U.S. Senate to vote on Respect for Marriage Act; several groups say it’s unconstitutional

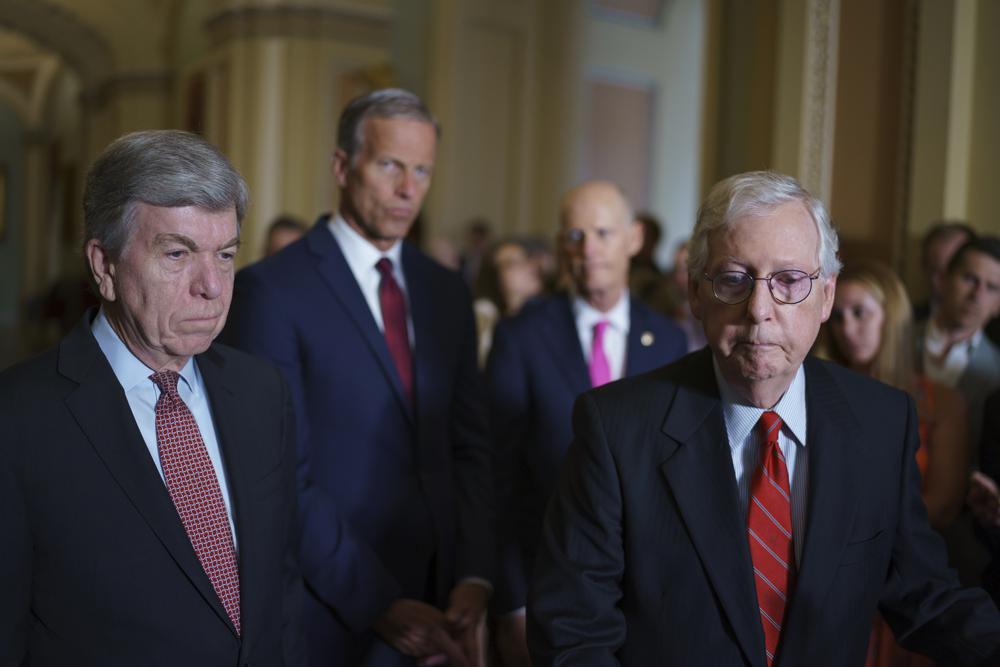

Several groups argue the Respect for Marriage Act (ROMA) currently before the U.S. Senate is unconstitutional and, if enacted, will eventually be struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court. The bill, HR 8404, was introduced in the House by U.S. Rep. Jerry Nadler, D-NY, on July 18 and passed by a vote of 267-157 the next day. The U.S. Senate took it up on Nov. 14. It would provide “statutory authority for same-sex and interracial marriages” and repeal several provisions of the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA). The 1996 law received bipartisan support, including from then U.S. Sen. Joe Biden and U.S. Rep. Chuck Schumer, D-NY, and from Democratic President Bill Clinton, who signed it. When a constitutional amendment was proposed to ban same-sex marriage in 2006, Sen. Biden told Meet the Press’s Tim Russert, “I can’t believe the American people can’t see through this. We already have a law, the Defense of Marriage Act … where I voted and others … that marriage is between a man and a woman, and states must respect that. … Why do we need a constitutional amendment? Marriage is between a man and a woman.” Sixteen years later, President Biden now supports replacing DOMA provisions, which “define, for purposes of federal law, marriage as between a man and a woman and spouse as a person of the opposite sex,” with ROMA provisions “that recognize any marriage that is valid under state law,” according to the bill summary. The summary also notes that the Supreme Court ruled three marriage-related laws as unconstitutional: DOMA (U.S. v. Windsor, 2013) and state laws banning same-sex marriage (Obergefell v. Hodges, 2015), and interracial marriage (Loving v. Virginia 1967). The bill would also allow “the Department of Justice to bring a civil action and establishes a private right of action for violations,” its summary states. When filing a cloture motion on a substitute amendment on Nov. 17, now Senate Majority Leader Schumer said the Senate would vote on ROMA when it returned on Monday after Thanksgiving. He said, “Let me be clear,” passing it “is not a matter of if but only when.” He also thanked his colleagues from both sides of the aisle “who led this bill.” Twelve Republicans voted with Democrats to allow it to move forward, eliminating a filibuster threat: Sens. Roy Blunt, Richard Burr, Shelley Capito, Susan Collins, Cynthia Lummis, Rob Portman, Mitt Romney, Dan Sullivan, Thom Tillis, Joni Ernst, Lisa Murkowski, and Todd Young. After their vote, Biden said, “Love is love, and Americans should have the right to marry the person they love,” adding their vote made “the United States one step closer to protecting that right in law.” Schumer also said he had “zero doubt” the bill “will soon be law of the land.” But multiple groups disagree, arguing it’s unconstitutional for the same reasons the Supreme Court struck down DOMA. Because the court already ruled Congress doesn’t have the constitutional authority to define marriage under Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution, and because ROMA is nearly identical to DOMA, they argue it will also likely be struck down. In a letter to Congress, the nonprofit religious freedom organization Liberty Counsel argues the court ruled in Windsor, “DOMA, because of its reach and extent, departs from this history and tradition of reliance on state law to define marriage.” It also ruled, “[b]y history and tradition the definition and regulation of marriage . . . has been treated as being within the authority and realm of the separate States.” Liberty Counsel Founder and Chairman Mat Staver, said, “The Constitution cannot be said to prohibit the exercise of power to define marriage in one manner yet authorize the opposite definition of that same unconstitutional exercise of power. If Windsor noted that Congress lacked authority in this realm, then it necessarily lacks the power here.” While a bipartisan amendment was introduced claiming to protect religious liberty, Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, argues it really doesn’t. “Religious Americans will be subject to potentially ruinous litigation, while the tax-exempt status of certain charitable organizations, educational institutions, and non-profits will be threatened. My amendment would have shored up these vulnerabilities,” he said. Heritage Foundation President Kevin Roberts said, “Conservatives are deeply disappointed by the betrayal of Senate Republicans to protect Americans’ religious freedom and won’t soon forget the votes of the 12 Republican senators who cast aside an essential right in a bill that will weaponize the federal government against believers of nearly every major religion.” Gregory Baylor, senior counsel with Alliance for Defending Freedom, also said the law is “unnecessary and could have a disastrous effect on religious freedom. While proponents of the bill claim that it simply codifies the 2015 Obergefell decision, in reality, it is an intentional attack on the religious freedom of millions of Americans with sincerely held beliefs about marriage.” It also “threatens religious freedom and the institution of marriage” by codifying a “false definition of marriage in the American legal fabric,” ADF argues. It also “opens the door to federal recognition of polygamous relationships, jeopardizes the tax-exempt status of nonprofits that exercise their belief that marriage is the union of one man and one woman, and endangers faith-based social-service organizations by threatening litigation and liability risk if they follow their views on marriage when working with the government.” Republished with the permission of The Center Square.

U.S. Senate is focus of politicos across the country

In Alabama, with hours left in the 2022 election cycle, the Republican nominee for U.S. Senate, Katie Britt, appears to be a prohibitive favorite over Democratic nominee Dr. Will Boyd and Libertarian nominee John Sophocleus for the open U.S. Senate seat, currently held by the retiring Richard Shelby. Nationally, though, there is intense speculation over what could happen on election day on Tuesday and which party will control the next Congress. Polling shows Republicans with growing momentum, and it appears almost a certainty that the GOP will take control of the U.S. House of Representatives after four years of Nancy Pelosi’s leadership, and it does not appear to even be close. Real Clear Politics does not see any of Alabama’s Seven Congressional Districts as even being in play in this election. With the House effectively lost to them, Democrats have focused their efforts on maintaining their narrow control of the U.S. Senate, which for the past two years has been tied 50 to 50; but Vice President Kamala Harris gives the Democrats control of the body. Democrats had staked their hopes on the Select Committee on January 6, and the abortion issue to energize their base. That has not happened. Instead, Republicans are running on inflation, crime, the border, and economic issues, and that strategy appears to be playing well with voters. It is too close to call who will control the Senate before the votes are counted, but clearly, the trend has been moving in favor of the GOP in the last three weeks. The best opportunity for a Republican pickup appears to be Nevada. There, the Republican challenger, former state Attorney General Adam Laxalt, is leading Democratic incumbent Sen. Catharine Masto in recent polling. The latest Real Clear Politics rolling poll average has Laxalt leading Masto by 1.9 points. The best opportunity for a Democratic pickup appears to be Pennsylvania, where Republican incumbent Sen. Pat Toomey is retiring even though he is only 60 years old. Toomey’s controversial vote in 2021 to convict former President Donald Trump of inciting the January 6 insurrection made his ability to win a Republican primary unlikely. Democratic lieutenant Governor John Fetterman had appeared to have an insurmountable lead over Republican nominee television host Dr. Mehmet Oz, but that lead has evaporated. The race is now a tossup, but Oz has the momentum after clearly besting Fetterman in the debate. Presidents Barack Obama and Joe Biden are both campaigning hard for Fetterman, and Trump is campaigning for Oz. Both parties recognize that there is little chance of the Democrats holding on to the Senate if Pennsylvania falls to the GOP. Georgia is a tossup between Democratic incumbent Sen. Raphael Warnock and college football star Republican challenger Hershel Walker, but Walker clearly has the momentum in this race. Due to Georgia’s election rules, however, this race will likely go to a December runoff. Warnock is being dragged down in the general election by the terrible performance of Democratic gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams. Brian Kemp is sure to best Abrams on Tuesday. If Walker faces Warnock again on December 6, however, will those Kemp voters come out to help the Republicans lift Walker over Warnock? The trifecta of Pennsylvania, Nevada, and Georgia likely decide the Senate, but there are other races where Democratic incumbents are fighting for their political lives. In New Hampshire, Democratic incumbent Sen. Maggie Hassan is leading Republican challenger Dan Bolduc, but this race is much closer at this point than politicos expected this summer. If there really is a Republican “red wave” where GOP voters come out to the polls on Tuesday with more enthusiasm than Democrats, then the Granite state could easily swing to the GOP. According to the latest Real Clear Politics rolling poll average, Hassan has a lead of just .8 – well inside the margin of error and trending in the wrong direction for Hassan. Another state where a “red wave” could unseat a Democratic incumbent is Arizona. This summer, it appeared that incumbent former astronaut and the husband of former Congresswoman Gabby Giffords, Sen. Mark Kelly, would win easy reelection by more than ten points. Now this race is much closer than even the most enthusiastic GOP supporters thought possible. Republican nominee Blake Masters has won over a lot of voters. If the GOP candidate for Governor wins and wins big, Arizona could be a surprise U.S. Senate pickup for the GOP. This race has been a tie in two of the last 5 polls, with Kelly’s best performance being plus three in a Marist poll. Both Remington and Fox News have Kelly leading by just one point. If Republicans flip Arizona, there is little likelihood of the Democrats holding on to the Senate. In the summer, the Democrats believed that Republican incumbent Ron Johnson in Wisconsin was very vulnerable. Those hopes are fading fast as Johnson is surging in the polls over Democratic challenger Lt. Gov. Mandela Barnes. Senate colleague Bernie Sanders is on the ground campaigning for Barnes this weekend. Johnson leads Barnes by 3.2 points in the most recent Real Clear Politics rolling average. If there is no GOP wave, this could be closer than the polls indicate, and a Barnes upset win is still not outside the realm of possibility. In Washington state, even Republicans were expecting incumbent Sen. Patty Murray to coast to another easy re-election. That race is now much closer than anyone had previously thought possible. Republican challenger Tiffany Smiley has pushed Murray far harder than anyone could have anticipated in this blue state. Murray was consistently polling nine points or more in September, but recent polling has shown her lead shrink to just 1 to 4 points. The Real Clear Politics still has Murray up by 3.0 points in their most recent polling average, but that has dropped from 9 points just four weeks ago. This would still be an unlikely pickup for Republicans in a state that Biden won by 19.2 points just two years ago. That said, a Smiley victory is now within the margin of error in some recent polling. Murray holding on to her seat remains the most likely outcome, but that is now far from certain. In North Carolina, Republican incumbent Sen. Richard Burr is retiring. This seemed to be an opportunity for Democrats to flip this red seat blue, and Civitas/Cygnal had the race between Republican Ted Budd and Democratic nominee Cheri Beasley tied as recently as September 26, but Budd appears to

Joe Biden finds no respite at home after returning from Europe

With the last nine unscripted words of an impassioned speech about Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, President Joe Biden created a troubling distraction, undermining his effectiveness as he returned home to face restive Americans who strongly disapprove of his performance on issues that matter most to them. His comment that Russia’s Vladimir Putin “cannot remain in power” — an assertion that his aides were forced to quickly clean up — overshadowed his larger message of solidifying the Western coalition that’s confronting Moscow. It punctuated another frustrating moment for an administration that’s struggled to regain its footing — and the American electorate’s support — in the face of an ongoing pandemic, escalating inflation, and an increasingly complicated foreign policy crisis that raises the specter of nuclear conflict. Although he’s forged a united front to punish Russia with sanctions for the invasion of Ukraine, polls show Americans feel no better about his leadership as the bloody war continues. Meanwhile, Democrats are in danger of losing control of Congress in November’s midterm elections, leaving Biden with limited opportunities to advance a progressive domestic agenda that remains stalled. The president is on the verge of securing the confirmation of the first Black woman, Ketanji Brown Jackson, on the U.S. Supreme Court, yet there’s no clear path forward for him to fulfill other campaign promises around voting rights, criminal justice reform, and fighting climate change. While polls show that Jackson is broadly supported by Americans, it hasn’t helped improve Biden’s standing with voters less than eight months before the midterms, which Republicans hope to frame as a referendum on the president. The war in Russia has consumed much of the White House’s messaging bandwidth, but Biden is looking to turn the spotlight onto some of his domestic priorities this week. He is expected to unveil a new budget proposal on Monday, which includes a renewed focus on cutting the federal deficit and a populist proposal to increase taxes on the wealthiest Americans. If approved by Congress — far from a certainty — households worth more than $100 million — a measurement of wealth, not income — would have to pay a minimum tax of 20% on their earnings. The added revenue could help keep the deficit in check and finance some of Biden’s domestic priorities, including expanded safety net programs. There are few if any signs of Republican support for the proposal so far, and even some Democrats have been lukewarm to the idea. Biden’s case isn’t helped by his approval ratings. A slim 34% of Americans think Biden is doing a good job handling the economy, which is normally the top issue for voters in an election year, according to a poll released Thursday by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. His contentious assertion about Putin in his Warsaw speech did little to help things. The White House rushed to clarify that Biden wasn’t actually calling for “regime change,” but by the next day, it became clear that the dramatic statement had produced some of the first overt cracks in unity among NATO nations that had just convened in Brussels for an emergency meeting. Some leading Western European allies, including France and Germany, tend to be more cautious than the U.S. about how to confront Russia. Until Saturday night, Biden had calibrated his words carefully. French President Emmanuel Macron said Biden’s remarks could make it harder to resolve the conflict. “I wouldn’t use those terms because I continue to speak to President Putin, because what do we want to do collectively?” he said. “We want to stop the war that Russia launched in Ukraine, without waging war and without escalation.” In Berlin, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz said Sunday that neither NATO nor Biden seek regime change in Russia. Asked about Biden’s remarks during an appearance on ARD television, Scholz also said Biden had not made a dangerous mistake. “We both agree completely that regime change is not an object and aim of policy that we pursue together,” the chancellor said. Biden has enjoyed some rare bipartisan support for his handling of the Ukraine crisis. But some Republicans who have been generally supportive of his approach to the crisis chided him for his comments. Sen. James Risch of Idaho, the top Republican on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, dryly noted on CNN’s “State of the Union” on Sunday, “Please, Mr. President, stay on script.” Sen. Rob Portman, R-Ohio, told NBC’s “Meet the Press” that Biden’s final comment “plays into the hands of the Russian propagandists and plays into the hands of Vladimir Putin.” Secretary of State Antony Blinken was forced to continue clarifying Biden’s speech during a trip through the Middle East, where he had intended to focus on solidifying American partnerships as the administration seeks a renewed nuclear agreement with Iran. Speaking at a news conference in Jerusalem, Blinken said Biden meant that “Putin cannot be empowered to wage war or engage in aggression against Ukraine or anyone else.” In case there was any doubt, Biden gave an emphatic “No!” when asked by a reporter outside of church Sunday if he was calling for regime change with the remark. Even as Biden seemed to go too far for some allies with his speech, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy seemed to draw little comfort from it. He accused Western nations of lacking courage to confront Russia, and he said criticized their “ping-pong about who and how should hand over jets” and other weapons to the Ukrainian military. The speech in Warsaw was the third, and by far most consequential, of instances from the trip where Biden’s aides needed to clean up his comments. During a news conference in Brussels on Thursday, he said the U.S. would respond “in-kind” if Putin used chemical weapons in Ukraine. The next day, national security advisor Jake Sullivan said the president meant that “we’ll respond accordingly,” not that the U.S. would use chemical weapons of its own. And then, while speaking to members of the 82nd Airborne Division soldiers recently deployed to Poland, Biden seemed to suggest they would be going to Ukraine.

Congress passes bill to shore up Postal Service, delivery

Congress on Tuesday passed legislation that would shore up the U.S. Postal Service and ensure six-day-a-week mail delivery, sending the bill to President Joe Biden to sign into law. The long-fought postal overhaul has been years in the making and comes amid widespread complaints about mail service slowdowns. Many Americans became dependent on the Postal Service during the COVID-19 crisis, but officials have repeatedly warned that without congressional action, it would run out of cash by 2024. “The post office usually delivers for us, but today we’re going to deliver for them,” said Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y. Congress mustered rare bipartisan support for the Postal Service package, dropping some of the more controversial proposals to settle on core ways to save the service and ensure its future operations. Last month, the House approved the bill, 342-92, with all Democrats and most Republicans voting for it. On Tuesday, the Senate sent it to Biden’s desk on a 79-19 vote. Republican Sen. Jerry Moran said the Postal Service has been in a “death spiral” that is particularly hard on rural Americans, including in his state of Kansas, as post offices shuttered and services were cut. “Smart reforms were needed,” he said. The Postal Service Reform Act would lift unusual budget requirements that have contributed to the Postal Service’s red ink and would set in law the requirement that the mail is delivered six days a week, except in the case of federal holidays, natural disasters, and a few other situations. Postage sales and other services were supposed to sustain the Postal Service, but it has suffered 14 straight years of losses. Growing workers’ compensation and benefit costs, plus steady declines in mail volume, have contributed to the red ink, even as the Postal Service delivers to 1 million additional locations every year. The bill would end a requirement that the Postal Service finance workers’ health care benefits ahead of time for the next 75 years, an obligation that private companies and federal agencies do not face. Instead, the Postal Service would require future retirees to enroll in Medicare and would pay current retirees’ actual health care costs that aren’t covered by the federal health insurance program for older people. Gone for now are ideas for cutting back on mail delivery, which had become politically toxic. Also set aside, for now, are other proposals that have been floated over the years to change postal operations, including those to privatize some services. Sen. Gary Peters, D-Mich., the chairman of the Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, helmed the legislation and said that since the nation’s founding, the Postal Service has become “a vital part of the fabric of our nation.” Peters said the legislation would ensure the Postal Service can continue its nearly “250-year tradition of delivering service to the American people.” Beyond cards and letters, people rely on the post office to deliver government checks, prescription drugs, and many goods purchased online but ultimately delivered to doorsteps and mailboxes by the Postal Service. “We need to save our Postal Service,” said Sen. Rob Portman, R-Ohio, another architect of the bill. Portman said the bill is not a bailout, and no new funding is going to the agency. Criticism of the Postal Service peaked in 2020, ahead of the presidential election, as cutbacks delayed service at a time when millions of Americans were relying on mail-in ballots during the first year of the COVID-19 crisis. At the time, President Donald Trump acknowledged he was trying to starve the Postal Service of money to make it harder to process an expected surge of mail-in ballots, which he worried could cost him the election. Dominated by Trump appointees, the agency’s board of governors had tapped Louis DeJoy, a major GOP donor, as the new postmaster general. He proposed a 10-year plan to stabilize the service’s finances with steps like additional mail slowdowns, cutting some offices’ hours, and perhaps higher rates. To measure the Postal Service’s progress at improving its service, the bill would also require it to set up an online “dashboard” that would be searchable by ZIP code to show how long it takes to deliver letters and packages. The legislation approved by Congress is supported by Biden, the Postal Service, postal worker unions, and others. Mark Dimondstein, the president of the American Postal Workers Union, called passage of the legislation a “turning point in the fight to protect and strengthen the people’s public postal service, a national treasure.” Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Analysis: Republicans poised to do well in 2022 midterm elections

Less than a year out from the November 2022 midterm elections, Republicans are in a position to pick up more seats than previously expected after redistricting was finalized across the states and 44 members of Congress, a majority of them Democrats, are either retiring or aren’t running for reelection. Skyrocketing inflation and energy costs and President Joe Biden’s declining polling numbers could result in Democrats losing dozens of Congressional seats, political analysts indicate. As of this month, six sitting members of the U.S. Senate and 38 in the U.S. House are leaving office, according to calculations by Ballotpedia. Of the 37 leaving the U.S. House, 26 are Democrats and 12 are Republicans. The majority – 28 – are retiring. They include six senators, five of whom are Republicans, and 22 representatives, 17 of whom are Democrats. The remainder, 15, are running for another office. Eight House members are running for a U.S. Senate seat, evenly split among Republicans and Democrats, with four each. They are from Vermont, Pennsylvania, Missouri, Florida, North Carolina, Ohio, and Alabama. Three House members are running for governor – one Democrat and one Republican in New York, and one Democrat in Florida. Others are running for state and local offices in Texas, Maryland, California, and Georgia. They include one Republican running for secretary of state, one Republican and one Democrat running for attorney general, and one Democrat running for mayor. No U.S. Senator is running for another office; all six are retiring. They include Republicans Richard Burr of North Carolina, Pat Toomey of Pennsylvania, Rob Portman of Ohio, Richard Shelby of Alabama, Roy Blunt of Missouri, and Democrat Patrick Leahy of Vermont. A Washington Post/ABC News poll found that Republicans hold a 10-point margin over Democrats in a generic congressional race. Biden’s approval rating on the economy was 39%, and his overall approval rating was 41% at the time. A December Rasmussen Reports survey also found that voters favored Republicans over Democrats by 13 points, 51%-38%, at the time. An even wider margin of 22% was found among voters who identify as Independents, who said they would choose a generic Republican over a generic Democrat by a margin of 48%-26%. Currently, Democrats hold a nine-seat majority in the U.S. House. The U.S. Senate is split, with 50 Republicans, 48 Democrats and 2 Independents, with the Independents caucusing with the Democrats, and the Democratic vice president acting as a tie breaker. This could change with West Virginia Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin considering leaving the Democratic Party. “I would like to hope that there are still Democrats that feel like I do,” Manchin told a local West Virginia radio station, as reported by the Washington Post. “Now, if there’s no Democrats like that, then they’ll have to push me wherever they want me.” Manchin also told reporters last month that he’d consider leaving the Democratic Party if he were to become “an embarrassment to my Democrat colleagues,” as a “moderate centrist Democrat.” He said he’d still caucus with the Democrats, enabling them to keep the majority temporarily. Historically, since the end of World War II, the sitting president’s party has lost seats nearly every midterm election. A total of 469 seats in Congress are up for reelection in 2022, including 34 in the Senate and all 435 in the House. As a result of changing demographics reported by the 2020 Census, six states gained congressional seats, with Texas gaining two. Five states gained one seat: Colorado, Florida, Montana, North Carolina, and Oregon. Seven states lost a seat: California, Illinois, Michigan, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. By Bethany Blankley | The Center Square contributor Republished with the permission of The Center Square.

Joe Biden signs $1T infrastructure deal with bipartisan crowd

President Joe Biden signed his hard-fought $1 trillion infrastructure deal into law Monday before a bipartisan, celebratory crowd on the White House lawn, declaring that the new infusion of cash for roads, bridges, ports, and more is going to make life “change for the better” for the American people. But prospects are tougher for further bipartisanship ahead of the 2022 midterm elections as Biden pivots back to more difficult negotiations over his broader $1.85 trillion social spending package. The president hopes to use the infrastructure law to build back his popularity, which has taken a hit amid rising inflation and the inability to fully shake the public health and economic risks from COVID-19. “My message to the American people is this: America is moving again and your life is going to change for the better,” he said. With the bipartisan deal, the president had to choose between his promise of fostering national unity and a commitment to transformative change. The final measure whittled down much of his initial vision for infrastructure. Yet the administration hopes to sell the new law as a success that bridged partisan divides and will elevate the country with clean drinking water, high-speed internet, and a shift away from fossil fuels. “Folks, too often in Washington, the reason we didn’t get things done is because we insisted on getting everything we want. Everything,” Biden said. “With this law, we focused on getting things done. I ran for president because the only way to move our country forward in my view was through compromise and consensus.” Biden will get outside Washington to sell the plan more broadly in the coming days. He intends to go to New Hampshire on Tuesday to visit a bridge on the state’s “red list” for repair, and he will go to Detroit on Wednesday for a stop at General Motors’ electric vehicle assembly plant, while other officials also fan out across the country. The president went to the Port of Baltimore last week to highlight how the supply chain investments from the law could limit inflation and strengthen supply chains, a key concern of voters who are dealing with higher prices. “We see this as is an opportunity because we know that the president’s agenda is quite popular,” White House press secretary Jen Psaki said Monday before the signing. The outreach to voters can move “beyond the legislative process to talk about how this is going to help them. And we’re hoping that’s going to have an impact.” Biden held off on signing the hard-fought infrastructure deal after it passed on Nov. 5 until legislators would be back from a congressional recess and could join in a splashy bipartisan event. On Sunday night before the signing, the White House announced Mitch Landrieu, the former New Orleans mayor, would help manage and coordinate the implementation of the infrastructure spending. The gathering Monday on the White House lawn was uniquely upbeat with a brass band and peppy speeches, a contrast to the drama and tensions when the fate of the package was in doubt for several months. The speakers lauded the measure for creating jobs, combating inflation, and responding to the needs of voters. Ohio Sen. Rob Portman, a Republican who helped negotiate the package, celebrated Biden’s willingness to jettison much of his initial proposal to help bring GOP lawmakers on board. Portman even credited former President Donald Trump for raising awareness about infrastructure, even though the loser of the 2020 election voiced intense opposition to the ultimate agreement. “This bipartisan support for this bill comes because it makes sense for our constituents, but the approach from the center out should be the norm, not the exception,” Portman said. The signing included governors and mayors of both parties and labor and business leaders. In addition to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, the guest list included Republicans such as Louisiana Sen. Bill Cassidy, Maine Sen. Susan Collins, New York Rep. Tom Reed, Alaska Rep. Don Young, and Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan. In order to achieve a bipartisan deal, the president had to cut back his initial ambition to spend $2.3 trillion on infrastructure by more than half. The bill that becomes law on Monday in reality includes about $550 billion in new spending over 10 years, since some of the expenditures in the package were already planned. The agreement ultimately got support from 19 Senate Republicans, including Senate GOP leader Mitch McConnell. Thirteen House Republicans also voted for the infrastructure bill. An angry Trump issued a statement attacking “Old Crow” McConnell and other Republicans for cooperating on “a terrible Democrat Socialist Infrastructure Plan.” McConnell said the country “desperately needs” the new infrastructure money, but he skipped Monday’s signing ceremony, telling WHAS radio in Louisville, Kentucky, that he had “other things” to do. Historians, economists, and engineers interviewed by The Associated Press welcomed Biden’s efforts. But they stressed that $1 trillion was not nearly enough to overcome the government’s failure for decades to maintain and upgrade the country’s infrastructure. The politics essentially forced a trade-off in terms of potential impact not just on the climate but on the ability to outpace the rest of the world this century and remain the dominant economic power. “We’ve got to be sober here about what our infrastructure gap is in terms of a level of investment and go into this eyes wide open, that this is not going to solve our infrastructure problems across the nation,” said David Van Slyke, dean of the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University. Biden also tried unsuccessfully to tie the infrastructure package to the passage of a broader package of $1.85 trillion in proposed spending on families, health care, and a shift to renewable energy that could help address climate change. That measure has yet to gain sufficient support from the narrow Democratic majorities in the Senate and House. Biden continues to work to appease Democratic skeptics of the broader package such as

Big win for $1T infrastructure bill: Dems, GOP come together

With a robust vote after weeks of fits and starts, the Senate approved a $1 trillion infrastructure plan for states coast to coast on Tuesday, as a rare coalition of Democrats and Republicans joined together to overcome skeptics and deliver a cornerstone of President Joe Biden’s agenda. “Today, we proved that democracy can still work,” Biden declared at the White House, noting that the 69-30 vote included even Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell. “We can still come together to do big things, important things, for the American people,” Biden said. The overwhelming tally provided fresh momentum for the first phase of Biden’s “Build Back Better” priorities, now heading to the House. A sizable number of lawmakers showed they were willing to set aside partisan pressures, at least for a moment, eager to send billions to their states for rebuilding roads, broadband internet, water pipes, and the public works systems that underpin much of American life. The vote also set the stage for a much more contentious fight over Biden’s bigger $3.5 trillion package that is next up in the Senate — a more liberal undertaking of child care, elder care, and other programs that is much more partisan and expected to draw only Democratic support. That debate is expected to extend into the fall. With the Republicans lockstep against the next big package, many of them reached for the current compromise with the White House because they, too, wanted to show they could deliver and the government could function. “Today’s kind of a good news, bad news day,” said Alaska Sen. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, one of the negotiators. “The good news is that today we really did something historic in the United States Senate; we moved out an infrastructure package, something that we have talked about doing for years.” The bad news, she said, is what’s coming next. Infrastructure was once a mainstay of lawmaking, but the weeks-long slog to strike a compromise showed how hard it has become for Congress to tackle routine legislating, even on shared priorities. Tuesday’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act started with a group of 10 senators who seized on Biden’s campaign promise to draft a scaled-down version of his initial $2.3 trillion proposal, one that could more broadly appeal to both parties in the narrowly divided Congress, especially the 50-50 Senate. It swelled to a 2,700-page bill backed by the president and also business, labor, and farm interests. Over time, it drew an expansive alliance of senators and a bipartisan group in the House. In all, 19 Republicans joined all Democrats in voting for Senate passage. Vice President Kamala Harris, as presiding officer, announced the final tally. While liberal lawmakers said the package doesn’t go far enough as a down-payment on Biden’s priorities and conservatives said it is too costly and should be more fully paid for, the coalition of centrist senators was able to hold. Even broadsides from former President Donald Trump could not bring the bill down. The measure proposes nearly $550 billion in new spending over five years in addition to current federal authorizations for public works that will reach virtually every corner of the country — a potentially historic expenditure Biden has put on par with the building of the transcontinental railroad and Interstate highway system. There’s money to rebuild roads and bridges and also to shore up coastlines against climate change, protect public utility systems from cyberattacks and modernize the electric grid. Public transit gets a boost, as do airports and freight rail. Most lead drinking water pipes in America could be replaced. Sen. Rob Portman of Ohio, the lead Republican negotiator, said the work “demonstrates to the American people that we can get our act together on a bipartisan basis to get something done.” The top Democratic negotiator, Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, said rarely will a piece of legislation affect so many Americans. She gave a nod to the late fellow Arizona Sen. John McCain and said she was trying to follow his example to “reach bipartisan agreements that try to bring the country together.” Drafted during the COVID-19 crisis, the bill would provide $65 billion for broadband, a provision Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, negotiated because she said the coronavirus pandemic showed that such service “is no longer a luxury; it is a necessity.” States will receive money to expand broadband and make it more affordable. Despite the momentum, action slowed last weekend when Sen. Bill Hagerty, a Tennessee Republican allied with Trump, refused to speed up the process. Trump had called his one-time Japan ambassador and cheered him on, but it’s unclear if the former president’s views still carry as much sway with most senators. Trump issued fresh complaints hours before Tuesday’s vote. He had tried and failed to pass his own infrastructure bill during his time in the White House. Other Republican senators objected to the size, scope, and financing of the package, particularly concerned after the Congressional Budget Office said it would add $256 billion to deficits over the decade. Rather than pressure his colleagues, Senate Republican leader McConnell of Kentucky stayed behind the scenes for much of the bipartisan work. He allowed the voting to proceed and may benefit from enabling this package in a stroke of bipartisanship while trying to stop Biden’s next big effort. Unlike the $3.5 trillion second package, which would be paid for by higher tax rates for corporations and the wealthy, the bipartisan measure is to be funded by repurposing other money, including some COVID-19 aid. The bill’s backers argue that the budget office’s analysis was unable to take into account certain revenue streams that will help offset its costs — including from future economic growth. Senators have spent the past week processing nearly two dozen amendments, but none substantially changed the framework. The House is expected to consider both Biden infrastructure packages together, but centrist lawmakers urged Speaker Nancy Pelosi to bring the bipartisan plan forward quickly, and they raised concerns about the bigger bill in a sign of the complicated politics still ahead. After the Senate vote, she declared, “Today is a day of progress … a once in a century opportunity.”

Infrastructure on track as bipartisan Senate coalition grows

After weeks of fits, starts, and delays, the Senate is on track to give final approval to the $1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure plan, with a growing coalition of Democrats and Republicans prepared to lift the first phase of President Joe Biden’s rebuilding agenda to passage. Final Senate votes are expected Tuesday, and the bill would then go to the House. All told, some 70 senators appear poised to carry the bipartisan package to passage, a potentially robust tally of lawmakers eager to tap the billions in new spending for their states and to show voters back home they can deliver. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer said it’s “the first time the Senate has come together around such a package in decades.” The often elusive political center is holding steady, a rare partnership with Biden’s White House. On the left, the Democrats have withstood the complaints of liberals who say the proposal falls short of what’s needed to provide a down payment on one of the president’s top priorities. From the right, the Republicans are largely ignoring the criticism from their most conservative and far-flung voices, including a barrage of name-calling from former President Donald Trump as he tries to derail the package. Together, a sizable number of business, farm, and labor groups back the package, which proposes nearly $550 billion in new spending on what are typically mainstays of federal spending — roads, bridges, broadband internet, water pipes, and other public works systems that cities and states often cannot afford on their own. “This has been a different sort of process,” said Sen. Rob Portman of Ohio, the lead Republican negotiator of the group of 10 senators who drafted the package. Portman, a former White House budget director for George W. Bush, said the investments being made have been talked about for years yet never seem to get done. He said, “We’ll be getting it right for the American people.” The top Democratic negotiator, Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, said she was trying to follow the example of fellow Arizonan John McCain to “reach bipartisan agreements that try to bring the country together.” Still, not all senators are on board, Despite the momentum, action ground to a halt over the weekend when Sen. Bill Hagerty, a Tennessee Republican allied with Trump, refused to speed up the process. Other Republican senators objected to the size, scope, and financing of the package, particularly concerned after the Congressional Budget Office said it would add $256 billion to deficits over the decade. Two Republicans, Sens. Jerry Moran of Kansas and Todd Young of Indiana, had been part of initial negotiations shaping the package but ultimately announced they could not support it. Rather than pressure lawmakers, Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky has stayed behind the scenes for much of the bipartisan work. He has cast his own votes repeatedly to allow the bill to progress, calling the bill a compromise. Trump called Hagerty, who had been his ambassador to Japan, on Sunday, and the senator argued for taking more time for debate and amendments, in part because he wants to slow the march toward Biden’s second phase, a $3.5 trillion bill that Republicans fully oppose. The outline for the bigger $3.5 trillion package is on deck next in the Senate — a more liberal undertaking of child care, elder care, and other programs that is much more partisan and expected to draw only Democratic support. That debate is expected to extend into the fall. Unlike Biden’s bigger $3.5 trillion package, which would be paid for by higher tax rates for corporations and the wealthy, the bipartisan package is to be funded by repurposing other money and with other spending cuts and revenue streams. The bill’s backers argue that the budget office’s analysis was unable to take into account certain revenue streams — including from future economic growth. Senators have spent the past week processing nearly two dozen amendments to the 2,700-page package, but so far, none has substantially changed its framework. One remaining issue, over tax compliance for cryptocurrency brokers, appeared close to being resolved after senators announced they had worked with the Treasury Department to clarify the intent. But an effort to quickly adopt the cryptocurrency compromise was derailed by senators who wanted their own amendments, including one to add $50 billion for shipbuilding and other defense infrastructure. It’s unclear if any further amendments will be adopted. The House is expected to consider both Biden infrastructure packages when it returns from recess in September. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has said the two bills will be considered together, but on Monday, a bipartisan group of centrist lawmakers urged her to bring their smaller plan forward quickly, raising concerns about the bigger bill, in a sign of the complicated politics ahead. “This once-in-a-century investment deserves its own consideration,” wrote Reps. Josh Gottheimer, D-N.J., Jared Golden, D-Maine, and others in a letter obtained by The Associated Press. “We cannot afford unnecessary delays.” Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

‘We have a deal’: Joe Biden announces infrastructure agreement

President Joe Biden announced on Thursday a hard-earned bipartisan agreement on a pared-down infrastructure plan that would make a start on his top legislative priority and validate his efforts to reach across the political aisle. He openly acknowledged that Democrats will likely have to tackle much of the rest on their own. The bill’s price tag at $973 billion over five years, or $1.2 trillion over eight years, is a scaled-back but still significant piece of Biden’s broader proposals. It includes more than a half-trillion dollars in new spending and could open the door to the president’s more sweeping $4 trillion proposals later on. “When we can find common ground, working across party lines, that is what I will seek to do,” said Biden, who deemed the deal “a true bipartisan effort, breaking the ice that too often has kept us frozen in place.” The president stressed that “neither side got everything they wanted in this deal; that’s what it means to compromise” and said that other White House priorities would be tackled separately in a congressional budget process known as reconciliation. He made clear that the two items would be done “in tandem” and that he would not sign the bipartisan deal without the other, bigger piece. Progressive members of Congress declared they would hold to the same approach. “This reminds me of the days when we used to get an awful lot done up in the United States Congress,” said Biden, a former Delaware senator, putting his hand on the shoulder of a stoic-looking Republican Sen. Rob Portman as the president made a surprise appearance with a bipartisan group of senators to announce the deal outside the White House. The deal was struck after months of partisan rancor that has consumed Washington while Biden has insisted that something could be done despite skepticism from many in his own party. Led by Republican Portman of Ohio and Democrat Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, the group included some of the more independent lawmakers in the Senate, some known for bucking their parties. “You know there are many who say bipartisanship is dead in Washington,” said Sinema, “We can use bipartisanship to solve these challenges.” And Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, said, “It sends an important message to the world as well that America can function, can get things done.” The proposal includes both new and existing spending and highlights the struggle lawmakers faced in coming up with ways to pay for it. The investments include $109 billion on roads and highways, $15 billion on electric vehicle infrastructure and transit systems, and $65 billion toward broadband, among other expenditures on airports, drinking water systems, and resiliency efforts to tackle climate change. Rather than Biden’s proposed corporate tax hike that Republicans oppose or the gas tax increase that the president rejected, funds will be tapped from a range of sources — without a full tally yet, according to the White House document. Money will come from COVID-19 relief funds approved in 2020 but not yet spent, as well as untapped unemployment insurance funds that Democrats have been hesitant to poach. Other revenue is expected by going harder after tax cheats by beefing up Internal Revenue Service enforcement. The rest is a hodge-podge of asset sales and accounting tools, including funds coming from 5G telecommunication spectrum lease sales, strategic petroleum reserve, and an expectation that the sweeping investment will generate economic growth — what the White House calls the “macroeconomic impact of infrastructure investment.” The senators from both parties stressed that the deal will create jobs for the economy, a belief that clearly transcended the partisan interests and created a framework for the deal. “We’re going to keep working together–we’re not finished,” Sen. Mitt Romney said. “But America works, the Senate works.” For Biden, the deal was a welcome result. Though for far less than the approximately $2 trillion he originally sought, which is raising some ire on the left, Biden had bet his political capital that he could work with Republicans and showcase that “that American democracy can deliver” and be a counter-example to rising autocracies across the globe. Moreover, Biden and his aides believed that they needed a bipartisan deal on infrastructure to create a permission structure for more moderate Democrats — including Sinema and Joe Manchin of West Virginia — to then be willing to go for a party-line vote for the rest of the president’s agenda. There is still some skepticism on the left. Sen. Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut said the bipartisan agreement is “way too small –paltry, pathetic. I need a clear, ironclad assurance that there will be a really adequate robust package” that will follow the bipartisan agreement. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, like Biden, warned that it must be paired with the president’s bigger goals now being prepared by Congress under a process that could push them through the Senate with only Democratic votes. “There ain’t going to be a bipartisan bill without a reconciliation bill,” Pelosi said. Portman had met privately ahead of the White House meeting with Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell at the Capitol and said afterward that the Kentucky senator “remains open-minded and he’s listening still.” The announcement leaves unclear the fate of Biden’s promises of massive investment to slow climate change, which Biden this spring called “the existential crisis of our times.” Biden’s presidential campaign had helped win progressive backing with pledges of major spending on electric vehicles, charging stations, and research and funding for overhauling the U.S. economy to run on less oil, gas, and coal. The administration is expected to push for some of that in future legislation. But Sen. Bill Cassidy, R-La, stressed that there are billions of dollars for resiliency against extreme weather and the impacts of climate change and deemed Thursday’s deal a “beginning investment.” Biden has sought $1.7 trillion in his American Jobs Plan, part of nearly $4 trillion in broad infrastructure spending on roads, bridges, and broadband internet but also including the so-called care economy of child care centers,

Bipartisan senators reach tentative plan on infrastructure

A bipartisan group of senators reached a tentative framework on an infrastructure deal Wednesday ahead of a crucial meeting with President Joe Biden at the White House. That’s according to a person familiar with the negotiations who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss the private talks. Biden has invited members from the group of 21 senators to the White House on Thursday. “The group made progress towards an outline of a potential agreement, and the President has invited the group to come to the White House tomorrow to discuss this in person,” White House press secretary Jen Psaki said late Wednesday. Biden’s top aides met with senators for back-to-back meetings on Capitol Hill and later huddled with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer as the president reaches for a signature domestic achievement with his sweeping $4 trillion infrastructure plans. The group had been narrowing on a much smaller but still sizable $1 trillion proposal of road, highway, and other traditional infrastructure projects. They have struggled over how to pay for an estimated $579 billion in new spending. “I would say that we’re very, very close, and we’re going to now do the outreach,” Republican Sen. Rob Portman of Ohio told reporters on Capitol Hill as he left an evening meeting with the other senators and White House team. “We have a good, good, balanced group of pay-fors. That was important to both sides, I will say, in good faith, we tried to get there. We didn’t agree on everything, but we were able to get there,” he said. With Republicans opposed to Biden’s proposed corporate tax rate increase, from 21% to 28%, the group has looked at other ways to raise revenue. Biden rejected their idea to allow gas taxes paid at the pump to rise with inflation, viewing it as a financial burden on American drivers. Biden has sought $1.7 trillion in his American Jobs Plan, part of nearly $4 trillion in broad infrastructure spending on roads, bridges and broadband internet but also the so-called care economy of child care centers, hospitals and eldercare. Psaki said the senior staff to the president had two productive meetings with the bipartisan group at the Capitol. The White House team was huddled late into the evening with the Democratic leaders. “We got our framework. We’re going to the White House,” Sen. Mark Warner, D-Va., told reporters. “We wouldn’t be going to the White House if we didn’t think it has broad-based support.” Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Paid in full? Biden, GOP struggle over infrastructure costs

Congressional negotiators and the White House appear open to striking a roughly $1 trillion deal on infrastructure. But they are struggling with the hard part — how to pay for it. As President Joe Biden jumps back into the talks this week, the question of where the money will come from looms large. And time is running short to solve it. Biden wants to increase taxes for corporations and those households making more than $400,000 a year. Republicans have ruled that out, putting forward alternatives that Democrats find unacceptable. Both sides have said the infrastructure spending should be paid for and not add to the national debt. It’s a long-standing challenge with no easy solution, one that puts the bipartisan agreement around infrastructure in tension with the nettlesome realities of governing. It’s a problem that has thwarted previous attempts at an infrastructure bill, including during the Trump administration, and their ability to solve it now is likely to determine whether a bipartisan accord is possible. Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell has said user fees are the way to go. But the White House and key Democratic lawmakers oppose increasing the user fee that has traditionally funded road and bridge construction, the federal gas tax, even if the increase is just allowing it to rise at the rate of inflation from its current level of 18.4 cents per gallon. The federal gas tax has not increased since 1993. “The president’s pledge was not to raise taxes on Americans making less than $400,000 a year, and the proposed gas tax or vehicle mileage tax would do exactly that,” said White House press secretary Jen Psaki. “So that is a nonstarter for him. I’d also note for the mathematicians in the room that only raises $40 billion, which is a fraction of what this proposal would cost.” Biden hosted two key Democratic senators, Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, at the White House on Monday. He told them he was encouraged by the plans that were taking shape but still had questions about the policy and the financing for the proposal, a White House official said. Biden also said he was focused on budget resolution discussions. The two senators were among a group huddling late Monday at the Capitol, some emerging upbeat that a bipartisan deal was within reach. “Significant progress,” said Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine. Sen. Jon Tester, D-Mont., said they were “very close” to having a full proposal from the bipartisan group as soon as Tuesday. One idea under consideration is reallocating money already approved as part of COVID-19 relief measures. Sen. Rob Portman, R-Ohio, said Sunday that they’re looking at repurposing more than $100 billion from COVID-19 relief to help pay for infrastructure. He put the onus on the White House to put forward other ideas since Democrats are balking at indexing the gas tax to inflation or creating a user fee for electric vehicles. “The administration, therefore, will need to come forward with some other ideas without raising taxes,” Portman said on NBC’s “Meet the Press.” “What we don’t want to do is hurt the economy right now as we’re coming out of this pandemic by raising taxes on working families.” With the gas tax likely out, other ideas include raising revenue from communication spectrum leases, and both parties are eyeing funds that could be raised by going after tax dodgers. The Republicans estimate about $63 billion could be raised by beefing up enforcement by the Internal Revenue Service. Democrats say the amount could be even higher. Another complication in the negotiations is that many Democrats question whether the size and scope of the infrastructure package being discussed by the White House and senators is adequate. Within the $1 trillion package, about $579 billion would be new spending, and the remainder would be a continuation of existing programs. Many Democrats are wary of a repeat of 2009 when Barack Obama was president, and they spent months negotiating the details of the Affordable Care Act with Republicans. Eventually, Democrats passed the package that became known as “Obamacare” on their own. “The amount of money that they are proposing is about one-quarter of what the president talked about in terms of new money. That’s not adequate,” said Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., on CNN’s “State of the Union.” Lawmakers are also hoping to influence more than the price tag of the infrastructure bill. One senator key to the talks, Manchin, unveiled his own draft proposal Monday for green energy infrastructure investments. The 423-page bill contains a wish list of energy-related proposals, and he’ll hold a hearing on the plan Thursday in the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., has described the infrastructure bill being negotiated as a good start. But he says most Democrats don’t believe it does enough on climate and also want it to address priorities like paid family leave. He is pushing a “two-track” approach that leaves open the possibility of a far larger bill without Republican votes. Using a special budget, the second infrastructure bill would only take a simple majority of 51 votes to pass. Such a measure could include more of the priorities laid out by Biden as part of his $1.8 trillion American Families Plan, such as paid family leave and universal pre-K for 3- and 4-year-olds. Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., warned the administration not to go that route. “I would just say to President Biden, you’ve got a party that’s divided. You’ve got a Republican Party that’s willing to meet you in the middle for a trillion dollars of infrastructure that could fundamentally change the way America does business in roads, ports, and bridges and accelerate electrical vehicles,” Graham said on “Fox News Sunday.” “You’ve got to decide what kind of president you are and what kind of presidency you want.” Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Joe Biden meets Republicans on virus aid, but no quick deal

President Joe Biden told Republican senators during a two-hour meeting Monday night he’s unwilling to settle on an insufficient coronavirus aid package after they pitched their slimmed-down $618 billion proposal that’s a fraction of the $1.9 trillion he is seeking. No compromise was reached in the lengthy session, Biden’s first with lawmakers at the White House, and Democrats in Congress pushed ahead with groundwork for approving his COVID relief plan with or without Republican votes. Despite the Republican group’s push for bipartisanship, appealing to Biden’s efforts to unify the country, the president made it clear he won’t delay aid in hopes of winning GOP support. White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said that while there were areas of agreement, “the president also reiterated his view that Congress must respond boldly and urgently, and noted many areas which the Republican senators’ proposal does not address.” She said, “He will not slow down work on this urgent crisis response, and will not settle for a package that fails to meet the moment.” The two sides are far apart, with the Republican group of 10 senators focused primarily on the health care crisis and smaller $1,000 direct aid to Americans, and Biden leading Democrats toward a more sweeping rescue package, three times the size, to shore up households, local governments, and a partly shuttered economy. On a fast track, the goal is to have COVID relief approved by March, when extra unemployment assistance and other pandemic aid expires, testing the ability of the new administration and Congress to deliver, with political risks for all sides from failure. Republican Sen. Susan Collins of Maine called the meeting a “frank and very useful” conversation, noting that the president also filled in some details on his proposal. “All of us are concerned about struggling families, teetering small businesses, and an overwhelmed health care system,” said Collins, flanked by other senators outside the White House. Republicans are tapping into bipartisan urgency to improve the nation’s vaccine distribution and vastly expand virus testing with $160 billion in aid. That is similar to what Biden has proposed. But from there, the two plans drastically diverge. The GOP’s $1,000 direct payments would go to fewer households than the $1,400 Biden has proposed, and the Republicans offer only a fraction of what he wants to reopen schools. They also would give nothing to states, money that Democrats argue is just as important, with $350 billion in Biden’s plan to keep police, fire, and other workers on the job. Gone are Democratic priorities such as a gradual lifting of the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour. Wary Democrats pushed ahead at the Capitol, unwilling to take too much time in courting GOP support that may not materialize or in delivering too meager a package that they believe doesn’t address the scope of the nation’s health crisis and economic problems. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer warned that history is filled with “the costs of small thinking.” House and Senate Democrats released a separate budget resolution Monday a step toward approving Biden’s package with a “budget reconciliation” process that wouldn’t depend on Republican support for passage. “The cost of inaction is high and growing, and the time for decisive action is now,” Schumer and Speaker Nancy Pelosi said in a statement. The accelerating talks came as the Congressional Budget Office delivered mixed economic forecasts Monday with robust growth expected at a 4.5% annual rate but employment rates not to return to pre-pandemic levels for several years. The overture from the coalition of 10 GOP senators, mostly centrists, was an attempt to show that at least some in the Republican ranks want to work with Biden’s new administration, rather than simply operating as the opposition in the minority in Congress. But in echoes of the 2009 financial crisis, Democrats warn against too small a package as they believe happened during the Obama administration’s attempt to pull the nation toward recovery. Psaki said earlier Monday there is “obviously a big gap” between the $1.9 trillion package Biden has proposed and the $618 billion counteroffer. An invitation to the GOP senators to meet with Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris at the White House came hours after the lawmakers sent Biden a letter on Sunday urging him to negotiate rather than try to ram through his relief package solely on Democratic votes. “We share many of your priorities,” the senators wrote releasing their plan. The cornerstone of the GOP plan is $160 billion for the health care response — vaccine distribution, a “massive expansion” of testing, protective gear, and funds for rural hospitals, according to a draft. It includes $20 billion to reopen schools compared to $170 billion in Biden’s plan. The Republicans offer $40 billion for Paycheck Protection Program business aid. Under the GOP proposal, $1,000 direct payments would go to individuals earning up to $40,000 a year, or $80,000 for couples. The proposal would begin to phase out the benefit after that, with no payments for individuals earning more than $50,000, or $100,000 for couples. That’s less than Biden’s proposal of $1,400 direct payments at higher income levels, up to $300,000 for some households. The meeting, though private, was Biden’s most public involvement in the negotiations. Winning the support of 10 Republicans would be significant for Biden, potentially giving him the votes needed in the 50-50 Senate where Harris is the tie-breaker. The more liberal wing of his party wants to push the relief package through the budget reconciliation process, which would allow the bill to pass with a 51-vote majority in the Senate, rather than the 60 votes typically needed to advance. The White House remains committed to exploring avenues for bipartisanship even as it prepares for Democrats to move alone on a COVID relief bill, according to a senior administration official granted anonymity to discuss the private thinking. At the same time, the White House may be willing to adjust its ask, perhaps shifting some less virus-oriented aspects into a package that is set to go next before Congress, the