Secretary of State’s Office begins legal action to recover unpaid campaign finance fines

The Alabama Secretary of State’s Office is standing up to political action committees and candidate committees who failed to pay their campaign finance fines during the 2018 election cycle. On Thursday, Alabama Secretary of State John Merrill announced he is enforcing a 2015-495 in 2015 law that allows his office to issue fines when Principle Campaign Committees (PCCs) or Political Action Committees (PACs) don’t file their monthly, weekly, or daily campaign finance reports on time. The fines are serve as a deterrent to filing elections late and keeping pertinent donor information away from voters. There are 24 unpaid penalties among the nine noncompliant committees listed below: Burton Leflore Diedre Willis Franklin Edwards John Moton, Jr. Richard Dickerson Roderick Clark Terrence Johnson Veronica Johnson William Hobbs According to state law, all funds collected are deposited directly into the state general fund. The Fair Campaign Practices Act does not protect the people of Alabama when campaigns and their committees avoid transparent reporting of the campaign’s financial activity. This law was established to provide the people of Alabama with a concise report of the financial activity of those seeking public office in Alabama.

Secretary of State’s office recovers over $100,000 in campaign finance fines

Alabamians, like most Americans, want transparency when it comes to politics. Part of that means being able to see who’s funding political candidates. Which is exactly why political candidates and Political Action Committees (PACs) are required to file campaign finance reports. But sometimes those reports aren’t filed on time, or at all. Which is why the state legislature passed act 2015-495 in 2015 that allows the Alabama Secretary of State’s office to issue fines when Principle Campaign Committees (PCCs) or Political Action Committees (PACs) don’t file their monthly, weekly, or daily campaign finance reports on time. The act went into effect with the start of the 2018 Election Cycle and since that time Secretary of State John Merrill‘s office has issued 1,166 penalties or warnings for a total amount of $197,657.84. Thus far, $102,249.05 has been paid. The money not yet paid has either been waived by the Alabama Ethics Commission or the office is still waiting to collect the funds from the committee. According to the Secretary of State’s office, “Penalties are issued to any committee that does not file their campaign finance report by midnight on the date the report is due. Most reports are due by 12:00 p.m. on the 2nd of each month. Committees are required to report all contributions and expenditures incurred by their campaign during the previous month.” Accordingly, penalty amounts increase as the number of late reports increases from the candidate. Additionally, the first report a candidate files late, but within 48 hours of the date the report is due, the committee is given a warning that does not count against them or require a fine be paid. Further, the code specifically states that warnings are not violations of the law. In addition to the warning process, committees have the ability to appeal their penalty to the Alabama Ethics Commission. Of the 1,166 penalties and warnings, 166 have been overturned. Fines paid by committees to the Secretary of State’s office is deposited directly into the state general fund.

Behind the scenes of State Senate fundraising numbers for open seats

Numbers don’t lie. Well… sometimes when it comes to campaigns they do. When you’re just given a “cash on hand” total that figure can be deceiving. Any expert worth their salt will tell you that the devil is in the details. So below is a breakdown of some of the races for Alabama’s open Senate seats. With nine of the 26 Senate Republicans not running for re-election, either to retire or seek higher office, there’s a lot at play and a lot at stake this election. In addition to those nine, one lone Democrat, Sen. Hank Sanders has also announced his retirement and his daughter, Malika Sanders-Fortier, will run in his place. Since January’s campaign finance reports were recently filed, here’s a deeper look at “open” Senate seats up for grabs this year — who’s running, what their spending money on, how much they’re paying consultants, and how much cash they have on hand as they went into February. Here’s who’s running for the “open seats:” (candidates listed in order of total cash on hand): Senate District 2 Incumbent Bill Holtzclaw retiring Tom Butler (R): $44,640.09 Largest campaign expenditure to date: $3,700.00 to the Driscoll Group Amy Wasyluka (D): $7,081.60 Largest campaign expenditure to date: $493.77 to Allied Digital Printing Steve Smith (R): $1,085.56 PAYPAL 2145 HAMILTON Largest campaign expenditure to date: $29.30 to Paypal Michael Smith (D): $1,074.86 Self-loaned campaign $2,000 on Jan. 25, 2018 Senate District 7 Incumbent Paul Sanford retiring Mary Scott Hunter (R): $227,045 Donated $190,457.66 on Oct. 3, 2017 from Mary Scott Hunter Lt. Gov Committee Consultant cost to date: $32,578.09 total —> $6,000.55 (Beshears Solutions); $13,887 (Leverage Public Strategies); $2,050 (Vickie Gesellschap); $8,669.54 (Alexander Cooksey); $971 (Todd Powers); $1,000 (Vulpes Et Leo) Largest campaign expenditure to date: $3,700.00 to Advictory Johnathan Hard (D): $4,367.15 Consultant cost to date: $650 (Red Brick Strategies) Largest campaign expenditure to date: $404.39 to Tennessee Valley Sign Sam Givhan (R): $127,892 Consultant cost to date: $12,810 total —> $9,000 (Red State Strategies); $3,810 (Politically Correct Consulting) Largest campaign expenditure to date: $1,000 to MCREC Deborah Barros (D): $0 Senate District 10 Incumbent Phil Williams retiring (Assumed office in 2010) Mack Butler (R): $140,757 Self-loaned campaign $100,000 on Aug. 28, 2017 Donated $638.10 on Aug. 28, 2017 from Committee to Elect Mack Butler Consultant cost to date: $44,692.90 (Master Image Inc.) Largest campaign expenditure to date: $3269.70 to C&D Catering Andrew Jones (R): $3,472.56 Self-loaned campaign: $6,000 total —> $50 on Oct. 31, 2017; $950 on Dec. 20, 2017; $5,000 on Jan. 1, 2018 Largest campaign expenditure to date: $829.64 to Vistaprint Craig Ford (I): $0 Senate District 13 Incumbent Gerald Dial running for Ag Commissioner (Assumed office in 2010) Randy Price (R): $64,041 Self-loaned campaign $334.72 on Sept. 30, 2017 Consultant cost to date: $4,789.40 (Politically Correct Consulting) Largest campaign expenditure to date: $5,000 to Sinclair Broadcasting Mike Sparks (R): $18,840 Self-loaned campaign: $2,288.25 total —> $1004.25; $245.00; $1039.00 Tim Sprayberry (R): $5,110.81 Self-loaned campaign: $2,986.28 total —> $634.05 on Sept. 29, 2017; $1028.39 on Oct. 31, 2017; $642.94 on Nov. 30, 2017; $680.90 on Dec. 29, 2017 Largest campaign expenditure to date: $120 to Bama Carry/Chambers County Darrell Turner (D): $0 Senate District 15 Incumbent Slade Blackwell retiring (Assumed office in 2010) Miranda Carter (R): $0 Laura Casey (D):0 Dan Roberts (R): $0 Senate District 25 Incumbent Dick Brewbaker retiring (Assumed office in 2010) Charles “Will” Barfoot (R): $73,561.59 Self-loaned campaign: $50,000 on June 30, 2017 Consultant cost to date: $18,302 (Virtus Solutions) Largest campaign expenditure to date: $3,289.00 at Boosters Incorporated Ronda Walker (R): $37,543.88 Donated $7,156.54 on June 30, 2017 from Ronda Walker for County Commissioner fund Gave self loan of $10,000 on June 30, 2017 Consultant cost to date: $7,340.02 total —> $2,974.27 (Newman and Associates); $1,865.75 (Alexander Cooksey); $2,500.00 (Leverage Public Strategies) Largest campaign expenditure to date: $1,422.47 at Simply Mac David A. Sadler (D): $0 Frank Snowden (D): $0 Senate District 32 Incumbent Trip Pittman retiring (Assumed office in 2007) David Northcutt (R): $215,089.91 Self-loaned campaign: $73,000 total —> $19,000 on May 16, 2017; $3,000 on June 7, 2017; $50,000 on June 30, 2017; $1,000 on Nov. 22, 2017 Consultant cost to date: $6,425.24 (Red State Strategies) Largest campaign expenditure to date: $1,969.28 to Postmark Inc. Bill Roberts (R): $68,411.41 Self-loaned campaign $50,000 on July 31, 2017 Donated $28,298.32 on June 17, 2017 from the Bill Roberts Representative Campaign Largest campaign expenditure to date: $2,834.00 to Action Printing Chris Elliott (R): $44,662.63 Consultant cost to date: $20,043.63 total —> $8,640 (Catalyst and Associates); $11,403.63(Strategy Inc.) Largest campaign expenditure to date: $501.22 to Boost Promotional Branding Jeff Boyd (R): $38,315.39 Self-loaned campaign: $1,333.64 total —> $631.52 on June 15, 2017; $702.12 on June 26, 2017 Largest contributor Russell Robinson: $25,000 Largest campaign expenditure to date: $3,034.82 to Sign Man Senate District 34 Incumbent Rusty Glover running for Lt. Governor (Assumed office in 2006) Jack Williams (R): $190,942.26 Self-loaned campaign $100,000 on July 6, 2017 Consultant cost to date: $1,760.00 (Interstate Solutions) Largest campaign expenditure to date: $5,793.85 to Interstate Printing and Graphics Inc. (owned by Interstate Solutions) Currently serves as Alabama State Representative for District 102 Mark Shirey (R): $8,773.44 Self-loaned campaign $500 on Nov. 21, 2017 Consultant cost to date: $6,230.30 (Red State Strategies) Largest campaign expenditure to date: $4,683.40 to ABC Signs and Shirts Senate District 35 Incumbent Bill Hightower running for Governor (Assumed office in 2013) David Sessions (R): $133,124.09 Donated $32,011.07 on Oct. 2, 2017 from the David Sessions State Representative Committee Consultant cost to date: $11,212.84 (Strategy Inc.) Largest campaign expenditure to date: $49 to USPS Currently serves as Alabama State Representative for District 105 Tom Holmes (D): $4,897.26 Largest campaign expenditure to date: $1,205.60 at Griffice Printing Company *Largest campaign expenditure to date excludes candidate qualifying fees

Secretary of State John Merrill says 92 candidates, PACS violate Alabama finance rules

Alabama Secretary of State John Merrill says 92 political candidates and Political Action Committees (PACs) have broken campaign finance rules. Annually, by January 31, candidates that spend or raise more than $1,000 must file campaign finance reports showing campaign contributions and expenditures. In 2017, more than 1,000 candidates and PACs were required to file their 2016 Annual Report. As of Monday, 92 have not yet taken the steps necessary to reach full compliance. Merrill on Monday publicly released of all the candidates and PACs who missed the January deadline. “Our intention in releasing these names to the public is to further encourage candidates and PACs to bring their filings into compliance allowing the citizens of our state to review the extent of their fiscal responsibility,” Merrill said in a press release. At this time, no administrative penalties exist for those who missed the deadline. Beginning with the 2018 Election Cycle, which begins in June, administrative penalties will be levied. $300, or 10% of contributions or expenditures not reported, for first time offenders $600, or 15% of contributions or expenditures not reported, for second time offenders $1,200, or 20% of contributions or expenditures not reported, for third and subsequent offenses The full list of candidates and PACs not in compliance with the annual reporting requirement is available here.

Paul Manafort had plan to benefit Vladamir Putin government

President Donald Trump‘s former campaign chairman, Paul Manafort, secretly worked for a Russian billionaire to advance the interests of Russian President Vladimir Putin a decade ago and proposed an ambitious political strategy to undermine anti-Russian opposition across former Soviet republics, The Associated Press has learned. The work appears to contradict assertions by the Trump administration and Manafort himself that he never worked for Russian interests. Manafort proposed in a confidential strategy plan as early as June 2005 that he would influence politics, business dealings and news coverage inside the United States, Europe and the former Soviet republics to benefit the Putin government, even as U.S.-Russia relations under Republican President George W. Bush grew worse. Manafort pitched the plans to Russian aluminum magnate Oleg Deripaska, a close Putin ally with whom Manafort eventually signed a $10 million annual contract beginning in 2006, according to interviews with several people familiar with payments to Manafort and business records obtained by the AP. Manafort and Deripaska maintained a business relationship until at least 2009, according to one person familiar with the work. “We are now of the belief that this model can greatly benefit the Putin Government if employed at the correct levels with the appropriate commitment to success,” Manafort wrote in the 2005 memo to Deripaska. The effort, Manafort wrote, “will be offering a great service that can re-focus, both internally and externally, the policies of the Putin government.” Manafort’s plans were laid out in documents obtained by the AP that included strategy memoranda and records showing international wire transfers for millions of dollars. How much work Manafort performed under the contract was unclear. The disclosure comes as Trump campaign advisers are the subject of an FBI probe and two congressional investigations. Investigators are reviewing whether the Trump campaign and its associates coordinated with Moscow to meddle in the 2016 campaign. Manafort has dismissed the investigations as politically motivated and misguided, and said he never worked for Russian interests. The documents obtained by AP show Manafort’s ties to Russia were closer than previously revealed. In a statement to the AP, Manafort confirmed that he worked for Deripaska in various countries but said the work was being unfairly cast as “inappropriate or nefarious” as part of a “smear campaign.” “I worked with Oleg Deripaska almost a decade ago representing him on business and personal matters in countries where he had investments,” Manafort said. “My work for Mr. Deripaska did not involve representing Russia’s political interests.” Deripaska became one of Russia’s wealthiest men under Putin, buying assets abroad in ways widely perceived to benefit the Kremlin’s interests. U.S. diplomatic cables from 2006 described Deripaska as “among the 2-3 oligarchs Putin turns to on a regular basis” and “a more-or-less permanent fixture on Putin’s trips abroad.” In response to questions about Manafort’s consulting firm, a spokesman for Deripaska in 2008 — at least three years after they began working together — said Deripaska had never hired the firm. Another Deripaska spokesman in Moscow last week declined to answer AP’s questions. Manafort worked as Trump’s unpaid campaign chairman last year from March until August. Trump asked Manafort to resign after AP revealed that Manafort had orchestrated a covert Washington lobbying operation until 2014 on behalf of Ukraine’s ruling pro-Russian political party. The newly obtained business records link Manafort more directly to Putin’s interests in the region. According to those records and people with direct knowledge of Manafort’s work for Deripaska, Manafort made plans to open an office in Moscow, and at least some of Manafort’s work in Ukraine was directed by Deripaska, not local political interests there. The Moscow office never opened. Manafort has been a leading focus of the U.S. intelligence investigation of Trump’s associates and Russia, according to a U.S. official. The person spoke on condition of anonymity because details of the investigation were confidential. Meanwhile, federal criminal prosecutors became interested in Manafort’s activities years ago as part of a broad investigation to recover stolen Ukraine assets after the ouster of pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych there in early 2014. No U.S. criminal charges have ever been filed in the case. FBI Director James Comey, in confirming to Congress the federal intelligence investigation this week, declined to say whether Manafort was a target. Manafort’s name was mentioned 28 times during the hearing of the House Intelligence Committee, mostly about his work in Ukraine. No one mentioned Deripaska. White House spokesman Sean Spicer said Monday that Manafort “played a very limited role for a very limited amount of time” in the campaign, even though as Trump’s presidential campaign chairman he led it during the crucial run-up to the Republican National Convention. Manafort and his associates remain in Trump’s orbit. Manafort told a colleague this year that he continues to speak with Trump by telephone. Manafort’s former business partner in eastern Europe, Rick Gates, has been seen inside the White House on a number of occasions. Gates has since helped plan Trump’s inauguration and now runs a nonprofit organization, America First Policies, to back the White House agenda. Gates, whose name does not appear in the documents, told the AP that he joined Manafort’s firm in 2006 and was aware Manafort had a relationship with Deripaska, but he was not aware of the work described in the memos. Gates said his work was focused on domestic U.S. lobbying and political consulting in Ukraine at the time. He said he stopped working for Manafort’s firm in March 2016 when he joined Trump’s presidential campaign. Manafort told Deripaska in 2005 that he was pushing policies as part of his work in Ukraine “at the highest levels of the U.S. government — the White House, Capitol Hill and the State Department,” according to the documents. He also said he had hired a “leading international law firm with close ties to President Bush to support our client’s interests,” but he did not identify the firm. Manafort also said he was employing unidentified legal experts for the effort at leading universities and

Barack Obama signs short-term bill to fund government past election

President Barack Obama has signed a short-term funding bill to keep the government from shutting down at the end of the week. Lawmakers eager to leave town to campaign for re-election gave themselves breathing room by voting to continue existing spending levels for another 10 weeks, beyond the Nov. 8 election. Members of Congress will have to reach agreement on funding for the rest of the budget year when they meet in a lame-duck session after the election. The bill Obama signed Thursday also provides $1.1 billion to address the Zika crisis. And it has $500 million to help Louisiana flood victims. Republished with permission of the Associated Press.

Donald Trump campaign plans $140 million ad buy

Donald Trump‘s campaign is planning for what it says will amount to $140 million worth of advertising from now until Election Day. The total, if executed, would include $100 million in television airtime and $40 million in digital ads, according to senior communications adviser Jason Miller. The plan represents a new approach for the billionaire businessman, who has repeatedly bragged in recent weeks about how much less he’s spent than Democratic rival Hillary Clinton and seemed to rely heavily on free media coverage of his large rallies. Through this week, the Trump campaign has put only about $22 million into TV and radio ads for the general election, according to Kantar Media’s political advertising tracker. Clinton has spent more than five times as much on those kinds of ads, $124 million so far. Trump’s new ad buy will include 13 states, from key battlegrounds such as Florida, North Carolina, Ohio and Pennsylvania, to new targets of Maine, New Mexico and Wisconsin, Miller said. About $40 million of the ads will play on national TV, he said. That averages to about $16.7 million per week in TV ads; Miller said the first $15 million ad buy was made Friday, although media buyers and services such as Kantar Media didn’t immediately see evidence of that. Clinton’s ad reservations going forward total about $11 million per week, but her campaign can add to those buys at any time. Trump’s advertising plan costs more than his campaign has in the bank, meaning he needs to dip into his own pockets or continue raising major money. As of Sept. 1, the campaign had about $50 million in cash, though in a news release earlier this month, the campaign said it had $97 million in cash when including his joint accounts with Republican Party allies. Trump has continued to experience strong fundraising online this month, campaign aides said. Miller said upcoming national television ads would focus on Trump’s key campaign themes, such as the economy and law and order. The local ads, however, are expected to focus on ways Trump’s policies might benefit local communities and families, Miller said. Republished with permission of the Associated Press.

Gold cards and red hats: A Trumpian approach to fundraising

Donald Trump is underwriting his presidential bid by selling the Donald Trump lifestyle — and campaign finance records show it is working. For the low price of $25, you can snag a Trump Gold Card emblazoned with your name or join a campaign “Board of Directors” that comes with a personalized certificate. For $30, grab one of Trump’s signature red hats — billed as “the most popular product in America.” Supporters can elevate themselves to “big league” by ponying up $184 for a signed, “now out of print” copy of Trump’s book, “The Art of the Deal.” There’s a catch to some of these merchandising claims. There is no evidence the board of directors exists. “The Art of the Deal” is still in print, available for $9.34 in paperback. And the new campaign edition of the book is signed by an autopen, not Trump, as noted in the solicitation’s fine print. Regardless, the appeals have paid off. Through the end of July, people giving $200 or less made up about half of his campaign funds, according to fundraising reports through July. For Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton, those small gifts accounted for about 19 percent. The two candidates each claim over 2 million donors, but Trump has been fundraising in earnest for only about three months, compared to Clinton’s 17-month operation. Both are expected to report the details of their August fundraising to federal regulators on Tuesday. “His brand appeals to quite a number of people,” said John Thompson, digital fundraising director for Ted Cruz‘s Republican presidential campaign. “It’s smart for him to use it for fundraising. The celebrity factor builds a natural donor community on its own, without him having to do too much.” Hyperbolic campaign marketing is a natural fit for Trump, who has puffed up the value of what he sold throughout his business career. At times, Trump has offered golf memberships or Trump University seminars at a “discount” from an imaginary, inflated price; and he has declared condo projects close to selling out when in reality they were struggling. “You want to say it in the most positive way possible,” Trump once told attorneys who asked him whether he had ever lied about his properties to sell them. “I’m no different from a politician running for office.” Perhaps it is no surprise, then, that his campaign has adopted that same approach, outspending Clinton on campaign merchandise while running a brisk retail operation that helps him raise the money for, among other things, crucial get-out-the-vote efforts and advertising to spread his message. Trump’s appeals for smaller contributions are reminiscent of Bernie Sanders, whose signature line in the Democratic primary this year was that his campaign was paid for by $27 donations. Sanders’ digital fundraiser, Michael Whitney, questioned whether Trump’s small donor haul would continue since it does not appear the campaign has done much to get email addresses that could be turned into fresh batches of new potential donors. “This feels more like a battering ram than a well-thought-out digital program,” Whitney said. One of Trump’s most frequent fundraising offers has been a “gold card” that identifies the holder as an Executive Member for a “one-time induction fee.” “In the past, I have asked supporters for a one-time induction fee of $100. But because of your outstanding generosity to date, I am only asking you to make a $35 contribution,” the email asks. The Associated Press found no evidence of an online solicitation in which the card was sold for the undiscounted price of $100. The gold card offer is reminiscent of a Trump Visa card that became available in 2004. In a press release for it, Trump pitched it as “the best deal” and warned declining it “could get you fired.” Trump also seeks to make would-be donors feel like part of the campaign. Several emails have sought “campaign advice,” asked for help with debate preparation and even offered people the chance to join a campaign “board of directors.” There’s no evidence such a board exists, and the campaign did not respond to questions about it. But the gold card and executive board membership gimmicks are getting results, said Tom Sather, senior director of research at the email data solutions firm Return Path. The firm measures emails much the way Nielsen measures television viewership, by extrapolating from a large panel of study participants. Emails from the Trump campaign and Trump joint committees with the Republican Party have an average open rate of 11 percent, Sather said. The 10 gold card-related emails had a far higher open rate of 18 percent, and executive board emails had an open rate of 19 percent, he said. “These kinds of offers intrigue people and make them feel exclusive and special,” he said. Ever the marketer, Trump has also dominated the campaign swag front. In April, May and June, Trump spent about $3 million on merchandise that’s then sold to donors, an AP review of campaign finance reports found. Clinton’s operation spent about $2 million in the same time period. Republished with permission of the Associated Press.

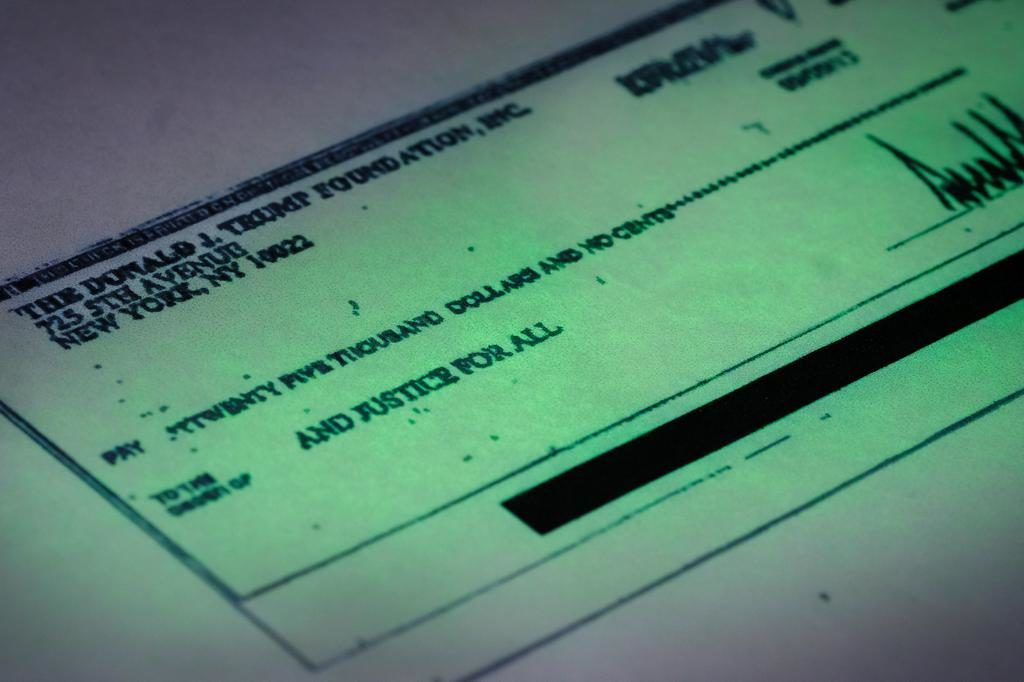

Donald Trump signed improper charity check supporting Florida AG Pam Bondi

Donald Trump‘s signature, an unmistakable if nearly illegible series of bold vertical flourishes, was scrawled on the improper $25,000 check sent from his personal foundation to a political committee supporting Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi. Charities are barred from engaging in political activities, and the Republican presidential nominee’s campaign has contended for weeks that the 2013 check from the Donald J. Trump Foundation was mistakenly issued following a series of clerical errors. Trump had intended to use personal funds to support Bondi’s re-election, his campaign said. So, why didn’t Trump catch the purported goof himself when he signed the foundation check? Trump lawyer Alan Garten offered new details about the transaction to The Associated Press on Thursday, after a copy of the Sept. 9, 2013, check was released by New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman. Garten said the billionaire businessman personally signs hundreds of checks a week, and that he simply didn’t catch the error. “He traditionally signs a lot of checks,” said Garten, who serves as in-house counsel for various business interests at Trump Tower in New York City. “It’s a way for him to monitor and keep control over what’s going on in the company. It’s just his way. … I’ve personally been in his office numerous times and seen a big stack of checks on his desk for him to sign.” The 2013 donation to Bondi’s political group has garnered intense scrutiny because her office was at the time fielding media questions about whether she would follow the lead of Schneiderman, who had then filed a lawsuit against Trump University and Trump Institute. Scores of former students say they were scammed by Trump’s namesake get-rich-quick seminars in real estate. Bondi, whom the AP reported in June personally solicited the $25,000 check from Trump, took no action. Both Bondi and Trump say their conversation had nothing to do with the Trump University litigation, though neither has answered questions about what they did discuss or provided the exact date the conversation occurred. House Democrats called earlier this week for a federal criminal investigation into the donation, suggesting Trump was trying to bribe Bondi with the charity check. Schneiderman, a Democrat, said he was already investigating to determine whether Trump’s charity broke state laws. Garten said the series of errors began after Trump instructed his staff to cut a $25,000 check to the political committee supporting Bondi, called And Justice for All. Someone in Trump’s accounting department then consulted a master list of charitable organizations maintained by the IRS and saw a Utah charity by the same name that provides legal aid to the poor. According to Garten, that person, whom he declined to identify by name, then independently decided that the check should come from the Trump Foundation account rather than Trump’s personal funds. The check was then printed and returned for Trump’s signature. After it was signed, Garten said, Trump’s office staff mailed the check to its intended recipient in Florida, rather than to the charity in Utah. Emails released by Bondi’s office show her staff was first contacted at the end of August by a reporter for The Orlando Sentinel asking about the Trump University lawsuit in New York. Trump’s Sept. 9 check is dated four days before the newspaper printed a story quoting Bondi’s spokeswoman saying her office was reviewing Schneiderman’s suit, but four days before the pro-Bondi political committee reports receiving the check in the mail. Compounding the confusion, the following year on its 2013 tax forms the Trump Foundation reported making a donation to a Kansas charity called Justice for All. Garten said that was another accounting error, rather than an attempt to obscure the improper donation to the political group. In March, The Washington Post first revealed that that the donation to the pro-Bondi group had been misreported on the Trump Foundation’s 2013 tax forms. The following day, records show Trump signed an IRS form disclosing the error and paying a $2,500 fine. Bondi has endorsed Trump’s presidential bid and has campaigned with him this year. She has said the timing of Trump’s donation was coincidental and that she wasn’t personally aware of the consumer complaints her office had received about Trump University and the Trump Institute, a separate Florida business that paid Trump a licensing fee and a cut of the profits to use his name and curriculum. Neither company was still offering seminars by the time Bondi took office in 2011, though dissatisfied former customers were still seeking promised refunds. Republished with permission of the Associated Press.

As Hillary Clinton asks for money, what she says remains a mystery

It was a very busy, very lucrative weekend for Hillary Clinton in the summer playground of the East Coast’s moneyed elite. She brunched with wealthy backers at a seaside estate in Nantucket, snacking on shrimp dumplings and crab cakes. A few hours later, she and her husband dined with an intimate party of thirty at a secluded Martha’s Vineyard estate. And on Sunday afternoon, she joined the singer Cher at an “LGBT summer celebration” on the far reaches of Cape Cod. By Sunday evening, Clinton had spoken to more than 2,200 campaign donors. But what she told the crowds remains a mystery. Clinton has refused to open her fundraisers to journalists, reversing nearly a decade of greater transparency in presidential campaigns and leaving the public guessing at what she’s saying to some of her most powerful supporters. It’s an approach that differs from the Democratic president she hopes to succeed. Since his 2008 campaign, President Barack Obama has allowed reporters traveling with him into the backyards and homes of wealthy donors to witness his some of his remarks. While reporters are escorted out of Obama’s events before the start of the juicier Q&A, the president’s approach offers at least a limited measure of accountability that some fear may disappear when Clinton or Republican nominee Donald Trump moves into the White House. “Unfortunately these things have a tendency to ratchet down,” said Larry Noble, the general counsel of the nonprofit Campaign Legal Center. “As the bar gets lower, it’s hard to raise it again.” Clinton’s campaign does release limited details about her events, naming the hosts, how many people attended and how much they gave. That’s more than Trump, whose far fewer fundraisers are held entirely away from the media, with no details provided. Even some Democrats privately acknowledge that Clinton’s penchant for secrecy is a liability, given voters continued doubts about her honesty. While Clinton will occasionally take questions from reporters at campaign stops, she has not held a full-fledged news conference in more than 260 days. Trump has held several. She refuses to release the transcripts of dozens of closed-door speeches she delivered to companies and business associations after leaving the State Department, despite significant bipartisan criticism. And since announcing her presidential bid in April 2015, Clinton has held around 300 fundraising events — only around five have been open to any kind of news coverage. “It does feed this rap about being secretive and being suspicious,” said GOP strategist Whit Ayers. Clinton’s aides have promised for weeks that greater access to her events will be coming soon. But Trump’s lack of disclosure has given her political cover to keep the doors closed, particularly as she conducts a period of intense fundraising before the final sprint to Election Day. While Clinton is expected to make only two public appearances before the end of August, she and her top backers will mingle with donors at no fewer than 54 events according to a fundraising schedule obtained by The Associated Press. Reporters covering these events wait outside, in vans, parking lots and vacant guesthouses — even at homes they’ve entered with Obama at previous events. In Provincetown on Sunday, five reporters crowded into the corner of a parking lot, clinging to a chain-link fence as they tried to catch Clinton’s speech to a crowd of about 1,000 supporters. None of her remarks seemed particularly remarkable: The candidate could faintly be heard running through her standard stump speech. During a Saturday fundraiser at a stately Martha’s Vineyard estate, faint cheers could be heard as Clinton addressed 700 donors on a green lawn overlooking the water. Staffers instructed drivers to roll up the windows of the vans where reporters waited before being ushered into a nearby guesthouse. What a candidate tells his or her rich donors has long been a subject of intense speculation in American politics, in part because the message can be different from what they offer to voters. Obama is still haunted by a comment he made at a 2008 fundraiser in San Francisco, calling voters in small town Pennsylvania “bitter” and saying they cling to “guns or religion.” He learned a lesson: At events during his 2012 campaign, staffers set up a table where guests were expected to check their cellphones before entering. Clinton has tried to ban tweeting, Instagram and other forms of social media at some of her events. Four years ago, a waiter recorded and leaked remarks GOP nominee Mitt Romney made about the “47 percent” of voters who are “dependent on government and would vote for Obama “no matter what” at a closed Florida fundraiser. After his convention, Romney started opening his fundraisers to the media to grab headlines, especially on days when he had no other public appearances. His former aides say that’s not a problem for Clinton. “Quite frankly, if I’m her, it may not be a bad thing to let Donald Trump be the only candidate making news on any given day,” said former Romney campaign aide Ryan Williams. “She can stay dark for five straight days and let Trump trip all over himself.” ___ Keep track of how much Clinton and Trump are spending on television advertising, and where they’re spending it, via AP’s interactive ad tracker http://elections.ap.org/content/ad-spending. Republished with permission of The Associated Press.

Republican donors deny Ted Cruz, John Kasich needed funds, data show

It seems like a logical pairing: Republican donors who despise Donald Trump, and two GOP presidential hopefuls sticking it out to keep him from the nomination. Yet such a financial cavalry never arrived for Ted Cruz and John Kasich, ignoring their impassioned pleas for financial help. Donors who gave as much as allowed by law to establishment darlings Jeb Bush or Marco Rubio have mostly disappeared from the political landscape, according to an Associated Press analysis of campaign finance records. Less than 3 percent of the nearly 14,600 donors who gave the $2,700 limit to Bush or Rubio have also ponied up the maximum amount to Kasich or Cruz. By not writing those checks, they’re depriving Cruz and Kasich of as much as $39 million each in their final push to topple Trump, who has formidably deep pockets and has loaned $36 million to his own campaign. Trump trounced his competitors in Tuesday’s elections, putting him in a stronger position to win the nomination outright in the next six weeks of voting. The quest to stop him has grown so dire that Cruz on Wednesday took the unusual step of announcing a running mate, Carly Fiorina. Earlier, he and Kasich agreed to divide up some remaining primary states to improve their chances of beating Trump. But donors’ continued shunning of Cruz and Kasich is one reason they haven’t had more success. “There are a significant number of major fundraisers in the Republican Party whose networks are exhausted and donors who are worn thin emotionally from the effort they made for a candidate who is no longer in the race,” said Wayne Berman, a longtime Republican fundraiser. “That combination has led to many, many people sitting on the sidelines.” He’s speaking from experience. Berman was the national finance chairman for Rubio and chose not to raise money for any other candidate after the Florida senator dropped out March 15. Both Kasich and Cruz have feverishly pitched themselves to donors as the candidate best able to unify the party. It has been a particularly tough fit for Cruz, a first-term Texas senator who has made his name as an unrelenting conservative fighter — even against those in his own party. He’s had a healthy core of his own donors, including roughly 3,900 who have given the maximum amount. In fact, Cruz is the best Republican campaign fundraiser of the 2016 cycle, and started April with $8.8 million cash on hand. Still, this critical stage of the race has called for extra outreach, particularly with expensive contests such as California coming up and Cruz in need of better primary performances to derail Trump. Cruz has stepped up his requests of donors who might not have otherwise considered him. He and his wife, a Goldman Sachs manager on leave, talked to New York financiers last week at the Harvard Club of New York City. They’re seldom responding, AP’s analysis shows. Through the end of March, just 186 Bush-Rubio maxed-out donors gave the maximum to Cruz. Fred Zeidman, a Houston-based fundraiser for Bush’s failed bid, is one of them. He said he felt he “owed” the donation to Cruz because of his strong support of Israel, Zeidman’s top issue. “I wanted to show him my appreciation for that,” Zeidman said. Still, Zeidman said he can understand why lots of former Bush and Rubio donors are reluctant. “At this point, many of them feel like the main objective should be to beat the Democratic nominee, so they’re keeping their powder dry until the general election, in effect just letting the primary system sort itself out,” he said. Kasich, the governor of Ohio, has attracted 174 maxed-out donors who also gave the maximum to Bush and Rubio. He’s won over some of the party’s top female donors, including Anna Mann, Rupert Murdoch’s ex-wife; Lynne Walton, a Wal-Mart heiress; and Helen DeVos, wife of Amway founder Richard DeVos. But Kasich has been in desperate need of more donors willing to give as much as they can. He started April with just $1.2 million cash on hand. The AP analysis is based on reports of campaign contributions filed with the Federal Election Commission from the beginning of the 2016 presidential election cycle through the end of March. The AP looked at donors who gave the maximum primary amount to Bush or Rubio with those who had given the maximum primary amount to the Democratic and Republican candidates still in the race, comparing each donor’s name, city, state and zip code. Because the analysis excluded donors if any of the information didn’t match, it could result in a slight undercount. The analysis revealed another troubling finding for Cruz and Kasich: Democratic front runner Hillary Clinton attracted about the same number of Bush-Rubio donors as did their campaigns. About a dozen Bush-Rubio donors have also given to Trump. A tiny core of 15 Bush-Rubio donors continued to hedge their bets by maxing out to both Cruz and Kasich — continuing their spread-the-love approach this election cycle. Stanley Hubbard, a billionaire Minnesota broadcast executive, has doled out checks of $2,500 or more to Scott Walker, Jeb Bush, Marco Rubio, Ben Carson, Carly Fiorina, Chris Christie and John Kasich. Of his multi-layered giving, Hubbard told the AP a few months ago that he wanted anyone other than Trump or Cruz at the top of the GOP ticket because he saw either of them as devastating for the party’s down-ballot prospects. Trump’s continued dominance led him to revise that view: He gave Cruz a check of $2,700 on March 31. “He’s not my first choice, no,” Hubbard said last week. He said he has no regrets about his heretofore fruitless campaign gifts. “Not a bit. When you give to politicians, sometimes you lose. That’s the way it works.” Republished with permission of the Associated Press.

John Mica defends use of campaign fund to pay for hundreds of meals

U.S. Rep. John Mica likes taking constituents out to lunch (or breakfast, dinner or coffee). And he loves having his re-election campaign pay for it. The latter preference has Mica, a 12-term Republican from Winter Park, explaining why his re-election campaigns are paying for scores of “meals with constituents” tallying tens of thousands of dollars a year in food and drink, when other members of Congress rarely, if ever, do so. The campaign picks up the check for Mica taking people to lunch in Washington, back home in Winter Park, and also in places far from either Florida’s Congressional District 7 or Mica’s office, such as restaurants in New York, Scottsdale, Ariz., and the Carolinas. In recent days, Democrats have been pushing opposition research highlighting these meal expenses, seeking to expose a chink in Mica’s re-election armor. News blogs in both Washington and Central Florida, including the influential TheHill.com, have picked up on the issue, exploring concerns raised by Democrats that Mica might be using his campaign fund as an unlimited resource for holding meal meetings with anyone, or no one, or how he could justify “constituent meals” in places like Arizona or New York. In an interview with FloridaPolitics.com, Mica not only refuted any allegations of wrongdoing, he argued that he handles such meals “more responsibly” than other members of Congress. Most members take such meals, but most typically use tax money, from official office expense accounts, rather than campaign money. Every meal involves meetings with constituents — residents or businesses from his district, Mica insisted. And every meal paid for by his campaign, he added, is one fewer meal paid for by taxpayers. “I think for 20 years we have not put constituent expenses on the tab of the taxpayer,” Mica said. Lately, he’s been doing it a lot. A FloridaPolitics.com review of Mica’s campaign expenses, as posted with the Federal Election Commission, finds he had such meals on 208 different occasions during the 2013-’14 election cycle, a campaign during which Mica didn’t even have a serious opponent. Mica’s re-election campaign spent $71,174 on those meals. In August 2014, Mica got 72 percent of the vote in a primary with three opponents. And in November 2014, he got 64 percent in the general election against two opponents including Democratic nominee Wes Newman, who quit campaigning and moved out of Florida in August. His meal numbers in that election were unusually high, even by Mica campaign standards. In the previous three election cycles — which Mica also won in landslides — he averaged about 100 such meals, totaling about $30,000, per campaign. Jermaine House, a spokesman for the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, accused Mica of using the campaign fund as a slush fund for meals with anyone, anytime. Mica’s 2014 election cycle meals included some high-ticket events, including a $1,475 charge one night at Buca Di Beppo in Maitland and a $1,448 dinner at Fleming’s in Winter Park. He met people for meals five times at the Winter Park Racquet Club, which is on his street, charging the campaign $2,359, and went to the 310 Park South Restaurant in Winter Park 10 times, charging $1,551. On the other hand, Mica also went to Panera Bread in Winter Park 10 times, for just $65 in charges. Most of the time, Mica said he has numerous guests, leading to high costs. Often, he said, the events are reciprocations for events others have held for him. “We usually try to hold those back in the district,” Mica said. “Every one of those is with somebody. I do so [on] many of those. Look at this. This is a three-day week,” he said of the current week. He then noted he had already hosted — and charged to his campaign — four meal-with-constituent meetings, including one with University of Central Florida students and their families, who had come to Washington for the American Israel Public Affairs Committee conference. Another was for Orange County Mayor Teresa Jacobs and others who testified before his committee about heroin. The 2014 meal in New York involved a time when Mica and Central Florida traffic planners were all in New York for a conference; he took them out to lunch, his campaign said. Multiple meals in South and North Carolina were organized around Mica’s family summer home. The Arizona meal involved a Delta Chi convention, which included Mica and other Central Floridians. For 2016, Mica again faces no major opponents, though Democrats have been recruiting hard, because with the most recent redistricting, CD 7 is now pretty close to evenly balanced between Democrats and Republicans. In 2015, he charged 58 meals, totaling $12,600. Mica’s extensive use of campaign money for constituent meal meetings is highly unusual. FloridaPolitics.com checked the 2013-14 campaign expenses of 17 other members of Congress from Florida; none had expensed even one constituent meal using campaign finances. On the other hand, it is not unusual for other members of Congress to charge such meals to their office expenses. Annual totals of $10,000 and up are commonplace. Last year, Mica said, he spent $73 on constituent meals from his office fund.“It’s such a unique case. I’ve never run into this before,” said “It’s such a unique case. I’ve never run into this before,” said Joshua Stewart, spokesman for the Sunlight Foundation, a nonprofit group that monitors campaign finance and Congressional spending. Under the law, Stewart said, a member of Congress could opt to put the meals on either the office account or the campaign account, but almost all put it on the office account, reflecting such meetings as official business, rather than re-election business. “This is not an ideal way for a member of Congress to be conducting communications with constituents,” Stewart noted. Why not? Campaigns keep detailed records of every meal with constituents, Mica replied, and show everyone who was there, and why they got together. The Central Floridians who come to his out-of-town constituent meals are not all ordinary voters. Among the names of attendees provided to FloridaPolitics were lobbyists and Republican fundraisers such as Rusty Roberts, Jim Huckeba, Leila Nodarse and the late Fred Leonhardt. Mica suggested those