Unpopular GOP candidates mulling when to pack it in

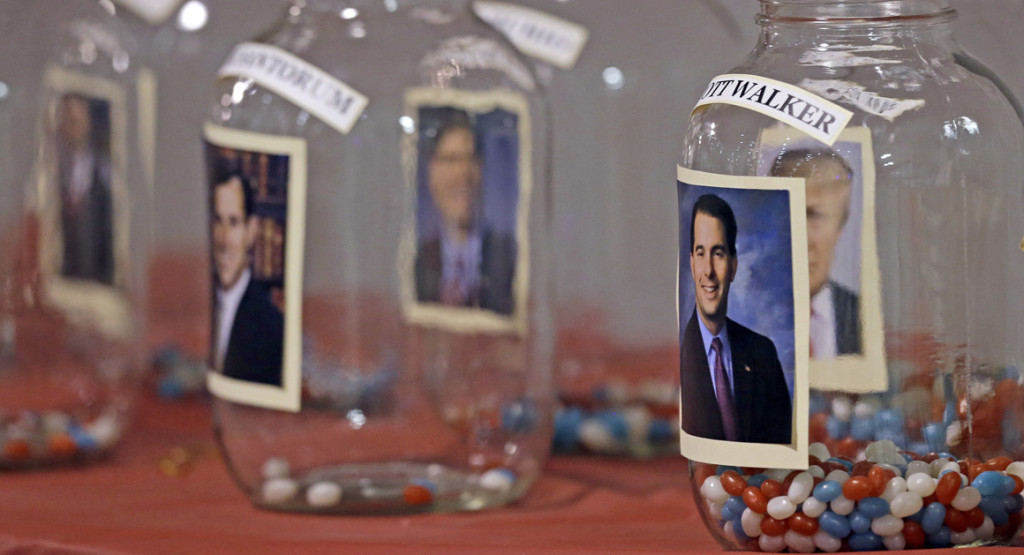

For months, Republican presidential candidates with dwindling bank accounts and negligible support in polls have been finding reasons to stay in the 2016 race. Now, a few must weigh whether they can keep competing after being downgraded or excluded from Tuesday’s fourth GOP debate. New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie and former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee have been bumped to the undercard debate because of low poll numbers, while South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham and former New York Gov. George Pataki didn’t qualify for either event. Each of the candidates has so far vowed to stay in the race, keeping the Republican contest crowded with just under three months until the Iowa caucuses kick off the nominating process. Fifteen Republicans are still running for president, while three Democrats are vying for their party’s nomination. “I’ll go there, debate, and as soon as I leave the debate I’ll go to Iowa and get back to work,” Christie said Friday as he filed his paperwork to run in the New Hampshire primary. Struggling candidates can see multiple reasons to keep their White House hopes alive. It’s relatively inexpensive to campaign in Iowa and they can use television appearances as a way to get free publicity. Running for president can be a stepping stone to high-profile television jobs and other lucrative opportunities. And given that the field remains unsettled, there’s always the possibility that an unlikely candidate can make a late surge in one of the early voting states. Huckabee pulled off a surprise victory in the 2008 Iowa caucuses, and former Pennsylvania Sen. Rick Santorum did the same four years later, though neither ultimately secured his party’s nomination. “Candidates never really run out of reasons to run,” said Kevin Madden, a Republican strategist who advised 2012 GOP nominee Mitt Romney. “Many are staying in because the lesson learned from past campaigns is that it’s possible to go from 1 percent to winning the caucuses, or at least beat expectations.” Yet some Republicans are concerned, believing that one of the reasons the race remains unsettled is because there are still so many candidates. Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker openly worried about that when he abruptly ended his campaign in late September amid a cash shortage. He encouraged other candidates to follow his lead “so voters can focus on a limited number of candidates who can offer a positive conservative alternative to the current front-runner.” The front-runner Walker was referring to was Donald Trump. The billionaire real estate mogul is still atop the GOP field, causing heartburn for establishment Republicans who fear he couldn’t win in the general election — or that his controversial statements on immigration and minorities could hurt the party even if he’s not the nominee. In his typical no-holds-barred style, Trump has been calling out rivals who are struggling and pointing them toward the exits. “There are too many people,” Trump said this week. “If a person has been campaigning for four or five months and they’re at zero or 1 or 2 percent, they should get out.” Other candidates have avoided assessing when their rivals should end their campaigns, a process that is often emotional and deeply personal. But for weeks, Jeb Bush supporters have said the crowded field is contributing to the former Florida governor’s struggle to gain traction. “For Jeb, the field’s got to get narrowed down a lot to shine,” said Philip Taub, a supporter from New Hampshire. Iowa State Rep. Ron Jorgenson said Bush is “suffering just from a lot of fragmentation with so many people in the race.” The New York Times, in a biting editorial, has called for Christie to end his campaign and refocus on his duties as governor. “You are accountable for what happens in New Jersey,” the paper wrote last week. And in Louisiana, Gov. Bobby Jindal‘s pursuit of the presidency has led both Democrats and Republicans in the state to criticize him for being an absentee state executive. Jindal, whose term as governor ends in January, has spent most of the last several months campaigning across Iowa. “I think spending time here, working here is paying off,” the low-polling Jindal said. He is facing a major cash crunch, ending the last fundraising quarter with $261,000 on hand. But his financial disclosure forms show he’s finding ways to campaign cheaply, bunking at affordable hotel chains. Santorum, who is also low on cash, appears to be looking around for deals on online travel sites, with multiple payments to Expedia and Hotels.com. Of course, for most candidates, there eventually comes a time where a lack of money and lack of votes becomes too great to overcome. “They need to recognize that moment and make a move,” Madden said. Republished with permission of the Associated Press.

Analysis: For Scott Walker, a cascade of troubles ends campaign

For Scott Walker, it wasn’t one thing that led to the demise of his presidential campaign. It was just about everything. Financial troubles. A bloated staff. Repeated stumbles and flip flops. A candidate that professed to be a fighter, but too often, didn’t show all that much fight. The Wisconsin governor, who dropped out of the Republican race for president on Monday after only two months as a formal candidate, did so after making a litany of mistakes and missteps that could make for a “what not to do” manual for future candidates. Walker entered the 2016 race as an ostensible Republican darling, shot into the national spotlight by his victories over unions and his triumph in a recall election. With Midwestern appeal and conservative credentials, and buoyed by a rousing performance at a Republican forum in January, he rose to the top very of early polls in Iowa. That moment in Iowa proved to be Walker’s high point. As presidential primaries so often reveal, gleaming resumes don’t equal votes or big fundraising totals. And early favorites can quickly fade. “The support he had was relatively soft,” said Republican Wisconsin state Sen. Luther Olsen. “He was at the top essentially because of one speech.” To some extent, Walker is a victim of a campaign in which voters long-frustrated with politics are turning their backs on candidates with long resumes in government. Walker insisted that he, too, would “wreak havoc” on Washington, but he was drowned out by bombastic billionaire Donald Trump. But Walker’s problems were broader than a mismatch with the electorate’s mood and were foreshadowed even during his campaign’s heady early days. On a February trade mission to Europe meant to bolster his foreign policy credentials, Walker refused to answer questions about international affairs. He also punted on a question about whether he believed in evolution. That shallow foreign policy experience and inability to deftly handle questions became more pronounced as the campaign went on. He was widely panned for arguing that his experience fighting unions in Wisconsin had prepared him for defeating the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq. He said it was “legitimate” to discuss building a wall along the U.S.-Canada border. And he gave three different answers about his position on birthright citizenship in a week. Even his efforts to separate himself from Washington fell flat. At one point, he said he isn’t a career politician – despite having held elected office for 22 straight years. “The glare of the klieg lights came early for Walker and it’s hard to be prepared for that type of scrutiny when it’s your first presidential campaign,” said Kevin Madden, who advised Mitt Romney during his second run for president in 2012. Walker also suffered from strategic and structural campaign blunders. While Iowa and its kickoff caucus gave Walker the best chance to grab an early victory, his campaign built a wide network of staff and consultants in states that don’t vote until well into March. But running a national campaign is costly, and Walker and his team burned through cash faster than they could raise it. Even as donors began to grumble about the expensive operation, Walker’s team resisted scaling back or trimming salaries. Walker’s admission last week that he was shifting course and putting “all our eggs in the basket of Iowa” was a sharp departure from his campaign’s confident predictions earlier in the year about plans to rack up delegates throughout the South and Midwest late in the primary contest. In addition to refocusing on Iowa, Walker’s campaign made a last-ditch effort to energize Republicans by reaching back to the issue that had made the governor one of his party’s brightest White House hopes. He unveiled a sweeping blueprint for upending labor unions nationwide, a plan so aggressive that it was even criticized by some Republicans. Then Walker took the stage in last week’s second Republican debate. His union plan garnered no mention from moderators or rival candidates, and Walker didn’t even bring it up himself. Walker needed a standout performance in that debate, one that would validate his assertion that he was a Washington outsider with a fighting spirit. Instead, he generated the least amount of speaking time of the 11 eleven candidates on the stage and gave middling responses when attention did turn his way. The final blow came Sunday, with the release of a new CNN/ORC poll. While polls at this early stage of the race are often fickle, the message to Walker was unmistakable, according to one campaign aide, who insisted on anonymity in order to discuss the team’s internal thinking. Walker, who had once led the GOP field, was registering less than one percent of voter support. His standing as a White House candidate had been reduced to an asterisk. Republished with permission of the Associated Press.