Alabama legislators passed away this year, including Ron Johnson, Jack Page, and James Thomas. We lost some good ones this year, who will definitely be missed as we head into 2021. Happy New Year. Steve Flowers is Alabama’s leading political columnist. His weekly column appears in over 60 Alabama newspapers. He served 16 years in the state legislature. Steve may be reached at www.steveflowers.us.

Pandemic deaths and economic fallout are top Alabama story

A biological threat that once seemed far removed from Alabama dominated both state news and everyday life like nothing else in 2020. The coronavirus pandemic was the state’s top news story of the year, and its effects will linger into the New Year and beyond. Here is a look at that and other Top 10 Alabama news stories of the year: CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC A pandemic that spread waves of death and misery across the globe killed more than 4,100 people in Alabama, sickened thousands more and ravaged the state’s economy like nothing else in decades. A springtime of school closings and business shutdowns was followed by months of mask-wearing and social distancing. A midsummer surge in cases eased, but that was followed by a fall spike that health experts say will keep killing people at least into 2021. Unemployment dropped after hitting a high of 12.9% in April, when nearly 217,000 people lost their jobs statewide. Yet the prospects for continuing improvement could be tied to how well people heed health precautions and the success of a vaccination program that is just beginning. SENATE ELECTION Republican Tommy Tuberville reasserted the GOP’s lock grip on Alabama by defeating Democratic Sen. Doug Jones after stopping a comeback bid by Jeff Sessions for the party’s nomination. Faced with a crowded primary field that included President Donald Trump’s first attorney general, the retired football coach emerged from a runoff against Sessions to run a campaign that consisted of embracing Trump at all turns. The tactic worked to perfection in deeply conservative Alabama: Tuberville trounced Jones in November to oust the only state Democrat holding statewide office. RACIAL RECKONING The fallout from a police killing hundreds of miles away from Alabama helped erase vestiges of the state’s white supremacist past with stunning swiftness. Confederate monuments were removed and college buildings were renamed following the police killing of George Floyd in Minnesota. A night of violence after a demonstration in Birmingham set the stage for the removal of an obelisk honoring Confederate soldiers and sailors. Monuments also came down in Mobile, Montgomery, and Huntsville, and protests were held elsewhere. The Alabama Department of Archives and History acknowledged its past role in perpetuating racism and so-called lost cause ideals in a sign of systemic change that once seemed unlikely. ALABAMA PRISONS Longstanding complaints over violence, dilapidated buildings, and inadequate care in Alabama’s prisons resulted in a Justice Department lawsuit claiming men’s lockups are so bad they violate the constitutional ban on cruel and unusual punishment. Calling the state’s prison system one of the most understaffed and violent in the nation, the department asked a court to require unspecified changes to improve conditions. The court fight will last at least into 2021, as Alabama said it plans a vigorous defense in court. The state also is moving ahead with a $900 million plan to have companies build three new, giant prisons that will be leased by Corrections. TROPICAL WEATHER Hurricane Sally blasted the Alabama coast, leaving widespread damage and knocking out power for weeks in some areas, during a record-setting year of tropical weather. Sally made landfall as a Category 2 storm at Gulf Shores on Sept. 16, pummeling the coast with fierce winds and as much as 30 inches (76 centimeters) of rain. Officials said the damage was worse in places than from Hurricane Ivan, which landed a direct hit on the same area in 2004. Crews spent weeks removing mountains of debris that lined roadsides. The hurricane season was so busy forecasters had to turn to the Greek alphabet after running out of assigned names. JOHN LEWIS Alabama native and longtime U.S. Rep. John Lewis was honored with events in Troy, Selma, and Montgomery following his death at age 80 in July. A wagon drawn by two horses carried Lewis’ body across Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge, where he and other voting rights marchers were attacked by Alabama state troopers in 1965. A long line of people later waited to pay respects to Lewis as he was honored at Alabama’s Capitol. A native of rural Pike County near Troy, Lewis had moved to Georgia and represented Atlanta in Congress for decades. DEADLY MARINA FIRE Eight people were killed in a horrific fire that swept through a north Alabama marina near the Tennessee River in Scottsboro. The January blaze at Jackson County Park Marina began in the middle of the night and quickly engulfed a dock where people who lived aboard boats were sleeping. Five children and teens were among the dead, and the victims included six members of one family. The fire was later determined to be an accident, but a federal report said it was worsened by the marina’s “limited fire safety practices.” HUBBARD REPORTS TO PRISON The long saga of disgraced Alabama House Speaker Mike Hubbard finally ended behind bars. The one-time Republican leader reported to prison in September four years after jurors convicted him of ethics violations. Then a judge reduced Hubbard’s sentence from four years to 28 months at the request of the defense after part of his conviction was overturned earlier this year. Prosecutors accused Hubbard of leveraging his powerful Statehouse office to obtain clients and investments for his private businesses, and he was automatically removed from office when he was found guilty in 2016. Six of his 12 felony convictions were thrown out on appeal. DEMOCRATIC FIGHT A lawsuit for control of the Alabama Democratic Party ended with new leadership but the same old results. Long given up for dead in a reliably red state, the party found itself at the center of a court fight over control of the organization in late 2019. The battle ended in February when a judge dismissed the lawsuit filed by longtime leader Nancy Worley to prevent the new party chair, state Rep. Chris England, from taking control. Newly invigorated, the party fielded a slate of candidates with hopes of winning new seats in the November election. Instead, Democrats didn’t claim any new statewide offices and lost the one they had when Sen. Doug Jones lost to Republican Tommy Tuberville. CLOTILDA The state committed to spend $1 million to preserve the