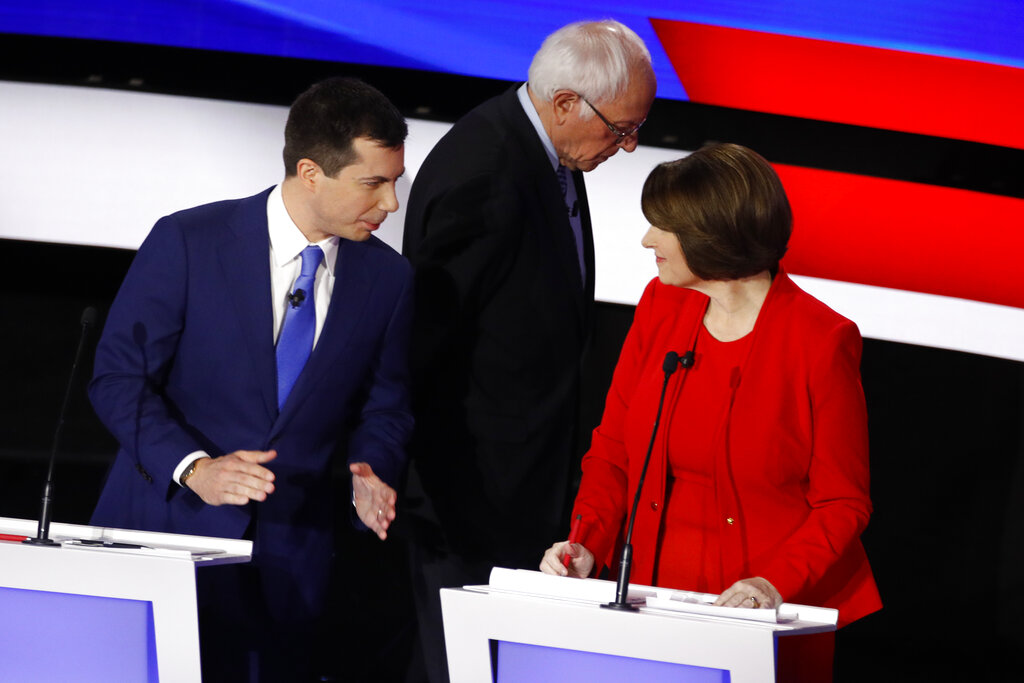

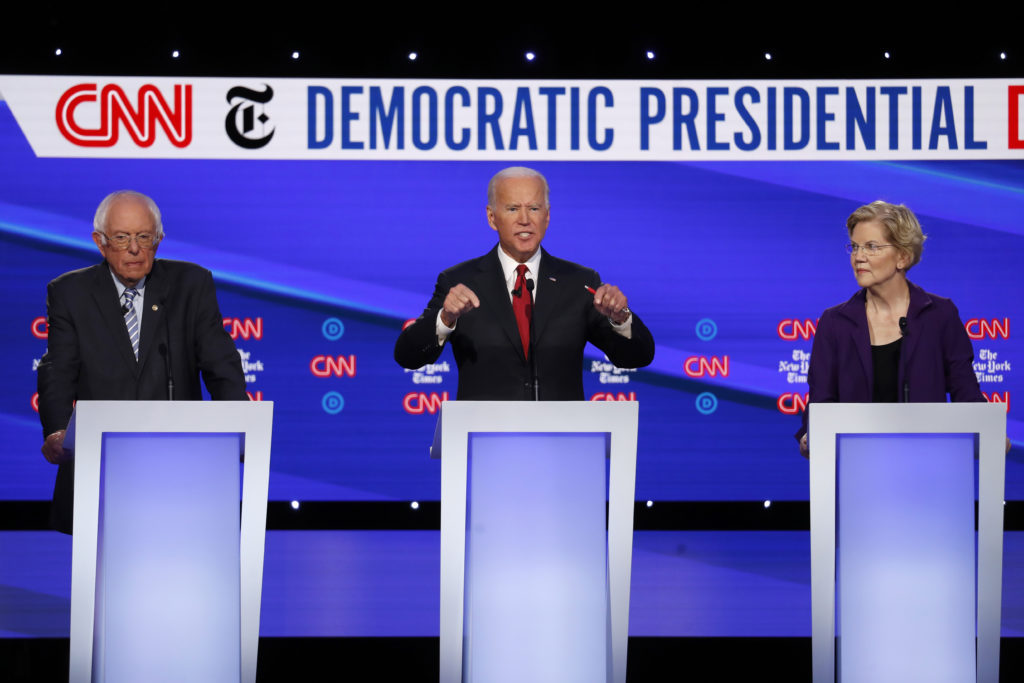

Key takeaways from Democratic presidential debate in Iowa

There were several notable moments in the debate.

‘Fail Not:’ What to watch ahead of Donald Trump’s Senate trial

There are a lot of uncertainties in the yet to be scheduled impeachment trial.

2020 Democratic race is wide open in Iowa as caucuses near

Iowa has a solid record of backing the ultimate Democratic nominee.

Elusive Quest for Momentum is On as Democrats Dash to Iowa

No candidate is a clear leader as the Iowa caucuses draw near.

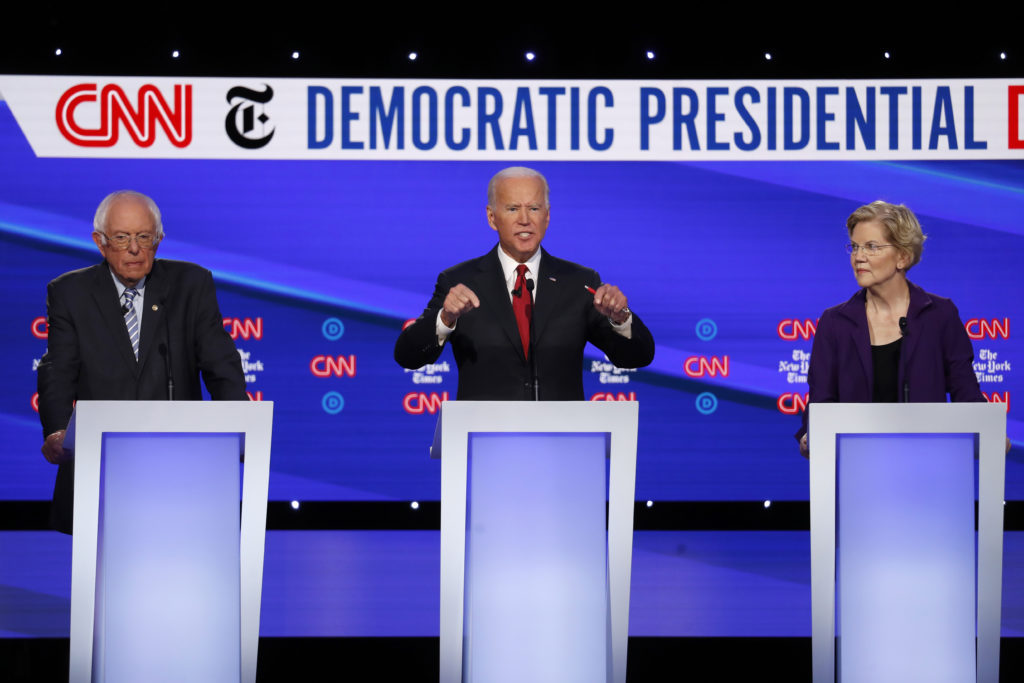

No sign of Donald Trump’s replacement for obamacare

As a candidate for the White House, Donald Trump repeatedly promised that he would “immediately” replace President Barack Obama’s health care law with a plan of his own that would provide “insurance for everybody.” Back then, Trump made it sound that his plan — “much less expensive and much better” than the Affordable Care Act — was imminent. And he put drug companies on notice that their pricing power no longer would be “politically protected.” Nearly three years after taking office, Americans still are waiting for Trump’s big health insurance reveal. Prescription drug prices have edged lower, but with major legislation stuck in Congress it’s unclear if that relief is the start of a trend or merely a blip. Meantime the uninsured rate has gone up on Trump’s watch, rising in 2018 for the first time in nearly a decade to 8.5 percent of the population, or 27.5 million people, according to the Census Bureau. “Every time Trump utters the words ACA or Obamacare, he ends up frightening more people,” said Andy Slavitt, who served as acting administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services during the Obama administration. He’s “deepening their fear of what they have to lose.” White House officials argue that the president is improving the health care system in other ways, without dismantling private health care. White House spokesman Judd Deere noted Trump’s signing of the “Right-to-Try” act that allows some patients facing life-threatening diseases to access unapproved treatment, revamping the U.S. kidney donation system and the FDA approving more generic drugs as key improvements. Trump has also launched a drive to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic. “The president’s policies are improving the American health care system for everyone, not just those in the individual market,” Deere said. But as Trump gears up for his reelection campaign, the lack of a health care plan is an issue that Democrats believe they can use against him. Particularly since he’s still seeking to overturn “Obamacare” in court. This month, a federal appeals court struck down the ACA’s individual mandate, the requirement that Americans carry health insurance, but sidestepped a ruling on the law’s overall constitutionality. The attorneys general of Texas and 18 other Republican-led states filed the underlying lawsuit, which was defended by Democrats and the U.S. House. Texas argued that due to the unlawfulness of the individual mandate, “Obamacare” must be entirely scrapped. Trump welcomed the ruling as a major victory. Texas v. United States appears destined to be taken up by the Supreme Court, potentially teeing up a constitutional showdown before the 2020 presidential election. In a letter Monday to Democratic lawmakers, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi singled out the court case. “The Trump administration continues to firmly support the recent ruling in the 5th Circuit, which they hope will move them one step closer to obliterating every protection and benefit of the Affordable Care Act,” Pelosi wrote, urging Democrats to keep health care front and center in 2020. Accused of trying to dismantle his predecessor’s health care law with no provision for millions who depend on it, Trump and senior administration officials have periodically teased that a plan was just around the corner. In August, the administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Seema Verma, said officials were “actively engaged in conversations and working on things,” while Trump adviser Kellyanne Conway suggested that same month an announcement was on the horizon. In June, Trump told ABC News that he’d roll out his “phenomenal health care plan” in a couple of months, and that it would be a central part of his reelection pitch. The country is still waiting. Meantime Trump officials say the administration has made strides by championing transparency on hospital prices, pursuing a range of actions to curb prescription drug costs, and expanding lower-cost health insurance alternatives for small businesses and individuals. One of Trump’s small business options — association health plans — is tied up in court. And taken together, the administration’s health insurance options are modest when compared with Trump’s original goal of rolling back the ACA. Since Trump has not come through on his promise of a big plan, internecine skirmishes among 2020 Democratic presidential hopefuls have largely driven the health care debate in recent months. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren are leading the push among liberals for a “Medicare for All” plan that would effectively end private health insurance while more moderate candidates, like Joe Biden, Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar, advocate for what they contend is a more attainable expansion of Medicare. Brad Woodhouse, a former Democratic National Committee official and executive director of the Obamacare advocacy group Protect Our Care, said it is important for Democrats to “put down the knives they’ve been wielding against one another on health care.” “Instead turn their attention to this president and Republicans who are trying to take it away,” Woodhouse counseled. Some Democratic hopefuls appear to be doing just that. During a campaign stop in Memphis, Tennessee. this month, former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg called out Trump on health care, saying the president is “determined to throw Americans off the boat, without giving them a lifeline.” Polling suggests Trump’s failure to follow through on his promise to deliver a revamped health care system could be a drag on his reelection effort. Voters have consistently named health care as one of their highest concerns in polling. And more narrowly, a recent Gallup-West Health poll found that 66 percent of adults believe the Trump administration has made little or no progress curtailing prescription drug costs. Prescription drug prices did drop 1 percent in 2018, according to nonpartisan experts at U.S. Health and Human Services. That was the first such price drop in 45 years, driven by declines for generic drugs, which account for nearly 9 out of 10 prescriptions dispensed. Prices continued to rise for brand-name drugs, although at a more moderate pace. Trump’s broadsides against the pharmaceutical industry might well have helped check prices, though drug companies have

Takeaways from the democratic presidential debate

Democratic presidential candidates offered two very different debates during their final forum of 2019. In the first half, they spent much of their time making the case for their electability in a contest with President Donald Trump. The second half was filled with friction over money in politics, Afghanistan and experience. MONEY TALKED The candidates jousted cordially over the economy, climate change and foreign policy. But it was a wine cave that opened up the fault lines in the 2020 field. That wine cave, highlighted in a recent Associated Press story, is where Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Indiana, recently held a big-dollar Napa Valley fundraiser, and Sen. Elizabeth Warren — who along with Sen. Bernie Sanders has eschewed fundraisers in favor of small-dollar grassroots donations — slammed him for it. “Billionaires in wine caves should not pick the next president of the United States,” Warren said. Buttigieg struck back, noting that he was the only person on the stage who was not a millionaire or billionaire. He said that if Warren donated to him he’d happily accept it even though she’s worth “ten times” what he is. He also added that Warren had only recently sworn off big money donations. “These purity tests shrink the stakes of the most important election,” Buttigieg snapped. It was an unusually sharp exchange between Warren and Buttigieg. The two have been sparring as Warren’s polling rise has stalled out and Buttigieg poached some of her support among college-educated whites. And Warren was not the only one going after Buttigieg. Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota hit him on another front, namely what she said was his lack of experience compared to her Senatorial colleagues on stage. Still, the divide is about more than Warren and Buttigieg. It’s about the direction of the party — whether it should become staunchly populist, anti-corporate and solely small-dollar funded, or rely on traditional donors, experience and ideology. IMPEACHMENT AS PROXY The first question in the debate was about impeachment. But the answer from the Democratic candidates was about electability. Most candidates had no answer to their party’s biggest challenge — getting Trump’s voters to abandon him over his conduct. Warren talked about one of her favorite themes, “corruption” in Washington. Sanders talked about having to convince voters Trump lied to them about helping the working class. Klobuchar, a former prosecutor, laid out the case against Trump as if she were giving the opening statement in his Senate trial. Buttigieg said the party can’t “give into that sense of hopelessness” that the GOP-controlled Senate will simply acquit Trump because Republican voters aren’t convinced. But Buttigieg didn’t provide any other hope. Only businessman Andrew Yang gave an explanation for why impeachment hasn’t changed minds. “We have to stop being obsessed about impeachment, which strikes many Americans like a ball game where you know what the score will be.” Instead, Yang said, the party has to grapple with the issues that got Trump elected — the loss of good jobs. BIDEN STEADY Former Vice President Joe Biden has held steady throughout the Democratic race as one of the top two or three candidates by almost any measure. He has done that with debate performances described as flat, uneven, and uninspired. He had a better night Thursday, even on a question about of one of his views that causes fellow Democrats to groan: that he can work with Republicans once he beats Trump in November. “If anyone has reason to be angry with the Republicans and not want to cooperate it’s me, the way they’ve attacked me, my son, my family,” Biden said, a reference to Trump’s push to investigate his son Hunter that led to the president’s impeachment. “I have no love. But the fact is we have to be able to get things done and when we can’t convince them, we go out and beat them.” Unlike others on the stage, he said pointedly that he doesn’t believe it’ll be impossible to ever work together with the other party. “If that’s the case,” Biden said, “we’re dead as a country.” He came close to trouble by initially saying he would not commit to a running for a second term, them quickly said that would be presumptuous to presume a first one. AMERICAN ROLE IN THE WORLD Is the greatest danger to America’s foreign interests and alliances coming from within the White House? Democratic presidential candidates faulted Trump on multiple fronts for his failure to lead in key disputes and areas of international friction, including in the Middle East and China. Buttigieg said Trump was “echoing the vocabulary” of dictators in his relentless attacks on the free press. Klobuchar said the president had “stood with dictators over innocents.” And Tom Steyer warned against isolating the U.S. from China, saying the two nations needed to work together on climate change. On Israel, Biden argued that Trump had played to fears and prejudices and stressed that a two-state solution was needed for peace to ever be achieved. The former vice president said Washington must rebuild alliances “which Trump has demolished.’” With China, “We have to be firm. We don’t have to go to war,” Biden said. “We have to be clear, “This is as far as you go, China,” he added. YANG’S PRO MOVES In June, Yang was a political punchline. During the first few Democratic debates, the entrepreneur, who has never before run for office, looked lost onstage, struggling to be heard over the din of nine other candidates. But on Thursday night, Yang looked like a pro. When the candidates debated complex foreign policy, Yang talked about his family in Hong Kong, the horror of China’s crackdown there and how to pressure them to respect human rights. When some candidates equivocated over whether nuclear energy should be used to combat climate change, Yang had the last word when he said: “We need to have everything on the table in a crisis situation.” And when a moderator noted that Yang was

Only 7 democrats will be on the stage for the last presidential debate of 2019

A winnowed field of Democratic presidential contenders takes the debate stage for a sixth and final time in 2019, as candidates seek to convince anxious voters that they are the party’s best hope to deny President Donald Trump a second term next year. Thursday night’s televised contest ahead of Christmas will bring seven rivals to heavily Democratic California, the biggest prize in the primary season and home to 1 in 8 Americans. And, coming a day after a politically divided House impeached the Republican president, the debate will underscore the paramount concern for Democratic voters: Who can beat Trump in November? With voters distracted by the holidays and the impeachment proceedings in Washington, the debate in Los Angeles could turn out to be the least watched so far. Viewership has declined in each round though five debates, and even campaigns have grumbled that the candidates would rather be on the ground in early voting states than again taking the debate stage. The lack of a clear front-runner reflects the uncertainty gripping many voters. Would Trump be more vulnerable to a challenge from the party’s liberal wing or a candidate tethered to the centrist establishment? Should the pick be a man or a woman, or a person of color? The Democratic field is also marked by wide differences in age, geography and wealth, and the party remains divided over issues including health care and the influence of big-dollar fundraising. There will be a notable lack of diversity onstage compared to earlier debates. For the first time this cycle, the debate won’t feature a black or Latino candidate. The race in California has largely mirrored national trends, with former Vice President Joe Biden, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders and Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren clustered at the top of the field, followed by South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg, Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar, businessman Andrew Yang and billionaire philanthropist Tom Steyer. Conspicuously missing from the lineup at Loyola Marymount University on Thursday will be former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, a billionaire who is unable to qualify for the contests because he is not accepting campaign donations. But even if he’s not on the podium, Bloomberg has been felt in the state: He’s running a deluge of TV advertising in California to introduce himself to voters who probably know little, if anything, about him. Bloomberg’s late entry into the contest last month highlighted the overriding issue in the contest, electability, a sign of the unease within the Democratic Party about its crop of candidates and whether any is strong enough to unseat an incumbent president. The eventual nominee will be tasked with splicing together the party’s disparate factions — a job Hillary Clinton struggled with after defeating Sanders in a long and bitter primary fight in 2016. Biden adviser Symone Sanders said to expect another robust exchange on health care. “This is an issue that is not going away and for good reason, because it is an issue that in 2018 Democrats ran on and won,” she said. Jess O’Connell with Buttigieg’s campaign said the candidate will “be fully prepared to have an open and honest conversation about where there are contrast between us and the other candidates. This is a really important time to start to do that. Voters need time to understand the distinctions between these candidates.” The key issues: health care and higher education. The unsettled race has seen surges at various points by Biden, Warren, Sanders and Buttigieg, though it’s become defined by that cluster of shifting leaders, with others struggling for momentum. California Sen. Kamala Harris, once seen as among the top tier of candidates, shelved her campaign this month, citing a lack of money. And Warren has become more aggressive, especially toward Buttigieg, as she tries to recover from shifting explanations of how she’d pay for “Medicare for All” without raising taxes. In a replay of 2016, the shifting race for the Democratic nomination has showcased the rift between the party’s liberal wing, represented in Sanders and Warren, and candidates parked in or near the political center, including Biden, Buttigieg and Bloomberg. Two candidates who didn’t make the stage will still make their presence felt for debate watchers with ads reminding viewers they’re still in the race. New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker and former Housing Secretary Julián Castro are airing television ads targeted to primary voters during the debate. Booker’s is his first television ad, and in it he says even though he’s not on the debate stage, “I’m going to win this election anyway.” It’s airing as part of a $500,000 campaign, running in Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada and South Carolina, as well as New York, Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles. A pro-Booker super PAC is also going up with an ad in Iowa highlighting positive reviews of Booker’s past debate performances. Meanwhile, Castro is running an ad, in Iowa, in which he argues the state should no longer go first in Democrats’ nominating process because it doesn’t reflect the diversity of the Democratic Party. Both candidates failed to hit the polling threshold to qualify for the debates and have in recent weeks become outspoken critics of what they say is a debate qualification process that favors white candidates over minorities. By Kathleen Ronayne and Michael R. Blood Associated Press Associated Press writer Michelle L. Price in Las Vegas contributed to this report. Catch up on the 2020 election campaign with AP experts on our weekly politics podcast, “Ground Game.” Republished with the Permission of the Associated Press.

Turbulence shakes democrats going into final debate of 2019

Seven Democratic presidential candidates will stand on stage this week in Los Angeles, a pool of survivors who have withstood almost a year on the campaign trail, sustained attacks from rivals in both major political parties and five rounds of high-pressure debates. And while the field has been effectively cut down from more than 20 in the span of six months, a deepening sense of volatility is settling over the Democratic primary on the eve of the sixth and final debate of 2019. The remaining candidates, those in the debate and some trying to compete from outside, are grappling with unprecedented distraction from Washington, questions about their core principles and new signs that the party’s energized factions are turning against each other. Lest there be any doubt about the level of turbulence in the race, it’s unclear whether Thursday’s debate will happen at all given an unsettled labor union dispute that might require participants to cross a picket line. All seven candidates have said they would not do so. The Democratic dilemma is perhaps best personified by Elizabeth Warren, whose progressive campaign surged through the late summer and fall but is suddenly struggling under the weight of nagging questions about her health care plan, her ability to compete against President Donald Trump and her very authenticity as a candidate. Boyd Brown, a South Carolina-based Democratic strategist who recently decided to back Joe Biden only after his preferred candidate, Beto O’Rourke, was forced from the race, likened Warren’s position to that of someone falling down a mountain grasping for anything to slow her descent. “She’s got real problems,” Brown said. Warren has avoided conflict with her Democratic rivals for much of the year, but she has emerged as the chief antagonist of the leading candidates in the so-called moderate lane, former Vice President Joe Biden and Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Indiana. Seven weeks before Iowa’s Feb. 3 caucus, the Massachusetts senator is attacking both men with increasing frequency for being too willing to embrace Republican ideas and too cozy with wealthy donors. Those close to Warren hope the strategy will allow her to shift the conversation away from her own health care struggles back to her signature wealth tax and focus on corruption. Yet she could not escape questions about her evolving position on Medicare for All as she campaigned in Iowa over the weekend. When asked about health care, Warren told a crowd of roughly 180 people in the Mississippi River town of Clinton, Iowa, about a plan to expand insurance coverage without immediately moving to a universal, government-run system. She promised that those who wanted government health insurance could buy it before finally concluding, “At the end of my first term, we’ll vote on Medicare for All.” The next question came from a man who said he was on Medicare and mostly happy about it, but had lingering issues. “You call it Medicare for All and it’s better. Can’t you change the name?” he asked of her proposal. “I like your suggestion,” Warren responded, in a tone suggesting she wasn’t entirely joking. “Let’s call it health care for everybody.” She later added, “Let’s call it better than Medicare for All. I’m in.” Even entertaining a name change seemed to mark yet another shift for Warren, who first co-sponsored Medicare for All in 2017, but began pivoting away from the proposal after experts questioned the plan she released in October to pay for it without raising middle-class taxes. She subsequently released a “transition plan” promising to get Medicare for All approved by Congress by the end of her third year as president while relying on existing insurance plans, including those established by Obamacare, to expand health coverage in the interim. Warren’s Democratic critics suggest her evolution on the issue has stalled her momentum because it goes beyond a policy dispute and raises broader questions about what may be the most important personal quality in politics: authenticity. Indeed, Buttigieg, Biden and other rivals have seized on her shifts. Even Bernie Sanders, Warren’s progressive ally and Medicare for All’s author, seemed to pile on by promising to send a full bill to Congress implementing the measure during the first week of his administration. Without naming any of his rivals, Biden adviser Symone Sanders said candidates would not succeed in shifting the conversation away from health care this week even if they wanted to. She said to expect another “robust exchange” on the issue, which “is not going away and for good reason, because it is an issue that in 2018 Democrats ran on and won.” Tough questions for Warren haven’t just come from her rivals. Since Thanksgiving, she’s shortened her typically 30-minute and more stump speech to around 10 minutes and used the extra time to take more audience questions — only to be forced further on the defensive about health care. Barton Wright, a 69-year-old technical writer, pressed Warren on Medicare for All at a recent event in Rochester, New Hampshire, noting after the event that he wants a deeper explanation. “It just sounds awful,” Wright said. “It sounds ‘like Hemlock for All’ for people who don’t like Medicare. And that’s a lot of people.” Even after questioning Warren, however, Wright said he was helping her campaign and still plans to vote for her. Meanwhile, Buttigieg, the surprise member of the top-tier, is grappling with issues of his own that expose another fissure between the moderate and progressive wings of the party. Protesters aligned with Warren and Sanders tracked him across New York City last week banging pots and pans and calling him “Wall Street Pete” as he continued his aggressive courtship of wealthy donors. The 37-year-old seemed genuinely confused by the protests, which he was forced to acknowledge during at least one Manhattan fundraiser because the noise outside was so loud. As he faced supporters in Seattle over the weekend, Buttigieg acknowledged that the intra-party attacks will almost certainly continue, although he tried to downplay the intensity of the

Can 2020 democratic candidates break through the turkey coma?

Presidential politics move fast. What we’re watching heading into a new week on the 2020 campaign: Days to Iowa caucuses: 70 Days to general election: 344 THE NARRATIVE The presidential race comes to a an abrupt pause this week as voters and candidates alike shift their focus to food, football and family. The bar will be high for any new narrative to emerge over the Thanksgiving holiday, which means the Democratic primary will be locked in a four-way muddle at the top as newly announced candidate Michael Bloomberg spends big to exploit questions about his rivals and to attack President Donald Trump. THE BIG QUESTIONS Can anyone break through the food coma? With just 10 weeks until voting begins, very few candidates in the crowded Democratic race can afford another week without making progress in addressing their glaring liabilities. The same could be said for Trump, who’s facing the prospect of impeachment as his party struggles with a revolt from women and suburban voters. But there’s likely little the candidates can do on a holiday week that they haven’t already done to change the direction of the dinner table conversation. Can he buy love? The 2020 contest’s latest shiny object, but this has more than 30 billion reasons to be taken seriously on his first week out as a candidate. Bloomberg, whose worth is estimated at $30 billion to $50 billion, is dumping more than $30 million into a first-week advertising blitz that will almost certainly show up during your Thanksgiving football watching. The early investment has officially broken the record for the largest single-week ad buy in political history. If this kind of investment doesn’t move the needle for the New York billionaire, it’s fair to wonder if anything will. Room for another moderate at the table? For all the candidates who need to do well in Iowa in just 70 days, we’re only aware of two who are having Thanksgiving dinner there. That would be Kamala Harris, who you’ll remember said she was “moving to Iowa,” and Amy Klobuchar, who serves neighboring Minnesota in the Senate but has struggled to persuade primary voters to embrace her Midwestern pragmatism. Klobuchar is scheduled to have Thanksgiving dinner with staff at the home of a former state party chairwoman, while Harris will cheer runners at a Des Moines turkey trot and spend time with seniors. Can Pete Buttigieg take the next step? He has proven he belongs in the top tier after another strong debate performance and rising poll numbers on the ground in Iowa. But the 37-year-old small-city mayor has virtually no path to the nomination unless he dramatically improves his standing with black voters. He opens the week back in Iowa, where he’s betting everything that a strong showing in the opening primary contest will convince skeptical minority voters that he’s electable. It’s a tough road, but absent a dominant front-runner he must be taken seriously. THE FINAL THOUGHT Ten weeks before voting begins, the Democratic primary is truly wide open. There are four candidates clumped together in the top tier, and a candidate with essentially an unlimited budget just entered the race. Buckle up. 2020 Watch runs every Monday and provides a look at the week ahead in the 2020 election. By Steve Peoples AP National Politics Writer. Follow Peoples at https://twitter.com/sppeoples. Catch up on the 2020 election campaign with AP experts on our weekly politics podcast, “Ground Game.” Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

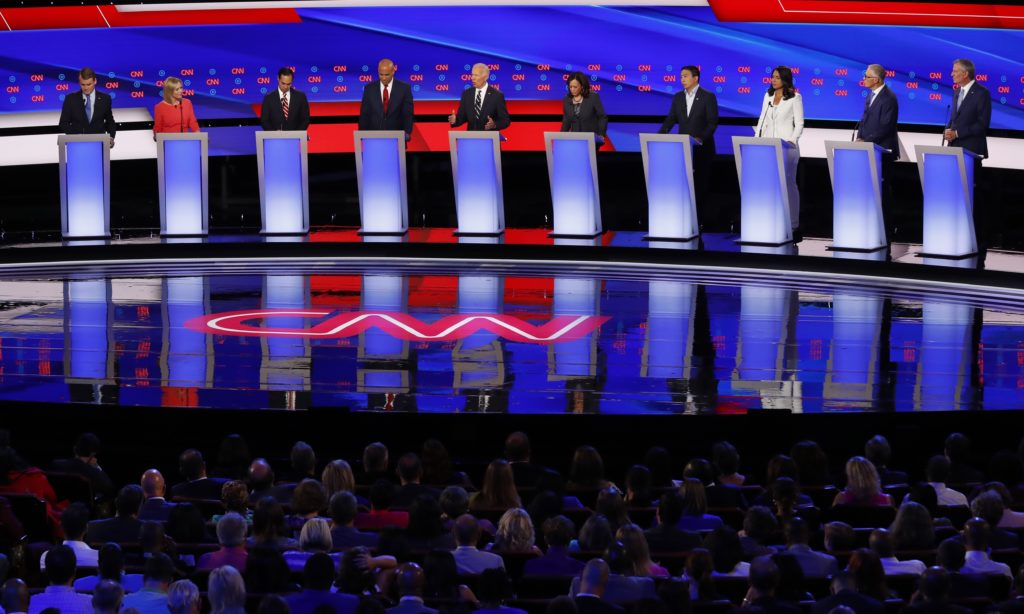

Takeaways from the democratic presidential debate

Democrats spent more time making the case for their ability to beat President Donald Trump than trying to defeat each other in their fifth debate Wednesday night. Civil in tone, mostly cautious in approach, the forum did little to reorder the field and may have given encouragement to two new entrants into the race, Mike Bloomberg and Deval Patrick. Here are some key takeaways. IMPEACHMENT CLOUD HOVERS The impeachment inquiry of President Donald Trump took up much of the oxygen early in the debate. The questions about impeachment did little to create much separation in a field that universally condemns the president. The candidates tried mightily to pivot to their agenda. Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren talked about how a major Trump donor became the ambassador at the heart of the Ukraine scandal, and reiterated her vow to not reward ambassadorships to donors. Former Vice President Joe Biden tried to tout the investigation as a measure of how much Trump fears his candidacy. Impeachment is potentially perilous to the Democratic candidates for two reasons. A Senate trial may trap a good chunk of the field in Washington just as early states vote in February. It also highlights a challenge for Democrats since Trump entered the presidential race in 2015 — shifting the conversation from Trump’s serial controversies to their own agenda. Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders warned, “We cannot simply be consumed by Donald Trump, because if you are you’re going to lose the election.” OBAMA COALITION Perhaps more than in any debate so far, Democrats explicitly acknowledged the importance of black and other minority voters. California Sen. Kamala Harris said repeatedly that Democrats must reassemble “the Obama coalition” to defeat Trump. Harris, one of three black candidates running for the nomination, highlighted black women especially, arguing that her experiences make her an ideal nominee. Another black candidate, New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, added: “I’ve had a lot of experience with black voters. … I’ve been one since I was 18.” Neither Booker nor Harris, though, has been able to parlay life experiences into strong support in the primary, in no small part because of Biden’s strong standing in the black community. Biden’s standing is also a barrier to other white candidates, including South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg, who is surging in overwhelmingly white Iowa but struggling badly with black voters in Southern states like South Carolina that have proven critical to previous Democratic nominees. Buttigieg acknowledged as much, saying he welcomes “the challenge of connecting with black voters in America who don’t yet know me.” The exchanges show that candidates seemingly accept the proposition that the eventual nominee will have to put together a racially diverse coalition to win, and that those whose bases remain overwhelmingly white (or just too small altogether) aren’t likely to be the nominee. CLIMATE CRISIS GETS AIR The climate crisis, which Democratic voters cite as a top concern, finally gained at least some attention. There were flashes of the debate Wednesday night, as billionaire environmental activist Tom Steyer swiped at Biden by suggesting the former vice president wants an inadequate, piecemeal approach to the crisis. Biden hit right back, reminding Steyer that he sponsored climate legislation as a senator in the 1980s while Steyer built his fortune in part on investments in coal. Buttigieg turned a question about the effects of Trump’s policies on farmers into a call for the U.S. agriculture sector to become a key piece of an emissions-free economy. But those details seem less important than the overall exchange — or lack thereof. Perhaps it’s the complexities of the policies involved. Or perhaps it’s just the politics. Whatever the case, the remaining field simply doesn’t seem comfortable or willing to push climate policy to the forefront, and debate moderators don’t either. HEALTH CARE GROUNDHOG DAY Before every debate, Democratic presidential campaigns aides lay out nuanced, focused arguments their candidates surely will make on the stage. And every debate seems to evolve quickly into an argument over health care. So it was again. Within minutes of the start, Warren found herself on the defensive as she explained she still supports a single-payer government run insurance system — “Medicare for All” — despite her recent modified proposal to get there in phases. Not to be outdone, Sanders reminded people that he’s the original Senate sponsor of the “Medicare for All” bill that animates progressives. “I wrote the damn bill,” he quipped. Again. Biden jumped in to remind his more liberal rivals that their ideas would not pass in Congress. The former vice president touted his commitment to adding a government insurance plan to existing Affordable Care Act exchanges that now sell private insurance policies. The debate highlights a fundamental tension for candidates: Democratic voters identify health care as their top domestic policy concern, but they also tell pollsters their top political priority in the primary campaign is finding a nominee who can defeat Trump. The top contenders did nothing to settle the argument Wednesday, instead offering evidence that the ideological tug-of-war will remain until someone wins enough delegates to claim the nomination. DID YOU HEAR THE ONE … The debate was so genial that some of the most memorable moments were the candidates’ well-rehearsed jokes. Asked what he’d say to Russian President Vladimir Putin if he’s elected to the White House, technology entrepreneur Andrew Yang said his first words would be, “Sorry I beat your guy.” Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar drew laughs for an often-repeated anecdote about how she set a record by raising $17,000 from ex-boyfriends during her first campaign. She also pushed back at fears of a female candidacy by saying, “If you think a woman can’t beat Donald Trump, Nancy Pelosi does it every day.” Booker, criticizing Biden for not agreeing to legalize marijuana, said, “I thought you might have been high when you said it.” And Harris may have issued the zinger of the night at the president when discussing his nuclear negotiations with North Korea: “Donald Trump got

7 questions heading into the 2020 democratic debate

New uncertainty hangs over the Democratic presidential primary as 10 candidates meet on the debate stage once again. No longer is there a clear front-runner. The fight for African American voters is raging. And there are growing concerns that impeachment may become a distraction from the primary. Those issues and more will play out Wednesday night when the Democratic Party’s top 10 face off in Atlanta just 75 days before primary voting begins. Seven big questions heading into the debate, to be carried on MSNBC: WHO IS THE FRONT-RUNNER? Turbulent polling across the early voting states has created a murky picture of the top tier of the 2020 class. As much as Joe Biden is still a front-runner, so are Elizabeth Warren, Pete Buttigieg and Bernie Sanders. The question is who gets the front-runner treatment in Wednesday’s debate. Warren was under near-constant attack last month as a new leader. Will Warren continue to face the heat, or will the ascendant Buttigieg or weakening Biden take more hits? HOW WILL OBAMA PLAY? Former President Barack Obama, the most popular Democrat in America, inserted himself into the 2020 primary in recent days by warning candidates against moving too far to the left. His comments create a challenge for Warren and Sanders and an opening for moderates Buttigieg, Biden and Amy Klobuchar to attack. At the same time, Obama’s involvement offers a powerful reminder of the massive role African Americans will play in the presidential nomination process. As we know, all candidates not named Biden have serious work to do when it comes to winning over the black vote. Race and Obama’s legacy could play a major role in shaping the action. WHAT SAY YOU, IMPEACHMENT JURY? They have all come out in favor of impeachment — some more aggressively than others — but it’s noteworthy that five of the 10 Democrats onstage will serve as jurors in the Senate impeachment trial should the House vote to impeach President Donald Trump. It’s a complicated topic for Democrats. Some senators worry that a prospective impeachment trial will interfere with their ability to court voters early next year. Others fear that impeachment could hurt their party’s more vulnerable candidates in down-ballot elections next year. Either way, what the prospective jurors do or don’t say on the debate stage could be relevant if and when the Senate holds an impeachment trial, which is increasingly likely. WILL THEY BASH THE BILLIONAIRES? Never before has wealth been under such aggressive attack in a presidential primary election. And with one billionaire onstage and another likely to join the field in the coming days, the billionaire bashing could reach new heights. Tom Steyer has largely gone under the radar, but the even wealthier Michael Bloomberg has generated tremendous buzz as he steps toward a run of his own. Of the two, only Steyer will be onstage, but expect Bloomberg’s shadow in particular to generate passionate arguments about wealth and the role of money in politics. WILL SOMEONE STAND UP FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT? Biden continues to be the favorite of many establishment Democrats, but his underwhelming candidacy has created an opening for another pragmatic-minded Democrat to step up. That’s why former Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick and Bloomberg are moving into the race. Buttigieg stepped aggressively into the establishment lane in the last debate, but many donors and elected officials remain skeptical of the 37-year-old small-city mayor’s chances. The opportunity is there for lower-tier candidates including Kamala Harris, Klobuchar and Steyer. DOES SHE HAVE A PLAN FOR THAT? No single issue has dominated the initial Democratic primary debates more than health care, and it’s safe to assume that will be the case again Wednesday night. And no one has more riding on that specific debate than Warren, who hurt herself last month by stumbling through questions about the cost of her single-payer health care plan. Given that policy specifics make up the backbone of her candidacy, she can’t afford another underwhelming performance on the defining policy debate of the primary season. Expect the policy-minded senator to have a new strategy this time around. CAN THEY SAVE THEMSELVES? New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, Hawaii Rep. Tulsi Gabbard, businessman Andrew Yang and Steyer are under enormous pressure to break out given their status as the only candidates onstage who haven’t yet qualified for the December debate. They likely won’t have the same number of opportunities to speak as their higher-polling rivals, but these are dire times for the underdogs. They need to do something if they expect to stay relevant in the 2020 conversation. By Steve Peoples AP National Political Writer. Catch up on the 2020 election campaign with AP experts on our weekly politics podcast, “Ground Game.” Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Takeaways: Elizabeth Warren under fire, 70s club ignores the age issue

A dozen democratic presidential candidates participated in a spirited debate over health care, taxes, gun control and impeachment. Takeaways from the three-hour forum in Westerville, Ohio: WARREN’S RISE ATTRACTS ATTACKS Sen. Elizabeth Warren found Tuesday that her rise in the polls may come with a steep cost. She’s now a clear target for attacks, particularly from more moderate challengers, and her many plans are now being subjected to much sharper scrutiny. Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar and South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg slammed her for not acknowledging, as Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders has, that middle-class taxes would increase under the single-payer health plan she and Sanders favor. “At least Bernie’s being honest with this,” Klobuchar said. “I don’t think the American people are wrong when they say what they want is a choice,” Buttigieg told Warren. His plan maintains private insurance but would allow people to buy into Medicare. Candidates also pounced on Warren’s suggestion that only she and Sanders want to take on billionaires while the rest of the field wants to protect them. Former Texas Rep. Beto O’Rourke told Warren it didn’t seem as though she wanted to lift people up and she is “more focused on being punitive.” And they piled onto her signature proposal, a 2 percent wealth tax to raise the trillions of dollars needed for many of her ambitious proposals. Technology entrepreneur Andrew Yang noted that such a measure has failed in almost every European country where it’s been tried. Sen. Kamala Harris of California even went after Warren for not backing Harris’ call for Twitter to ban President Donald Trump. THAT 70s SHOW The stage included three 70-something candidates who would be the oldest people ever elected to a first term as president — including 78-year-old Sanders, who had a heart attack this month. Moderators asked all three how they could do the job. None really addressed the question. Sanders invited the public to a major rally he’s planning in New York City next week and vowed to take the fight to corporate elites. Biden promised to release his medical records before the Iowa caucuses next year and said he was running because the country needs an elder statesman in the White House after Trump. Warren, whose campaign has highlighted her hours-long sessions posing for selfies with supporters, promised to “out-organize and outlast” any other candidate, including Trump. Then she pivoted to her campaign argument that Democrats need to put forth big ideas rather than return to the past, a dig at Biden. ONE VOICE ON IMPEACHMENT The opening question was a batting practice fastball for the Democratic candidates: Should Trump be impeached? They were in steadfast agreement. All 12 of them. Largely with variations on the word “corrupt” to describe the Republican president. Warren was asked first if voters should decide whether Trump should stay in office. She responded, “There are decisions that are bigger than politics.” Biden, who followed Sanders, offered a rare admission: “I agree with Bernie.” The only hint of dissonance came from Rep. Tulsi Gabbard of Hawaii, who was one of the last Democratic House members to back an impeachment inquiry. She lamented that some Democrats had been calling for Trump’s impeachment since right after the 2016 election, undermining the party’s case against him. KLOBUCHAR: MINNESOTA NOT-SO-NICE Klobuchar has faded into the background in previous debates, but she stood out on the crowded stage. She also went on the attack. She chided Yang for seeming to compare Russian interference in the 2016 election to U.S. foreign policy. But her main barbs were reserved for Warren. “I appreciate Elizabeth’s work but, again, the difference between a plan and a pipe dream is something you can actually get done,” she said. After Warren seemed to suggest other candidates were protecting billionaires, Klobuchar pounced. “No one on this stage wants to protect billionaires,” Klobuchar said. “Even the billionaire doesn’t want to protect billionaires.” That was a reference to investor Tom Steyer, who had agreed with Sanders’ condemnation of billionaires and called for a wealth tax — despite the fact that his wealth funded his last-minute campaign to clear the debate thresholds and appear Tuesday night. Klobuchar also forcefully condemned Trump’s abandonment of the Kurds in Syria. BOOKER THE PEACEMAKER New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker has been trying to campaign on the power of love and unity. It hasn’t vaulted him to the top of the polls, but it drew perhaps the biggest cheers from the crowd Tuesday night. As candidates bickered over their tax plans, Booker shut it down. “We’ve got one shot to make Donald Trump a one-term president and how we talk about each other in this debate actually really matters,” he said. “Tearing each other down because we have a different plan is unacceptable.” Later, as candidates tussled over foreign policy and Syria, Booker again tried to bring the debate back to morals. “This president is turning the moral leadership of this country into a dumpster fire,” he said, before launching into a furious condemnation of Trump’s foreign policy. The New Jersey senator’s inability to break out of the pack has puzzled Democrats who long saw him as a top-tier presidential candidate. By Nicholas Riccardi Associated Press Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.