Alabama voter registration climbs, but turnout lags rest of nation

by Ralph Chapoco, Alabama Reflector September 15, 2023 This article is part of U.S. Democracy Day, a nationwide collaborative on Sept. 15, the International Day of Democracy, in which news organizations cover how democracy works and the threats it faces. To learn more, visit usdemocracyday.org. While Alabama has enjoyed record numbers in terms of people registering to vote, voter rights groups point to troubling signs despite those figures for voters gaining access to the ballot box to exercise their constitutional right as citizens. Alabama Secretary of State Wes Allen and his predecessor, John Merrill, have pointed to a 32% increase in voter registration in the last decade as a sign of greater interest in the process. But election turnout has lagged other states, even in presidential election years. More than 2.3 million Alabamians cast ballots in the 2020 presidential election. In terms of volume, that was a record, but it only represented 62% of Alabama voters casting votes, one of the lowest presidential turnouts in 30 years. “One of the things that we have seen, we are still seeing, is low turnout,” said Kathy Jones, president of the League of Women Voters of Alabama. “Presidential elections get high turnout, but in the elections at the local level, and during the midterms, you see pretty sad turnout. That is not good for democracy.” The reasons for the disparities have to do with culture, state laws that impede access to the ballot, and a lack of competitive elections. Allen and Merrill have turned to the public airwaves to claim credit for the number of active, and registered voters in Alabama. The state has steadily increased that number, going from about 2.8 million about a decade ago to roughly 3.3 million at the end of 2022. Through the end of August, the state’s voter rolls increased by an additional 30,000 people. Richard Fording, a professor of political science at the University of Alabama, said “the numbers aren’t bad.” But relatively few Alabamians exercise their right to vote, a continuation of a longstanding problem that has plagued the state for decades. According to data compiled by Michael McDonald, a political science professor at the University of Florida, only 37.3% of eligible voters turned out for the November 2022 elections, the fifth-worst in the United States. Mississippi, another southern state, fared the worst at 32.5%. Tennessee, West Virginia, and Indiana were the only other states with lower turnout than Alabama. The issue starts with the state’s history. “Alabama was classified as a state with a traditionalistic political culture,” Fording said. “That means a few different things, but with respect to the orientation of government participation, it is an elitist orientation.” That culture emerged from a backdrop of slavery, segregation, and disenfranchisement of large swathes of voters, mostly Blacks but also poor whites. Elites in the state maintained the status quo through literacy tests, poll taxes, and other discriminatory voting practices. Though those have been outlawed, their impact on the state’s political culture remains. “When there is a system that is the status quo, those who benefit from it want to rationalize that system, as being just,” Fording said. “And if they have the power to do that through various channels of socialization like the education system, then that is likely to become embedded somewhat permanently in the culture.” Several crosscurrents have taken shape that stem from that history that have served to depress voter turnout. “We have started out way behind,” Fording said. “And so, it is just harder to finish first when starting last.” Foregone conclusions The low turnout is not tied to a party. In the 2006 elections, when Democrats controlled the state Legislature, voter participation was 36%. Some demographic trends may play a role. Education tends to correlate with voter participation, and Alabama has a smaller percentage of college graduates than the nation as a whole. Party strength can also influence turnout. “In a large sense, there is not a lot of democracy because it is a foregone conclusion that most of the outcomes are going to be Republican,” said Thomas Shaw, an associate professor in the Department of Political Science and Criminal Justice at the University of South Alabama. The state is solid red, with the Republicans holding the governor’s office, all statewide elected positions, and the state Legislature. Democrats, once the dominant party in the state, have held onto power in the Black Belt and the state’s cities. But the state has not voted for a Democratic presidential nominee since 1976, and Democrats have won only one statewide election (the 2017 special election for U.S. Senate) since 2010. That can depress turnout. It also makes candidate recruitment difficult. The Democrats’ statewide candidates in 2022 were mostly inexperienced and underfunded. That depressed turnout to the point that normally safe Democratic legislative districts saw closer-than-expected races. “The people they put on the ballot in 2022 were no-name nobodies who got some of the least amount of support in the entire history of Democratic politics in Alabama,” said David Hughes, an associate professor of political science at Auburn University Montgomery. The state party is embroiled in a fight over its bylaws and leadership. Leaders of the party voted in May to disband three diversity caucuses and adopt new bylaws, replacing a set adopted in 2019 amid a Democratic National Committee (DNC) investigation. The DNC is investigating the May meeting. “I don’t think anybody would look at the state Democratic Party and say that it is functional,” Hughes said. All of that weighs on turnout, said Shaw. “If it is a presidential election, and you are a Democrat in Alabama, you know there is no chance that your candidate is going to get elected in Alabama; how does that make you feel about going to the polls,” he said. “It makes you feel like, ‘Why should I bother?’” Ballot access Legislators in recent years have also taken to making voting more difficult. Alabama does not have early voting or no-excuse absentee voting. The

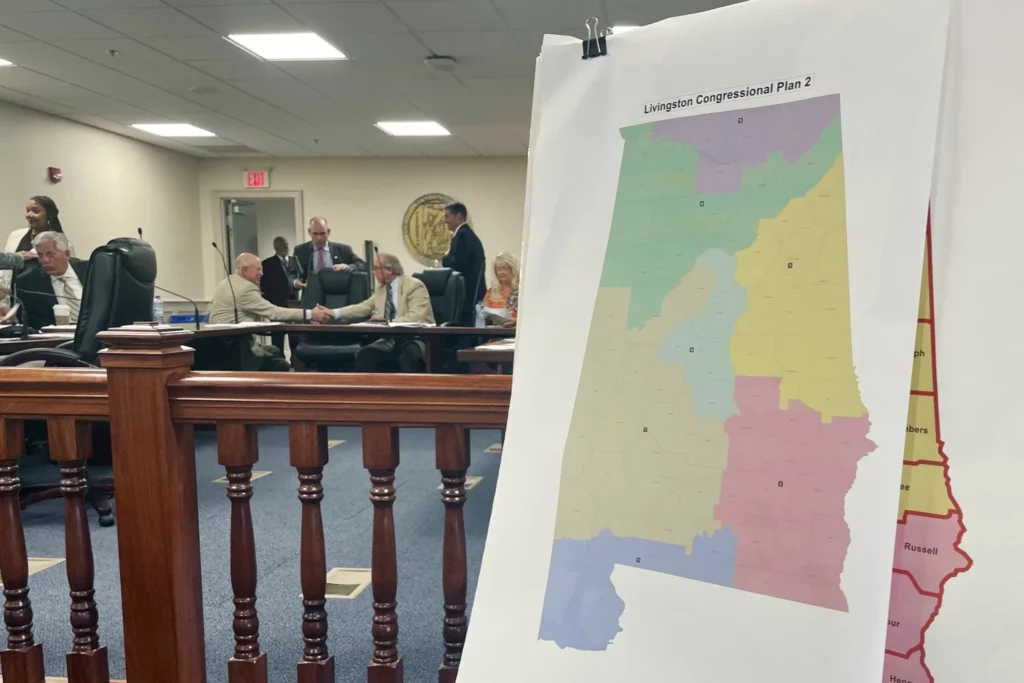

Legal fights over voting districts could play role in control of Congress for 2024

Democrats got a potential boost for the 2024 congressional elections as courts in Alabama and Florida ruled recently that Republican-led legislatures had unfairly diluted the voting power of Black residents. But those cases are just two of about a dozen that could carry big consequences as Republicans campaign to hold onto their slim majority in the U.S. House of Representatives. Another trial alleging racial violations in voting districts got underway Tuesday in Georgia, where Democrats also hope to make gains while voting rights advocates in Ohio decided to drop a legal challenge to that state’s congressional districts — providing a bit of good news for Republicans. Legal challenges to congressional districts also are ongoing in Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, New Mexico, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Utah. And new districts seem likely in New York and North Carolina, based on previous court actions. Though much remains to be settled, there’s a good chance congressional districts will be changing in numerous states. It’s likely that “a significant number of voters will be voting for a different person than they voted for in 2022,” said Doug Spencer, an election law professor at the University of Colorado who manages the All About Redistricting website. Republicans currently hold a 222-212 majority in the U.S. House, with one vacancy in a previously Democratic-held seat. Boundaries for the nation’s House districts were redrawn in all states before the 2022 election to account for population changes noted in the 2020 census. In some states, majority party lawmakers in charge of redistricting manipulated lines to give an edge to their party’s candidates — a tactic known as gerrymandering. That triggered lawsuits, which can take years to resolve. The court battle in Alabama, for example, already has lasted about two years since the legislature approved U.S. House districts that resulted in six Republicans and just one Democrat, who is Black, winning election in 2022. In June, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a lower court’s finding that the map likely violated the federal Voting Rights Act by failing to provide Black residents — who comprise 27% of the state’s population — an opportunity to elect their preferred candidates in two districts. Alabama lawmakers responded in July by passing a revised map that maintained only one majority-Black district but boosted the percentage of Black voters in a second district from about 30% to almost 40%. A federal judicial panel on Tuesday decided that wasn’t good enough. But Republican Attorney General Steve Marshall’s office said it will again ask the U.S. Supreme Court to review that decision. Ongoing lawsuits in Georgia and Louisiana are using similar arguments to push for additional districts where Black voters could have more power. Democrats stand to gain because a majority of Black residents tend to vote for Democrats instead of Republicans. A Florida redistricting case decided Saturday by a state judge also involved race, though it relied on provisions in the state constitution instead of the Voting Rights Act. That judge said the U.S. House map enacted by GOP Gov. Ron DeSantis diminished Black voters’ ability to elect their candidate of choice in northern Florida. The judge directed Florida lawmakers to draw a new congressional map — a ruling that is likely to be appealed before it’s carried out. The litigation in southern states is “more of a racial representation issue than it is a political representation issue,” said Michael McDonald, a political science professor at the University of Florida who specializes in elections and redistricting. “But we can’t escape the political consequences, because we have a very closely balanced House of Representatives at the moment.” Though Democrats stand to gain from court challenges in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and Louisiana, Republicans appear poised to pick up seats in North Carolina, which also has experienced a series of legal twists. North Carolina currently is represented in Congress by seven Democrats and seven Republicans after the state Supreme Court — under a Democratic majority — struck down the Republican legislature’s map as an illegal partisan gerrymander and instead allowed a court-drawn map to be used in the 2022 election. While that case was on appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, voters elected a Republican majority to the North Carolina Supreme Court. Those judges in April reversed the previous ruling and declared there was no constitutional prohibition on partisan gerrymandering. The state’s GOP-led legislature is expected to pass new districts that favor their candidates before the 2024 election. A similar reversal could benefit Democrats in New York, where a state appeals court in July ordered an independent redistricting commission to start work on a new set of U.S. House districts that could be used in the 2024 election. The New York Commission had failed to reach a consensus before the 2022 election, leading to maps drawn by the Democratic-led legislature that were struck down as an unconstitutional gerrymander and replaced with court-approved maps. Republicans fared better under those maps, picking up several suburban New York City seats that could be put back into play if the districts are redrawn again. Political observers also had been keeping an eye on Ohio, where the state Supreme Court previously ruled that Republican-drawn maps were unconstitutional. Despite that, those districts were allowed to be used in the 2022 election, and Republicans won 10 of the state’s 15 U.S. House seats. The U.S. Supreme Court in June ordered the state court to take another look at the case. But voting rights groups on Tuesday told the state court that they are willing to accept the current districts in order to avoid “the continued turmoil brought about by cycles of redrawn maps and ensuing litigation.” Though lawsuits have become common after each decennial redistricting, they can lead to confusion among voters if congressional districts get changed after only a few years. “It does undermine a little bit the theory of representative democracy if you don’t even know who represents you election to election,” Spencer said. “It’s another reason why these redistricting games are so problematic.” Republished with the permission of The Associated Press.

Randall Woodfin declares Election Day a city holiday in Birmingham

Mayor Randall Woodfin today declared Election day, November 3rd, is now a city holiday. Woodfin has been mayor since 2017. Woodfin, who has been active in working to ensure all citizens are registered to vote, took this commitment to a new level when he declared Election day a city holiday for Birmingham. On his Facebook post, he stated, “It’s always been my belief that a goal of every elected official should be to make voting easier, not harder. Over the past few years, we have seen different tactics used to attempt to erode and make more difficult our ability to vote in this country. To me, that’s just plain unacceptable. That’s why I’m officially making Election Day a city holiday in Birmingham. Making Election Day a day that is free from work should help those who are normally unable to take time off to go vote, particularly employees who work long shifts, have more than one job, and often must balance all of that with childcare. A US Census Bureau survey found that about 14% of respondents, about 2.7 million people, said the main reason they did not vote was because they were too busy to do so. So that’s it. We’re making Election Day a city holiday and instead of a day worrying about trying to carve out time to go vote, we’re turning Election Day into a celebration of our democracy. And if for some reason you still aren’t able to make it out to vote on Election Day, you can vote right now at your county courthouse by in-person absentee ballot. This year more than ever, we need to be breaking down the barriers that prevent our residents from having their voices heard. VOTE.” Other cities and states have worked to make Election day a holiday as well. In April, Virginia Governor Ralph Northam signed a series of laws to expand access to voting. States including Delaware, Hawaii, Kentucky, and New York have also proposed similar laws. State offices typically close, though it depends on the state whether employees are entitled to paid time off to vote. Supporters of these types of laws argue that making it a national holiday would improve voter turnout. “Voting is a fundamental right, and these new laws strengthen our democracy by making it easier to cast a ballot, not harder,” Northam stated. Around 240 million citizens are eligible to vote this year, according to Michael McDonald, who runs the U.S. Elections Project. With one week left before election day, more than 66 million people have already voted – nearly half of the total votes counted in the 2016 general election. That means the total voter turnout could be higher than 62% this year, an increase from the 2016 election.

Early vote total exceeds 2016; GOP chips at Dems’ advantage

With nine days before Election Day, more people already have cast ballots in this year’s presidential election than voted early or absentee in the 2016 race as the start of in-person early voting in big states led to a surge in turnout in recent days. The opening of early voting locations in Florida, Texas and elsewhere has piled millions of new votes on top of the mail ballots arriving at election offices as voters try to avoid crowded places on Nov. 3 during the coronavirus pandemic. The result is a total of 58.6 million ballots cast so far, more than the 58 million that The Associated Press logged as being cast through the mail or at in-person early voting sites in 2016. Democrats have continued to dominate the initial balloting, but Republicans are narrowing the gap. GOP voters have begun to show up as early in-person voting, a sign that many heeded President Donald Trump’s unfounded warnings about mail-voting fraud. On Oct. 15, Democrats registrants cast 51% of all ballots reported, compared with 25% from Republicans. On Sunday, Democrats had a slightly smaller lead, 51% to 31%. The early vote totals, reported by state and local election officials and tracked by the AP, are an imperfect indicator of which party may be leading. The data only shows party registration, not which candidate voters support. Most GOP voters are expected to vote on Election Day. Analysts said the still sizable Democratic turnout puts extra pressure on the Republican Party to push its voters out in the final week and, especially, on Nov. 3. That’s especially clear in closely contested states such as Florida, Nevada and North Carolina. “This is a glass half-full, glass half-empty situation,” said John Couvillon, a Republican pollster who tracks early voting closely. “They’re showing up more,” he added, but “Republicans need to rapidly narrow that gap.” In Florida, for example, Democrats have outvoted Republicans by a 596,000 margin by mail, while Republicans only have a 230,000 edge in person. In Nevada, where Democrats usually dominate in-person early voting but the state decided to send a mail ballot to every voter this year, the GOP has a 42,600 voter edge in-person while Democrats have an 97,500 advantage in mail ballots. “At some point, Republicans have to vote,” said Michael McDonald, a University of Florida political scientist who tracks early voting on ElectProject.org. “You can’t force everyone through a vote center on Election Day. Are you going to expect all those Republicans to stand in line for eight hours?” Campaigns typically push their voters to cast ballots early so they can focus scarce resources chasing more marginal voters as the days tick down to Election Day. That usually saves them money on mailers and digital ads — something the cash-strapped Trump campaign would likely want — and minimizes the impact of late surprises that could change the race. Trump’s campaign has been pushing its voters to cast ballots early, but with limited success, delighting Democrats. “We see the Trump campaign, the RNC (Republican National Committee) and their state parties urging Trump’s supporters to vote by mail while the president’s Twitter account says it’s a fraud,” Tom Bonier, a Democratic data analyst, said on a recent call with reporters. “The Twitter account is going to win every time.” But Bonier warned that he does not expect a one-sided election. “There are signs of Republicans being engaged,” he said. “We do expect them to come out in very high numbers on Election Day.” That split in voting behavior — Democrats voting early, Republicans on Election Day — has led some Democrats to worry about Trump declaring victory because early votes are counted last in Rust Belt battlegrounds. But they’re counted swiftly in swing states such as Arizona, Florida and North Carolina, which may balance out which party seems ahead on election night. Some of the record-setting turnout has led to long lines at early-vote locations and there have been occasional examples of voters receiving mail ballots that are incorrectly formatted. But on a whole, voting has gone relatively smoothly. With more than one-third of the 150 million ballots that experts predict will be cast in the election, there have been no armed confrontations at polling places or massive disenfranchisement that have worried election experts for months. One sign of enthusiasm is the large number of new or infrequent voters who have already voted — 25% of the total cast, according to an AP analysis of data from the political data firm L2. Those voters are younger than a typical voter and less likely to be white. So far similar shares of them are registering Democratic and Republican. They have helped contribute to enormous turnouts in states such as Georgia, where 26.3% of the people who’ve voted are new or infrequent voters, and Texas, which is expected to set turnout record and where 30.5% are new or infrequent voters. The strong share of new and infrequent voters in the early vote is part of what leads analysts to predict more than 150 million total votes will be cast and possibly the highest turnout in a U.S. presidential election since 1908. “There’s a huge chunk of voters who didn’t cast ballots in 2016,” Bonier said. “They’re the best sign of intensity at this point.” Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.