Alabama could lose House seat based on Census response

Alabama is in danger of losing at least one congressional seat based on its current response rate to the U.S. Census, officials said Tuesday. Kay Ivey, during a progress report on the state’s standing with the national head count, said the state’s current participation rate is 59.8%, or 2 percentage points behind the national average. While the state’s performance is better than that of some Southern neighbors, state Census leader Kenneth Boswell said Alabama would lose one of its seven U.S. House seats and possibly two if the counting ended now. Some $13 billion in annual federal funding for programs including school nutrition, health care, infrastructure, and housing also is at stake with the Census, which occurs every 10 years. With the push to promote the Census being affected by the coronavirus pandemic, the state has hired a publicity firm to help spread the word, Boswell said. Events are being planned including a “statewide day of action,” when employers will be asked to let workers complete the Census while on the job. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Greg Reed: Alabama’s innovative reform to medicaid is paying dividends

One of the toughest, yet least-talked about, challenges facing the U.S. today is how to effectively deliver affordable health care to America’s growing population of senior citizens. The U.S. Census Bureau has predicted that by 2035, the number of adults over the age of 65 will exceed the number of children under the age of 18. The graying of America’s population especially creates a challenge for what, at times, can be a fractured and overly complicated health care delivery system. In Alabama, over 90,000 senior citizens’ health care is funded in part via Medicaid, the federally-mandated insurance program that serves the elderly, the poor, and the disabled. Even though Medicaid is federally-mandated, that definitely does not mean that the federal government covers all of the costs — Alabama’s portion of the costs provided by the general fund was $755 million in Fiscal Year 2019, a figure which eats up 37 percent of all non-education spending by the State of Alabama. Over the past several years, I have worked closely with the past two Governors, other legislative leaders, Medicaid Commissioner Stephanie Azar, and private sector partners to identify new delivery models that will bend the cost curve down for Medicaid, while ensuring Alabama’s senior citizens on Medicaid still receive good medical care. In early 2017, I went to Washington, along with Speaker of the Alabama House of Representatives Mac McCutcheon, Medicaid Commissioner Azar, and other state leaders, to meet with Dr. Tom Price, who then served as President Donald Trump’s Secretary of Health and Human Services. That trip and subsequent phone calls and data presentations paid off: in 2018, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in Washington granted Alabama the opportunity to pursue a new delivery model of health care services for the more than 20,000 senior citizens in Alabama who are receiving long-term care through Medicaid. Let me tell you: it is not an easy thing to persuade a federal agency to grant a state a waiver from any program’s requirements. Federal government employees – even the hardest-working and best-intentioned – are not necessarily keen on innovation. In October of 2018, Alabama launched the Integrated Care Network (ICN). In this new model, Medicaid contracts with an Alabama-based healthcare provider to serve the 22,500 patients who are receiving long-term care through Medicaid. These senior patients and their families have expanded choices through the ICN: most are in nursing homes, but about 30 percent have chosen to receive care in the comfort of their own homes. Where are we nearly a year down the road from the ICN launch? A few weeks ago, I convened a meeting of Medicaid, the Department of Senior Services, nursing home owners, and health care providers. Their reports were encouraging. According to Medicaid’s estimates, the ICN model has already saved the state $4 million — and Medicaid projects the savings to grow over the next few years. In 2039, if trends hold, 42 percent of Alabamians will be 60 years or older. For the senior citizens who will need Medicaid’s assistance, it is imperative that we continue to modernize and innovate in the area of health care, especially for programs like Medicaid that are funded by the taxpayers. Newton’s first law states that an object will remain at rest or in uniform motion along a straight line, unless it is acted upon by an external force — inertia, in a word. That is a concept that often applies to government programs and agencies. In this instance, the innovation of the Integrated Care Network represents the external force that is moving Medicaid to a sounder fiscal footing. Greg Reed is the Alabama Senate Majority Leader, and represents Senate District 5, which is comprised of all or parts of Walker, Winston, Fayette, Tuscaloosa, and Jefferson counties.

Daniel Sutter: Is Alabama a poor state?

By most measures of income, yes, but income does not account for the cost of living. Does a low cost of living offset lower income in Alabama? And is a low cost of living necessarily good? Based on Census data, Alabama currently ranks in the bottom five states for both median household and per capita income. Alabama has been in the bottom ten states on these measures for years. In 2018 Alabama ranked 46th, with less than half the cost of living in Hawaii, the highest cost of living state. Annual of income of $50,000 certainly goes further in Alabama than in Hawaii or New York. When adjusting income for cost of living, Alabama ranks in the thirties among states. Do cost of living measures truly account for differences across states? This is an intriguing question. The measured cost of living overstates and understates the full cost in some ways. Cost of living measures overstate differences in living costs due to substitution. People will buy similar goods when one increases in price relative to the others. Suppose that the price of Coke doubles while the price of Pepsi remains unchanged. Many people consider Coke and Pepsi interchangeable, or what economists call close substitutes, and will just buy Pepsi and be little affected by the price increase. Substitution applies with most goods. Consider housing, one of the biggest factors in cost of living differences. A person might rent a one bedroom apartment if they lived in New York City versus a townhouse if they lived in Montgomery. A price index must measure the prices of the same market basket of goods for an apples-to-apples comparison. Yet price differences lead consumers to substitute. Perhaps the bigger difference between high and low cost states is the difference in availability of goods and services in expensive cities like New York or San Francisco versus Alabama. For instance, a major city has a much wider variety of restaurants, including very expensive ones. Is the cost dining out higher? Yes, but dining involves eating food that is closer to your tastes. Here’s another way of considering this point. The cost of dining at one of America’s finest restaurants if you live in Alabama likely includes airfare. The cost of dining out in Alabama does not reflect prices at many fancy restaurants, giving Alabama a low cost of dining. Availability applies to museums, art galleries, and shopping in addition to restaurants. The cost of living is lower but fails to include certain options at all. Differences in availability do not impact everyone the same however. An Alabamian who does not value fancy restaurants, avant garde art, or $25 cups of coffee will not miss out. Economic statistics cannot control for such differences in tastes. Technology and innovation, specifically the internet, Walmart and Amazon, have increased rural America’s consumption opportunities relative to large cities. Alabamians and New Yorker can both now find their favorite music, books and movies online. Economic theory tells us that real estate prices should reflect all the good and bad things about a place. Anything making a community a more desirable place to live – including nice weather, recreation, and natural beauty in addition to consumption opportunities – increases the demand for housing and thus real estate prices. Things that people dislike lead to lower prices. Because not everyone agrees on the desirability of each item, real estate prices must reflect average or typical preferences. Government land use and zoning policies, however, reduce housing supply and increase prices, so price differences do not reflect desirability exclusively. On average, house prices will be lower in places where fewer people prefer to live. Economists consequently recognize the limited appeal of inexpensive housing in recruiting job candidates. Differences in the availability of goods, services and opportunities offset lower prices for common items. As a result, whether you find Alabama to be a poor state is to some degree a matter of taste. Daniel Sutter is the Charles G. Koch Professor of Economics with the Manuel H. Johnson Center for Political Economy at Troy University and host of Econversations on TrojanVision. The opinions expressed in this column are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of Troy University.

States can fight lawsuit to exclude migrants in census

A federal judge on Monday allowed a coalition of 15 states and several major cities to oppose Alabama’s fight to count only citizens and legal residents in U.S. Census numbers used for apportioning congressional seats. U.S. District Judge R. David Proctor granted the coalition’s motions to intervene as defendants in the lawsuit filed by Alabama against the U.S. Census Bureau and Department of Commerce. The coalition, that includes New York, California, Virginia, the District of Columbia and others, will defend the longstanding practice of counting all U.S. residents. New York Attorney General Letitia James said they are intervening because the lawsuit deserves a “robust defense” and questioned the Trump administration’s commitment to providing it. President Donald Trump had pushed to add a citizenship question to the Census. “We will continue to fight to ensure that every person residing in this country is counted — just as the framers intended. Despite the Trump Administration’s attempts to tip the balance of power in the nation and Alabama’s endeavor to continue down that path, we will never stop fighting for a full and accurate count,” James said in a Friday statement after the judge first indicated he would let the states and cities join the suit. Mike Lewis, a spokesman for Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall said the state opposed letting the others join the suit “on the grounds that their interests would be adequately represented by the parties who are already in the case and who are opposing Alabama’s position.” Marshall and U.S. Rep. Mo Brooks of Huntsville filed the 2018 lawsuit that says the practice of counting everyone unfairly shifts political power and electoral votes from “states with low numbers of illegal aliens to states with high numbers of illegal aliens.” Alabama has said it is in danger of losing a congressional vote. The U.S. Constitution says there should be “actual enumeration” of the population counting “the whole number of persons in each State.” The intervening states say that language is clear. Alabama argues that was supposed to be limited to people lawfully admitted to the body politic. In 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against two Texas residents who argued their votes were diluted by the practice of using the whole population to draw legislative district lines. “As the Framers of the Constitution and the Fourteenth Amendment comprehended, representatives serve all residents, not just those eligible or registered to vote,” the court ruled. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

States oppose Alabama’s effort exclude migrants in Census

A coalition of 15 states and several major cities is opposing a lawsuit by the state of Alabama that would have the U.S. Census count only U.S. citizens and other legal residents in totals that play a key role in congressional representation and the distribution of federal funding. New York, California, Virginia, other states, the District of Columbia and some other cities have asked to intervene in Alabama’s federal lawsuit against the U.S. Census Bureau. The states and cities want to defend the longstanding practice of counting all U.S. residents regardless of immigration status, and oppose Alabama’s effort to have it declared illegal. Alabama’s 2018 lawsuit continues a battle over immigration status and the U.S. Census after President Donald Trump abandoned an effort to include a citizenship question on the 2020 Census. New York Attorney General Letitia James said in a statement that the coalition will fight to ensure all people are counted in the census “despite the Trump Administration’s previous racist and xenophobic attempts to tip the balance of power in the nation and Alabama’s endeavor to continue down that path.” “No individual ceases to be a person because they lack documentation. The United States Constitution is crystal clear that every person residing in this country at the time of the decennial census — regardless of legal status — must be counted, and no matter what President Trump says, or Alabama does, that fact will never change,” James said. The cities and states argued in a Monday court filing that the Constitution requires an actual enumeration of the population, which means all people regardless of their citizenship or legal status. Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall and U.S. Rep. Mo Brooks of Huntsville filed the 2018 lawsuit that says counting all residents, regardless of immigration status, was not intended by the Constitution’s writers and the practice unfairly shifts political power and electoral votes from “states with low numbers of illegal aliens to states with high numbers of illegal aliens.” Alabama argued in the lawsuit that “illegal aliens have not been admitted to the political community and thus are not entitled to representation in Congress or the Electoral College.” Alabama has said it could lose a congressional seat as a result of the 2020 Census.Attorneys for the intervening states argued they too have a “significant stake in the outcome of this litigation” because it will affect their political representation in Congress and their eligibility for federal funds. In 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court in a similar case ruled against two Texas residents who argued their votes were diluted by the practice of using the “whole population” to draw legislative district lines. The Department of Justice is defending the Census Bureau in the lawsuit. However, the cities and states seeking to intervene in the case questioned the Trump’s administration commitment to defending the practice. U.S. District Judge David Proctor in December allowed others to intervene in the case, noting the federal government’s “rather halfhearted” argument to dismiss the lawsuit. The latest motion to intervene noted that Trump Attorney General William Barr had noted the “current dispute over whether illegal aliens can be included for apportionment purposes.”The states seeking to intervene in the lawsuit are: New York, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginia and Washington. The United States Conference of Mayors, the District of Columbia and nine other cities and counties, including Seattle and New York City, are also asking to join the lawsuit. The city of Atlanta also asked to intervene in a separate court filing. This story has been corrected to say the opponents include 15 states and several major cities, not 16 states. Republished with permission from the Associated Press.

Government seeks to dismiss Alabama lawsuit over census

The federal government on Friday asked a judge to dismiss Alabama’s lawsuit seeking to include only citizens and other legal residents in 2020 U.S. census counts. U.S. Department of Commerce made the request in a filing responding to the state’s lawsuit. Alabama and U.S. Rep. Mo Brooks sued the Commerce Department and U.S. Census Bureau last year over the practice of counting all U.S. residents, regardless of their citizenship status. The lawsuit contends that Alabama could lose a congressional seat and an electoral vote to a state with a “larger illegal alien population.” In June refused to dismiss the case on jurisdictional grounds, but made no comment on the merits of the case. Lawyers for the government on Friday renewed their request for the judge to dismiss the lawsuit after filing their response. The Constitution says that apportionment shall be decided after “counting the whole number of persons in each state.” It has been the practice to include all U.S. residents in the census counts, which also determine the number of congressional seats for each state.Alabama is seeking to have the practice declared unconstitutional. In 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against two Texas residents who argued their votes were diluted by the practice of using the “whole population” to draw legislative district lines. Republished with permission of the Associated Press.

Steve Marshall: A republic, if we can keep it: the cost of counting illegal aliens in the U.S. census

People of Alabama, Whether you are a Republican or a Democrat, liberal or conservative, you have a right to have your voice heard in the halls of Congress. The 4.8 million Americans who live in Alabama have the same right to representation as 4.8 million Americans living in Southern California or the Texas Panhandle. But that right—the right to equal representation—is quietly under attack. You see, following the 2020 census, Alabama is likely going to lose one of our seven seats in Congress. That is because Alabama has a relatively low number of illegal aliens residing here. Today, as you may be aware, it is estimated that there are at least twelve million individuals currently living in America illegally—a figure almost certainly far lower than the real number, given that it is based on self-reporting—yet it is believed that half of those individuals live in just three states. When the census forms are mailed out to homes across the country, many of those 12 million people will be counted for the purposes of determining the number of congressional districts and electoral votes that each state will be given. This means that states like California and Texas, with large illegal populations, will be given additional seats in Congress and additional votes in the Electoral College. Whatever your political leanings, ponder for a moment what this means. There is absolutely no credible argument to be made that the Constitution allows illegal aliens to vote in U.S. elections. At an even more basic level, now as a resident of Montgomery County, I can no longer vote in a local election in Marshall County, despite my frequent visits there with friends and family. Why is that so? Because our country was founded as a representative democracy. “We the people,” who control our government, control it by way of elections. When you vote in an election, you must prove that you are who you say you are, and that you live where you say you live—that is appropriate because you are choosing who will represent you and your neighbors in Washington or in Montgomery. If we accept that individuals who are in our country illegally do not enjoy the right to vote in our elections—and there is no sound legal argument that they do—then it must follow that these individuals cannot possibly be entitled to the same level of representation in government as American citizens. Otherwise, citizens of states that have more illegal aliens residing there at the time of the census are given disproportionate representation in Congress and in the Electoral College—an irrational proposition. In a state in which a large share of the population cannot vote, those who can vote count more than those who live in states where a larger share of the population is made up of American citizens. Counting large illegal-alien populations in the census unfairly takes voting power—the weight of one vote—away from American citizens based on the presence of citizens of other nations. This cannot be reconciled with the principle of equal representation enshrined in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. Last year, my office filed suit against several federal agencies—including the U.S. Census Bureau—in an effort to guard against our looming loss of representation due to our low illegal-alien population. Recently, we succeeded against an attempt by the federal government to have the suit dismissed. Still, we have many more battles ahead. And we will fight them all, up to the hilt, because our cause is just. We will defend the right of the people of Alabama to equal representation. Steve Marshall, Alabama Attorney General

Redistricting reforms already taking root in many states

While ruling that it had no authority to resolve partisan gerrymandering claims, the U.S. Supreme Court noted Thursday that states could act on their own to try to limit the role of politics in drawing congressional and state legislative districts. Several states already have done so, including some where voters adopted constitutional amendments last year. In most places, state lawmakers and governors are responsible for drawing and approving political district maps following each U.S. Census. But a growing number of states have shifted the task to independent or bipartisan commissions or have changed their redistricting criteria to reduce the likelihood of partisan gerrymandering. Here are some of the states using commissions or other nontraditional methods for the next round of redistricting, which will take place after the 2020 Census. ALASKA: A five-member commission draws districts for the state House and Senate under a 1998 amendment to the state constitution. Two members are appointed by the governor and one each by the presiding officers of the House and Senate and the chief justice of the Supreme Court. Districts must be compact, contiguous and contain “a relatively integrated socio-economic area.” Alaska has only one congressional district. ARIZONA: Congressional and state legislative districts are drawn by a five-member commission established under a ballot measure approved by voters in 2000. Twenty-five potential redistricting commissioners are nominated by the same state panel that handles appeals court nominees. The Legislature’s two Republican leaders choose two commissioners from 10 Republican candidates, and the two Democratic leaders chose two from their party’s 10 nominees. Those four commissioners then select the fifth member, who must be an independent and serves as panel chairman. The constitution says “competitive districts” should be drawn as long as that doesn’t detract from the goals of having compact, contiguous districts that respect communities of interest. Democrats have accused Gov. Doug Ducey, a Republican, of influencing the commission’s composition by stacking the appellate court panel that narrows the field of potential candidates. The panel has eight Republicans and five independents, but no Democrats. CALIFORNIA: Voters approved a pair of ballot measures, in 2008 and 2010, creating a 14-member commission to draw congressional and state legislative districts. A state auditor’s panel takes applications and selects 60 potential redistricting commissioners — 20 Democrats, 20 Republicans and 20 others. The state Assembly and Senate majority and minority leaders each can eliminate two nominees from each political category. Eight redistricting commissioners — three Democrats, three Republicans and two unaffiliated members — are randomly selected from the remaining pool of candidates. Those commissioners then select an additional two Democrats, two Republicans and two unaffiliated members. Approving a map requires nine votes, including three from each political category of members. The constitution says the districts should be compact and keep cities, counties and communities of interest together to the extent possible. COLORADO: Congressional and state legislative districts will be drawn by a 12-member commission, under a pair of constitutional amendments approved by voters last November. The commission will consist of four Republicans, four Democrats and four independents selected from a pool of applicants. Half will be chosen randomly and the rest by a judicial panel. Nonpartisan legislative staff will draft proposed maps for the commission’s approval; maps will require at least eight votes, including two from independents. The state Supreme Court will then review the maps to determine whether legal criteria were followed. The districts must be compact, preserve communities of interest and “maximize the number of politically competitive districts.” HAWAII: Congressional and state legislative districts are drawn by a nine-member commission. The majority and minority party leaders in the House and Senate each appoint two commissioners. Those eight then pick a ninth commissioner. If they can’t agree, the ninth member is appointed by the state Supreme Court. Districts cannot be drawn to “unduly favor a person or political faction.” IDAHO: A six-member commission is responsible for drawing both congressional and state legislative districts. Two-thirds of the commissioners must vote to approve a map. The majority and minority party leaders in each legislative chamber each select one person to serve on the commission; the state chairmen of the Republican and Democratic parties also each select a commissioner. Mapmakers should avoid “oddly shaped” districts and preserve “traditional neighborhoods and local communities of interest.” IOWA: The nonpartisan Legislative Services Agency draws maps for congressional and state legislative districts, which are submitted to the Legislature for approval. Districts must consist of “convenient contiguous territory” and be reasonably compact. Districts cannot be drawn to favor a political party, incumbent or other person or group. MICHIGAN: Under a constitutional amendment approved by voters last November, congressional and state legislative districts will be drawn by a 13-member citizens’ commission. It will consist of four Democrats, four Republicans and five independents randomly selected by the secretary of state from among applicants. Approval of districts will require a majority vote with support of at least two Democrats, two Republicans and two independents. If that fails, each commissioner would submit a plan and rank their options by preference, with the highest-ranked plan prevailing. In case of a tie, the secretary of state would randomly select the final plan. Districts must be compact, contiguous, limit splitting of counties and cities, “reflect the state’s diverse population and communities of interest,” not favor or disfavor incumbents, and not provide a disproportionate advantage to any political party. MISSOURI: A constitutional amendment approved by voters last November will require a new nonpartisan state demographer to draft maps for state House and Senate districts. The demographer is to design districts to achieve “partisan fairness” and “competitiveness” as determined by statistical measurements using the results of previous elections. Districts also shall be contiguous and limit splits among counties and cities. Compact districts are preferred but rank last among the criteria. The maps will be submitted to a pair of existing bipartisan commissions for approval. The governor will appoint a 10-member commission for the Senate districts, choosing five Republicans and five Democrats from among nominees submitted by

The fastest growing and shrinking cities in Alabama

Alabama’s list of largest cities is due for another shakeup. In 2016, Huntsville passed Mobile to become the state’s third-largest city. Next year the Rocket City will likely pass Montgomery to become the second-largest.If population trends hold true over the next few years, it won’t be long until Huntsville stands at the top of the list. The U.S. Census Bureau released new city population estimates Thursday. According to the estimates, Birmingham, the largest city in the state, is losing population. The Magic City’s population has been mostly stagnant – no growth or major loss – since 2010. But for the first time in nearly 100 years, its population is now below 210,000. And Montgomery continues to steadily lose people. The state’s capital started the decade with a healthy 15,000 population lead over Huntsville. Now that lead has dwindled to fewer than 1,000 people. Huntsville, meanwhile, has been adding population at a substantial rate since the start of the decade. In those eight years the city has added more than 17,000 people. If those trends continue at their current pace, Huntsville could pass Birmingham in population in just six years.Huntsville was one of only three Alabama cities to grow its population by 10,000 people or more since 2010. The other two are notably college towns. Auburn added around 12,300 people and Tuscaloosa added around 10,600 people since 2010. Auburn’s growth is impressive. The city is also in the top 10 in terms of percentage growth in the state. Among Alabama cities with at least 10,000 people, only five grew at a faster rate than Auburn. Three of those are in Baldwin County, which continues to grow like a weed. Tuscaloosa’s growth has been a bit slower than Auburn’s, but it remains a significantly larger city. According to the estimates, Tuscaloosa passed the 100,000 population mark in 2017, and had 101,113 people in 2018. Auburn sat at 65,738 people in 2018. Montgomery isn’t the only large city that’s shrinking. Mobile has lost more than 5,000 people since 2010. Birmingham, Anniston and Gadsden have all lost significant population, as have Decatur, Eufaula and Prichard. But perhaps the most alarming population loss has come from Selma, a historic civil rights town that AL.com reported last year was the fastest shrinking city in the state. That’s still true, according to the new estimates. Selma has lost nearly 14 percent of its population since 2010, the worst rate in the state over that span, according to the Census. It’s the only city in the state to lose more than 10 percent of its population over that time. By Ramsey Archibald, Al.com. Republished with permission of the Associated Press.

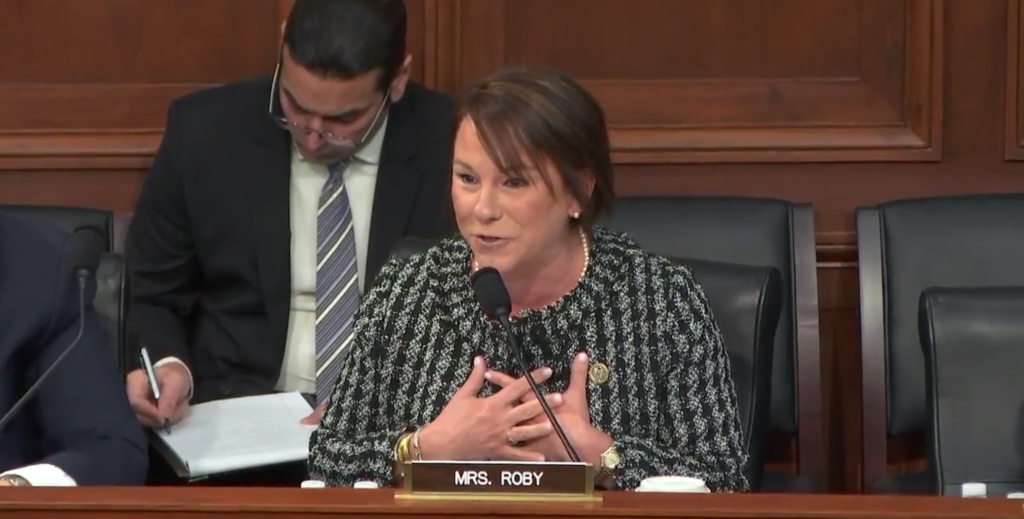

Martha Roby: An accurate 2020 census

Every ten years, the U.S. Census Bureau conducts a count of every resident in the United States, as mandated by Article I, Section 2 of our Constitution. This action is critically important to understanding current facts and figures about our country’s people, places, and economy. It’s hard to believe that a decade has almost passed, and we are just eleven months away from next year’s April 1 Census. It goes without saying that a lot has changed over the last ten years, especially on the technological front. As times and trends change, it is important that the method by which we conduct the Census also evolves to ensure we are reaching the most people possible. That said, it’s no surprise that in 2020, we will largely depend on an Internet system to count Americans, relying heavily on digital advertising and social media platforms to spread the word. As the Census Bureau works to modernize its various platforms ahead of the 2020 Census, I was glad to hear about these efforts directly from Dr. Steven Dillingham, Director of the U.S. Census Bureau, during a recent Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Appropriations Subcommittee hearing. During this hearing, I had the opportunity to discuss with Director Dillingham how important it is that all Alabamians be accurately counted in 2020. Back in 2010, our state did not do a great job accounting for all of our people, especially children below the age of six and those individuals in rural communities. As I told Director Dillingham, we must make sure that is not the case in next year’s count. You see, the Census doesn’t just decide the number of congressional seats Alabama has, it also decides our number of Electoral College votes. We currently have nine Electoral College votes, and if the 2020 Census is not accurate, that number will drop to eight. This is a very big deal, and it is something we Alabamians do not want to see happen. The Census also determines the amount of federal dollars that come into Alabama, specifically to hospitals, job training centers, schools, infrastructure projects, and other emergency services. Inaccurate Census numbers force our state to do more with less, and that cannot happen again in 2020. As we all know, Alabama’s Second District and the rest of the Southeastern corner of the state are made up of very rural communities. To achieve the most accurate count possible in next year’s Census, it is critical that we reach the men, women, and children living in the rural areas throughout the country. During my conversation with Director Dillingham, I asked him how the Census Bureau plans to use its resources to partner with our state and community-based organizations to encourage participation in the Census, especially in hard-to-count, rural communities. I made sure Director Dillingham understands that a large part of our district, and many areas of our state, lack access to reliable broadband and thus may not utilize the Internet and social media enough to encounter online advertising about the upcoming Census. This will certainly be a challenge, but it is one we must address. I also brought up another challenging reality that we must face: Over the last year, Alabama and other states in the Southeast have been beaten with hurricanes, tornadoes, and other powerful storms. There has been flooding throughout the Midwest and fires ravaging California. These disastrous events have caused thousands of Americans to be displaced from their homes, and we must ensure that they, too, are counted in next year’s Census. To make sure the 2020 Census is as accurate as it can possibly be, it is important that leaders on all levels of federal, state, and local governments are communicating about ways we can spread the word and reach the most people. I believe the modernization of our Census process will lead to excellent results next year, but it is critical that we make every effort to reach those who have been displaced by severe weather as well as the people in rural communities who may not have reliable access to social media and online advertising. The future of our state’s representation in Congress and the Electoral College are at stake, and we must ensure that Alabama receives its fair share of federal funding for numerous programs we all depend on. I encourage you to start spreading the word about the April 1, 2020, Census. It will be here before we know it, and Alabama needs an accurate count.# Martha Roby represents Alabama’s Second Congressional District. She lives in Montgomery, Alabama, with her husband Riley and their two children.

Alabama’s population gain lags behind other states

Alabama’s total population gain last year might fill up half of Cramton Bowl, Montgomery’s municipal football stadium. That could spell trouble for the state’s political prospects. The U.S. Census Bureau this week estimated that Alabama grew by about 12,751 people during the year ending July 1, a minimal 0.2 percent increase that was slower than other states. Alabama’s birth rate is roughly comparable to the nation as a whole — during the year, Alabama had 11.7 births per 1,000 people, vs. about 11.8 per 1,000 for the United States. But the state also had the second-highest rate of death in the country last year, reporting 10.9 deaths per 1,000 people vs. 8.6 for the nation, possibly a reflection of an aging population. West Virginia, with 12.4 deaths per 1,000, reported the highest mortality rate. The rate of people moving into the state was also low, due in part to low rates of immigration in Alabama. The Census Bureau estimates Alabama gained 1.9 people per 1,000 from people moving into the state last year. Most of that came from individuals moving from other parts of the country. The rate of international migration was 0.7 individual per 1,000, well below the national rate of 3.0 per 1,000. Alabama’s birth rate was below the South’s overall rate (12.1 per 1,000), as was the rate of migration into the state (6.1 per thousand). The death rate in Alabama was notably higher than the region’s (8.9 per 1,000). The state had 4,887,871 residents on July 1, according to the Census. With reapportionment looming after the 2020 Census, Alabama is on the cusp of losing one of its seven seats in the U.S. House of Representatives, a development that could reduce the state’s voice in the lower chamber. It would be the first loss of a seat for the state since 1970. The state’s growth rate among the states also fell from 27th in 2017 to 34th in 2018, which could possibly increase the chances of the state losing a seat. State officials are trying to prevent the loss in several ways. Gov. Kay Ivey’s administration has launched a program aimed at securing a high participation rate in the Census. Attorney General Steve Marshall has also sued to try to prevent the counting of undocumented immigrants in the Census, a move that could reduce the official level of growth in states like Texas, though it could also reduce the total count of people in Alabama. Nevada had the highest percentage growth last year, with its population going up 2.1 percent, according to Census estimates. Idaho also reported 2.1 percent growth. Texas added the most individuals, with the Census estimating 379,128 joining the residents of the state last year. Florida added 322,513 people last year. West Virginia’s population shrunk 0.6 percent last year, while Illinois saw a population drop of 0.4 percent. Alaska; Connecticut; Hawaii; Louisiana; Mississippi; New York and Wyoming also reported population drops last year. Republished with permission from the Associated Press.

U.S. Census Bureau now hiring workers for 2020 Census in Alabama

Alabama residents looking for some extra income may have a great opportunity to help their country, their state and earn a little extra money all at the same time with a federal job related to the 2020 Census in Alabama. The U.S. Census Bureau is now hiring workers for temporary jobs available in Alabama in advance of the 2020 Census. Those jobs include census takers, recruiting assistants, office staff and supervisory staff out of their Birmingham, Ala. office with pay ranging from $14.50-18 an hour. “The 2020 census is critical to the future of our state, and I’d like to encourage Alabamians – especially retirees, college students or others looking for part-time, temporary work – to take advantage of this opportunity not only to earn a paycheck but assist the Census Bureau with a task that will benefit all of the people of our state,” said Gov. Kay Ivey in a news release. The U.S. Census and Alabama Participation in the census count, which is required every 10 years by the U.S. Constitution, affects many aspects of Alabama, including congressional representation and the amount of federal funding allocated to the state for many critical programs. While the census count is several months away, taking place in April 2020, the state is already gearing up preparations. In August, Ivey issued an executive order establishing the Alabama Counts! 2020 Census Committee to promote and educate the public on census activities. Led by the Alabama Department of Economic and Community Affairs (ADECA), the committee is currently filling in membership of its eight subcommittees and will develop an action plan to guide the state’s efforts at maximum participation in the 2020 census. “The stakes are high for Alabama in the 2020 U.S. Census, and our success depends greatly on our ability to help Alabamians understand the importance of completing and submitting their census forms,” Ivey previously said of the census. “For that reason, I am forming this committee a full 20 months before the April 1, 2020 census count to bring leaders of many statewide public and private groups together to ensure every Alabamian knows the importance of doing their part and participating in the census. When we all do our duty, we ensure that the state gets our fair share of funding for dozens of critical programs and ensure we maintain fair representation in Congress.”