Mark McKinnon says The Circus will evolve when presidential race becomes two-person contest

Mark McKinnon is a man of many hats. Cowboy hats, that is, which is his signature look. He’s done a lot of things in his life, but he’ll probably always be best known for his association as an ad man for George W. Bush‘s presidential campaigns. He’s also the co-creator, co-executive producer and co-host of “The Circus,” a weekly Showtime documentary series on the presidential campaign. The show is a co-production between Showtime and Bloomberg Politics. FloridaPolitics.com spoke with McKinnon last week from Columbus, Ohio, on Super Tuesday III. We mentioned to him how we’ve seen him twice on the campaign trail this year – A week earlier at the Tampa Convention Center for a Marco Rubio rally, and in Derry, New Hampshire when Barbara Bush came out in a much-publicized announcement for a campaign appearance with son Jeb. Florida Politics: You’ve been constantly covering the campaign for The Circus since mid-January. Do you ever get home these days? Mark McKinnon: I get home about one day every couple of weeks. This has been such a circus, and a fascinating one. We got really lucky picking this election to do this, but there’s been no absence of drama. So yeah, I’ve been kicking around in New Hampshire like you were, in Florida where you are, in Columbus today. Sometimes I don’t know until 11 p.m. at night where I’m going to be, which was the case before last, where I thought I was going to Florida, then I got a call that Romney was going to be with (John) Kasich, so I just flipped my plans at midnight and went to Ohio. FP: How big of a crew do you have to capture so much footage for your show each week, and get it edited each Sunday night? MMK: Well, it’s a massive challenge. When I pitched this to television networks – I could write a whole book about how that works – I had the idea 10 years ago. That’s how long it took to get on. The real challenge, and what scared most television executives, was this notion of doing it weekly. Because they’re used to seeing shows months ahead of time. In this case, Showtime only sees it hours before it airs, and at that point, they can’t change much. But to me, the whole idea behind the concept was to produce a great documentary that shows this fascinating world of a presidential campaign. The public sees maybe 1 percent of what really goes on the news. So there’s all this other stuff that happens which is really interesting and entertaining and informative, so I thought it’d be fascinating and dramatic for viewers to see this and see sort of human side of politics and what these people go through. Also importantly, I thought it needed to be in real time as much as possible. So that people were not only seeing an interesting world, but seeing it as it was unfolding, so that it was topical and they feel like they were kind of up on what’s happening. I thought the political junkies would love it — which they do — but people who are casually interested in politics would love it as well because of the way in which every Sunday night they can tune in and in a way that’s much more interesting than a Sunday talk show or reading the newspaper, they can get up to speed on what’s happening. We have 60 people working on this and four crews spanning out across the country, and we have to make a full-blown documentary every week and then wake up every Monday morning, and make another one. So, the production challenge, I mean, it’s a crushing schedule. The logistics of managing of the schedules and moving these crews around is incredible, but Showtime gave us the best in the business, and we’re really excited to be doing it. FP: One of the most interesting scenes to date in the show is one I viewed online dealing with the Trump phenomenon and the general freaking out by the Republican Party establishment. You showed this private lunch in D.C. with of GOP establishment figures, lamenting the rise of Trump and discussing, what if anything can be done about it (Those six men were Ron Hohlt, Vin Weber, Ron Kaufman, Ed Rogers, Ed Goeas and Mike Duncan). MMK: That scene has been one of the most provocative of the season, and it’s gotten a huge response. The idea was that we would find what’s left of the establishment and take them to lunch, and it turns out that there’s six guys left who are the establishment, and we found them, and they’re right out of central casting: They couldn’t be less diverse (laughs). It’s just a bunch of old white guys who have been around Washington forever, and they’re super smart, and they’ve been in every presidential campaign as far back as you can remember, and they’re movers and shakers, and they’re the go-to guys. If you randomly picked 100 people and said who were the six most influential guys, they’d picked these six guys. But the fascinating thing was they agreed to join us at a classic Washington restaurant with black leather and chrome and martinis, but they just opened up and they were completely candid, which you feel sort like you dropped in on a Mafia Boss meeting. But what was surprising about it was A) how candid they are in the situation they find themselves in, but B) that they were very clear that they don’t have a clue about what to do. They have no clear idea or consensus how to approach it. In fact, all six at the table basically had six different ideas on what to do. FP: Your show began in January, when there was so much interest heading into Iowa. We’ll see how soon this race turns into a one-on-one race between the Democratic and Republican nominee. Right now there’s still so much to cover, but do you have any concerns when it slows down to two people and one race. Will the show be able to

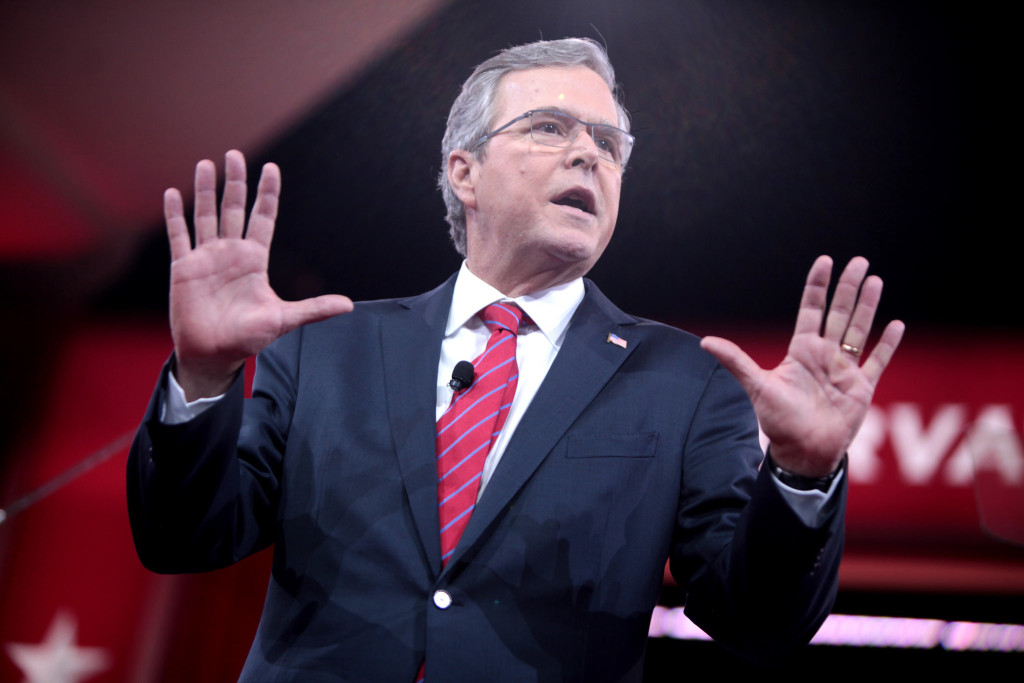

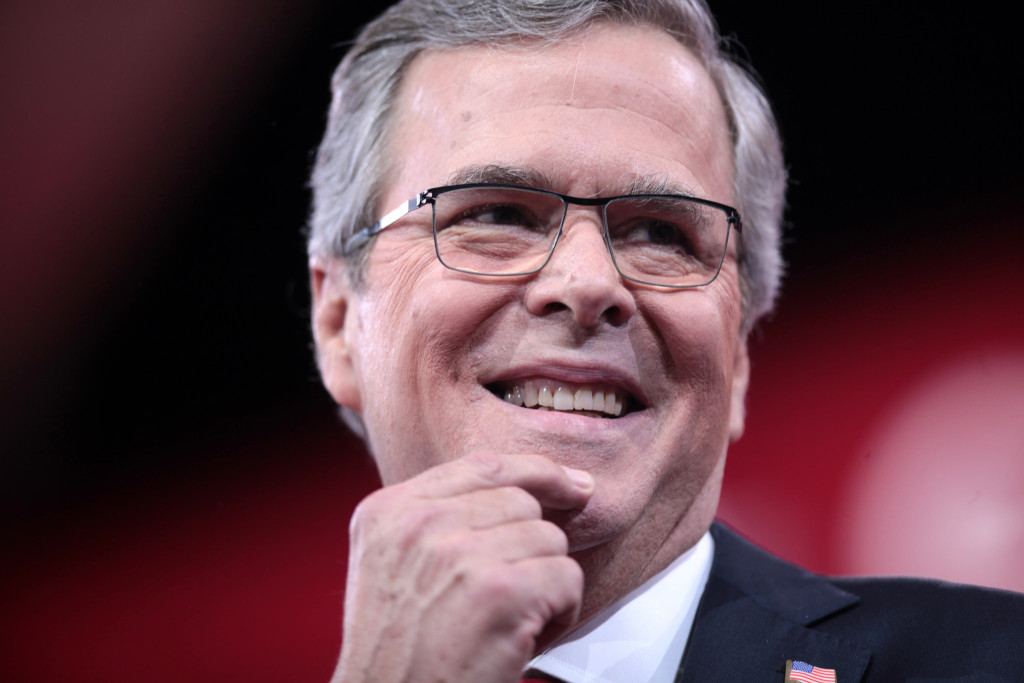

Jeb Bush’s tough week exposes challenges for his likely 2016 bid

Jeb Bush worked his way through the dim hallway of an Arizona resort for hours, shuttling from room to room and meeting with dozens of Republican officials, many for the first time. He was in need of a political reset. For days, he had offered confusing answers to questions about the war in Iraq. He had disappointed Republicans in Iowa, the leadoff state in the nomination chase. And, for a moment, he had forgotten he wasn’t yet a 2016 presidential candidate. Only weeks earlier, donors willing to give millions to put him in the White House were coming to see him at an opulent Miami Beach hotel. Now it was Bush seeking the private gatherings, on the sidelines of a Republican National Committee meeting. The former Florida governor was trying to recover from what was undeniably his worst week in politics since announcing he was considering a run for the White House. “It’s the one thing you have to learn in a campaign,” said Matt Borges, the Ohio Republican Party chairman, as he emerged from a private session. “How to fall down and get up.” Interviews with dozens of RNC members, Bush donors, early state supporters and strategists show: —concerns with his skills as a campaigner. —unease that his designation as a front-runner has yet to materialize in polls. —worries that while they know the Bush name, they don’t yet know this Bush outside of Florida. “In this cycle, there’s less and less off-Broadway. And for Jeb Bush, there’s no off-Broadway,” said Fergus Cullen, the former chairman of the New Hampshire Republican Party. But none of the Republicans interviewed by The Associated Press said Bush had been irreparably damaged. His name recognition and fundraising operation make him a force in the GOP contest. “But I don’t know anybody who ever said in this cycle there’s an untouchable front-runner,” said Ron Kaufman, a Bush supporter who helped arrange some of the meetings in Arizona. Bush’s tough week began with a Fox News interview that included a question about the Iraq war begun by his brother. When President George W. Bush invaded Iraq in 2003, he cited intelligence that showed the country had weapons of mass destruction. The intelligence later was found to be faulty, and no such weapons were uncovered. Over the course of 72 hours, Jeb Bush said he would have ordered the invasion, based on the intelligence presented at the time; claimed he misunderstood the interviewer’s question; then said he would have done something different but refused to say what that might be. On Thursday, he finally answered the original question. “If we’re all supposed to answer hypothetical questions, knowing what we know now, what would you have done? I would not have engaged. I would not have gone into Iraq,” he said. The episode demonstrates Bush’s determination to chart his own path in a family of presidents and avoid publicly judging the policies his father and brother pursued. “I’m not going to go out of my way to say that my brother did this wrong or my dad did this wrong,” Bush said this past week. “It’s just not going to happen.” Bush’s answers about Iraq prompted a wave of commentary from his likely Republican rivals, each eager to show how they’re different with a not-yet-a-candidate still perceived by many as an early front-runner. “If we don’t learn the lesson in Iraq, you don’t understand the lessons that we should learn also from Libya and Syria,” Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul said in an interview with the AP. Bush’s response also fueled Democrats’ preferred narrative of the former Florida governor: that he’s an apologist for a brother who is viewed favorably by less than a third of Americans six years after leaving office. Arizona Democratic Rep. Ruben Gallego, who fought in Iraq and criticizes the war, said reports that Bush considers his older brother an adviser on Middle East issues “makes me question even more if he has the judgment to be president.” Amid all the talk about Iraq, Bush also slipped up for a moment about his candidacy. He’s not yet formally declared his intention to run for president, and saying he’s still thinking about it keeps Bush on the right side of campaign finance rules. Yet after a town hall-style meeting in Nevada on Wednesday, Bush said, “I’m running for president in 2016,” before quickly catching himself, noting, “if I run.” Kaufman and other Bush supporters concede Bush had a challenging week, comparing his tight knit but still growing political operation to a baseball team in spring training. While Bush has a small number of experienced advisers, his decision to put off his formal entry into the campaign until at least June has left them unable to mobilize quickly and respond to problems. But perhaps more than anything, Bush’s week underscored a quiet concern among some Republicans about a candidate who last ran for office 13 years ago: He’s rusty. “He hasn’t been a candidate for anything for years,” said Tom Rath, a New Hampshire-based Republican who advised former President George W. Bush. By Saturday, Bush was able to joke about the issue, which was missing earlier in the week, a sign of a candidate recovering from a blunder. Told by a voter at a town hall in Iowa he hadn’t slipped up at all in the Fox News interview, Bush fessed up with a line that drew laughs. “I misstepped, for sure. I answered a question that wasn’t asked. That’s just what happened,” Bush said, shrugging. “It was a great answer, by the way. But it wasn’t to the question that was asked.” While Bush’s family name and cadre of wealthy donors fuel the perception he is a front-runner for the nomination, early polling suggests voters in key states aren’t buying into the narrative. But polls this early in a presidential campaign are poor predictors of eventual outcomes, and Bush hopes to regain his stride during a weekend trip to Iowa and stops next week

Jeb Bush preparing to delegate many campaign tasks to super PAC

Jeb Bush is preparing to embark on an experiment in presidential politics: delegating many of the nuts-and-bolts tasks of seeking the White House to a separate political organization that can raise unlimited amounts of campaign cash. The concept, in development for months as the former Florida governor has raised tens of millions of dollars for his Right to Rise super PAC, would endow that organization not just with advertising on Bush’s behalf, but with many of the duties typically conducted by a campaign. Should Bush move ahead as his team intends, it is possible that for the first time a super PAC created to support a single candidate would spend more than the candidate’s campaign itself — at least through the primaries. Some of Bush’s donors believe that to be more than likely. The architects of the plan believe the super PAC’s ability to legally raise unlimited amounts of money outweighs its primary disadvantage, that it cannot legally coordinate its actions with Bush or his would-be campaign staff. “Nothing like this has been done before,” said David Keating, president of the Center for Competitive Politics, which opposes limits on campaign finance donations. “It will take a high level of discipline to do it.” The exact design of the strategy remains fluid as Bush approaches an announcement of his intention to run for the Republican nomination in 2016. But at its center is the idea of placing Right to Rise in charge of the brunt of the biggest expense of electing Bush: television advertising and direct mail. Right to Rise could also break into new areas for a candidate-specific super PAC, such as data gathering, highly individualized online advertising and running phone banks. Also on the table is tasking the super PAC with crucial campaign endgame strategies: the operation to get out the vote and efforts to maximize absentee and early voting on Bush’s behalf. The campaign itself would still handle those things that require Bush’s direct involvement, such as candidate travel. It also would still pay for advertising, conduct polling and collect voter data. But the goal is for the campaign to be a streamlined operation that frees Bush to spend less time than in past campaigns raising money, and as much time as possible meeting voters. Bush’s plans were described to The Associated Press by two Republicans and several Bush donors familiar with the plan, who spoke on condition of anonymity because the former Florida governor has not yet announced his candidacy. “This isn’t the product of some genius thinking,” said a Republican familiar with the strategy. “This is the natural progression of the rules as they are set out by the FEC.” Bush spokeswoman Kristy Campbell said: “Any speculation on how a potential campaign would be structured, if he were to move forward, is premature at this time.” The strategy aims to take maximum advantage of the new world of campaign finance created by a pair of 2010 Supreme Court decisions and counts on the Federal Election Commission to remain a passive regulator with little willingness to confront those pushing the envelope of the law. One reason Bush’s aides are comfortable with the strategy is because Mike Murphy, Bush’s longtime political confidant, would probably run the super PAC once Bush enters the race. Meanwhile, David Kochel, a former top adviser to Mitt Romney‘s campaigns and an ally of Bush senior adviser Sally Bradshaw, would probably be the pick to lead Bush’s official campaign. “Every campaign is going to carefully listen to the lawyers as to what is the best way to allocate their resources and how to maximize them,” said Al Cardenas, former chairman of the American Conservative Union and a Bush adviser. “Nobody wants to relinquish any advantage.” For Bush, the potential benefits are enormous. Campaigns can raise only $2,700 per donor for the primary and $2,700 for the general election. But super PACs are able to raise unlimited cash from individuals, corporations and groups such as labor unions. In theory, that means a small group of wealthy Bush supporters could pay for much of the work of electing him by writing massive checks to the super PAC. Bush would begin a White House bid with confidence that he will have the money behind him to make a deep run into the primaries, even if he should stumble early and spook small-dollar donors, starving his own campaign of the money it needs to carry on. Presidential candidates in recent elections have also spent several hours each day privately courting donors. This approach would not eliminate that burden for Bush, but would reduce it. “The idea of a super PAC doing more … means the candidate has to spend less time raising money and can spend more time campaigning,” said longtime Mitt Romney adviser Ron Kaufman, who supports Bush. The main limitation on super PACs is that they cannot coordinate their activities with a campaign. The risk for Bush is that his super PAC will not have access to the candidate and his senior strategists to make pivotal decisions about how to spend the massive amount of money it will take to win the Republican nomination and, if successful, secure the 270 electoral votes he will need to follow his father and brother into the White House. “The one thing you give away when you do that is control,” Kaufman said. Bush will also be dogged by advocates of campaign finance regulation. The Campaign Legal Center, which supports aggressive regulation of money and politics, has already complained to the FEC that Bush is currently flouting the law by raising money for his super PAC while acting like a candidate for president. Others are on guard, too. “In our view, we are headed for an epic national scandal,” said Fred Wertheimer, president of the pro-regulation group Democracy 21. “We intend to carefully and closely monitor all the candidates and their super PACs, because they will eventually provide numerous examples of violations.” All of the major candidates for president