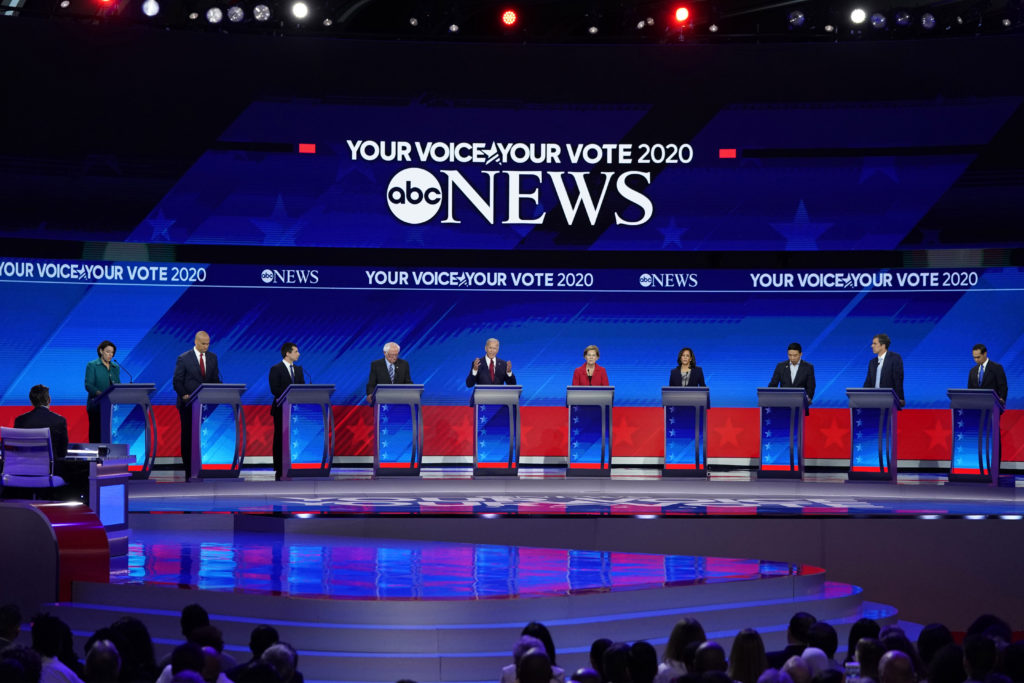

Key takeaways from the 2020 democratic candidates’ debate

Democratic debate night No. 3: Attacks and counter-attacks. Love for one former president, loathing for the current one. A 76-year-old front-runner essentially got called old, and he turned around and called another rival a “socialist.” But will it change the fundamentals of a nominating fight that remains remarkably stable at the top with five months until voting begins? Here’s a look at some takeaways and potential answers: STATUS QUO PREVAILED The third Democratic debate seemed to end in a 10-way tie. Former Vice President Joe Biden was sure-footed (until the end), at least for him and compared with the previous two debates. There were more attacks on President Donald Trump than on each other. No one dominated. Biden took on the most fire, but parried it and, as front-runner, benefits the most from a no-decision. Sen. Bernie Sanders faced sharp criticism about his universal health care plan from several candidates, but his base has demonstrated its loyalty. Sen. Elizabeth Warren was more in the background than in prior debates but didn’t damage herself, and she closed with a compelling personal story. Sens. Kamala Harris and Cory Booker were both crisp but got lost on the crowded stage at times. Mayor Pete Buttigieg, former Rep. Beto O’Rourke and Sen. Amy Klobuchar helped form a sensibility caucus, offering pragmatism and civic-mindedness. Andrew Yang, a tech entrepreneur, spoke eloquently about immigration and assured himself a mention with his proposal to give 10 families $1,000 a month, from his campaign. The normally mild-mannered Julián Castro, a former Housing secretary, decided that attacking Biden, often in personal terms, was one way to get noticed. The likely result: little change in a primary that has been remarkably static for months. FIGHT THAT DIDN’T BREAK OUT The first matchup between Biden and Warren had so much anticipation — and so little fireworks. There were a few criticisms of Warren on health care, though she not directly answer whether her plan would raise taxes on the middle class. During a discussion on trade, Biden even said he agreed with Warren’s call to bring labor to the table. Certainly, the head-to-head confrontation will come if Biden continues as the front-runner and Warren maintains her momentum as perhaps the most likely progressive alternative. But perhaps the two campaigns were right after all when they said privately before the debate that September — five months before the Iowa caucuses — isn’t necessarily the time for a titanic fight at the top of the field. BERNIE BATTERED ON HEALTH CARE Sanders took heavy fire on his single-payer health insurance proposal, with Biden and others hammering the Vermont senator for the cost and the political palatability of effectively eliminating the existing private insurance market. The former vice president went hardest at Sanders when the senator argued that his estimated $30 trillion cost over a decade is cheaper than the “status quo,” which he put at $50 trillion — with most of the money being what Americans spend privately on premiums, co-pays and out-of-pocket costs. Sanders’ argument is that most U.S. households would pay less overall under his system, even if their taxes go up. Biden roared that Sanders would effectively be handing Americans a pay cut, arguing employers who now pay a share of workers’ premiums would pocket that money instead of giving workers raises if the government were to cover all health care costs. Biden punctuated the point with one of the quotes of the night: “For a socialist, you’ve got a lot more confidence in corporate America than I do.” Buttigieg piled on Sanders, too. Buttigieg said he “trusts the American people to make the right decision” between private insurance and a public option. “Why don’t you?” he asked Sanders. OF AGE AND EXPERIENCE At the center of the debate stage were three candidates in their 70s who have had a collective headlock on the upper tier for months. Of the seven younger contenders, Castro, 44, was most explicit in arguing it was time for a new generation — and he specifically targeted the front-runner, 76-year-old Biden. “Our problems didn’t start with Donald Trump,” Castro said in his opening statement. “We won’t solve them by embracing old ideas.” Castro also seemed to allude to speculation about Biden’s mental acuity during an exchange about health care. When Biden denied that his health plan required people to buy into Medicare, Castro exclaimed, “Are you forgetting what you said 2 minutes ago?” He continued to suggest Biden didn’t remember what he’d just said about his own plan. Later, during a discussion about deportations under the Obama administration, Castro mocked Biden for clinging to former President Barack Obama, but then saying he was only vice president when Obama’s conduct was questioned. “He wants to take credit for Obama’s work but not answer any questions,” Castro said. MONEY FOR NOTHING Yang is an unorthodox candidate, and he came to the debate with an offer to match his persona: a proposal to use his campaign funds to pay 10 randomly-selected families $1,000 a month. Yang announced the maneuver in his opening statement. It’s intended to illustrate the center of his quixotic campaign, to provide monthly $1,000 payments to all Americans 18 and over. After lamenting how the country is in thrall to “the almighty dollar,” Yang, 44, urged viewers to go to his campaign website and register for the contest to win the money.His offer drew cheers from the audience and chortles from some of the other candidates onstage. “It’s original, I’ll give you that,” Buttigieg said. By Bill Barrow and Nicholas Riccardi Associated Press. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Democratic debate: Top 2020 contenders finally on same stage

Progressive Democrats Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders share the debate stage for the first time with establishment favorite Joe Biden Thursday night in a prime-time showdown displaying sharply opposing notions of electability in the party’s presidential nomination fight. Biden’s remarkably steady lead in the crowded contest has been built on the idea that the former vice president is best suited to defeat President Donald Trump next year — a contention based on ideology, experience and perhaps gender. Sanders and Warren, meanwhile, have repeatedly criticized Biden’s measured approach, at least indirectly, by arguing that only bold action on key issues like health care, the economy and climate change can build the coalition needed to win in 2020. The top-tier meeting at center stage has dominated the pre-event talk, yet each of the other seven candidates hopes for a breakout moment with the attention of the nation beginning to increase less than five months before the first primary votes are cast. “For a complete junkie or someone in the business, you already have an impression of everyone,” said Howard Dean, who ran for president in 2004 and later chaired the Democratic National Committee. “But now you are going to see increasing scrutiny with other people coming in to take a closer look.” The ABC News debate is the first limited to one night after several candidates dropped out and others failed to meet new qualification standards. A handful more candidates qualified for next month’s debate, which will again be divided over two nights. Beyond Biden and Sens. Warren and Sanders, the candidates on stage Thursday night include Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar, New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg, California Sen. Kamala Harris, New York businessman Andrew Yang, former Texas Rep. Beto O’Rourke and former Obama administration Housing chief Julian Castro. Viewers will see the diversity of the modern Democratic Party. The debate, held on the campus of historically black Texas Southern University, includes women, people of color and a gay man, a striking contrast to the Republicans. It will unfold in a rapidly changing state that Democrats hope to eventually bring into their column. Perhaps the biggest question is how directly the candidates will go after one another. Some fights that were predicted in previous debates failed to materialize with candidates like Sanders and Warren in July joining forces. The White House hopefuls and their campaigns are sending mixed messages about how eager they are to make frontal attacks on anyone other than Trump. That could mean the first meeting between Warren, the rising progressive calling for “big, structural change,” and Biden, the more cautious but still ambitious establishmentarian, doesn’t define the night. Or that Harris, the California senator, and Buttigieg, the mayor of South Bend, Indiana, look to reclaim lost momentum not by punching rivals but by reemphasizing their own visions for America. Biden, who has led most national and early state polls since he joined the field in April, is downplaying the prospects of a clash with Warren, despite their policy differences on health care, taxes and financial regulation. “I’m just going to be me, and she’ll be her, and let people make their judgments. I have great respect for her,” Biden said recently as he campaigned in South Carolina. Warren says consistently that she has no interest in going after Democratic opponents. Yet both campaigns are also clear that they don’t consider it a personal attack to draw sharp policy contrasts. Warren, who as a Harvard law professor once challenged then-Sen. Biden in a Capitol Hill hearing on bankruptcy law, has noted repeatedly that they have sharply diverging viewpoints. Her standard campaign pitch doesn’t mention Biden but is built around an assertion that the “time for small ideas is over,” an implicit criticism of more moderate Democrats who want, for example, a public option health care plan instead of single-payer or who want to repeal Trump’s 2017 tax cuts but not necessarily raise taxes further. Biden, likewise, doesn’t often mention Warren or Sanders. But he regularly contrasts the price tag of his public option insurance proposal to the single-payer system that Warren and Sanders back. In a pre-debate briefing, Biden campaign officials said he would reject the premise that he’s an incrementalist, either in his long career as a senator and vice president or in his proposals for a would-be presidency. In an apparent rebuke of Warren, known for her policy plans, the advisers said Biden will hit on the idea that “we need more than just plans, we need action, we need progress.” Health care will top the list of examples, they said. They note that Biden’s proposal for a government-run “public option” to compete with private insurance still would be a major market shift, even if it stops short of Sanders’ and Warren’s proposal for a government insurance system that would effectively end the existing private insurance system. And, by extension, the difference may make Biden’s plan more likely to make it through Congress, they contend. There are indirect avenues to chipping away at Biden’s advantages, said Democratic consultant Karen Finney, who advised Hillary Clinton in 2016. Finney noted Biden’s consistent polling advantages on the question of which Democrat can defeat Trump. A Washington Post-ABC poll this week found that among Democrats and Democratic-leaning voters, 45 percent thought Biden had the best chance to beat Trump, though just 24 percent identified him as the “best president for the country” among the primary field. “That puts pressure on the others to explain how they can beat Trump,” Finney said.Voters, she said, “want to see presidents on that stage,” and Biden, as a known quantity, already reaches that threshold. “If you’re going to beat him, you have to make your case.”Harris, said spokesman Ian Sams, will “make the connection between (Trump’s) hatred and division and our inability to get things done for the country.” Buttigieg, meanwhile, will have an opportunity to use his argument for generational change as an indirect attack on the top

2020 Democratic primary field puts diversity in spotlight

The early days of the Democratic primary campaign are highlighting the party’s diversity as it seeks a nominee who can build a coalition to take on President Donald Trump. Of the more than half dozen Democrats who have either moved toward a campaign or declared their candidacy, four are women: Sens. Kirsten Gillibrand of New York, Kamala Harris of California and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Rep. Tulsi Gabbard of Hawaii. Harris is also African-American. Former Obama Cabinet member Julian Castro, who is Latino, has also joined the race. And on Wednesday, Democrat Pete Buttigieg, the 37-year-old mayor of South Bend, Indiana, jumped into the campaign. If he wins the Democratic nomination, he would be the first openly gay presidential nominee from a major political party. He would also be the youngest person ever to become president if he wins the general election. The diversity is likely to expand in the coming weeks as other Democrats enter the race. The field that’s taking shape follows a successful midterm election in which Democrats elected a historically diverse class of politicians to Congress, a pattern they’d like to repeat on the presidential scale. Neera Tanden, president of the liberal Center for American Progress Action Fund, hailed the Democrats’ multiple trailblazing candidates for reflecting that “the central opposition to Trump is around a vision of the country that’s inclusive of all Americans.” “A lot of different people are going to see that they can be part of the Democratic Party” thanks to a field that showcases women, candidates of color, and the first potential LGBT nominee, Tanden said. The primary “hopefully will bring a lot of people into the process,” she added, recalling the high number of voters who engaged in a 2008 Democratic primary that featured a possible female nominee, Hillary Clinton, and the man who would become the first black president, Barack Obama. The array of backgrounds was on display Wednesday when Buttigieg spoke in personal terms about his marriage. “The most important thing in my life — my marriage to Chasten — is something that exists by the grace of a single vote on the U.S. Supreme Court,” Buttigieg told reporters. “So I’m somebody who understands — whether it’s through that or whether it’s through the fact that I was sent to war on the orders of the president — I understand politics not in terms of who’s up and who’s down or some of the other things that command the most attention on the news but in terms of everyday impacts on our lives.” Gillibrand has put her identity as a mother at the core of her campaign, and Harris launched her campaign on this week’s Martin Luther King holiday, a nod to her historic bid to become the first black woman elected president. A number of high-profile candidates remain on the sidelines, including two who would further bolster the diversity of the 2020 field: Sens. Cory Booker of New Jersey, who is black, and Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota. Booker, who’s widely expected to join the presidential fray in the coming days, visited the pivotal early-voting state of South Carolina this week for public events honoring King and private meetings with local activists. Klobuchar is set to speak at the University of Pennsylvania on Thursday about her work on the Senate Judiciary Committee, where Booker and Harris also are members. The affable Midwesterner recently told MSNBC that her family “is on board” if she opts to run in 2020, though she’s offered little clarity about her timetable to announce a decision. Though Klobuchar would be the fifth major female candidate in the Democratic primary, female candidates shouldn’t be shoehorned into a “narrative” dominated by their identity that excludes the policies they’re championing, said Virginia Kase, CEO of the League of Women Voters. Kase pushed back at one popular 2018 narrative in a recent interview, noting that that “every year is the year of the woman — the reality is that we’ve always been major contributors” in the electoral process. Rashad Robinson, executive director of the civil rights-focused nonprofit Color of Change, said in an interview that the diversity of the Democratic field is “a great thing and we should celebrate it,” adding that, “Our work is always about changing the rules — changing the rules of who can run and who can rule and who can lead is incredibly important.” But in addition to those “unwritten rules,” Robinson pointed to the urgency of changing the “written rules” of American life, adding that “diversity alone does not mean structures and policies and practices that have held so many back will change” overnight. Meanwhile, three white male candidates who could scramble the race — former Vice President Joe Biden, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont, and former Texas Rep. Beto O’Rourke — are still weighing their own presidential plans. Biden addressed a key vulnerability in his potential candidacy this week by publicly airing regret about his support for a 1994 crime bill that’s had particularly negative effects on African-American communities, while Sanders built his own new connections to black voters during a trip to South Carolina. As Biden mulls a run for president, his allies have been sending supporters a memo that could serve as a rationale for a campaign. The memo hails Biden’s long track record in politics and argues that at a time of “unprecedented political chaos” during Trump’s administration, Biden would offer “trustworthy, compassionate leadership.” O’Rourke, for his part, continues to gauge his own future amid pundits’ criticism about blog posts he published during a recent road trip through multiple states. The 46-year-old Texan acknowledged that he’s been “in and out of a funk” following his departure from Congress after losing a high-profile Senate race in November, sparking questions about the luxury of his indecision given the family wealth and network of passionate backers he can lean on. As the Democratic field is poised to become more diverse, Republicans say Trump will run for re-election based on his

Lawmakers struggling to develop a response to Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin

Congress is producing an unusual outpouring of bills, resolutions and new sanctions proposals to push back at President Donald Trump’s approach to Vladimir Putin, shore up relations with NATO allies and prevent Russian interference in the midterm election. But it remains uncertain if any of their efforts will yield results. Lawmakers are struggling with internal party divisions as well as their own onslaught of proposals as they try to move beyond a symbolic rebuke of Trump’s interactions with the Russian president and exert influence both at home and abroad. And while many Democrats are eager for quick votes, some Republicans prefer none at all. As Trump and Putin weigh another face-to-face meeting, lawmakers in both parties — particularly in the Senate — appear motivated to act. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell issued a rare warning that Russia “better quit messing around” in U.S. elections as he tasked two Senate committees to start working on sanctions-related legislation and other measures to deter Russia. In the House, Speaker Paul Ryan joined McConnell in saying that Putin would not be welcome on Capitol Hill, though he did not push forward any Russia-related legislation before his chamber recessed for August. Still, the past few weeks have been one of the rare moments in the Trump era that Republicans and Democrats have jointly asserted the role of Congress as a counterweight to the administration. “You look at the action of Congress since the summit in Helsinki, you find Democrats and Republicans both standing up and saying no,” said Sen. Ben Cardin, D-Md., in an interview on C-SPAN with The Associated Press and The Washington Post. For starters, there’s a bipartisan push from Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., and others to “explicitly prohibit” the president from withdrawing from NATO without Senate approval. Other senators are debating action to prevent meddling in the midterm election. Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., and Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., call the protection of the election system a “national security priority.” Graham said it’s “extremely important that Congress recognize the threat to our electoral system coming from Russia and act in a decisive way.” In addition, legislation from McCain and Cardin would require approval from Congress before Trump could reverse sanctions issued under the Sergei Magnitsky Act, which bans visas for travel and freezes assets of key Russians involved in alleged human rights abuses. Russia’s displeasure at the 2012 Magnitsky Act played into what Trump initially called an “incredible offer” from Putin at the summit to allow U.S. questioning of Russians indicted by the Justice Department for hacking Democratic emails. In return, Putin requested the ability to investigate Americans involved in the Magnitsky Act. McCain called it a “perverse proposal” and Trump has since backed away from it. With some 100 days before the midterm election, some say Congress is not acting fast enough. One bill that has been given a go-ahead nod from McConnell is legislation from Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., and Sen. Chris Van Hollen, D-Md., that attempts to warn Putin off more election interference by setting up tough new sanctions on Russia if it does try to intervene. The measure is slowly making its way through the Senate Banking Committee, but some lawmakers in the House and Senate have raised concerns it casts too wide a net and could cause problems for allied nations that do business with Russia. Rubio says he’s willing to adjust the legislation to meet concerns, but says the goal is for Russia to understand there will be a price to pay for further election interference. He adds the legislation was introduced months before the Helsinki summit and isn’t intended to embarrass or attack the president. “I’m deeply concerned about their ability to interfere in our politics,” Rubio said in an interview. “We want them to know what the price is going to be to make that choice.” The legislation would likely see overwhelming support, lawmakers in both parties say. But a vote is not scheduled. Some symbolic measures on Russia have failed to make it out of the starting gate. Already, the Senate has blocked a symbolic resolution from Sen. Jeff Flake, R-Ariz., and Sen. Chris Coons, D-Del., to reaffirm the findings of the American intelligence community that Russia interfered in the 2016 election. Twice over the past two weeks, Republicans objected to motions to advance the measure, saying they prefer a more strategic approach that goes beyond symbolic resolutions. House Democrats were similarly thwarted in their attempts to slap new sanctions on anyone who has interfered in U.S. elections and bolster election security funds to the states as Republicans blocked those votes. Key Republicans are panning more federal spending on election security. The GOP chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee, Alabama Sen. Richard Shelby, said Monday that he worried federal funds would come with “strings attached” that would interfere with elections operations he believes should be left to the states. Ryan says the U.S. has “learned a great deal” about Russian interference. “So, I think we’re far better prepared today than we were just a couple of years ago.” But the Speaker added there’s more for Congress to do. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Babies of senators now welcome in Senate chamber

Who doesn’t like babies? No one in the Senate, apparently — at least not enough to block a historic rules change that passed Wednesday allowing the newborns of members into the chamber. Its passage without objection came despite plenty of concern, some privately aired, among senators of both parties about the threat the tiny humans pose to the Senate’s cherished decorum. “I’m not going to object to anything like that, not in this day and age,” said Sen. Pat Roberts, R-Kan., father of three and grandfather of six. He then noted that a person can stand in the door of the cloakroom, a lounge just off the chamber, and vote. “I’ve done it,” he said. Allowing babies on the Senate floor, he said, “I don’t think is necessary.” Sen. Orrin Hatch, the father of six, grandfather of 14 and great-grandfather of 23, said he had “no problem” with such a rules change. “But what if there are 10 babies on the floor of the Senate?” he asked. The inspiration for the new rule is a small bundle named Maile Pearl, born April 9 to Illinois Democrat Tammy Duckworth —the only sitting senator in U.S. history to give birth. In a statement, Duckworth thanked her colleagues for “helping bring the Senate into the 21st Century by recognizing that sometimes new parents also have responsibilities at work.” Their concerns and more were shared by Republicans and Democrats, according to interviews Wednesday. “It is a big change,” Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., said in a telephone interview, as leaders of both parties sought to clear the new rule without objection, or public discussion. The private reassurances to members of both parties, she said, have “been going on for weeks.” Teleworking is not an option in the Senate, which requires members to vote in person. So Duckworth raised a rare question that split her colleagues more along generational lines than well-worn partisan ones. Duckworth proposed changing the rules to allow senators with newborns — not just Duckworth, and not just women — to bring their babies onto the floor of the Senate. This, recalled Klobuchar, did not go entirely smoothly for the two months she privately took questions about the idea and its potential consequences — diaper changes, fussing and, notably, nursing. Sen. Tom Cotton, father of two, said he has no problem with the rule change. But the Arkansas Republican acknowledged that some of his colleagues do, “so the cloakroom might be a good compromise.” Klobuchar’s answer to that suggestion noted that Duckworth lost both legs and partial use of an arm in Iraq, and mostly gets around by wheelchair. “Yes, you can vote from the doorway of the cloakroom, but how is she going to get to the cloakroom when it’s not wheelchair accessible?” she asked. Some senators proposed making an exception for Duckworth. But her allies said the Senate should make work easier for new parents. “We believe strongly, and she did, that it should be a permanent rules change.” Having 10 babies on the Senate floor, as Hatch suggested, “would be a delight,” Klobuchar said. “We could only wish we had 10 babies on the floor. That would be a delight,” retorted Klobuchar, noting that such a conflagration would probably mean more young senators had been elected in a body where the average age of members tops 60. There was more, voiced privately, Klobuchar said — including whether Duckworth intended to change Maile’s diaper or nurse her new baby on the Senate floor. Most senators, though, were supportive, Klobuchar said. Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., and Rules Committee Chairman Roy Blunt, R-Mo., both fathers, helped or did not stand in the way. McConnell did not answer a reporter’s question Wednesday about whether he had any concerns about babies on the Senate floor. Several others were happy to voice support for the rules change, and could not resist taking a jab at their colleagues. “Why would I object to it? We have plenty of babies on the floor,” joked Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla. But there still was some confusion. Just after the unanimous vote, Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., said it would do the tradition-bound Senate some good to see “a diaper bag next to one of these brass spittoons, which sit on the floor, thank goodness, never used.” Oklahoma Republican James Inhofe took issue with that, saying: “They don’t use diaper bags anymore. They’re disposable diapers.” Diaper bags are generally used to carry clean diapers and other supplies when parents and babies go out. Sometimes, they hold dirty naps until they can be disposed of. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.