Texas AG Ken Paxton sues Pfizer citing misrepresentation of COVID-19 vaccine efficacy

By Bethany Blankley | The Center Square contributor Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton sued Pfizer on Thursday, alleging the pharmaceutical giant unlawfully misrepresented the effectiveness of its COVID-19 vaccine and attempted to censor public discussion about it. The lawsuit comes six months after his office launched an investigation into three pharmaceutical giants in May. It was filed in the District Court of Lubbock County, Texas, and solely names Pfizer., Inc., as the defendant. Paxton alleges that Pfizer engaged in false, deceptive, and misleading acts and practices by making unsupported claims about its COVID-19 vaccine in violation of the Texas Deceptive Trade Practices Act. Because of Pfizer’s claims, “placing their trust in Pfizer, hundreds of millions of Americans lined up to receive the vaccine,” Paxton’s 54-page brief states. “Contrary to Pfizer’s public statements, however, the pandemic did not end; it got worse. “More Americans died in 2021, with Pfizer’s vaccine available, than in 2020, the first year of the pandemic. This, in spite of the fact that the vast majority of Americans received a COVID-19 vaccine, with most taking Pfizer’s.” Paxton’s lawsuit adds: “By the end of 2021, official government reports showed that in at least some places, a greater percentage of the vaccinated were dying from COVID-19 than the unvaccinated. Pfizer’s vaccine plainly was not ‘95% effective.’” By October 2022, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that roughly 226.6 million people were fully vaccinated after receiving one Johnson & Johnson dose or two doses of Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines, the New York Times reported. Another more than 111 million people received additional booster shots at the time. The complaint notes that Pfizer’s efficacy claim was based on a “relative risk reduction” metric used during its initial, two-month clinical trial. Such metrics, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, are misleading and “‘unduly influence[s]’ consumer choice.” It also states that Pfizer’s clinical trial “failed to measure whether the vaccine protects against transmission;” despite this, Pfizer “embarked on a campaign to intimidate the public into getting the vaccine as a necessary measure to protect their loved ones.” When efficacy failed, “Pfizer then pivoted to silencing truth-tellers,” Paxton argues. The brief states, “How did Pfizer respond when it became apparent that its vaccine was failing and the viability of its cash cow was threatened? By intimidating those spreading the truth, and by conspiring to censor its critics. Pfizer labeled as ‘criminals’ those who spread facts about the vaccine. It accused them of spreading ‘misinformation.’ And it coerced social media platforms to silence prominent truth-tellers.” The lawsuit follows an investigation Paxton launched into Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson in May to determine if the companies engaged in gain-of-function research and misled the public about their practices. The investigation sought to determine if the companies misrepresented the efficacy of their COVID-19 vaccines and violated the Texas Deceptive Trade Practices Act. Investigators also looked into potential manipulation of vaccine trial data and the “relative risk reduction” method that was used instead of “absolute risk reduction” method. Paxton’s lawsuit stems from information it received after sending Civil Investigative Demands to the pharmaceutical giants. The COVID-lockdown era “was a deeply challenging time for Americans,” Paxton said when launching the investigation. “If any company illegally took advantage of consumers during this period or compromised people’s safety to increase their profits, they will be held responsible. If public health policy was developed on the basis of flawed or misleading research, the public must know. The catastrophic effects of the pandemic and subsequent interventions forced on our country and citizens deserve intense scrutiny, and we are pursuing any hint of wrongdoing to the fullest.” The federal government under former President Donald Trump entered into a $1.9 billion agreement with Pfizer, which was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on Dec. 11, 2020. Trump pushed the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine through what he called “Operation Warp Speed,” making it available through Emergency Use Authorization as an experimental drug. Operation Warp Speed spent $12.4 billion on the vaccines, TIME reported. As Pfizer declared its vaccine was “95% effective,” on Dec. 17, 2020, Trump tweeted, “The Vaccine and the Vaccine rollout are getting the best of reviews. Moving along really well. Get those ‘shots’ everyone!” After he lost his reelection, at an RNC event at Mar-a-Lago in April 2021, Trump said everyone should refer to the COVID-19 vaccines as the “Trumpcine.” In a January 2022 interview, he said the “vaccines saved tens of millions throughout the world.” His former White House domestic policy advisor Joe Grogan also said Trump “handed [President Joe] Biden three vaccines,” TIME reported. “Biden is just really making our COVID response look a lot better than the media gave us credit for.” Trump continues to take credit for the vaccines, arguing they are effective and saved lives. Republished with the permission of The Center Square.

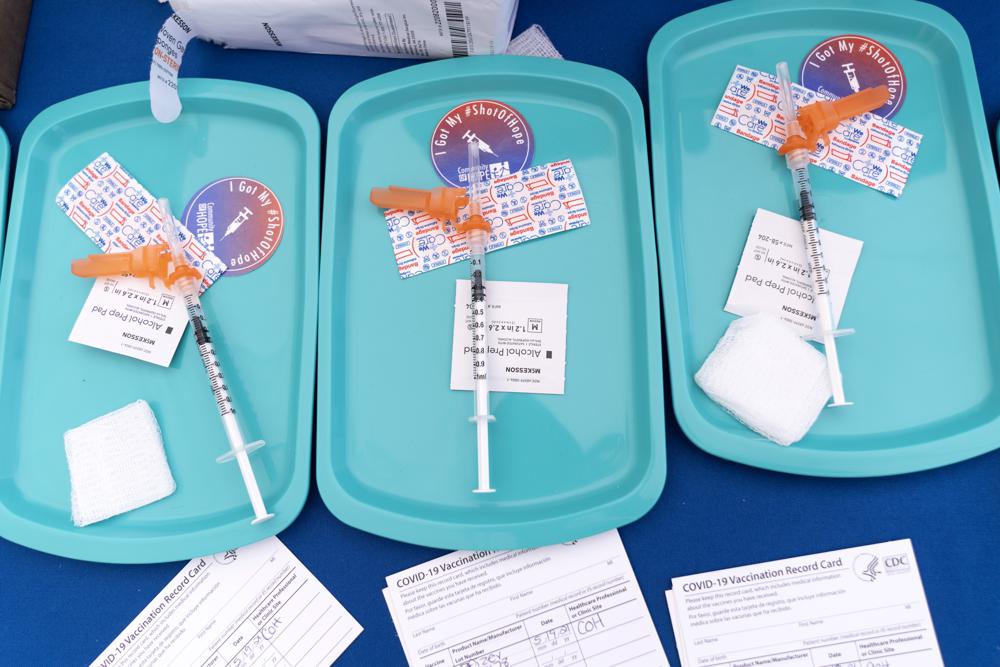

White House: 1st COVID-19 shots for kids under 5 possible by June 21

The Biden administration said Thursday that children under 5 may be able to get their first COVID-19 vaccination doses as soon as June 21, if federal regulators authorize shots for the age group, as expected. White House COVID-19 coordinator Aashish Jha outlined the administration’s planning for the last remaining ineligible age group to get shots. He said the Food and Drug Administration’s outside panel of advisers will meet on June 14-15 to evaluate the Pfizer and Moderna shots for younger kids. Shipments to doctors’ offices and pediatric care facilities would begin soon after FDA authorization, with the first shots possible the following week. Jha said states can begin placing orders for pediatric vaccines on Friday, and said the administration has an initial supply of 10 million doses available. He said it may take a few days for the vaccines to arrive across the country and vaccine appointments to be widespread. “Our expectation is that within weeks every parent who wants their child to get vaccinated will be able to get an appointment,” Jha said. The Biden administration is pressing states to prioritize large-volume sites like children’s hospitals, and to make appointments available outside regular work hours to make it easier for parents to get their kids vaccinated. Jha acknowledged the “frustration” of parents of young children who have been waiting more than a year for shots for their kids. “At the end of the day we all want to move fast, but we’ve got to get it right,” he said. Republished with the permission of The Associated Press.

U.S. opens second COVID boosters to 50 and up, others at risk

Americans 50 and older can get a second COVID-19 booster if it’s been at least four months since their last vaccination, a chance at extra protection for the most vulnerable in case the coronavirus rebounds. The Food and Drug Administration on Tuesday authorized an extra dose of the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine for that age group and for certain younger people with severely weakened immune systems. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention later recommended the extra shot as an option but stopped short of urging that those eligible rush out and get it right away. That decision expands the additional booster to millions more Americans. Dr. Rochelle Walensky, CDC’s director, said it was especially important for older Americans — those 65 and older — and the 50-somethings with chronic illnesses such as heart disease or diabetes to consider another shot. “They are the most likely to benefit from receiving an additional booster dose at this time,” Walensky said. There’s evidence protection can wane, particularly in higher-risk groups, and for them, another booster “will help save lives,” FDA vaccine chief Dr. Peter Marks said. For all the attention on who should get a fourth dose of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, only about half of Americans eligible for a third shot have gotten one — and the government urged them to get up to date. Two shots plus a booster still offer strong protection against severe illness and death, even during the winter surge of the super-contagious omicron variant. The move toward additional boosters comes at a time of great uncertainty, with limited evidence to tell how much benefit an extra dose right now could offer. COVID-19 cases have dropped to low levels in the U.S., but all vaccines are less powerful against newer mutants than earlier versions of the virus — and health officials are warily watching an omicron sibling that’s causing worrisome jumps in infections in other countries. Pfizer had asked the FDA to clear a fourth shot for people 65 and older, while Moderna requested another dose for all adults “to provide flexibility” for the government to decide who really needs one. FDA’s Marks said regulators set the age at 50 because that’s when chronic conditions that increase the risks from COVID-19 become more common. Until now, the FDA had allowed a fourth vaccine dose only for the immune-compromised as young as 12. Vaccines have a harder time revving up severely weak immune systems, and Marks said their protection also tends to wane sooner. Tuesday’s decision allows them another booster, too — a fifth dose. Only the Pfizer vaccine can be used in those as young as 12; Moderna’s is for adults. What about people who got Johnson & Johnson’s single-dose shot? They already were eligible for one booster of any kind. Of the 1.3 million who got a second J&J shot, the CDC said now they may choose a third dose — either Moderna or Pfizer. For the more than 4 million who got Moderna or Pfizer as their second shot, the CDC says an additional booster is only necessary if they meet the newest criteria — a severely weakened immune system or are 50 or older. That’s because a CDC study that tracked which boosters J&J recipients initially chose concluded a Moderna or Pfizer second shot was superior to a second J&J dose. If the new recommendations sound confusing, outside experts say it makes sense to consider extra protection for the most vulnerable. “There might be a reason to top off the tanks a little bit” for older people and those with other health conditions said University of Pennsylvania immunologist E. John Wherry, who wasn’t involved in the government’s decision. But while he encourages older friends and relatives to follow the advice, the 50-year-old Wherry — who is healthy, vaccinated, and boosted — doesn’t plan on getting a fourth shot right away. With protection against severe illness still strong, “I’m going to wait until it seems like there’s a need.” While protection against milder infections naturally wanes over time, the immune system builds multiple layers of defense, and the type that prevents severe illness and death is holding up. During the U.S. omicron wave, two doses were nearly 80% effective against needing a ventilator or death — and a booster pushed that protection to 94%, the CDC recently reported. Vaccine effectiveness was lowest — 74% — in immune-compromised people, the vast majority of whom hadn’t gotten a third dose. To evaluate an extra booster, U.S. officials looked to Israel, which opened a fourth dose to people 60 and older during the omicron surge. The FDA said no new safety concerns emerged in a review of 700,000 fourth doses administered. Preliminary data posted online last week suggested some benefit: Israeli researchers counted 92 deaths among more than 328,000 people who got the extra shot, compared to 232 deaths among 234,000 people who skipped the fourth dose. What’s far from clear is how long any extra benefit from another booster would last, and thus when to get it. “The ‘when’ is a really difficult part. Ideally, we would time booster doses right before surges but we don’t always know when that’s going to be,” said Dr. William Moss, a vaccine expert at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Plus, a longer interval between shots helps the immune system mount a stronger, more cross-reactive defense. “If you get a booster too close together, it’s not doing any harm — you’re just not going to get much benefit from it,” said Wherry. The newest booster expansion may not be the last: Next week, the government will hold a public meeting to debate if everyone eventually needs a fourth dose, possibly in the fall, of the original vaccine or an updated shot. Even if higher-risk Americans get boosted now, Marks said they may need yet another dose in the fall if regulators decide to tweak the vaccine. For that effort, studies in people — of omicron-targeted shots alone or in

Moderna says its low-dose COVID shots work for kids under 6

Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine works in babies, toddlers, and preschoolers, the company announced Wednesday — a development that could pave the way for the littlest kids to be vaccinated by summer if regulators agree. Moderna said that in the coming weeks it would ask regulators in the U.S. and Europe to authorize two small-dose shots for youngsters under 6. The company also is seeking to have larger doses cleared for older children and teens in the U.S. The announcement is positive news for parents who have anxiously awaited protection for younger tots and have been continuously disappointed by setbacks and confusion over which shots might work and when. The nation’s 18 million children under 5 are the only age group not yet eligible for vaccination. Moderna says early study results show tots develop high levels of virus-fighting antibodies from shots containing a quarter of the dose given to adults. Once Moderna submits its full data, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration will have to determine if that important marker means the youngsters are as protected against severe illness as adults. “The vaccine provides the same level of protection against COVID in young kids as it does in adults. We think that’s good news,” Dr. Stephen Hoge, Moderna’s president, told The Associated Press. But that key antibody finding isn’t the whole story. COVID-19 vaccines aren’t as effective against the super-contagious omicron mutant — in people of any age — and Moderna’s study found the same trend. There were no severe illnesses during the trial but the vaccine was only about 44% effective at preventing milder infections in babies up to age 2, and nearly 38% effective in the preschoolers. “Not a home run” but the shots still could be helpful for the youngest children, said Dr. Jesse Goodman of Georgetown University, a former FDA vaccine chief. Goodman said the high antibody levels seen in the study “should translate into higher efficacy against severe infections.” Some parents say even a little protection would be better than leaving their youngest children unvaccinated. “I don’t care if it’s even 15 or 20%,” said Lauren Felitti of Gaithersburg, Maryland. Her 4-year-old son Aiden, who’s at extra risk because of a heart condition, was hospitalized for eight days with COVID-19 and she’s anxious to vaccinate him to lessen the chance of a reinfection. “It was very scary,” Felitti said. “If there’s a chance that I’m able to keep him protected, even if it’s a small chance, then I’m all for it.” Competitor Pfizer currently offers kid-size doses for school-age children and full-strength shots for those 12 and older. And the company is testing even smaller doses for children under 5 but had to add a third shot to its study when two didn’t prove strong enough. Those results are expected by early April. If the FDA eventually authorizes vaccinations for little kids from either company, there still would be another hurdle. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends who should get them — and Goodman said there may be debate about shots for higher-risk children or everyone under 5. Vaccinating the littlest “has been somewhat of a moving target over the last couple of months,” Dr. Bill Muller of Northwestern University, who is helping study Moderna’s pediatric doses, said in an interview before the company released its findings. “There’s still, I think, a lingering urgency to try to get that done as soon as possible.” While COVID-19 generally isn’t as dangerous to youngsters as to adults, some do become severely ill. The CDC says about 400 children younger than 5 have died from COVID-19 since the pandemic’s start. The omicron variant hit children especially hard, with those under 5 hospitalized at higher rates than at the peak of the previous delta surge. The younger the child, the smaller the dose being tested. Moderna enrolled about 6,900 kids under 6 — including babies as young as 6 months — in a study of the 25-microgram doses. While the study wasn’t large enough to detect very rare side effects, Moderna said the small doses were safe and that mild fevers, like those associated with other common pediatric vaccines, were the main reaction. Hudson Diener, 3, only briefly cried when getting test doses at Stony Brook Medicine in Commack, New York. His parents welcomed the study results and hope to learn that Hudson received the vaccine and not dummy shots. “We are really hoping to get the answer we’re looking for soon so we can take a deep breath,” said Hudson’s mom, Ilana Diener. Wednesday’s news should “hopefully be a step closer for his age group to be eligible for the vaccine very soon.” Boosters have proved crucial for adults to fight omicron and Moderna currently is testing those doses for children as well — either a third shot of the original vaccine or an extra dose that combines protection against the original virus and the omicron variant. Parents may find it confusing that Moderna is seeking to vaccinate the youngest children before it’s cleared to vaccinate teens. While other countries already have allowed Moderna’s shots to be used in children as young as 6, the U.S. has limited its vaccine to adults. The FDA hasn’t ruled on Moderna’s earlier request to expand its shots to 12- to 17-year-olds because of concern about a very rare side effect. Heart inflammation sometimes occurs in teens and young adults, mostly males, after receiving either the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines. Moderna is getting extra scrutiny because its shots are a far higher dose than Pfizer’s. The company said Wednesday that, armed with additional evidence, it is updating its FDA application for teen shots and requesting a green light for 6- to 11-year-olds, too. Hoge said he’s optimistic the company will be able to offer its vaccine “across all age groups in the United States by the summer.” Moderna says its original adult dose — two 100-microgram shots — is safe and effective in 12- to 17-year-olds. For elementary school-age kids, it’s using half the adult

Pfizer vaccine booster dose authorized for children 12-15 years old

The Alabama Department of Public Health (ADPH) announced new Covid-19 vaccine recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The CDC has authorized the use of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine as a single booster dose in individuals 12 through 15 years of age. Previously, the booster dose of the vaccine was authorized for adolescents 16 years of age and older. The CDC also approved a third primary series dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. The third dose can be administered at least 28 days following the two-dose regimen in individuals 5 through 11 years of age who are determined to be moderately to severely immunocompromised. The updates came after an ongoing review of the available safety and efficacy data by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Any known or potential benefits of additional doses were determined to outweigh any potential vaccine risks. The CDC also lowered the authorized dosing interval of a booster dose to at least five months after completing a Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna primary series. The booster dose after the Johnson and Johnson vaccine remains at two months. The Moderna and Johnson & Johnson/Janssen vaccines are only authorized for adults 18 years of age and older. During a press conference last week, ADHP health officer Dr. Scott Harris expressed concern for Alabamans and the sudden rise in omicron variant cases. The Covid-19 positivity rate in Alabama is almost 39%. That means nearly four in 10 tests came back positive. “It will infect everyone in the state at some point, or most of them,” Harris stated. “So, we really need people to do the single most important thing they can do to protect themselves, which is to be fully vaccinated and boosted when it’s appropriate to do that.” Alabama currently has one of the nation’s lowest vaccination rates. According to the CDC, less than 48% of the state’s population is fully vaccinated. Studies show that protection decreases over time after getting vaccinated against COVID-19 and may also be decreased due to changes in circulating variants.

CDC panel recommends Pfizer, Moderna COVID shots over J&J’s

Most Americans should be given the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines instead of the Johnson & Johnson shot that can cause rare but serious blood clots, U.S. health advisers recommended Thursday. The strange clotting problem has caused nine confirmed deaths after J&J vaccinations — while the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines don’t come with that risk and also appear more effective, advisers to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said. It’s an unusual move, and the CDC’s director, Dr. Rochelle Walensky, must decide whether to accept the panel’s advice. Until now, the U.S. has treated all three COVID-19 vaccines available to Americans as an equal choice since large studies found they all offered strong protection and early supplies were limited. J&J’s vaccine initially was welcomed as a single-dose option that could be especially important for hard-to-reach groups like homeless people who might not get the needed second dose of the Pfizer or Moderna options. But the CDC’s advisers said Thursday that it was time to recognize a lot has changed since vaccines began rolling out a year ago. More than 200 million Americans are considered fully vaccinated, including about 16 million who got the J&J shot. New data from unprecedented safety tracking of all those vaccinations persuaded the panel that while the blood clots linked to J&J’s vaccine remain very rare, they’re still occurring and not just in younger women as originally thought. In a unanimous vote, the advisers decided the safer Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are preferred. But they said the shot made by J&J’s Janssen division still should be available if someone really wants it — or has a severe allergy to the other options. “I would not recommend the Janssen vaccine to my family members,” but some patients may — and should be able to — choose that shot, said CDC adviser Dr. Beth Bell of the University of Washington. The clotting problems first came up last spring, with the J&J shot in the U.S. and with a similar vaccine made by AstraZeneca that is used in other countries. Eventually, U.S. regulators decided the benefits of J&J’s one-and-done vaccine outweighed what was considered a very rare risk — as long as recipients were warned. European regulators likewise continued to recommend AstraZeneca’s two-dose vaccine although, because early reports were mostly in younger women, some countries issued age restrictions. COVID-19 causes deadly blood clots, too. But the vaccine-linked kind is different, believed to form because of a rogue immune reaction to the J&J and AstraZeneca vaccines because of how they’re made. It forms in unusual places, such as veins that drain blood from the brain, and in patients who also develop abnormally low levels of the platelets that form clots. Symptoms of the unusual clots, dubbed “thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome,” include severe headaches a week or two after the J&J vaccination — not right away — as well as abdominal pain and nausea. While it’s still very rare, the Food and Drug Administration told health care providers this week that more cases have occurred after J&J vaccinations since the spring. They occur most in women ages 30 to 49 — about once for every 100,000 doses administered, the FDA said. Overall, the government has confirmed 54 clot cases— 37 in women and 17 in men, and nine deaths that included two men, the CDC’s Dr. Isaac See said Thursday. He said two additional deaths are suspected. The CDC decides how vaccines should be used in the U.S., and its advisers called the continuing deaths troubling. In comparing the pros and cons of all the vaccines, the panelists agreed that side effects from the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines weren’t as serious — and that supplies now are plentiful. Nor is J&J still considered a one-and-done vaccine, several advisers noted. The single-dose option didn’t prove quite as protective as two doses of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines. Plus, with extra-contagious virus mutants now spreading, booster doses now are recommended. Several countries, including Canada, already have policies that give preference to the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines. But J&J told the committee its vaccine still offers strong protection and is a critical option, especially in parts of the world without plentiful vaccine supplies or for people who don’t want a two-dose shot. While blood clots are rare, “unfortunately cases of COVID-19 are not,” J&J’s Dr. Penny Heaton said. The U.S. is fortunate in its vaccine availability, and Thursday’s action shouldn’t discourage use of J&J’s vaccine in places around the world where it’s needed, said CDC adviser Dr. Matthew Daley of Kaiser Permanente Colorado. The FDA also warned this week that another dose of the J&J vaccine shouldn’t be given to anyone who developed a clot following either a J&J or AstraZeneca shot. The committee also heard some of the first data on reported side effects of Pfizer vaccinations in younger children. Early last month, the CDC recommended a two-dose series for that age group, and more than 7 million doses have been given so far. But few problems have been reported. Of the 80 reported cases of serious side effects, about 10 involved a form of inflammation that has been seen in male teens and young adults. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Pfizer says COVID-19 pill cut hospital, death risk by 90%

Pfizer Inc. said Friday that its experimental antiviral pill for COVID-19 cut rates of hospitalization and death by nearly 90% in high-risk adults, as the drugmaker joins the race to bring the first easy-to-use medication against the coronavirus to the U.S. market. Currently, all COVID-19 treatments used in the U.S. require an IV or injection. Competitor Merck’s COVID-19 pill is already under review at the Food and Drug Administration after showing strong initial results, and on Thursday, the United Kingdom became the first country to OK it. Pfizer said it will ask the FDA and international regulators to authorize its pill as soon as possible after independent experts recommended halting the company’s study based on the strength of its results. Once Pfizer applies, the FDA could make a decision within weeks or months. If authorized, the company would sell the drug under the brand name Paxlovid. Researchers worldwide have been racing to find a pill against COVID-19 that can be taken at home to ease symptoms, speed recovery, and reduce the crushing burden on hospitals and doctors. Pfizer released preliminary results Friday of its study of 775 adults. Patients who received the company’s drug along with another antiviral shortly after showing COVID-19 symptoms had an 89% reduction in their combined rate of hospitalization or death after a month, compared to patients taking a dummy pill. Fewer than 1% of patients taking the drug needed to be hospitalized, and no one died. In the comparison group, 7% were hospitalized, and there were seven deaths. “We were hoping that we had something extraordinary, but it’s rare that you see great drugs come through with almost 90% efficacy and 100% protection for death,” said Dr. Mikael Dolsten, Pfizer’s chief scientific officer, in an interview. Study participants were unvaccinated, with mild-to-moderate COVID-19, and were considered high risk for hospitalization due to health problems like obesity, diabetes, or heart disease. Treatment began within three to five days of initial symptoms and lasted for five days. Patients who received the drug earlier showed slightly better results, underscoring the need for speedy testing and treatment. Pfizer reported few details on side effects but said rates of problems were similar between the groups at about 20%. An independent group of medical experts monitoring the trial recommended stopping it early, standard procedure when interim results show such a clear benefit. The data have not yet been published for outside review, the normal process for vetting new medical research. Top U.S. health officials continue to stress that vaccination will remain the best way to protect against infection. But with tens of millions of adults still unvaccinated — and many more globally — effective, easy-to-use treatments will be critical to curbing future waves of infections. The FDA has set a public meeting later this month to review Merck’s pill, known as molnupiravir. The company reported in September that its drug cut rates of hospitalization and death by 50%. Experts warn against comparing preliminary results because of differences in studies. Although Merck’s pill is further along in the U.S. regulatory process, Pfizer’s drug could benefit from a safety profile that is more familiar to regulators with fewer red flags. While pregnant women were excluded from the Merck trial due to a potential risk of birth defects, Pfizer’s drug did not have any similar restrictions. The Merck drug works by interfering with the coronavirus’ genetic code, a novel approach to disrupting the virus. Pfizer’s drug is part of a decades-old family of antiviral drugs known as protease inhibitors, which revolutionized the treatment of HIV and hepatitis C. The drugs block a key enzyme which viruses need to multiply in the human body. The drug was first identified during the SARS outbreak originating in Asia in 2003. Last year, company researchers decided to revive the medication and study it for COVID-19, given the similarities between the two coronaviruses. The U.S. has approved one other antiviral drug for COVID-19, remdesivir, and authorized three antibody therapies that help the immune system fight the virus. But they have to be given by IV or injection at hospitals or clinics, and limited supplies were strained by the last surge of the delta variant. Shares of Pfizer spiked more than 9% before the opening bell Friday. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

FDA OKs mixing COVID vaccines; backs Moderna, J&J boosters

U.S. regulators on Wednesday signed off on extending COVID-19 boosters to Americans who got the Moderna or Johnson & Johnson vaccine and said anyone eligible for an extra dose can get a brand different from the one they received initially. The Food and Drug Administration’s decisions mark a big step toward expanding the U.S. booster campaign, which began with extra doses of the Pfizer vaccine last month. But before more people roll up their sleeves, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will consult an expert panel Thursday before finalizing official recommendations for who should get boosters and when. The latest moves would expand by tens of millions the number of Americans eligible for boosters and formally allow “mixing and matching” of shots — making it simpler to get another dose, especially for people who had a side effect from one brand but still want the proven protection of vaccination. Specifically, the FDA authorized a third Moderna shot for seniors and others at high risk from COVID-19 because of their health problems, jobs, or living conditions — six months after their last shot. One big change: Moderna’s booster will be half the dose that’s used for the first two shots, based on company data showing that was plenty to rev up immunity again. For J&J’s single-shot vaccine, the FDA said all U.S. recipients, no matter their age, could get a second dose at least two months following their initial vaccination. The FDA rulings differ because the vaccines are made differently, with different dosing schedules — and the J&J vaccine has consistently shown a lower level of effectiveness than either of the two-shot Moderna and Pfizer vaccines. As for mixing and matching, the FDA said it’s OK to use any brand for the booster regardless of which vaccination people got first. The interchangeability of the shots is expected to speed the booster campaign, particularly in nursing homes and other institutional settings where residents have received different shots over time. FDA’s acting commissioner Dr. Janet Woodcock said the agency wanted to make its booster guidance as flexible as possible, given that many people don’t remember which brand they first received. In other cases, some people may want to try a different vaccine if they previously experienced common side effects like muscle ache or chills. Still, regulators said it’s likely many people will stick with the same vaccine brand. The decision was based on preliminary results from a government study of different booster combinations that showed an extra dose of any type revs up levels of virus-fighting antibodies. That study also showed recipients of the single-dose J&J vaccination had a far bigger response if they got a full-strength Moderna booster or a Pfizer booster rather than a second J&J shot. The study didn’t test the half-dose Moderna booster. Health authorities stress that the priority still is getting first shots to about 65 million eligible Americans who remain unvaccinated. But the booster campaign is meant to shore up protection against the virus amid signs that vaccine effectiveness is waning against mild infections, even though all three brands continue to protect against hospitalization and death. “Today the currently available data suggest waning immunity in some populations of fully vaccinated people,” Woodcock told reporters. “The availability of these authorized boosters is important for continued protection against COVID-19 disease.” The Moderna booster decision essentially matches FDA’s ruling that high-risk groups are eligible for the Pfizer vaccine, which is made with the same technology. FDA recommended that everyone who’d gotten the single-shot J&J vaccine get a booster since it has consistently shown lower protection than its two-shot rivals. And several independent FDA advisers who backed the booster decision suggested J&J’s vaccine should have originally been designed to require two doses. Experts continue to debate the rationale of the booster campaign. Some warn that the U.S. government hasn’t clearly articulated the goals of boosters given that the shots continue to head off the worst effects of COVID-19, and wonder if the aim is to tamp down on virus spread by curbing, at least temporarily, milder infections. FDA’s top vaccine official suggested regulators would move quickly to expand boosters to lower age groups, such as people in their 40s and 50s, if warranted. “We are watching this very closely and will take action as appropriate to make sure that the maximum protection is provided to the population,” said FDA’s Dr. Peter Marks. In August, the Biden administration announced plans for an across-the-board booster campaign aimed at all U.S. adults, but outside experts have repeatedly argued against such a sweeping effort. On Thursday an influential panel convened by the CDC is expected to offer more specifics on who should get boosters and when. Their recommendations are subject to approval by the CDC director. The vast majority of the nearly 190 million Americans who are fully vaccinated against COVID-19 have received the Pfizer or Moderna options, while about 15 million have received the J&J vaccine. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

White House details plan to vaccinate 28 million children age 5-11

Children ages 5 to 11 will soon be able to get a COVID-19 shot at their pediatrician’s office, local pharmacy, and potentially even their school, the White House said Wednesday as it detailed plans for the expected authorization of the Pfizer shot for elementary school youngsters in a matter of weeks. Federal regulators will meet over the next two weeks to weigh the safety and effectiveness of giving low-dose shots to the roughly 28 million children in that age group. Within hours of formal approval, which is expected after the Food and Drug Administration signs off and a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advisory panel meets on Nov. 2-3, millions of doses will begin going out to providers across the country, along with the smaller needles needed for injecting young children. Within days of that, the vaccine will be ready to go into arms on a wide scale. “We’re completing the operational planning to ensure vaccinations for kids ages 5 to 11 are available, easy and convenient,” White House COVID-19 coordinator Jeff Zients said. “We’re going to be ready, pending the FDA and CDC decision.” The Pfizer vaccine requires two doses three weeks apart and a two-week wait for full protection to kick in, meaning the first youngsters in line will be fully covered by Christmas. Some parents can hardly wait. Dr. Sterling Ransone said his rural Deltaville, Virginia, office is already getting calls from people asking for appointments for their children and saying, “I want my shot now.” “Judging by the number of calls, I think we’re going to be slammed for the first several weeks,” said Ransone, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians. Justin Shady, a film and TV writer in Chicago, said his 6-year-old daughter, Grey, got nervous when he told her she would be getting the shots soon. But he is bribing her with a trip to Disney World, and “she’s all in.” The family likes to travel, “we really just want to get back in the swing of seeing the world,” Shady said. As for youngsters under 5, Pfizer and Moderna are studying their vaccines in children down to 6 months old, with results expected later in the year. The Biden administration noted that the expansion of shots to children under 12 will not look like the start of the country’s vaccine rollout ten months ago when limited doses and inadequate capacity meant a painstaking wait for many Americans. The country now has ample supplies of the Pfizer shot to vaccinate the children who will soon be eligible, officials said, and they have been working for months to ensure widespread availability of shots. About 15 million doses will be shipped to providers across the U.S. in the first week after approval, the White House said. More than 25,000 pediatricians and primary care providers have already signed on to dispense the vaccine to elementary school children, the White House said, in addition to the tens of thousands of drugstores that are already administering shots to adults. Hundreds of school- and community-based clinics will also be funded and supported by the Federal Emergency Management Agency to help speed the process. In addition to doctors’ offices, schools are likely to be popular spots for the shots. In Maryland, state officials have offered to help schools set up vaccination clinics. Denver’s public schools plan to hold mass vaccination events for young children, along with smaller clinics offering shots during the school day and in the evenings. Chicago’s public health department is working closely with schools, which have already been hosting vaccination events for students age 12 and older and their families. The White House is also preparing a stepped-up campaign to educate parents and children about the safety of the shots and the ease of getting them. As has been the case for adult vaccinations, the administration believes trusted messengers — educators, doctors, and community leaders — will be vital to encouraging vaccinations. Dr. Lisa Reed, medical director for family medicine at MAHEC, a western North Carolina safety net provider that serves patients from rural Appalachia and more urban communities such as the tourist town of Asheville, said it is going to take effort to get some families on board. Reed said she lives “in a community that has a lot of vaccine hesitancy, unfortunately.” “Some have lower health literacy or belong to ethnic groups that are more hesitant in general” because of a history of mistrust, she said. And Asheville, she said, has a sizeable population of well-educated adults who are longtime vaccine skeptics. While children run a lower risk than older people of getting seriously ill from COVID-19, at least 637 people age 18 or under have died from the virus in the U.S., according to the CDC. Six million U.S. children have been infected, 1 million of them since early September amid the spread of the more contagious delta variant, the American Academy of Pediatrics says. Health officials believe that expanding the vaccine drive will not only curb the alarming number of infections in children but also reduce the spread of the virus to vulnerable adults. It could also help schools stay open, and youngsters get back on track academically, and contribute to the nation’s broader recovery from the pandemic. “COVID has also disrupted our kids’ lives. It’s made school harder, it’s disrupted their ability to see friends and family, it’s made youth sports more challenging,” U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy told NBC. “Getting our kids vaccinated, we have the prospect of protecting them, but also getting all of those activities back that are so important to our children.” Murthy said the administration, which is imposing vaccine mandates for millions of adults, is leaving it up to state and local officials to decide whether to require schoolchildren to get vaccinated. But he said such measures would be “a reasonable thing to consider.” “It’s also consistent with what we’ve done for other childhood vaccines, like measles, mumps, polio,” he said. The U.S. has

COVID-19 and pregnancy: Women regret not getting the vaccine

Sometimes when she’s feeding her infant daughter, Amanda Harrison is overcome with emotion and has to wipe away tears of gratitude. She is lucky to be here, holding her baby. Harrison was 29 weeks pregnant and unvaccinated when she got sick with COVID-19 in August. Her symptoms were mild at first, but she suddenly felt like she couldn’t breathe. Living in Phenix City, Alabama, she was intubated and flown to a hospital in Birmingham, where doctors delivered baby Lake two months early and put Harrison on life support. Kyndal Nipper, who hails from outside Columbus, Georgia, had only a brief bout with COVID-19 but a more tragic outcome. She was weeks away from giving birth in July when she lost her baby, a boy she and her husband planned to name Jack. Now Harrison and Nipper are sharing their stories in an attempt to persuade pregnant women to get COVID-19 vaccinations to protect themselves and their babies. Their warnings come amid a sharp increase in the number of severely ill pregnant women that led to 22 pregnant women dying from COVID in August, a one-month record. “We made a commitment that we would do anything in our power to educate and advocate for our boy because no other family should have to go through this,” Nipper said of herself and her husband. Harrison said she will “nicely argue to the bitter end” that pregnant women get vaccinated “because it could literally save your life.” Since the pandemic began, health officials have reported more than 125,000 cases and at least 161 deaths of pregnant women from COVID-19 in the U.S., according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And over the past several months, hospitals and doctors in virus hot spots have reported a sharp increase in the number of severely ill pregnant women. With just 31% of pregnant women nationwide vaccinated, the CDC issued an urgent advisory on Sept. 29 recommending that they get the shots. The agency cautioned that COVID-19 in pregnancy can cause preterm birth and other adverse outcomes and that stillbirths have been reported. Dr. Akila Subramaniam, an assistant professor in the maternal-fetal medicine division of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said the hospital saw a marked rise in the number of critically ill pregnant women during July and August. She said a study there found the delta variant of COVID-19 is associated with increased rates of severe disease in pregnant women and increased rates of preterm birth. “Is it because the delta variant is just more infectious or is it because delta is more severe? I don’t think we know the answer to that,” Subramaniam said. When COVID-19 vaccines became available to pregnant women in their states this spring, both Harrison, 36, and Nipper, 29, decided to wait. The shots didn’t have final approval from the Food and Drug Administration and pregnant women weren’t included in studies that led to emergency authorization, so initial guidance stopped short of fully recommending vaccination for them. Pfizer shots received formal approval in August. The women live on opposite sides of the Alabama-Georgia line, an area that was hit hard by the delta variant this summer. While Harrison had to be put on life support, Nipper’s symptoms were more subtle. When she was eight months pregnant, she lost her sense of smell and developed a fever. The symptoms went away quickly, but Jack didn’t seem to be kicking as much as he had been. She tried drinking a caffeinated beverage: Nothing. She headed to the hospital in Columbus, Georgia, for fetal monitoring where medical staff delivered the news: Baby Jack was gone. “He was supposed to come into the world in three weeks or less,” Nipper said. “And for them to tell you there’s no heartbeat and there is no movement …” Nipper’s doctor, Timothy Villegas, said testing showed the placenta itself was infected with the virus and displayed patterns of inflammation similar to the lungs of people who died of COVID-19. The infection likely caused the baby’s death by affecting its ability to get oxygen and nutrients, Villegas said. The doctor said he has since learned of similar cases from other physicians. “We’re at that point where everybody is starting to raise some red flags,” he said. In west Alabama, Dr. Cheree Melton, a family medicine physician who specializes in obstetrics and teaches at the University of Alabama, said she and her colleagues have had about a half-dozen unvaccinated patients infected with COVID-19 lose unborn children to either miscarriages or stillbirth, a problem that worsened with delta’s spread. “It’s absolutely heartbreaking to tell a mom that she will never get to hold her living child,” she said. “We have had to do that very often, more so than I remember doing over the last couple of years.” Melton said she encourages every unvaccinated pregnant woman she treats to get the shots, but that many haven’t. She said rumors and misinformation have been a problem. “I get everything from, ‘Well, somebody told me that it may cause me to be infertile in the future to, ‘It may harm my baby,’” she said. Nipper said she wishes she had asked more questions about the vaccine. “Looking back, I know I did everything that I could have possibly done to give him a healthy life,” she said. “The only thing I didn’t do, and I’ll have to carry with me, is I didn’t get the vaccine.” Now home from the hospital with a healthy baby, Harrison says she feels profound gratitude — tempered with survivor’s guilt. “I cry all the time. Just little things. Feeding her or hugging my 4-year-old. Just the thought of them having to go through life without me and that’s a lot of people’s reality right now,” Harrison said. “It was very scary and it all could have been prevented if I had gotten a vaccination.” Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Next on FDA’s agenda: Booster shots of Moderna, J&J vaccines

With many Americans who got Pfizer vaccinations already rolling up their sleeves for a booster shot, millions of others who received the Moderna or Johnson & Johnson vaccine wait anxiously to learn when it’s their turn. Federal regulators began tackling that question this week. On Thursday and Friday, the Food and Drug Administration convenes its independent advisers for the first stage in the process of deciding whether extra doses of the two vaccines should be dispensed and, if so, who should get them and when. The final go-ahead is not expected for at least another week. After the FDA advisers give their recommendation, the agency itself will make a decision on whether to authorize boosters. Then next week, a panel convened by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will offer more specifics on who should get them. Its decision is subject to approval by the CDC director. The process is meant to bolster public confidence in the vaccines. But it has already led to conflicts among experts and agencies — and documents the FDA released Tuesday suggest this week’s decisions will be equally difficult. In one earlier vaccine dispute, the CDC’s advisory panel last month backed Pfizer boosters at the six-month point for older Americans, nursing home residents, and people with underlying health problems. But CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky overruled her advisers and decided boosters should also be offered to those with high-risk jobs such as teachers and health care workers, adding tens of millions more Americans to the list. Some health experts fear the back-and-forth deliberations are muddling the public effort to persuade the unvaccinated to get their first shots. They worry that the talk of boosters will lead people to wrongly doubt the effectiveness of the vaccines in the first place. When the FDA’s panel meets to review the Moderna and J&J vaccines, experts will discuss whether a third Moderna shot should contain just half the original dose and what’s the best timing for a second shot of the single-dose J&J vaccine. The panel will also look into the safety and effectiveness of mixing and matching different brands of vaccine, something regulators have not endorsed so far. An estimated 103 million Americans are fully vaccinated with Pfizer’s formula, 69 million with Moderna’s, and 15 million with J&J’s, according to the CDC. Regulators took up the question of Pfizer boosters first because the company submitted its data ahead of the other vaccine makers. Tim Anderson, a U.S. history teacher at a high school outside Louisville, Kentucky, already had his two Moderna shots months before he came down with COVID-19 in August. While his symptoms hit him “like a sledgehammer,” he is convinced that the inoculation saved him and his girlfriend from the more severe effects of the disease. The two are now awaiting clearance of a Moderna booster shot. “Until we can build up enough immunity within our own self and, you know, as a group of humans, I’m willing to do what I need to do,” Anderson, 58, said. The FDA meetings come as U.S. vaccinations have climbed back above 1 million per day on average, an increase of more than 50% over the past two weeks. The rise has been driven mainly by Pfizer boosters and employer vaccine mandates. While the FDA and CDC so far have endorsed Pfizer boosters for specific groups only, Biden administration officials, including Dr. Anthony Fauci, have suggested that extra shots will eventually be recommended for most Americans. In a new review of Moderna’s data, the FDA did not indicate Tuesday if it was leaning toward clearing the company’s booster. It said vaccines used in the U.S. still provide protection, and it raised questions about some of Moderna’s data. The two initial Moderna shots contain 100 micrograms of vaccine each. But the drugmaker says 50 micrograms ought to be enough for a booster for healthy people. A company study of 344 people gave them a 50-microgram shot six months after their second dose, and levels of virus-fighting antibodies jumped. Moderna said the booster even triggered a 42-fold rise in antibodies able to target the extra-contagious delta variant. Side effects were similar to the fevers and aches that Moderna recipients commonly experience after their second regular shot, the company said. As for people who got the J&J vaccine, the company submitted data to the FDA for different options: a booster shot at two months or at six months. The company said in its FDA submission that a six-month booster is recommended but that a second dose could be given at two months in some situations. J&J released data in September showing that a booster given at two months provided 94% protection against moderate-to-severe COVID-19 infection. The company has not disclosed patient data on a six-month booster, but early measures of virus-fighting antibodies suggest it provides even higher protection. Even without a booster, J&J says, its vaccine remains about 80% effective at preventing COVID-19 hospitalizations in the U.S. Scientists emphasize that all three vaccines used in the U.S. still offer strong protection against severe disease and death from COVID-19. The issue is how quickly and how much protection against milder infection may wane. In one recent study, researchers compared about 14,000 people who had gotten their first Moderna dose a year ago with 11,000 vaccinated eight months ago. As the delta variant surged in July and August, the more recently vaccinated group had a 36% lower rate of “breakthrough” infections compared with those vaccinated longer ago. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

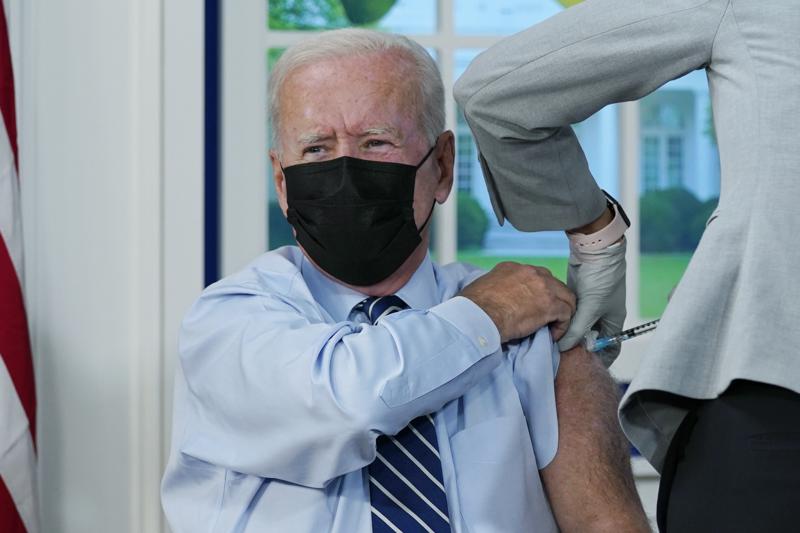

U.S. unveils guidance for federal vaccine mandate, exemptions

With just weeks remaining before federal workers must be vaccinated against COVID-19, the federal government on Monday outlined procedures for employees to request medical or religious exemptions from President Joe Biden’s mandate. The Office of Management and Budget released the new guidance Monday afternoon ahead of the Nov. 22 deadline for workers to be fully vaccinated, outlining specific medical conditions that would warrant an exemption. Under the guidelines, agencies are to direct workers to get their first shot within two weeks of an exemption request being denied or the resolution of a medical condition. They also make clear that federal agencies may deny medical or religious exemptions if they determine that no other safety protocol is adequate. The Biden administration is drawing on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidance to determine approved medical exemptions, including a history of allergic reaction to the vaccines. Other conditions, including being treated with monoclonal antibodies or having a history of multisystem inflammatory syndrome, warrant a 90-day delay in vaccination, in accordance with CDC advice. While the CDC recommends that women who are pregnant or are planning to become pregnant get vaccinated against COVID-19, the federal government will consider requests to delay vaccination while pregnant depending on the worker’s particular medical circumstances. Senior administration officials provided The Associated Press with a preview of the new guidance Monday before OMB posted it. Federal workers seeking exemptions will engage in what officials called an “interactive process” with their agencies, which will include being asked to provide documentation to support the exemption and potential accommodations. If an exemption request is rejected, workers will have two weeks to get a first shot or be subject to disciplinary proceedings in accordance with Biden’s order. Unvaccinated workers are required to wear masks and maintain social distancing and will have their ability to travel for work curtailed. New testing guidance for those who are granted exemptions is expected to be unveiled in the coming weeks. In some cases, agencies may deny even legitimate exemption requests if they determine “that no safety protocol other than vaccination is adequate” given the nature of the employee’s job. Under CDC guidelines, people are only considered fully vaccinated two weeks after their second dose of two-shot mRNA vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna or the one-dose Johnson & Johnson shot — meaning most federal workers have until Nov. 8, at the latest, to roll up their sleeves to comply with Biden’s order. According to the new federal guidance, neither past COVID-19 infection nor an antibody test can be substituted for vaccination. Meanwhile, private companies with more than 100 employees will be subject to a forthcoming rule from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration requiring all employees to be vaccinated or get tested weekly. Biden announced the regulation weeks ago, but the agency is still drafting the particulars. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.