Bradley Byrne: Democrats’ Postal Service hoax

Congressman Byrne outlines the ongoing controversy with Postal Service funding.

Amid outcry, postmaster general to testify before House

Facing a public backlash over mail disruptions, the Trump administration scrambled to respond Monday as the House prepared an emergency vote to halt delivery delays and service changes that Democrats warned could imperil the November election. The Postal Service said it has stopped removing mailboxes and mail-sorting machines amid an outcry from lawmakers. President Donald Trump flatly denied he was asking for the mail to be delayed even as he leveled fresh criticism on universal ballots and mail-in voting. “Wouldn’t do that,” Trump told reporters Monday at the White House. “I have encouraged everybody: Speed up the mail, not slow the mail.” Embattled Postmaster General Louis DeJoy will testify next Monday before Congress, along with the chairman of the Postal Service board of governors. Democrats and some Republicans say actions by the new postmaster general, a Trump ally and a major Republican donor, have endangered millions of Americans who rely on the post office to obtain prescription drugs and other needs, including an expected surge in mail-in voting this fall. Speaker Nancy Pelosi is calling the House back into session over the crisis at the Postal Service, setting up a political showdown amid growing concerns that the Trump White House is trying to undermine the agency ahead of the election. Pelosi cut short lawmakers’ summer recess with a vote expected Saturday on legislation that would prohibit changes at the agency. The package will also include $25 billion to shore up the Postal Service, which faces continued financial losses. The Postal Service is among the nation’s oldest and more popular institutions, strained in recent years by declines first-class and business mail, but now hit with new challenges during the coronavirus pandemic. Trump routinely criticizes its business model, but the financial outlook is far more complex, and includes an unusual requirement to pre-fund retiree health benefits that advocates in Congress want to undo. Ahead of the election, DeJoy, a former supply-chain CEO who took over the Postal Service in June, has sparked a nationwide outcry over delays, new prices, and cutbacks just as millions of Americans will be trying to vote by mail and polling places during the COVID-19 crisis. Trump on Monday defended DeJoy, but also criticized postal operations and claimed that universal mail-in ballots would be “a disaster.” “I want to make the post office great again,” Trump said on “Fox & Friends.” Later at the White House, Trump told reporters he wants “to have a post office that runs without losing billions and billions of dollars a year.” The decision to recall the House carries a political punch. Voting in the House will highlight the issue after the weeklong Democratic National Convention nominating Joe Biden as the party’s presidential pick and pressure the Republican-held Senate to respond. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell sent senators home for a summer recess. “In a time of a pandemic, the Postal Service is Election Central,” Pelosi wrote Sunday in a letter to colleagues, who had been expected to be out of session until September. “Lives, livelihoods and the life of our American Democracy are under threat from the president.” At an event in his home-state Monday, McConnell distanced himself from Trump’s complaints about mail operations. But the Republican leader also declined to recall senators to Washington, vowing the Postal Service “is going to be just fine.” “We’re going to make sure that the ability to function going into the election is not adversely affected,” McConnell said in Horse Cave, Ky. “And I don’t share the president’s concerns.” Two Democratic lawmakers called on the FBI to investigate actions by DeJoy and the board of governors to slow the mail. “It is not unreasonable to conclude that Postmaster General DeJoy and the Board of Governors may be executing Donald Trump’s desire to affect mail-in balloting,” Reps. Ted Lieu of California and Hakeem Jeffries of New York wrote in a letter to FBI Director Christopher Wray. Senate Democratic leader Chuck Schumer and other Democrats, meanwhile, urged the postal board to use authority under a 1970 law to reverse operational changes put in place last month by DeJoy. If he declines to cooperate, “you have the authority, under the Postal Reorganization Act, to remove the postmaster general,” the senators said in a letter to board members. Outside a post office in Baltimore, Rep. Kweisi Mfume, D-Md., called on DeJoy to resign. “Don’t tell me or others that you’re just trying to make the post office make money. The U.S. post office is not a business. It is a service. And it is a service to Americans that we must always protect,” Mfume said Monday. Congress is at a standoff over postal operations. House Democrats approved $25 billion in a COVID-19 relief package but Trump and Senate Republicans have balked at additional funds for election security. McConnell held a conference call Monday with Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and GOP senators on the broader virus aid package. The Postal Service said Sunday it would stop removing its distinctive blue mailboxes through mid-November following complaints from customers and members of Congress that the collection boxes were being taken away. And White House chief of staff Mark Meadows pledged that that “no sorting machines are going offline between now and the election.” The legislation set for Saturday’s vote, the “Delivering for America Act,” would prohibit the Postal Service from implementing any changes to operations or level of service it had in place on Jan. 1. The package would include the $25 billion in earlier funds that are stalled in the Senate. DeJoy, the first postmaster general in nearly two decades who was not a career postal employee, has pledged to modernize the money-losing agency to make it more efficient. He eliminated most overtime for postal workers, imposed restrictions on transportation, and reduced the quantity and use of mail-processing equipment. Trump said last week that he was blocking emergency aid to the Postal Service, as well as a Democratic proposal to provide $3.6 billion in additional election money to the states to help process an expected surge

Nancy Pelosi to call House back into session to vote on USPS bill

Pelosi is cutting short lawmakers’ summer recess with a vote expected the Saturday after the Democratic National Convention on legislation that would prohibit changes at the agency as tensions mount.

For Americans waiting on virus aid, no new relief in sight

Negotiations over a new virus relief package have all but ended.

In virus talks, Nancy Pelosi holds firm; Steven Mnuchin wants a deal

There are limits, and legal pitfalls, in trying to make an end run around the legislative branch.

Bradley Byrne: A way forward on coronavirus relief

Bradley Byrne criticizes Democratic leadership’s handling of the next round of coronavirus economic relief.

John Lewis mourned as ‘founding father’ of better America

Former President Barack Obama called Lewis “a man of pure joy and unbreakable perseverance” during a fiery eulogy that was both deeply personal and political.

Donald Trump offers, Democrats reject fix for $600 jobless benefit

Democratic leaders panned the idea in late-night talks at the Capitol.

Donald Trump floats idea of election delay, a virtual impossibility

The date of the presidential election is enshrined in federal law and would require an act of Congress to change.

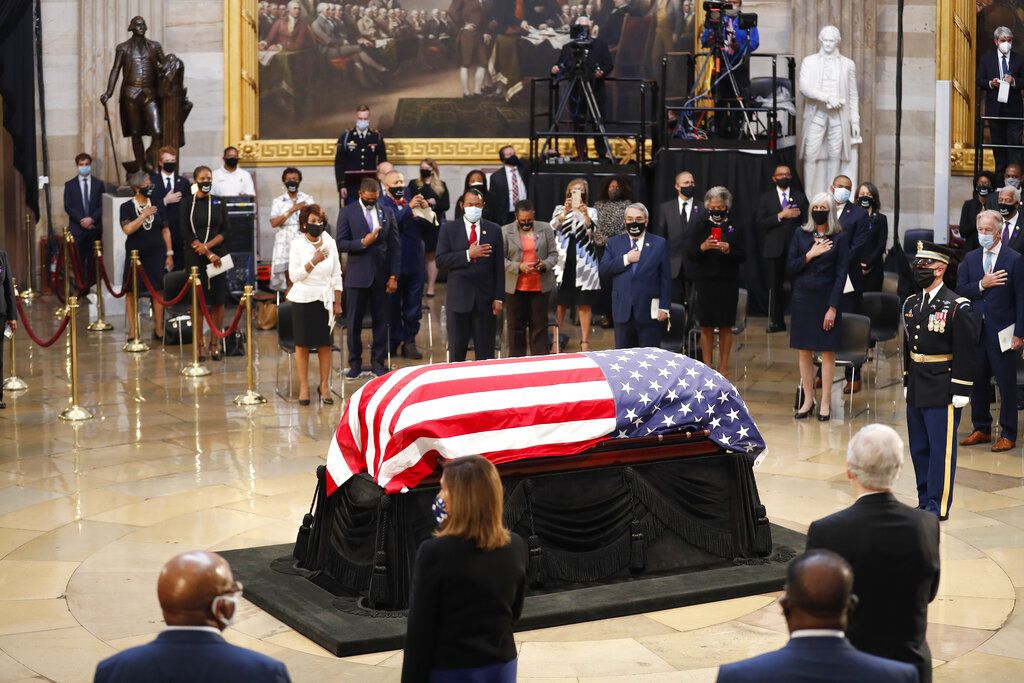

Civil rights icon Rep. John Lewis lies in state at Capitol

In a solemn display of bipartisan unity, congressional leaders praised Democratic Rep. John Lewis as a moral force for the nation on Monday in a Capitol Rotunda memorial service rich with symbolism and punctuated by the booming, recorded voice of the late civil rights icon. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi called Lewis the “conscience of the Congress” who was “revered and beloved on both sides of the aisle, on both sides of the Capitol.” Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell praised the longtime Georgia congressman as a model of courage and a “peacemaker.” “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” McConnell, a Republican, said, quoting the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. “But that is never automatic. History only bent toward what’s right because people like John paid the price.” Lewis died July 17 at the age of 80. Born to sharecroppers during Jim Crow segregation, he was beaten by Alabama state troopers during the civil rights movement, spoke ahead of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech at the 1963 March on Washington and was awarded the Medal of Freedom by the nation’s first Black president in 2011. Dozens of lawmakers looked on Monday as Lewis’ flag-draped casket sat atop the catafalque built for President Abraham Lincoln. Several wiped away tears as the late congressman’s voice echoed off the marble and gilded walls. Lewis was the first Black lawmaker to lie in state in the Rotunda. “You must find a way to get in the way. You must find a way to get in trouble, good trouble, necessary trouble,” Lewis intoned in a recorded commencement address he’d delivered in his hometown of Atlanta. “Use what you have … to help make our country and make our world a better place, where no one will be left out or left behind. … It is your time.” Members of the Congressional Black Caucus wore masks with the message “Good Trouble,” a nod to Lewis’ signature advice and the COVID-19 pandemic that has made for unusual funeral arrangements. The ceremony was the latest in a series of public remembrances. Pelosi, who counted Lewis as a close friend, met his casket earlier Monday at Joint Base Andrews in Maryland, and Lewis’ motorcade stopped at Black Lives Matter Plaza near the White House as it wound through Washington before arriving at the Capitol. The Democratic speaker noted that Lewis, frail with cancer, had come to the newly painted plaza weeks ago to stand “in solidarity” amid nationwide protests against systemic racism and police brutality. She called the image of Lewis “an iconic picture of justice” and juxtaposed it with another image that seared Lewis into the national memory. In that frame, “an iconic picture of injustice,” Pelosi said, Lewis is collapsed and bleeding near the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, on March 7, 1965, when state troopers beat him and other Black Americans as they demanded voting rights. Following the Rotunda service, Lewis’ body was moved to the steps on the Capitol’s east side in public view, an unusual sequence required because the pandemic has closed the Capitol to visitors. Late into the night, a long line of visitors formed outside the Capitol as members of the public quietly, and with appropriate socially distant spacing, came to pay their respects to Lewis. Presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden paid his respects late Monday afternoon. The pair became friends over their two decades on Capitol Hill together and Biden’s two terms as vice president to President Barack Obama, who awarded Lewis the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2011. Notably absent from the ceremonies was President Donald Trump. Lewis once called Trump an illegitimate president and chided him for stoking racial discord. Trump countered by blasting Lewis’ Atlanta district as “crime-infested.” Trump said Monday that he would not go to the Capitol, but Vice President Mike Pence and his wife paid their respects. Just ahead of the ceremonies, the House passed a bill to establish a new federal commission to study conditions that affect Black men and boys. Born near Troy, Alabama, Lewis was among the original Freedom Riders, young activists who boarded commercial passenger buses and traveled through the segregated Jim Crow South in the early 1960s. They were assaulted and battered at many stops, by citizens and authorities alike. Lewis was the youngest and last-living of those who spoke on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial at the March on Washington. The Bloody Sunday events in Selma two years later forged much of Lewis’ public identity. He was at the head of hundreds of civil rights protesters who attempted to march from the Black Belt city to the Alabama Capitol in Montgomery. The marchers completed the journey weeks later under the protection of federal authorities, but then-Alabama Gov. George C. Wallace, an outspoken segregationist at the time, refused to meet the marchers when they arrived at the Capitol. President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 on Aug. 6 of that year. Lewis spoke of those critical months for the rest of his life as he championed voting rights as the foundation of democracy, and he returned to Selma many times for commemorations at the site where authorities had brutalized him and others. “The vote is precious. It is almost sacred,” he said again and again. “It is the most powerful nonviolent tool we have in a democracy.” The Supreme Court scaled back the seminal voting law in 2012; an overhauled version remains bottle-necked on Capitol Hill, with Democrats pushing a draft that McConnell and most of his fellow Republicans oppose. The new version would carry Lewis’ name. Lewis crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge for the last time Sunday on a horse-drawn carriage before an automobile hearse transported him to the Alabama Capitol, where he lay in repose. He was escorted by Alabama state troopers, this time with Black officers in their ranks, and his casket stood down the hall from the office where Wallace had peered out of

John Lewis funeral to be held at Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist

The funeral for the late civil rights icon and Congressman John Lewis will be held Thursday at Atlanta’s historic Ebenezer Baptist Church, which the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. once led. Lewis’ family announced that the funeral will be private, but the public is invited to pay tribute over the coming days during a series of celebrations of Lewis’ life beginning Saturday in his hometown of Troy, Alabama. On Sunday morning, a processional will be held in which Lewis’ body will once more cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where he and other voting rights demonstrators were beaten 55 years ago on “Bloody Sunday.” Lewis’s body will also lie in state at the Alabama State Capitol in Montgomery, the Georgia State Capitol in Atlanta, and the U.S. Capitol in Washington. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell announced Thursday that the public will be allowed to pay their respects in Washington to the longtime Georgia congressman Monday night and all day Tuesday. Due to coronavirus precautions, Lewis will lie in state for public viewing at the top of the east front steps of the Capitol rather than in the Rotunda, and the public will file past on the East Plaza. Face masks will be required and social distancing will be enforced. Lewis’ family has asked members of the public not to travel from across the country to pay their respects. Instead, they suggested people pay virtual tribute online using the hashtags #BelovedCommunity or #HumanDignity. Lewis, 80, died last Friday, several months after he was diagnosed with advanced pancreatic cancer. He served 17 terms in the U.S. House. Following the funeral at the Ebenezer Baptist Church Horizon Sanctuary, he will be interred at South View Cemetery in Atlanta. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

White House drops payroll tax cut after GOP allies object

President Donald Trump on Thursday reluctantly dropped his bid to cut Social Security payroll taxes as Republicans stumbled anew in efforts to unite around a $1 trillion COVID-19 rescue package to begin negotiations with Democrats who are seeking far more. Frustrating new delays came as the administration scrambled to avert the cutoff next week of a $600-per-week bonus unemployment benefit that has helped prop up the economy while staving off financial disaster for millions of people thrown out of work since the coronavirus pandemic began. Trump yielded to opposition to the payroll tax cut among his top Senate allies, claiming in a Twitter post that Democratic opposition was the reason. In fact, top Senate Republicans disliked the expensive idea in addition to opposition from Democrats for the cut in taxes that finance Social Security and Medicare. “The Democrats have stated strongly that they won’t approve a Payroll Tax Cut (too bad!). It would be great for workers. The Republicans, therefore, didn’t want to ask for it,” Trump contended. “The president is very focused on getting money quickly to workers right now, and the payroll tax takes time,” Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said at the Capitol. Only Sunday, Trump said in a Fox News interview that “I would consider not signing it if we don’t have a payroll tax cut.” The long-delayed legislation comes amid alarming new cases in the virus crisis. It was originally to be released Thursday morning by Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. But the Kentucky Republican instead hosted an unscheduled meeting with Mnuchin and White House acting chief of staff Mark Meadows and delayed the planned release of the proposal until next week. The rocky developments coincide with a higher-profile role by Meadows, a former tea party lawmaker from North Carolina with a thin legislative resume. The delays increase the chances that efforts to pass the COVID rescue, the fifth coronavirus response bill this year, could drag well into August as both parties are formally nominating their presidential candidates. Mnuchin claimed there was “fundamental agreement” on the GOP side, but irritation was growing among Republicans with the Trump negotiating team, which floated the idea of breaking off a smaller bill that would be limited to maintaining some jobless benefits and speeding aid to schools. Democrats immediately panned that idea, saying it would strand other important elements such as aid to state and local governments. “We cannot piecemeal this,” declared House Speaker Nancy Pelosi of California. As a practical matter, Democrats say, the only way to prevent a cutoff of the pandemic jobless benefit next month is to simply extend it in full, at least in the short term. Balky and ancient state unemployment systems can’t be adjusted in time to immediately implement a new compromise. “Due to ancient technology, states need between one and four weeks to adjust the $600 boost. At this late hour, the only option to guarantee benefits do not lapse is the Democratic plan to extend the $600 weekly benefit,” said top Finance Committee Democrat Ron Wyden of Oregon. “Republicans rejected that plan outright. They were never serious about preventing a lapse in benefits.” McConnell scrapped a choreographed rollout that would have featured Republicans with tough reelection races claiming credit for provisions like a $15 billion appropriation for child care assistance for parents trying to go back to work while many schools will remain closed this fall. McConnell now says the rollout won’t come out until next week. “Our Republican colleagues have been so divided, so disorganized and so unprepared that they have to struggle to draft even a partisan proposal within their own conference,” said Democratic leader Chuck Schumer. The must-have centerpiece for McConnell is a liability shield to protect businesses, schools and others from coronavirus-related lawsuits. The still-unreleased GOP measure does forge an immediate agreement with Democrats on another round of $1,200 checks to most adults. The $600 weekly unemployment benefit boost that is expiring Friday would be cut back, and Mnuchin said it would ultimately be redesigned to provide a typical worker 70% of his or her income. Republicans say extending it in full would be a disincentive to work. “You can’t continue to pay people more to not work than to work,” said Sen. John Barrasso of Wyoming. The Republican package will also include tax breaks for businesses to hire and retain workers and to help shops and workplaces retool with new safety protocols. A document circulating among lobbyists claims the package would increase the deduction for business meals to 100%, offering help to the restaurant industry. Mnuchin said there is bipartisan agreement on changes to a popular subsidy program for businesses called the Paycheck Protection Program that would permit businesses especially hard hit by the pandemic — companies with fewer than 300 workers and revenue losses of 50% — to receive a second PPP payment. A breakthrough on $25 billion in virus-testing money was key after days of wrangling between Republicans on the powerful Appropriations Committee and the White House. There will also be $26 billion for vaccines and $15 billion for research programs at the National Institutes of Health. At the White House, Trump touted the GOP plan’s massive $105 billion to help schools and universities reopen. It contains $70 billion to help K-12 schools reopen, $30 billion for colleges, and $5 billion for governors to allocate. Trump said he wants the school money linked to reopenings. In McConnell’s package, the money for K-12 would be split between those that have in-person learning and those that don’t. If local public schools don’t reopen, the money should go to parents to send their children to other schools or teach them at home, Trump said. “If the school is closed, the money should follow the student,” he said. Democrats back a much more sweeping package, including almost $1 trillion for state and local governments. They also want a fresh round of mortgage and rental assistance and new federal health and safety requirements for workers — ideas strongly opposed by Republicans. Congress