GOP scrutiny of Black districts may deepen after court move

For decades, Democratic Rep. Al Lawson’s Florida district has stretched like a rubber band from Jacksonville to Tallahassee, scooping up as many Black voters as possible to comply with requirements that minority communities get grouped together so they can select their own leaders and flex their power in Washington. But the state’s Republican governor, Ron DeSantis, is taking the unusual step of asking Florida’s Supreme Court whether Lawson’s plurality-Black district can be broken up into whiter — and more Republican — districts. That type of request might typically face steep hurdles under state and federal laws that are meant to protect representation of marginalized communities in the nation’s politics. But the ground rules may be shifting after the U.S. Supreme Court sided this week with Republicans in Alabama to block efforts to ensure that Black voters are adequately represented in Congress by adding a second majority-Black district in the state. The ruling stunned civil rights groups, who have watched the court’s conservative majority steadily eat away at the Voting Rights Act for decades. While the law’s rules governing how to draw legislative lines based on race still stand, advocates worry the justices are prepared to act with renewed fervor to eliminate remaining protections in the landmark civil rights legislation. That, some worry, could embolden Republicans in places like Florida to take aim at districts like Lawson’s and ultimately reduce Black voters’ influence on Capitol Hill. “That has had an effect, as we’ve seen, on Black political power at all levels of government,” Kathryn Sadasivan, an NAACP Legal Defense Fund attorney who worked on the Alabama case, said of prior erosions of the Voting Rights Act. Republicans argue that the Alabama case is about providing clarity on redistricting rules. As it stands, mapmakers can be sued if they consider race too much but also if they fail to consider it the way the Voting Rights Act mandates and omit districts with certain shares of a minority population. “In the last 15 years, the court has said if race predominates, your map is going to be struck down, but if you don’t look” at race properly, you violate the Voting Rights Act, Jason Torchinsky, general counsel to the National Republican Redistricting Trust, said on a call with reporters on Wednesday. “The court has been very inconsistent with its guidance to legislators here, and we hope the Alabama decision brings some clarity.” Torchinsky is representing DeSantis in his case before the Florida Supreme Court and would not comment on the case. Republicans contend it is legally different from Alabama. The first hurdle is not the Voting Rights Act but rather Florida’s own state redistricting law, which prioritizes racial equity in similar ways. Torchinsky and other lawyers for DeSantis have argued that courts have to provide a clear legal standard for whether mapmakers can contort district lines in a quest for racial fairness. “After all,” Desantis’ attorneys wrote to the Florida Supreme Court of the rationale for Lawson’s district, “governmental actions based on race are presumptively unconstitutional.” The Florida case is becoming the latest test of how states’ court systems handle the politically charged redistricting battle. A decade ago, Florida’s Supreme Court struck down maps drawn by the state’s GOP-controlled Legislature because they violated the state’s ban on partisan redistricting. This cycle, the state Senate proposed maps that mostly kept the status quo in the state’s current 27 congressional seats while adding a 28th district that should favor Republicans. But, with Democrats doing better than expected in redistricting nationwide, DeSantis, a possible 2024 presidential contender, pushed for a more aggressive approach that could net the GOP three seats. But the state’s Supreme Court a decade ago was overwhelmingly Democratic. Now it’s dominated by Republican appointees. The question in Florida, said David Vicuna of the anti-gerrymandering group Common Cause, is “will courts put aside whatever are their own personal party preferences and adhere to the law?” Similar questions swirl around the nation’s highest court and its 6-3 conservative majority. Under the 1965 Voting Rights Act, mapmakers are required to draw districts with a plurality or majority of African Americans or other minority groups if they’re in a relatively compact area with a white population that votes starkly differently from them. For decades, the GOP went along with this approach because it led to states, particularly in the South, having a handful of districts packed with Democratic-leaning African American voters, leaving the remaining seats whiter and more Republican. But a series of adverse legal decisions over recent decades and increased Democratic aggressiveness have turned the tables. “Now we see kind of a flipping of this, where Democrats and voting rights plaintiffs are saying, ‘You have to create more majority-minority districts,’ and Republicans are saying, ‘Then we’re taking race too much into account,’” said Rick Hasen, a law professor at the University of California-Irvine. The issues came to a head in Alabama, where civil rights groups and Democrats joined forces to argue that the state’s GOP-drawn maps were unconstitutional because they packed most Black voters into only one of seven congressional districts. A three-judge panel agreed, potentially opening the door to similar new plurality-Black districts in states with similar demographics like Louisiana and South Carolina. But the Supreme Court on Monday stayed that order in a 5-4 decision, saying it would hear full arguments in its fall term and issue a ruling after that, presumably next year. Justice Elena Kagan, writing for two other dissenting liberal justices, warned that the court was already reinterpreting the Voting Rights Act by stopping the lower court’s order. Civil rights attorneys, while hopeful they can persuade the court’s six-justice conservative majority to maintain the standards they’ve used for decades, acknowledge that the Voting Rights Act has been hollowed out over the years. In 2013, the court ruled the federal government could no longer use the VRA to require certain states with a history of discrimination to run voting and map changes by the Justice Department first to ensure they’re not discriminatory. Two of the states that

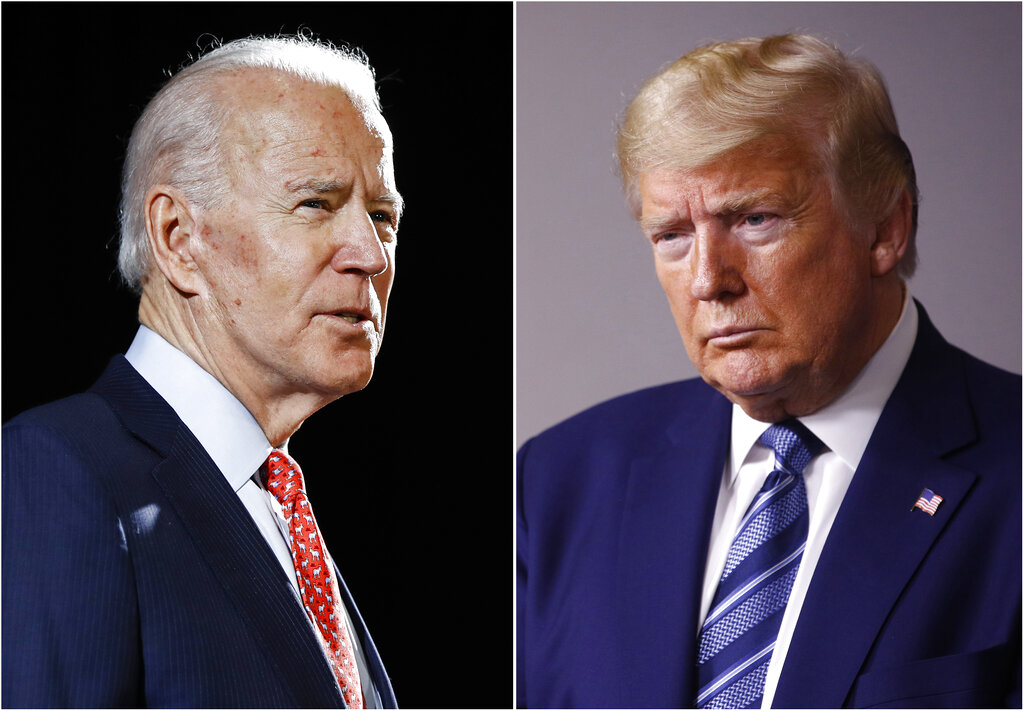

Presidency hinges on tight races in battleground states

The fate of the United States presidency hung in the balance Wednesday morning, as President Donald Trump and Democratic challenger Joe Biden battled for three familiar battleground states — Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania — that could prove crucial in determining who wins the White House. It was unclear when or how quickly a winner could be determined. A late burst of votes in Michigan and Wisconsin gave Biden a small lead in those states, but it was still too early to call the race. Hundreds of thousands of votes were also outstanding in Pennsylvania. The high stakes election was held against the backdrop of a historic pandemic that has killed more than 230,000 Americans and wiped away millions of jobs. Both candidates spent months pressing dramatically different visions for the nation’s future and voters responded in huge numbers, with more than 100 million people casting votes ahead of Election Day. But the margins were exceedingly tight, with the candidates trading wins in battleground states across the country. Trump picked up Florida, the largest of the swing states, while Biden flipped Arizona, a state that has reliably voted Republican in recent elections. Neither cleared the 270 Electoral College votes needed to carry the White House. Trump, in an extraordinary move from the White House, issued premature claims of victory and said he would take the election to the Supreme Court to stop the counting. It was unclear exactly what legal action he might try to pursue. Biden, briefly appearing in front of supporters in Delaware, urged patience, saying the election “ain’t over until every vote is counted, every ballot is counted.” “It’s not my place or Donald Trump’s place to declare who’s won this election,” Biden said. “That’s the decision of the American people.” Vote tabulations routinely continue beyond Election Day, and states largely set the rules for when the count has to end. In presidential elections, a key point is the date in December when presidential electors met. That’s set by federal law. Several states allow mailed-in votes to be accepted after Election Day, as long as they were postmarked by Tuesday. That includes Pennsylvania, where ballots postmarked by Nov. 3 can be accepted if they arrive up to three days after the election. Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf tweeted that his state had over 1 million ballots to be counted and that he “promised Pennsylvanians that we would count every vote and that’s what we’re going to do.” Trump appeared to suggest those ballots should not be counted, and that he would fight for that outcome at the high court. But legal experts were dubious of Trump’s declaration. “I do not see a way that he could go directly to the Supreme Court to stop the counting of votes. There could be fights in specific states, and some of those could end up at the Supreme Court. But this is not the way things work,” said Rick Hasen, a professor of law and political science at the University of California-Irvine. Trump has appointed three of the high court’s nine justices including, most recently, Amy Coney Barrett. Democrats typically outperform Republicans in mail voting, while the GOP looks to make up ground in Election Day turnout. That means the early margins between the candidates could be influenced by which type of votes — early or Election Day — were being reported by the states. Throughout the campaign, Trump cast doubt about the integrity of the election and repeatedly suggested that mail-in ballots should not be counted. Both campaigns had teams of lawyers at the ready to move into battleground states if there were legal challenges. The tight overall contest reflected a deeply polarized nation struggling to respond to the worst health crisis in more than a century, with millions of lost jobs, and a reckoning on racial injustice. Trump kept several states, including Texas, Iowa and Ohio, where Biden had made a strong play in the final stages of the campaign. But Biden also picked off states where Trump sought to compete, including New Hampshire and Minnesota. But Florida was the biggest, fiercely contested battleground on the map, with both campaigns battling over the 29 Electoral College votes that went to Trump. The president adopted Florida as his new home state, wooed its Latino community, particularly Cuban-Americans, and held rallies there incessantly. For his part, Biden deployed his top surrogate — President Barack Obama — there twice in the campaign’s closing days and benefitted from a $100 million pledge in the state from Michael Bloomberg. Democrats entered the night confident not only in Biden’s prospects, but also in the the party’s ability to take control of the Senate. But the GOP held several seats that were considered vulnerable, including in Iowa, Texas and Kansas. The House was expected to remain under Democratic control. The coronavirus pandemic — and Trump’s handling of it — was the inescapable focus for 2020. For Trump, the election stood as a judgment on his four years in office, a term in which he bent Washington to his will, challenged faith in its institutions and changed how America was viewed across the globe. Rarely trying to unite a country divided along lines of race and class, he has often acted as an insurgent against the government he led while undermining the nation’s scientists, bureaucracy and media. The momentum from early voting carried into Election Day, as an energized electorate produced long lines at polling sites throughout the country. Turnout was higher than in 2016 in numerous counties, including all of Florida, nearly every county in North Carolina and more than 100 counties in both Georgia and Texas. That tally seemed sure to increase as more counties reported their turnout figures. Voters braved worries of the coronavirus, threats of polling place intimidation and expectations of long lines caused by changes to voting systems, but appeared undeterred as turnout appeared it would easily surpass the 139 million ballots cast four years ago. No major problems arose on Tuesday, outside the typical glitches