Archives to return Native American remains, burial objects

The remains of Native American people who once lived in Alabama were dug up a century ago — often by amateur archeologists — and given to the state along with the jewelry, urns, and other objects buried with them. The Alabama Department of Archives and History announced this week that it is beginning the process of returning the remains and funerary objects held in its collections to tribes as required by federal law. The department also announced it had removed the funerary objects from displays where the artifacts had sat for years to be viewed by school groups and other visitors. “The origins of those materials and the way they came into our possession is really quite problematic from today’s perspective, and we very much honor and agreed with Native perspectives on what is and isn’t a proper type of material to show in a museum exhibition,” Steve Murray, the director of the Alabama Department of Archives and History, said Thursday. The funerary objects were “the personal property of someone who was buried and then that burial was later disturbed without permission,” Murray said. The 1990 federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act requires federally funded institutions, such as universities, to return Native American remains and cultural items to lineal descendants, Indian Tribes, and Native Hawaiian organizations. However, the return has been slow to happen. The Associated Press reported last month that 870,000 Native American artifacts — including nearly 110,000 human remains — are still in the possession of colleges, museums, and other institutions across the country, according to data maintained by the National Park Service. The first materials to be returned from the Alabama archives will be 37 sets of human remains and 349 associated funerary objects that were excavated from burials at two sites in Montgomery and Lowndes counties in the early 1900s. The graves were of people who lived in Alabama in the 18th century, although some dated back to the 1600s, Murray said. State archives have a total of 114 sets of remains taken from 22 sites across the state, plus the objects that were buried with those people, Murray said. University of Alabama museums are the largest holder of Native American remains and artifacts in Alabama. Republished with the permission of The Associated Press.

Alabama advances ‘divisive concepts’ bill on race, gender

Alabama lawmakers advanced a bill Thursday that would ban “divisive concepts” in classroom lessons and worker training, including the idea that people should feel guilt because of their race. The bill is part of a conservative effort to limit how race and gender are taught in classrooms and worker training sessions, but that Black lawmakers called an endeavor to whitewash the nation’s history. The Alabama House of Representatives approved the bill on a 65-32 vote that largely fell along party lines. The measure now moves to the Alabama Senate. The bill by Republican Rep. Ed Oliver of Dadeville would prohibit a list of “divisive concepts” from being taught in schools and in diversity training for state entities. The banned concepts would include that the United States is “inherently racist or sexist” and that anyone should be asked to accept “a sense of guilt” or a need to work harder because of their race or gender. “It is to prevent kids from being taught to hate America and hate each other,” Oliver said of his bill. He added that it’s intended to create a “nice, safe environment for kids to learn without distractions that may not be age appropriate.” African American representatives sharply criticized the measure. They said it would limit the honest teaching of history and restrict the conversations that give a deeper understanding of race and history just because those conversations might make white people uncomfortable. “My daughter, who is in the chamber today, how am I to explain to her the leaders of this state decided to take on an issue that is really just about erasing history and controlling what’s taught, and not being taught, in this state because a certain group of people feel bad,” said House Minority Leader Anthony Daniels, who is Black. The list in the bill is similar to a now-repealed executive order that former President Donald Trump issued regarding training for federal employees. Similar language has since popped up in bills in more than a dozen states. The bill bans the concepts from being discussed in K-12 schools and says they can be discussed in college classes in a larger course of academic instruction as long as students aren’t forced “to assent.” Oliver disputed that the bill would interfere with history lessons. Lawmakers added an amendment offered by a Democratic lawmaker saying it would not prohibit the teaching of topics or historical events in a historically accurate context. House Republicans named passage of a classroom ban on critical race theory or other “extremist social doctrines” part of their legislative agenda in the election-year session. The approval came after two hours of debate in which some older Black lawmakers described growing up during segregation, and the state Democratic Party chairman said he sometimes gets complimented at the Statehouse for being “articulate.” Answering questions during the debate, Oliver replied he was not familiar with the Middle Passage, the brutal ocean journey that carried enslaved people from Africa to the Americas. “How can you ever bring a bill such as this and not understand the history of racism in this country,” Rep. Juandalynn Givan, a Democrat from Birmingham said. Oliver said after the vote that he understood about the transatlantic passage. Rep. Chris England, who also serves as chairman of the Alabama Democratic Party, said the proposal would discourage the conversations that advance understanding. “This is the poster child bill for prior restraint on free speech, government telling you what you can and cannot talk about it,” England said. Republicans voted to cut off debate after about two hours. Steve Murray, director of the Alabama Department of Archives and History, said amendments to the bill — including one that removed language about how slavery should be taught — addressed some of the instructional barriers. But he said he remains “deeply concerned about the consequences of the legislation if enacted.” Murray said he is concerned teachers will avoid certain topics for fear of running afoul of the new law. “Educators will either decide to navigate those subjects while risking discipline and termination or simply choose to steer clear of any potentially controversial subjects. It seems highly likely that many teachers, already exhausted by the pandemic and unable to afford the loss of a job, will choose the latter route. And who could blame them?” Murray wrote in an email. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

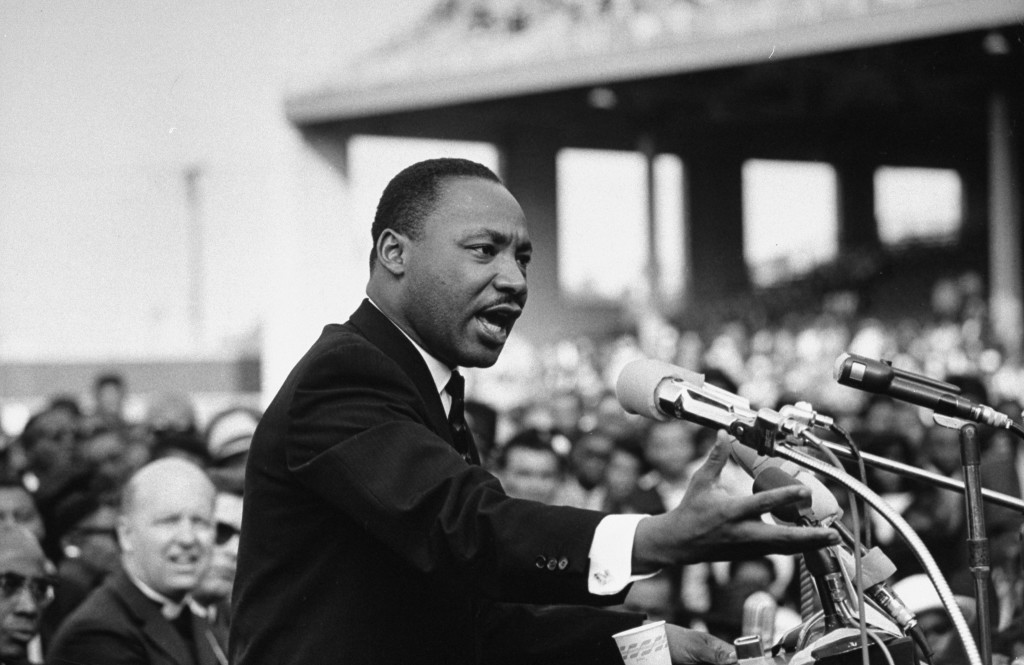

TV station donates thousands of items to Alabama Archives

A television station has donated thousands of items including historic footage from the civil rights era to the Alabama Department of Archives and History, which will make the material available to the public. WSFA-TV in Montgomery announced it had given the agency materials dating to the 1950s, including footage from news conferences by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., coverage of the Freedom Riders in 1961, and original film from the “Stand in the School House Door” by then-Gov. George C. Wallace in 1963. The video also includes scenes from a visit to the NASA center in Huntsville by President John F. Kennedy and Vice President Lyndon Johnson in 1962 and special reports on the death of former University of Alabama football coach Paul “Bear” Bryant in 1983. While the TV station was planning to switch locations, managers determined it wasn’t practical to move the large numbers of delicate film reels and boxes full of video and other items. Steve Murray, the Archives director, said archivists had long suspected the WSFA studios held valuable content for historical preservation, and his department jumped at the opportunity to add to its collection when a phone call came in late 2019. “It was one of those kind of chilling moments … where the hair stands up on the back of your neck when you see these closets after closets of tapes and films,” Murray explained. “Just the opportunity to take something off the shelf and see a label … related to the civil rights movement or to other major public events and Alabama’s life and history really made you, made me appreciate the value of what was there.” The donation includes more than 7,000 audiovisual items in a variety of formats, plus WSFA-TV scrapbooks, photographs, negatives, correspondence with viewers and officials, and newsletters. “We are intimidated by this collection, to be honest with you, because it is huge,” said Meredith McDonough, digital assets director for Archives and History, “and because it is unlike anything we have.” Under the terms of the donation agreement, the department will use the material to benefit state citizens through museum exhibitions, K-12 classrooms, and other educational products. WSFA-TV will be able to broadcast and publish the content of the collection after it is digitized. The agency is processing “test batches” of film and it will take years to fully process the boxes. So far, about 15 hours of film has been digitized, which represents only 30 items in the collection. No payment was made for the collection, WSFA-TV reported. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Voting rights pioneers honored at Alabama state archives

Two pioneers for voting rights have become the first women represented in the Statuary Hall of notable Alabamians at the Alabama Department of Archives and History. The bronze bust likenesses of Amelia Boynton Robinson, a civil rights pioneer, and Pattie Ruffner Jacobs, the state’s leading suffrage activist in the early twentieth century, were unveiled Monday. Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey said the two trailblazers worked to bring about “real and lasting change both in Alabama and in the nation. “The first two women added to the Statuary Hall are both known for lifelong efforts to extend the right to vote to all Alabamians,” Ivey said at the unveiling ceremony. The statues are located at one of the entrances to the state archives and are passed by visitors, researchers and hundreds of students on field trips each year. A longtime civil rights activist, Boynton Robinson is perhaps best known as a leader in the movement in Selma. She was among those beaten during the march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma in March 1965 that became known as “Bloody Sunday.” State troopers teargassed and clubbed marchers. A newspaper photo featuring an unconscious Boynton Robinson drew wide attention to the movement. When the Voting Rights Act was signed into law on Aug. 6, 1965, President Lyndon Johnson invited Robinson to attend the signing as a guest of honor. Boynton Robinson’s granddaughter said it was fulfilling to see her grandmother’s legacy honored. But Carver Boyington said she also hopes visitors remember her grandmothers’ urging to young people to “get off my shoulders” and carry on the work. “What she means by that is she wants us all to move forward in our own activism,” she said. Ruffner was the founder of the Alabama Equal Suffrage Association and a board member for Susan B. Anthony’s National American Woman Suffrage Association. “These additions to our statuary collection represent a step forward in the Archives’ commitment to deliver an inclusive presentation of Alabama’s history,” said Department of Archives and History Director Steve Murray in a press release. “Moreover, the women they honor serve as wonderful models of traits we hope to see embodied by our young people — persistence, courage, and a commitment to justice under the law.” The new works of art were sculpted by Alabama artist Clydetta Fulmer and cast at the Fairhope Foundry.

Department of Archives and History admits perpetuating systemic racism

The agency issued a “statement of recommitment.”