Alabama Supreme Court gives go ahead for execution by nitrogen hypoxia

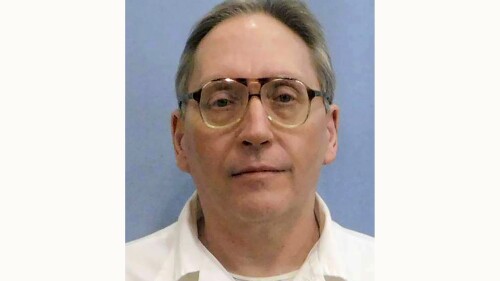

Ralph Chapoco, Alabama Reflector Alabama is one step closer to becoming the first state to execute someone by nitrogen hypoxia. In a 6-2 decision handed down Wednesday, the Alabama Supreme Court allowed the state to proceed with the execution of Kenneth Eugene Smith, convicted of the 1988 murder of Elizabeth Sennett, under that method. Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall said in a statement Wednesday that Sennett’s family had “waited an unconscionable 35 years to see justice served.” “Though the wait has been far too long, I am grateful that our talented capital litigators have nearly gotten this case to the finish line,” the statement said. Chief Justice Tom Parker and Associate Justice Greg Cook dissented but gave no additional comment. Nitrogen hypoxia has never been used on a human being as a means of execution, and professional veterinary associations have discouraged its use in the euthanization of animals. Smith’s attorneys said in a statement Thursday that they were disappointed in the decision and would continue to work through the judicial process. Smith currently has an appeal pending with the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals claiming that attempting to execute him a second time violates his constitutional rights. “It is noteworthy that two justices dissented from this Order,” wrote Robert Grass, an attorney for Smith. “Like the eleven jurors who did not believe Mr. Smith should be executed, we remain hopeful that those who review this case will see that a second attempt to execute Mr. Smith – this time with an experimental, never-before-used method and with a protocol that has never been fully disclosed to him or his counsel – is unwarranted and unjust.” The order gives the Alabama Department of Corrections the authority to carry out Smith’s execution within the time frame set by Gov. Kay Ivey, which cannot happen less than 30 days from Wednesday, when the court published its decision. The Attorney General’s Office filed a motion with the Alabama Supreme Court back in August, requesting the court set a date for Smith’s execution. Smith’s attorneys requested the court reject the state’s motion in September, stating that nitrogen hypoxia has not been tested and only recently released the protocol for using that method of execution. A jury convicted Smith in 1996 in the plot to murder Sennett and voted to sentence him to life without the possibility of parole. The judge in the case overrode the jury recommendation and sentenced Smith to death. Alabama abolished judicial override in 2017, the last state in the country to do so. But the rule was not made retroactive. In May the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a lower court’s decision that allowed him to select his method of execution, in this case is death by nitrogen hypoxia. The high court turned down the appeal by the Alabama Department of Corrections, which argued that Smith was pursuing a delaying tactic. Smith was scheduled to be executed in November following the botched executions of Joe Nathan James Jr. and Alan Miller. However, his execution was called off after ADOC staff repeatedly failed to secure a vein to carry out the execution. Smith’s attorneys wrote in a brief last January that he “continues to experience physical and emotional pain, including lingering pain in his arm, near his collarbone, back spasms, difficulty sleeping, and likely post-traumatic stress disorder” from the failed execution. Death through nitrogen hypoxia became an available method for executing people on death row after the Legislature passed a bill sponsored by Sen. Trip Pittman, R-Montrose, allowing its use. He said that the method was more humane than lethal injection. Doctors and medical ethicists have criticized those claims. “Last year, after Alabama tortured multiple people in botched executions using lethal injection, we encouraged the state to pursue an independent evaluation of its execution protocols,” said Alison Mollman, interim legal director of the ACLU of Alabama. “Governor Ivey and the Alabama Department of Corrections failed to complete an independent review and instead insisted the problem was not having enough time to kill someone. Now, at the urging of Attorney General Steve Marshall, Alabama is rushing to put a man to death with an untested, unproven, and never-before-used method of execution. As Alabama races to experiment on incarcerated people with nitrogen gas, they put the lives of correctional staff, spiritual advisers, the media, and victims at risk by potentially exposing them to an odorless and lethal gas. Using this method has no benefit on public safety. Governor Ivey and Attorney General Marshall have a responsibility to stop the execution of Mr. Smith.” The Death Penalty Information Center, a nonprofit that students and collects data on the death penalty, criticized Alabama’s move toward nitrogen executions in a statement on Thursday. “No state has ever used nitrogen in an execution, and there are still too many unanswered questions for Alabama officials to responsibly move forward with this protocol,” the statement said. “Mr. Smith has already endured one botched execution; he should not now face another attempt that carries this much risk and uncertainty.” Alabama Reflector is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Alabama Reflector maintains editorial independence. Follow Alabama Reflector on Facebook and Twitter.

Alabama to carry out first lethal injection after review of execution procedures

Alabama plans to execute an inmate on Thursday for the 2001 beating death of a woman as the state seeks to carry out its first lethal injection after a pause in executions following a string of problems with inserting the IVs. James Barber, 64, is scheduled to be put to death Thursday evening at a South Alabama prison. It is the first execution scheduled in the state since Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey paused executions in November to conduct an internal review. Ivey ordered the review after two lethal injections were called off because of difficulties inserting IVs into the condemned men’s veins. Attorneys for inmate Alan Miller said prison staff poked him with needles for over an hour as they unsuccessfully tried to connect an IV line to him and, at one point, left him hanging vertically on a gurney during his aborted execution in September. State officials called off the November execution of Kenneth Eugene Smith after they said they were unsuccessful in connecting the second of two required lines. Advocacy groups claimed a third execution, carried out in July after a delay because of IV problems, was botched because of multiple attempts to connect the line, a claim the state has disputed. “Given Alabama’s recent history of botched executions, it is staggering that James Barber’s lethal injection is set to take place,” Maya Foa, director of the anti-death penalty group Reprieve, said. “Three executions in a row went horribly wrong in Alabama last year, yet officials have asserted that ‘no deficiencies’ were found in their execution process.” Barber was convicted in the 2001 beating death of 75-year-old Dorothy Epps in Harvest, Ala. Prosecutors said Barber, a handyman who knew Epps’ daughter, confessed to killing Epps with a claw hammer and fleeing with her purse. Jurors voted 11-1 to recommend a death sentence, which a judge imposed. Barber’s execution was scheduled for the same day that Oklahoma executed Jemaine Cannon for stabbing a Tulsa woman to death with a butcher knife in 1995 after his escape from a prison work center. Attorneys for Barber have asked federal courts to block the lethal injection, citing the state’s past problems. The 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals refused to halt the execution on Wednesday. Judges noted the state had conducted a review of procedures and wrote that “Barber’s claim that the same pattern would continue to occur” is “purely speculative.” The court noted that the Alabama Department of Corrections had changed medical personnel and lengthened the timeframe for executions. “ADOC conducted a full review of its execution processes and procedures, determined that no deficiencies existed with the protocol itself, and instituted certain changes to help ensure successful constitutional executions,” the court wrote. Barber appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday, asking justices to stay the execution. His lawyers wrote that the “fourth lethal injection execution that will likely be botched in the same manner as the prior three.” “Alabama’s past three execution proceedings imposed needless physical and emotional suffering on inmates to such an extent that Alabama paused its lethal injection executions and undertook an internal review of its procedures,” Barber’s lawyers wrote in the Supreme Court filing. “Shockingly, however, that review resulted in no substantive changes to Alabama’s procedures or to the qualifications of those carrying out lethal injection executions.” The Alabama attorney general’s office has urged the Supreme Court to let the execution proceed. The state wrote that the previous executions were called off because of a “confluence of events—including health issues specific to the individual inmates and last-minute litigation brought by the inmates that dramatically shortened the window for ADOC officials to conduct the executions.” “Dorothy Epps, Smith’s victim, has survivors who have already waited overlong to see justice done,” the office added. The state conducted an internal review of procedures. Ivey rebuffed requests from several groups, including a group of faith leaders, to follow the example of Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee and authorize an independent review of the state’s execution procedures. One of the changes Alabama made following the internal review was to give the state more time to carry out the execution. The Alabama Supreme Court did away with its customary midnight deadline to get an execution underway in order to give the state more time to establish an IV line and battle last-minute legal appeals. The state will have until 6 a.m. Friday to start Barber’s execution. Republished with the permission of The Associated Press.

Faith leaders urge independent review of Alabama executions

More than 170 pastors and other faith leaders on Tuesday urged Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey to authorize an independent review of execution procedures, as Oklahoma and Tennessee did after a series of failed lethal injections in those states. The group applauded Ivey for taking the “bold and necessary step” of ordering a review of Alabama execution procedures following problems locating intravenous lines during three lethal injections but said that review should be done by those outside the state prison system. Ivey, in November, ordered the Alabama Department of Corrections, which carries out executions, to undertake the review. “Given the gravity of what has transpired, we respectfully request a comprehensive, independent, and external review of Alabama’s death penalty procedures,” they wrote in a letter delivered to Ivey’s Alabama Capitol Office on Tuesday. The faith leaders said the review should be conducted openly — and by a person or group other than the Alabama Department of Corrections. “The fact of the matter is that an agency that has failed repeatedly to get its own house in order cannot be trusted to privately conduct an investigation into problems it is causing,” they wrote. The group cited the example of Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee, who authorized a state review after acknowledging that the state failed to ensure its lethal injection drugs were properly tested. A former U.S. attorney conducted the review. It found Tennessee had not complied with its own lethal injection process ever since it was revised in 2018, resulting in several executions that were conducted without proper testing of the drugs used. A review was also conducted in Oklahoma after the 2014 execution of Clayton Lockett. After the first drug was administered, Lockett struggled on a gurney for 43 minutes before he was declared dead. The review was conducted by a separate state agency from the prison system. It was later learned that members of the execution team had improperly inserted an IV into a vein in Lockett’s groin. The independent Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission also scrutinized state procedures. Ivey cited concerns for the victims and their families in ordering the review in Alabama. “For the sake of the victims and their families, we’ve got to get this right,” Ivey said. Carrying out an execution is the state’s responsibility to uphold the law and to ensure justice, Ivey spokesperson Gina Maiola wrote in a statement. “This is a responsibility Governor Ivey takes very seriously, and as she has made very clear along the way, this will review remain transparent as is appropriate while also protecting sensitive information,” she continued. The Alabama review has so far yielded changes to make it easier to carry out death sentences. At Ivey’s request, the Alabama Supreme Court gave the state a longer amount of time to carry out executions by allowing death warrants authorizing an execution to last for more than 24 hours. Ivey announced the pause on executions after a third failed lethal injection in the state. The state called off the November execution of Kenneth Eugene Smith after failing to get an intravenous line connected within the 100-minute window between when courts cleared the way for it to begin and the death warrant’s midnight deadline expired. In September, the state called off the scheduled execution of Alan Miller because of difficulty accessing his veins. Alabama, in 2018 called off the execution of Doyle Hamm because of problems getting the intravenous line connected. Hamm had damaged veins because of lymphoma, hepatitis, and past drug use, his lawyer said. The state completed an execution in July, but only after a three-hour delay caused at least partly by the same problem with starting an IV line. Republished with the permission of The Associated Press.

Gov. Kay Ivey seeks more time to carry out executions

Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey on Monday said she wants to give the state additional time to carry out an execution after a series of failed lethal injections. The Republican governor sent a letter to the Alabama Supreme Court asking justices to alter a longstanding rule that limits execution warrants to a single date. It is the first change requested by Ivey after announcing a “top-to-bottom” review of execution procedures. The review is ongoing, Ivey spokeswoman Gina Maiola said Monday. Alabama prison officials called off two recent scheduled lethal injections — for Kenneth Eugene Smith in November and Alan Miller in September — as midnight approached after last-minute legal appeals and difficulties by the execution team in connecting an IV line to each inmate. Under Ivey’s proposal, the state corrections commissioner could immediately designate a new execution date if a last-minute stay or some other delay prevents the state from carrying out an execution on the original date listed on the death warrant. Currently, if the state can’t get the procedure underway by midnight, officials must ask the Alabama Supreme Court to set a new execution date. The governor said other states do not have the strict one-day time frame. “In several recent executions, last-minute gamesmanship by death row inmates and their lawyers has consumed a lot of valuable time, preventing the department from carrying out its execution protocol between the conclusion of all legal challenges in the federal courts and the expiration at the death warrant issued by your court,” Ivey wrote. While Ivey placed the blame on the single-day time frame and last-minute appeals, lawyers for inmates and advocacy groups have said the repeated difficulties with establishing an IV line shows something is wrong with Alabama’s procedures. In a court filing opposing the setting of a new execution date for Smith, his lawyers wrote that his treatment “does not fall within society’s standards for a constitutional execution. The botched execution was terrifying and extremely painful for Mr. Smith.” Ivey last month requested a pause in executions after the state called off Smith’s lethal injection. It was the second time this year and the third time since 2018 that the state was unable to put an inmate to death. The state completed an execution in July, but only after a three-hour delay caused at least partly by trouble starting an IV line on Joe Nathan James Jr. Ivey said the state is also looking at moving up the current 6 p.m. start time for executions to give the Department of Corrections more time. Corrections Commissioner John Hamm will make a recommendation to her for a new time, she told justices. Republished with the permission of The Associated Press.

Alabama fails to complete lethal injection for 3rd time

Alabama’s string of troubled lethal injections, which worsened late Thursday as prison workers aborted another execution because of a problem with intravenous lines, is unprecedented nationally, a group that tracks capital punishment said Friday. The uncompleted execution of Kenneth Eugene Smith was the state’s second such instance of being unable to kill an inmate in the past two months and its third since 2018. The state completed an execution in July, but only after a three-hour delay caused at least partly by the same problem with starting an IV line. A leader at the Death Penalty Information Center, an anti-death penalty group with a large database on executions, said no state other than Alabama has had to halt an execution in progress since 2017, when Ohio halted Alva Campbell’s lethal injection because workers couldn’t find a vein. According to Ngozi Ndulue, deputy director of the Washington-based group, the only other lethal injection stopped before an inmate died also was in Ohio in 2009. “So Alabama has more aborted lethal injections in the past few years than the rest of the country has overall,” she said. Something has obviously gone wrong with the state’s execution procedure, Ndulue said. “I think Alabama clearly has some explaining to do, but also some reflection to do about what is going wrong in its execution process,” she said. “The question is whether Alabama is going to take that seriously.” The Alabama Department of Corrections disputed that the cancellation was a reflection of problems. In a statement, it blamed the late-running court action for the cancellation because prison officials “had a short timeframe to complete its protocol.” Prison officials said they called off Smith’s execution for the night after they were unable to get the lethal injection underway within the 100-minute window between the courts clearing the way for it to begin and a midnight deadline when the death warrant expired for the day. The U.S. Supreme Court cleared the way for Smith’s execution when at about 10:20 p.m., it lifted a stay issued earlier in the evening by the 11th U.S Circuit Court of Appeals. But the state decided about an hour later that the lethal injection would not happen that evening. “We have no concerns about the state’s ability to carry out future lethal injection procedures,” the Alabama Department of Corrections said in an emailed statement. “The department will continue to review its processes, as it routinely does following each execution, to identify areas of improvement.” Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey also blamed Smith’s last-minute appeals as the reason “justice could not be carried out” U.S District Judge R. Austin Huffaker Jr. on Friday granted a request from Smith’s lawyers to visit with Smith and take photographs of his body. He also ordered the state to preserve notes and other materials related to what happened in the failed execution. Smith’s attorneys said they believe he may have been strapped to a gurney for four hours even though his final appeals were still underway. “Mr. Smith no doubt has injuries from the attempted execution — and certainly physical and testimonial evidence that needs to be preserved — that can and should be photographed and/or filmed,” lawyers for Smith wrote. Smith, who was scheduled to be put to death for the murder-for-hire slaying of a preacher’s wife in 1988, was returned to death row at Holman Prison after surviving the attempt, a prison official said. His lawyers declined to comment Friday morning. Corrections Commissioner John Hamm said prison staff tried for about an hour to get the two required intravenous lines connected to Smith, 57. Hamm said they established one line but were unsuccessful with a second line, which is required under the state’s protocol as a backup, after trying several locations on Smith’s body. Officials then tried a central line, which involves a catheter placed into a large vein. “We were not able to have time to complete that, so we called off the execution,” Hamm said. The initial postponement came after Smith’s final appeals focused on problems with IV lines at Alabama’s last two scheduled lethal injections. Because the death warrant expired at midnight, the state must go back to court to seek a new execution date. Advocacy groups and defense lawyers said Alabama’s continued problems show a need for a moratorium to investigate how the death penalty is carried out in the state. “Once again, the state of Alabama has shown that it is not capable of carrying out the present execution protocol without torture,” federal defender John Palombi, who has represented many death row inmates in the state, said via email Prosecutors said Smith was one of two men who were each paid $1,000 to kill Elizabeth Sennett on behalf of her husband, who was deeply in debt and wanted to collect the insurance. The slaying — and the revelations of who was behind it — rocked the small north Alabama community where it happened in Colbert County and inspired a song called “The Fireplace Poker,” by the Southern rock group Drive-By Truckers. John Forrest Parker, the other man convicted in the slaying, was executed in 2010. Alabama has faced scrutiny over its problems at recent lethal injections. In ongoing litigation, lawyers for inmates are seeking information about the qualifications of the execution team members responsible for connecting the lines. In a Thursday hearing in Smith’s case, a federal judge asked the state how long was too long to try to establish a line, noting at least one state gives an hour limit. The execution of Joe Nathan James Jr. in July took several hours to get underway because of problems establishing an IV line, leading Reprieve US Forensic Justice Initiative, an anti-death penalty group, to claim the execution was botched. In September, the state called off the scheduled execution of Alan Miller because of difficulty accessing his veins. Miller said in a court filing that prison staff poked him with needles for more than an hour, and at one point, left him hanging vertically on a gurney before announcing they were

Alabama calls off execution of Kenneth Smith after difficulties inserting IV

Alabama’s execution of a man convicted in the 1988 murder-for-hire slaying of a preacher’s wife was called off Thursday just before the midnight deadline because state officials couldn’t find a suitable vein to inject the lethal drugs. Alabama Department of Corrections Commissioner John Hamm said prison staff tried for about an hour to get the two required intravenous lines connected to Kenneth Eugene Smith, 57. Hamm said they established one line but were unsuccessful with a second line after trying several locations on Smith’s body. Officials then tried a central line, which involves a catheter placed into a large vein. “We were not able to have time to complete that, so we called off the execution,” Hamm said. It is the second execution since September the state has canceled because of difficulties with establishing an IV line with a deadline looming. The U.S. Supreme Court cleared the way for Smith’s execution when at about 10:20 p.m., it lifted a stay issued earlier in the evening by the 11th U.S Circuit Court of Appeals. But the state decided about an hour later that the lethal injection would not happen that evening. The postponement came after Smith’s final appeals focused on problems with intravenous lines at Alabama’s last two scheduled lethal injections. Because the death warrant expired at midnight, the state must go back to court to seek a new execution date. Smith was returned to his regular cell on death row, a prison spokesperson said. Prosecutors said Smith was one of two men who were each paid $1,000 to kill Elizabeth Sennett on behalf of her husband, who was deeply in debt and wanted to collect on insurance. The slaying, and the revelations over who was behind it, rocked the small north Alabama community Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey blamed Smith’s last-minute appeals for the execution not going forward as scheduled. “Kenneth Eugene Smith chose $1,000 over the life of Elizabeth Dorlene Sennett, and he was guilty, no question about it. Some three decades ago, a promise was made to Elizabeth’s family that justice would be served through a lawfully imposed death sentence,” Ivey said. “Although that justice could not be carried out tonight because of last minute legal attempts to delay or cancel the execution, attempting it was the right thing to do.” Alabama has faced scrutiny over its problems at recent lethal injections. In ongoing litigation, lawyers for inmates are seeking information about the qualifications of the execution team members responsible for connecting the lines. In a Thursday hearing in Smith’s case, a federal judge asked the state how long was too long to try to establish a line, noting at least one state gives an hour limit. The execution of Joe Nathan James Jr. took several hours to get underway because of problems establishing an IV line, leading an anti-death penalty group to claim the execution was botched. In September, the state called off the scheduled execution of Alan Miller because of difficulty accessing his veins. Miller said in a court filing that prison staff poked him with needles for more than an hour, and at one point, they left him hanging vertically on a gurney before announcing they were stopping. Prison officials have maintained the delays were the result of the state carefully following procedures. Sennett was found dead on March 18, 1988, in the home she shared with her husband on Coon Dog Cemetery Road in Alabama’s Colbert County. The coroner testified that the 45-year-old woman had been stabbed eight times in the chest and once on each side of the neck. Her husband, Charles Sennett Sr., who was the pastor of the Westside Church of Christ, killed himself when the murder investigation focused on him as a suspect, according to court documents. John Forrest Parker, the other man convicted in the slaying, was executed in 2010. “I’m sorry. I don’t ever expect you to forgive me. I really am sorry,” Parker said to the victim’s sons before he was put to death. According to appellate court documents, Smith told police in a statement that it was “agreed for John and I to do the murder” and that he took items from the house to make it look like a burglary. Smith’s defense at trial said he participated in the attack, but he did not intend to kill her, according to court documents. In the hours before the execution was scheduled to be carried out, the prison system said Smith visited with his attorney and family members, including his wife. He ate cheese curls and drank water but declined the prison breakfast offered to him. Smith was initially convicted in 1989, and a jury voted 10-2 to recommend a death sentence, which a judge imposed. His conviction was overturned on appeal in 1992. He was retried and convicted again in 1996. The jury recommended a life sentence by a vote of 11-1, but a judge overrode the recommendation and sentenced Smith to death. In 2017, Alabama became the last state to abolish the practice of letting judges override a jury’s sentencing recommendation in death penalty cases, but the change was not retroactive and therefore did not affect death row prisoners like Smith. The Equal Justice Initiative, an Alabama-based nonprofit that advocates for inmates, said Smith stands to become the first state prisoner sentenced by judicial override to be executed since the practice was abolished. The U.S. Supreme Court on Wednesday denied Smith’s request to review the constitutionality of his death sentence on those grounds. Republished with the permission of The Associated Press.

Execution set in murder-for-hire of preacher’s wife

Alabama is preparing to execute a man convicted in the 1988 murder-for-hire slaying of a preacher’s wife, even though a jury recommended he receive life imprisonment instead of a death sentence. Kenneth Eugene Smith, 57, is scheduled to receive a lethal injection at a south Alabama prison on Thursday evening. Prosecutors said Smith was one of two men who were each paid $1,000 to kill Elizabeth Sennett on behalf of her husband, who was deeply in debt and wanted to collect on insurance. Elizabeth Sennett was found dead on March 18, 1988, in the couple’s home on Coon Dog Cemetery Road in Alabama’s Colbert County. The coroner testified that the 45-year-old woman had been stabbed eight times in the chest and once on each side of the neck. Her husband, Charles Sennett Sr, who was the pastor of the Westside Church of Christ in Sheffield, killed himself one week after his wife’s death when the murder investigation started to focus on him as a suspect, according to court documents. ADVERTISEMENT Smith’s final appeals focused on the state’s difficulties with intravenous lines at the last two scheduled lethal injections. One execution was carried out after a delay, and the other was called off as the state faced a midnight deadline to get the execution underway. Smith’s attorneys also raised the issue that judges are no longer allowed to sentence an inmate to death if a jury recommends a life sentence. John Forrest Parker, the other man convicted in the slaying, was executed in 2010. “I’m sorry. I don’t ever expect you to forgive me. I really am sorry,” Parker said to the victim’s sons before he was put to death. According to appellate court documents, Smith told police in a statement that it was, “agreed for John and I to do the murder” but that he just took items from the house to make it look like a burglary. Smith’s defense at trial said he agreed to beat up Elizabeth Sennett but that he did not intend to kill her, according to court documents. The U.S. Supreme Court on Wednesday denied Smith’s request to review the constitutionality of his death sentence. Smith was initially convicted in 1989, and a jury voted 10-2 to recommend a death sentence, which a judge imposed. His conviction was overturned on appeal in 1992. He was retried and convicted again in 1996. This time, the jury recommended a life sentence by a vote of 11-1, but a judge overrode the jury’s recommendation and sentenced Smith to death. In 2017, Alabama became the last state to abolish the practice of letting judges override a jury’s sentencing recommendation in death penalty cases, but the change was not retroactive and therefore did not affect death row prisoners like Smith. The Equal Justice Initiative, an Alabama-based nonprofit that advocates for inmates, said that Smith stands to become the first state prisoner sentenced by judicial override to be executed since the practice was abolished. Smith filed a lawsuit against the state seeking to block his upcoming execution because of reported problems at recent lethal injections. Smith’s attorneys pointed to a July execution of Joe Nathan James Jr., which an anti-death penalty group claimed was botched. The state disputed those claims. A federal judge dismissed Smith’s lawsuit last month, but also cautioned prison officials to strictly follow established protocol when carrying out Thursday’s execution plan. In September, the state called off the scheduled execution of inmate Alan Miller because of difficulty accessing his veins. Miller said in a court filing that prison staff poked him with needles for over an hour, and at one point, they left him hanging vertically on a gurney before announcing they were stopping for the night. Prison officials said they stopped because they were facing a midnight deadline to get the execution underway. Republished with the permission of The Associated Press.

Attorneys seek information about halted execution of Alan Miller

Attorneys for an Alabama inmate, who had his lethal injection called off because of intravenous line difficulties, said they want to see information, such as the names and qualifications of execution team members, to understand what went awry. Judge R. Austin Huffaker, Jr. held a hearing Wednesday on the request for information regarding the attempted execution of Alan Miller in September. “We’re trying to understand what went wrong and why,” Mara Klebaner, an attorney representing Miller, told the judge. The Alabama attorney general’s office has asked to keep some of the information secret, or under a protective seal, citing security concerns. Miller had his lethal injection aborted in September after officials tried for more than an hour to connect an intravenous line. Alabama Corrections Commissioner John Hamm told reporters the execution was halted because “accessing the veins was taking a little bit longer than we anticipated,” and the state did not have sufficient time to get the execution underway by a midnight deadline. The state is now seeking a second execution date for Miller. Miller’s attorneys are trying to block the state from attempting a second lethal injection. Huffaker did not issue an immediate ruling but said he was inclined to require the state to turn over the names to Miller’s lawyers. A state attorney argued it was a security risk because of the possibility the names might be leaked. She suggested the people only be identified only by pseudonyms as they are questioned by Miller’s attorneys. “There is a genuine safety concern for these individuals,” Assistant Attorney General Audrey Jordan said. Huffaker said pseudonyms would make it difficult for Miller’s attorneys to research their backgrounds or determine whether the people were being truthful during depositions. He agreed with the state that the names didn’t need to be shared with Miller, noting he had little ability to punish the death row inmate if he violated a confidentiality order. Huffaker also appeared skeptical of a statement in a court filing by the attorney general’s office claiming the execution hadn’t gotten underway. Deputy Attorney General James Houts said it was the state’s contention that the execution doesn’t get underway until the death warrant is read in the execution chamber and the drugs begin flowing. Klebaner said that claim “defies reality.” Klebaner said they have gotten little substantive information from the state, while Houts said they are working as quickly as they can. Huffaker cautioned the state to act in good faith with the information requests. “If I see stonewalling… we are going to be back here having a talk,” Huffaker told attorneys for the state. Republished with the permission of The Associated Press.

Attorneys: Alan Eugene Miller endured ‘torture’ during execution attempt

An Alabama inmate said prison staff poked him with needles for over an hour as they tried to find a vein during an aborted lethal injection last month. At one point, they left him hanging vertically on a gurney before state officials made the decision to call off the execution. Attorneys for 57-year-old Alan Eugene Miller wrote about his experience during Alabama’s September 22 execution attempt in a court filing made last week. Miller’s attorneys are trying to block the state from attempting a second lethal injection. Two men in scrubs used needles to repeatedly probe Miller’s arms, legs, feet, and hands. At one point, using a cell phone flashlight to help their search for a vein, according to the October 6 court filing. The attorneys called Miller the “only living execution survivor in the United States” and said Alabama subjected Miller “to precisely the unnecessary and wanton infliction of pain that the Eighth Amendment was intended to prohibit.” Alabama has asked the state Supreme Court to set a new execution date for Miller, saying the execution was canceled only because of a time issue as the state faced a midnight deadline to get the lethal injection underway. “Despite this failed execution, the physical and mental torture it inflicted upon Mr. Miller, and the fact that Defendants have now botched three lethal injection executions in just four years, Defendants relentlessly seek to execute Mr. Miller again—presumably by lethal injection,” attorneys for Miller wrote, referencing an execution that was canceled and another that took three hours to get underway. “What then, in Defendants’ view, is a constitutional amount of time to spend stabbing someone with needles in an attempt to kill them?” his attorneys wrote. The 351-pound (159-kilogram) inmate testified in an earlier court hearing that medical workers always have difficulty accessing his veins, and that is why he wanted to be executed by nitrogen hypoxia, a newly approved execution method that the state has yet to try. Miller said he was led into the execution chamber at 10 p.m., about an hour after the U.S. Supreme Court lifted an injunction that had been blocking the lethal injunction, and was strapped to the gurney at about 10:15 p.m. After the two men used needles to probe various parts of his body for a vein, also using a phone flashlight to help, Miller told the men, “he could feel that they were not accessing his veins, but rather stabbing around his veins.” Later, a third man then began slapping his neck in an apparent attempt to look for a vein. The three men in scrubs stopped their probing and left the chamber after there was a loud knock on a death chamber window from the state’s observation room, according to the court filing. A prison officer then raised the gurney to a vertical position. Miller said the wall clock read 11:40 p.m., and he estimated that he hung there for about 20 minutes before he was let down and told that his execution was canceled for the evening. “Mr. Miller felt nauseous, disoriented, confused, and fearful about whether he was about to be killed, and was deeply disturbed by his view of state employees silently staring at him from the observation room while he was hanging vertically from the gurney. Blood was leaking from some of Mr. Miller’s wounds,” the motion stated. Miller was sentenced to death after being convicted of a 1999 workplace rampage in which he killed Terry Jarvis, Lee Holdbrooks, and Scott Yancy. “Due to the lateness of the hour, the Alabama Department of Corrections was limited in the number of attempts to gain intravenous access it could make. ADOC made the decision to halt its efforts to obtain IV access at approximately 11:30 p.m., resulting in the expiration of the court’s execution warrant,” the state attorney general’s office wrote in the request for a new date. This is at least the third time Alabama has acknowledged problems with vein access during a lethal injection. The state’s July execution of Joe Nathan James took more than three hours to get underway. Alabama called off the 2018 execution of Doyle Hamm after being unable to establish an intravenous line. Republished with the permission of The Associated Press.

Alabama sets execution date for Kenneth Eugene Smith

Alabama has set a November execution date for a man convicted in the 1988 murder-for-hire killing of a pastor’s wife. The scheduled execution follows criticism over the state’s last two lethal injection attempts, including one that was called off after the execution team had trouble finding a vein. Kenneth Eugene Smith, 57, is set to die at Holman Correctional Facility on November 17, according to a Friday order from the Alabama Supreme Court. Smith was sentenced to death for the killing of Elizabeth Dorlene Sennett, a 45-year-old grandmother and pastor’s wife. Prosecutors said Smith was one of two men who were each paid $1,000 to kill Sennett on behalf of her husband, the Rev. Charles Sennett, who was deeply in debt and wanted to collect on insurance. Elizabeth Sennett was found dead on March 18, 1988, in the couple’s home in Colbert County. The coroner testified that she had been stabbed eight times in the chest and once on each side of the neck. The pastor killed himself a week later. Smith maintained it was the other man who stabbed Elizabeth Sennett, according to court documents. Smith was initially convicted in 1989, and a jury voted 10-2 to recommend a death sentence, which a judge imposed. His conviction was overturned on appeal in 1992. He was retried and convicted again in 1996. This time, the jury recommended a life sentence by a vote of 11-1, but a judge overrode the jury’s recommendation and sentenced Smith to death. Alabama no longer allows a judge to override a jury’s recommendation. In 2017, Alabama became the last state to abolish the practice of letting judges override a jury’s sentencing recommendation in death penalty cases, but the change was not retroactive and therefore did not affect death row prisoners like Smith. John Forrest Parker, the other man that prosecutors said was paid to kill Elizabeth Sennett, was executed in 2010. When asked if he had any final words, Parker turned his head to face Mike and Charles Sennett, the victim’s sons, and said, “I’m sorry. I don’t ever expect you to forgive me. I really am sorry.” Alabama last month called off the execution of Alan Miller because of difficulty accessing the inmate’s veins. Alabama Corrections Commissioner John Hamm told reporters that “accessing the veins was taking a little bit longer than we anticipated,” and the state did not have sufficient time to get the execution underway by a midnight deadline. That was at least the third time Alabama has acknowledged problems with venous access during a lethal injection. The state’s July execution of Joe Nathan James took more than three hours to get underway. And, in 2018, Alabama called off the execution of Doyle Hamm after being unable to establish an intravenous line. Republished with the permission of The Associated Press.

Judge: State must preserve evidence from halted execution

A federal judge on Friday ordered Alabama to preserve records and medical supplies associated with a lethal injection attempt after the prison system acknowledged multiple attempts to access the inmate’s veins before calling off the execution. U.S. District Judge R. Austin Huffaker Jr. issued the order at the request of the inmate’s lawyers who are trying to gather more information about what happened during Alabama’s attempt to execute Alan Miller, 57. Miller was sentenced to death after being convicted of a 1999 workplace rampage in which he killed Terry Jarvis, Lee Holdbrooks, and Scott Yancy. The U.S. Supreme Court cleared the way for the execution shortly after 9 p.m. Thursday and state officials said they determined at about 11:30 p.m. that the could not start the execution by a midnight deadline. Huffaker ordered the Alabama Department of Corrections to locate and preserve all evidence related to the attempted execution, including notes, emails, texts, and used medical supplies such as syringes, swabs, scalpels, and IV-lines. He also granted a request from Miller’s attorney to visit him and photograph what they said are, “injuries from the attempted execution.” During a Friday morning hearing conducted by telephone conference, Huffaker asked the state what was going on in the almost 150 minutes that elapsed after the Supreme Court said the execution could proceed. An attorney for the state told the judge the execution team began preparations at about 10 p.m. and made multiple attempts to connect the IV line but she did not indicate exactly how long the state tried. They stopped trying to gain venous access at about 11:20 p.m, she said. Alabama Corrections Commissioner John Hamm told reporters early Friday morning that “accessing the veins was taking a little bit longer than we anticipated” and the state did not have sufficient time to get the execution underway by a midnight deadline. “Due to time constraints resulting from the lateness of the court proceedings, the execution was called off once it was determined the condemned inmate’s veins could not be accessed in accordance with our protocol before the expiration of the death warrant,” Hamm said. This is at least the third time Alabama has acknowledged problems with venous access during a lethal injection. The state’s July execution of Joe Nathan James took more than three hours to get underway. Alabama called off the 2018 execution of Doyle Hamm after being unable to establish an intravenous line. “The Alabama Department of Corrections verges somewhere between malpractice and butchery,” said Bernard Harcourt, a lawyer who represented Doyle Hamm. “What it demonstrates is we really shouldn’t be given this incompetent bureaucrats the power over life and death.” Miller’s execution was called off after a legal fight on whether the state lost Miller’s paperwork requesting a different execution method. When Alabama authorized nitrogen hypoxia as an execution method, state law gave inmates a brief window to request it. Miller testified at an earlier court hearing that he wanted nitrogen because he dislikes needles and medical staff often have trouble finding a blood vessel to draw blood. Republished with the permission of The Associated Press.

Kay Ivey says Alan Miller’s victims did not choose to die by bullets

Gov. Kay Ivey commented late Thursday on the cancellation of the execution of Alan Eugene Miller after a federal appeals court refused to lift an injunction on the execution. “In Alabama, we are committed to law and order and upholding justice,” Ivey said in a press release. “Despite the circumstances that led to the cancellation of this execution, nothing will change the fact that a jury heard the evidence of this case and made a decision. It does not change the fact that Mr. Miller never disputed his crimes. And it does not change the fact that three families still grieve. We all know full well that Michael Holdbrooks, Terry Lee Jarvis, and Christopher Scott Yancey did not choose to die by bullets to the chest. Tonight, my prayers are with the victims’ families and loved ones as they are forced to continue reliving the pain of their loss.” Alabama Department of Corrections Commissioner John Hamm visited with the victims’ families prior to updating the press after the cancellation and relayed to them the governor’s prayers and concerns. The cancellation of Miller’s execution followed a 2-to-1 decision by the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rejection of Alabama’s attempt to proceed with Miller’s execution. Miller has asked to die from nitrogen hypoxia instead of by lethal injection. The state says that it is not prepared to use the nitrogen hypoxia method yet and is, however, capable of killing by lethal injection. The court refused to lift the injunction by federal district Judge R. Austin Haffaker Jr. on the execution preventing the state from executing Miller. Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall has stated that the state is appealing the ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court. Miller, age 57, was convicted of murdering Holbrooks, Jarvis, and Yancey in a workplace rage attack. Miller claims that the victims were spreading rumors about him. Gov. Ivey anticipates that the execution will be rescheduled as early as possible. To connect with the author of this story, or to comment, email brandonmreporter@gmail.com.