Joe Guzzardi: Clock ticking on Alejandro Mayorkas; House files impeachment articles

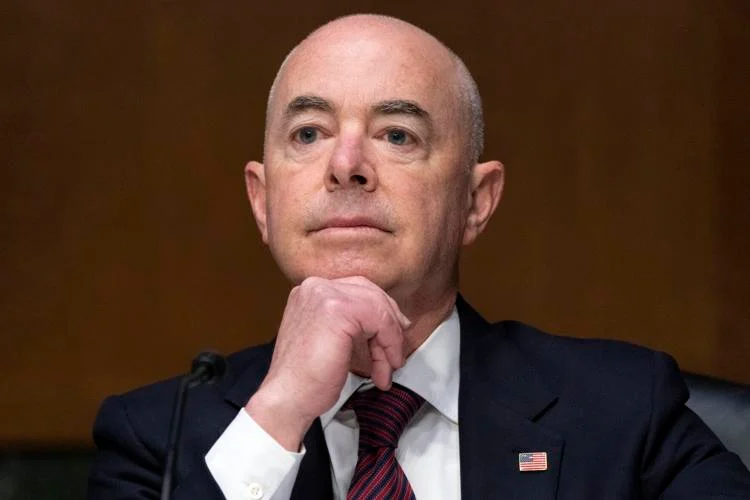

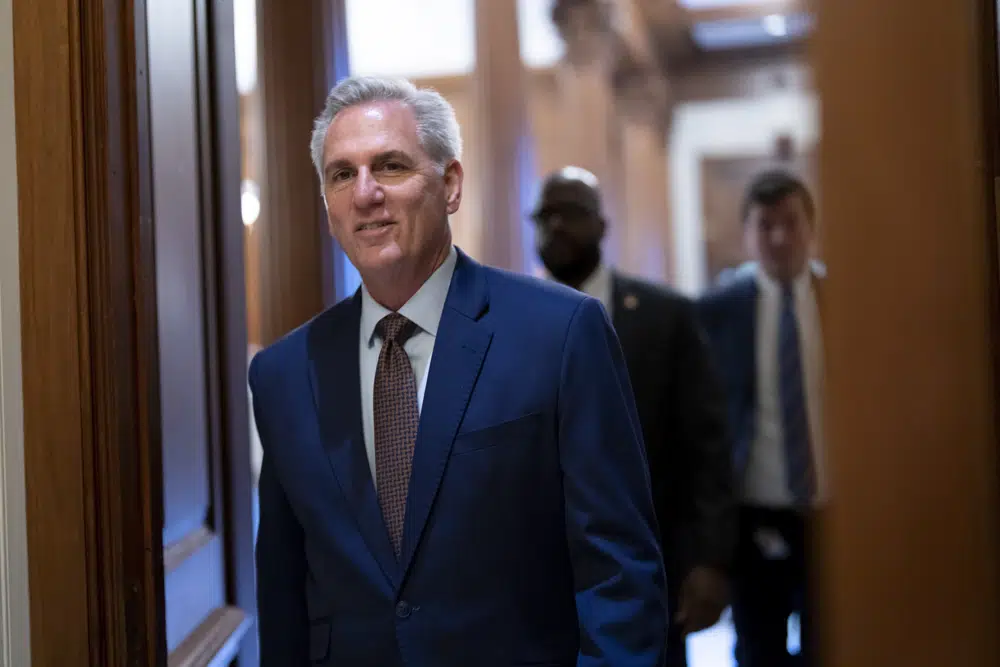

The 118th Congress had barely convened before the Senate’s amnesty addicts traveled to the border and began pontificating about the bipartisan immigration action they were about to embark upon. Whenever Congress touts bipartisanship as it relates to immigration, the sub rosa message is that amnesty legislation, which Americans have consistently rejected, is percolating. Neither amnesty’s failed history – countless futile efforts since the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act – nor the Republican-controlled House of Representatives stopped determined Senators Kyrsten Sinema (I-Ariz.), Mark Kelly, (D-Ariz.), Thom Tillis (R-N.C.), John Cornyn (R-Texas), Chris Murphy (D-Conn.), James Lankford (R-Okla.) and Jerry Moran (R-Kan.). Tillis tipped off the group’s hand when he said, “It’s not just about border security; it’s not just about a path to citizenship or some certainty for a population.” One of those populations would be the “Dreamers,” with a 20-year-long failed legislative record. Sinema took advantage of the border trip to promote her failed amnesty, her leftovers from the December Lame Duck session, a three-week period when radical immigration legislation usually finds a home. Sen. Chris Coons (D-Del.) tweeted that “our immigration system is badly broken…” drivel that’s been repeated so often it’s lost whatever meaning it once may have had. The immigration system is “badly broken,” to quote Coons, because immigration laws have been ignored for decades. Critics laughingly call the out-of-touch, border-visiting senators the “Sell-Out Safari.” Coons’ tweet is classic duplicity. Coons, Sinema, Kelly, and Murphy have consistently voted against measures to enforce border security and against fortifying the interior by providing more agents and by giving more authority to Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Republicans Tillis and Cornyn are also immigration expansionists. Tillis worked with Sinema on her unsuccessful Lame Duck amnesty. Cornyn sponsored, with Sinema and Tillis as cosponsors, the “Bipartisan Border Solutions” bill that would have built more processing centers to expedite migrants’ release and to create a “fairer and more efficient” way to decide asylum cases. The bill, which never got off the ground, would have rolled out the red carpet to more prospective migrants at a time when the border is under siege. The good news is that the border safari, an updated version of the 2013 Gang of Eight that promoted but couldn’t deliver an amnesty, was a cheap photo op that intended to reflect concern about the border crisis when, in fact, the senators’ voting records prove that the invasion doesn’t trouble them in the least. More good news is that Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.), the new Speaker of the House, represents enforcement proponents’ best chance to move their agenda forward since 2007 when Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) first held the job. Republicans John Boehner (R-Ohio) and Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) followed Pelosi from 2011 to 2019 when Pelosi returned as Speaker. Although Boehner and Ryan are Republicans, their commitment to higher immigration levels was not much different than Pelosi’s. Boehner and Ryan received 0 percent scores on immigration, meaning that they favor looser immigration enforcement and more employment-based visas for foreign-born workers. Also in McCarthy’s favor is the public support for tightening the border. Polls taken in September 2022 showed that a majority of Americans, including 76 percent of Republicans and 55 percent of Independents, thought President Joe Biden should be doing more to ensure border security. Moreover, a plurality of Americans opposes using tax dollars to transport migrants, a common practice in the Biden catch-and-release era. McCarthy must become more proactive and make good on his November call for the secretary of the Department of Homeland Security to resign or face impeachment. “He cannot and must not remain in that position,” McCarthy said. “If Secretary [Alejandro] Mayorkas does not resign, House Republicans will investigate every order, every action, and every failure to determine whether we can begin an impeachment inquiry.” McCarthy has the backing of the Chairmen of the Judiciary and Oversight Committees, Jim Jordan and James Comer. On January 9, Pat Fallon (R-Texas) filed articles of impeachment that charged Mayorkas with, among other offenses, “high crimes and misdemeanors.” Mayorkas insists he won’t resign and that he’s prepared for whatever investigations may come his way. Assuming the House presses on, and that the DHS secretary remains committed to keeping his post, Capitol Hill fireworks are assured, the fallout from which could lead to Mayorkas’ departure. Joe Guzzardi is a nationally syndicated newspaper columnist who writes about immigration and related social issues. Joe joined Progressives for Immigration Reform in 2018 as an analyst after a ten-year career directing media relations for Californians for Population Stabilization, where he also was a Senior Writing Fellow. A native Californian, Joe now lives in Pennsylvania. Contact him at jguzzardi@pfirdc.org.

Kevin McCarthy makes big gains for speaker, but still falls short

Republican leader Kevin McCarthy flipped 15 colleagues to support him in dramatic votes for House speaker on Friday, making extraordinary gains on the fourth day and the 12th and 13th ballots of a grueling standoff that was testing American democracy and the Republicans’ ability to govern. The changed votes from conservative holdouts, including the chairman of the chamber’s Freedom Caucus, put McCarthy closer to seizing the gavel for the new Congress — but not yet able. The stunning turnaround came after McCarthy agreed to many of the detractors’ demands — including the reinstatement of a longstanding House rule that would allow any single member to call a vote to oust him from office. That change and others mean the job he has fought so hard to gain will be weakened. After McCarthy won the most votes for the first time on the 12th ballot, a 13th was swiftly launched, this time just between McCarthy and the Democratic leader, with no nominated Republican challenger to siphon GOP votes away. But six GOP holdouts still cast their ballots for unnominated others, denying him the majority needed. The showdown that has stymied the new Congress came against the backdrop of the second anniversary of the January 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol, which shook the country when a mob of then-President Donald Trump’s supporters tried to stop Congress from certifying the Republican’s 2020 election defeat to Democrat Joe Biden. A few minutes before voting began in the House chamber, Republicans tiring of the spectacle walked out when one of McCarthy’s most ardent challengers railed against the GOP leader. “We do not trust Mr. McCarthy with power,” said Republican Matt Gaetz of Florida as colleagues streamed out of the chamber in protest of his remarks. Contours of a deal with conservative holdouts who have been blocking McCarthy’s rise emerged, but an agreement had seemed still out of reach after three dismal days and 11 failed votes in a political spectacle unseen in a century. But an upbeat McCarthy told reporters as he arrived at the Capitol Friday morning, “We’re going to make progress. We’re going to shock you.” One significant former holdout, Republican Scott Perry, chairman of the conservative Freedom Caucus, tweeted after his switched vote for McCarthy: “We’re at a turning point.” But several holdouts remained. The final 12th vote tally: McCarthy, 213 votes; Democrat Hakeem Jeffries 211. Other Republicans Jim Jordan and Kevin Hern picked up protest votes. With 431 members voting, McCarthy was still a few votes short of a majority. When Rep. Mike Garcia nominated McCarthy for a 12th time, he also thanked the U.S. Capitol Police who were given a standing ovation for protecting lawmakers and the legislative seat of democracy on January 6. The agreement McCarthy presented to the holdouts from the Freedom Caucus and others centers around rules changes they have been seeking for months. Those changes would shrink the power of the speaker’s office and give rank-and-file lawmakers more influence in drafting and passing legislation. Even if McCarthy is able to secure the votes he needs, he will emerge as a weakened speaker, having given away some powers, leaving him constantly under threat of being voted out by his detractors. But he would also be potentially emboldened as a survivor of one of the more brutal fights for the gavel in U.S. history. At the core of the emerging deal is the reinstatement of a House rule that would allow a single lawmaker to make a motion to “vacate the chair,” essentially calling a vote to oust the speaker. McCarthy had resisted allowing a return to the longstanding rule that former Speaker Nancy Pelosi had done away with, because it had been held over the head of past Republican Speaker John Boehner, chasing him to early retirement. But it appears he had no other choice. The chairman of the chamber’s Freedom Caucus, Scott Perry of Pennsylvania, who had been a leader in Trump’s efforts to challenge his presidential election loss to Democrat Joe Biden, appeared receptive to the proposed package, tweeting an adage from Ronald Reagan, “Trust but verify.” Other wins for the holdouts include provisions in the proposed deal to expand the number of seats available on the House Rules Committee, to mandate 72 hours for bills to be posted before votes, and to promise to try for a constitutional amendment that would impose federal limits on the number of terms a person could serve in the House and Senate. Lest hopes get ahead of reality, conservative holdout Ralph Norman of South Carolina said: “This is round one.” It could be the makings of a deal to end a standoff that has left the House unable to fully function. Members have not been sworn in, and almost no other business can happen. A memo sent out by the House’s chief administrative officer Thursday evening said that committees “shall only carry out core Constitutional responsibilities.” Payroll cannot be processed if the House isn’t functioning by January 13. After a long week of failed votes, Thursday’s tally was dismal: McCarthy lost seventh, eighth, and then historic ninth, 10th, and 11th rounds of voting, surpassing the number from 100 years ago in the last drawn-out fight to choose a speaker. The California Republican exited the chamber and quipped about the moment: “Apparently, I like to make history.” Feelings of boredom, desperation, and annoyance seemed increasingly evident. Democrats said it was time to get serious. “This sacred House of Representatives needs a leader,” said Democrat Joe Neguse of Colorado, nominating his own party’s leader, Hakeem Jeffries, as speaker. What started as a political novelty, the first time since 1923 a nominee had not won the gavel on the first vote, has devolved into a bitter Republican Party feud and deepening potential crisis. Democratic leader Jeffries of New York won the most votes on every ballot but also remained short of a majority. McCarthy ran second, gaining no ground. Pressure has grown with each passing day for McCarthy to somehow find the votes he needs or

Robert Aderholt plans to vote for Kevin McCarthy for Speaker

In the November midterms, the voters gave Republicans a small majority in the U.S. House of Representatives. The new GOP House majority should select the next Speaker of the House after four years of Nancy Pelosi. The squabbling Republicans, however apparently can’t agree on who will get to be the new Speaker. On Monday, Congressman Robert Aderholt announced that he plans to vote for Rep. Kevin McCarthy to be the next Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives. “I’m planning to cast my vote for Kevin McCarthy to be the next Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives,” Aderholt said in a statement emailed to Alabama Today. “He’s earned it. No one has worked harder to take back the House than Kevin McCarthy.” “The American people elected a Republican majority in the House because they were tired of the direction of our nation and the leadership of Speaker Pelosi,” Aderholt continued. “The American people are expecting us to work to stop inflation, deal with the crisis at our southern border and hold the Biden Administration accountable. The sooner we elect a Republican Speaker, the sooner we can start.” As of press time, it was still in doubt if McCarthy could gather enough support to be elected Speaker. McCarthy did predict that Tuesday would be “a good day” when asked by reporters what he thought would happen in the Speaker’s vote. Ultra-conservatives previously opposed McCarthy in his previous bid for Speaker replacing former Speaker John Boehner. The House Caucus instead chose former Vice Presidential candidate Rep. Paul Ryan. Ryan did not run again in 2018 after disagreements with then-President Donald Trump. Club for Growth is reportedly urging members to oppose McCarthy’s bid for Speaker. Aderholt is the senior member of the Alabama congressional delegation. He has represented Alabama’s Fourth Congressional District since his election in 1996. Aderholt was the ranking member of the House Appropriations Committee during the last Congress. There are 222 Republicans in the 118th Congress to 212 Democrats. The vote for the next Speaker of the House is on Tuesday. To connect with the author of this story, or to comment, email brandonmreporter@gmail.com.

Kevin McCarthy’s race for speaker risks upending House on Day One

In his quest to rise to House speaker, Kevin McCarthy is charging straight into history — potentially becoming the first nominee in 100 years unable to win the job on a first-round floor vote. The increasingly real prospect of a messy fight over the speaker’s gavel on Day One of the new Congress on Jan. 3 is worrying House Republicans, who are bracing for the spectacle. They have been meeting endlessly in private at the Capitol, trying to resolve the standoff. Taking hold of a perilously slim 222-seat Republican majority in the 435-member House and facing a handful of defectors, McCarthy is working furiously to reach the 218-vote threshold typically needed to become speaker. “The fear is that if we stumble out of the gate,” said Rep. Jim Banks, R-Ind., a McCarthy ally, then the voters who sent the Republicans to Washington “will revolt over that and they will feel let down.” Not since the disputed election of 1923 has a candidate for House speaker faced the public scrutiny of convening a new session of Congress only to have it descend into political chaos, with one vote after another, until a new speaker is chosen. At that time, it eventually took a grueling nine ballots to secure the gavel. McCarthy, a Republican from Bakersfield, California, who was first elected in 2006 and who remains allied with Donald Trump, has signaled he is willing to go as long as it takes in a floor vote to secure the speaker’s job he has wanted for years. The former president has endorsed McCarthy and is said to be making calls on McCarthy’s behalf. McCarthy has given no indication he would step aside, as he did in 2015 when it was clear he did not have the support. But McCarthy also is acknowledging the holdouts won’t budge. “It’s all in jeopardy,” McCarthy said Friday in an interview with conservative Hugh Hewitt. The dilemma reflects not just McCarthy’s uncertain stature among his peers but also the shifting political norms in Congress as party leaders who once wielded immense power — the names of Cannon, Rayburn, and now Pelosi adorn House meeting rooms and office buildings — are seeing it slip away in the 21st century. Rank-and-file lawmakers have become political stars on their own terms, able to shape their brands on social media and raise their own money for campaigns. House members are less reliant than they once were on the party leaders to dole out favors in exchange for support. The test for McCarthy, if he is able to shore up the votes on Jan. 3 or in the days that follow, will be whether he emerges a weakened speaker, forced to pay an enormous price for the gavel, or whether the potentially brutal power struggle emboldens his new leadership. “Does he want to go down as the first speaker candidate in 100 years to go to the floor and have to essentially, you know, give up?” said Jeffrey A. Jenkins, a professor at the University of Southern California and co-author of “Fighting for the Speakership.” “But if he pulls this rabbit out of the hat, you know, maybe he actually has more of the right stuff.” Republicans met in private this past week for another lengthy session as McCarthy’s detractors, largely a handful of conservative stalwarts from the Freedom Caucus, demand changes to House rules that would diminish the power of the speaker’s office. The Freedom Caucus members and others want assurances they will be able to help draft legislation from the ground up and have opportunities to amend bills during the floor debates. They want enforcement of the 72-hour rule that requires bills to be presented for review before voting. Outgoing Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., and the past two Republican speakers, John Boehner and Paul Ryan, faced similar challenges, but they were able to rely on the currency of their position to hand out favors, negotiate deals, and otherwise win over opponents to keep them in line — for a time. Boehner and Ryan ended up retiring early. But the central demand by McCarthy’s opponents’ could go too far: They want to reinstate a House rule that allows any single lawmaker to file a motion to “vacate the chair,” essentially allowing a floor vote to boot the speaker from office. The early leaders of the Freedom Caucus, under BC, the former North Carolina congressman turned Trump’s chief of staff, wielded the little-used procedure as a threat over Boehner and later, over Ryan. It wasn’t until Pelosi seized the gavel the second time, in 2019, that House Democrats voted to do away with the rule and require a majority vote of the caucus to mount a floor vote challenge to the speaker. Rep. Chip Roy, R-Texas, said the 200-year-old rule was good enough for Thomas Jefferson, so it’s one he would like to see in place. “We’re still a long way from fixing this institution the way it needs to be fixed,” Roy told reporters Thursday at the Capitol. What’s unclear for McCarthy is even if he gives in to the various demands being made by the conservatives, whether that will be enough for them to drop their opposition to his leadership. Several House Republicans said they do not believe McCarthy will ever be able to overcome the detractors. “I don’t believe he’s going to get to 218 votes,” said Rep. Bob Good, R-Va., among the holdouts. “And so I look forward to when that recognition sets in and, for the good of the country, for the good of the Congress, he steps aside, and we can consider other candidates.” The opposition to McCarthy has promoted a counteroffensive from other groups of House Republicans who are becoming more vocal in their support of the GOP leader — and more concerned about the fallout if the start of the new Congress descends into an internal party fight. Rep. David Joyce, R-Ohio, who leads the Republican Governance Group, was wearing an “O.K.” button on his lapel — meaning, “Only Kevin,” he explained. Some have

In virus talks, Nancy Pelosi holds firm; Steven Mnuchin wants a deal

There are limits, and legal pitfalls, in trying to make an end run around the legislative branch.

The end of an era? Tea party class of House Republicans fades

The Republican newcomers stunned Washington back in 2010 when they seized the House majority with bold promises to cut taxes and spending and to roll back what many viewed as Barack Obama’s presidential overreach. But don’t call them tea party Republicans any more. Eight years later, the House Tea Party Caucus is long gone. So, too, are almost half the 87 new House Republicans elected in the biggest GOP wave since the 1920s. Some, including current Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and White House budget director Mick Mulvaney, joined the executive branch. Others slipped back to private life. Several are senators. Now, with control of the House again at stake this fall and just three dozen of them seeking re-election, the tea party revolt shows the limits of riding a campaign wave into the reality of governing. Rep. Austin Scott, R-Ga., who was president of that freshman class, objects to the tea party brand that he says was slapped on the group by the media and the Obama administration. It’s a label some lawmakers now would rather forget. “We weren’t who you all said we were,” Scott said. He prefers to call it the class of “small-business owners” or those who wanted to “stop the growth of the federal government.” Despite all those yellow “Don’t Tread on Me” flags and anti-Obama health law rallies, Scott said the new Republican lawmakers wanted to work with the president, if only Obama would have engaged them. “We didn’t come to take over the country,” he said. Yet change Washington they did, with a hard-charging, often unruly governing style that bucked convention, toppled GOP leaders and in many ways set the stage for the rise of Donald Trump. By some measures, the tea party Republicans have been successful. The “Pledge to America,” a 21-page manifesto drafted by House Republican leadership, outlined the promises. Among them: “stop out of control spending,” ″reform Congress” and “end economic uncertainty.” They forced Congress into making drastic spending cuts, in part by threatening to default on the nation’s debt, turning a once-routine vote to raise the U.S. borrowing limit into a cudgel during the annual budget fights. Republicans halted environmental, consumer and workplace protection rules, and that rollback continues today. Perhaps most notably, the GOP majority passed $1.5 trillion in tax cuts that Trump signed into law, delivering on the tea party slogan penned on so many protest signs: “Taxed Enough Already.” But former Rep. Tim Huelskamp, R-Kan., said the “most egregious failure” was the GOP’s inability to undo the Affordable Care Act, Obama’s signature domestic achievement. Huelskamp said the class never really stuck together. When he arrived that first week in Washington in January 2011, he was stunned to find the leadership slate already set with then-Rep. John Boehner, R-Ohio, as speaker-in-waiting, facing little resistance. “That was a sign: The establishment in Washington was happy to have our votes, but not to follow our agenda,” said Huelskamp, who lost a primary election in 2016 to a political newcomer and now runs the conservative Heartland Institute. It was “just a clear misunderstanding of what the people wanted.” Over time, budget deals were struck with Democrats, boosting spending back to almost what it was before the revolt. Combined with the tax package, the GOP-led Congress is on track to push annual deficits near $1 trillion next year, as high as during the early years of the Obama administration when the government struggled with a deep recession. Maya MacGuineas, president at the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, said Republicans talked a good game promising to balance the budget, but with control of Congress — and now the White House — they failed to tackle the tough tax-and-spending challenges needed to get there. “That’s a whole lot of talk and zero follow through,” she said. Other proposals to improve transparency in government — a pledge to “read the bill” and post legislation three days before votes — remain works in progress. House bills are typically made public, but sometimes just before midnight to conform with the three-day rule. Frustrations within the ranks grew, and the new class splintered. Not all of them had been favorites of their local tea party groups. Some joined other conservatives to form the House Freedom Caucus, which nudged Boehner to early retirement in 2015. Former Florida Rep. Allen West, among the more prominent class members who lost re-election and is now a Fox News contributor living in Texas, said the challenge for House Republicans heading into the fall election is, “Who are they? What do they stand for?” House Republicans are wrestling with a midterm message at a pivotal moment for a party that Boehner says no longer exists. “There is no Republican Party. There’s Trump’s party,” Boehner said at a recent policy conference in Michigan. Boehner’s successor as speaker, Rep. Paul Ryan, R-Wis., also is stepping aside. He was a conservative up-and-comer long before the tea party, but has run into many of the same challenges Boehner faced in managing a fractured majority. He will retire after this term. In fact, there are an unusually high number of House Republicans retiring this year, including nearly a dozen from the tea party class. Several are running to be governors or senators, though some have already lost in primaries. Others, including Rep. Trey Gowdy, R-S.C., another rising star, are simply moving on. Some resigned this year amid ethics scandals. Jenny Beth Martin, a co-founder of Tea Party Patriots, says every movement “goes through phases.” As the group looks to elect the next “Tea Party 100″ members of the House, it’s seeking “tested and proven” candidates beyond the “citizen legislators” who powered the early days. Another 2010 leader, South Carolina’s Tim Scott, now a senator, says he has no problem with the tea party label that’s now etched in history. But he reminds his colleagues as they campaign that to keep the majority they must also eventually govern and that “promises made should be promises kept.” Republished

Paul Ryan vents frustration over GOP infighting over immigration

A frustrated Speaker Paul Ryan chided House Republicans for election-season infighting over immigration that sank the party’s farm bill last week, participants in a closed-door meeting said Tuesday. Leaders said they will schedule a late- June showdown over immigration, an issue that has divided the GOP for years. “I think he said ‘gee whiz’ and ‘gosh’ and used the word ‘crap’ once,” Rep. Mark Amodei, R-Nev., said of Ryan’s remarks to his colleagues. “For Paul Ryan, ‘crap’ is pretty blue language.” At a news conference minutes later, the Wisconsin Republican criticized anew an effort by GOP moderates to force votes on immigration by collecting signatures from a majority of House members on a little-used procedure called a discharge petition. The centrists need just five more GOP signatures to prevail. “I can guarantee you a discharge petition will not make law,” Ryan said. That was a reference to the expectation that the votes moderates want to have would produce a bill that President Donald Trump would consider too weak and veto. Ryan also defended himself against calls from conservatives that he step down as speaker in the wake of the party’s anarchy over the farm bill and continuing disarray on immigration. Ryan will retire from the House after this year but has said he will remain as speaker until he leaves office. “Members drafted me into this job because of who I am and what I stand for,” he said. He was elected speaker in 2015 after conservatives pressured his predecessor, John Boehner, R-Ohio, to step aside. Asked if he would remain as speaker all year, he said, “Obviously I serve at the pleasure of the members.” He said Republicans should concentrate on the party’s legislative agenda and not have “a divisive leadership election.” Lawmakers exiting the GOP meeting said leaders told them the House would vote on immigration during the third week of June. They said it was unclear exactly what they would vote on. The centrist push for immigration votes is considered likely to result in passage of a middle-ground measure backed by a handful of Republicans and all Democrats. Ryan has said he will avert that outcome, though it’s unclear how, and many conservatives consider it intolerable. Conservative and moderate GOP leaders negotiated privately Monday over ways to win centrist support for a conservative-backed measure that for months has floundered short of the 218 Republican votes it would need for House passage. They discussed changes that would help young “Dreamer” immigrants brought to the U.S. illegally as children and immigrant farm workers stay longer in the U.S., said one lawmaker who described the private discussions on condition of anonymity. The conservative bill would currently reduce legal immigration, clear the way for construction of President Donald Trump’s border wall with Mexico and let Dreamers stay in the U.S. for renewable three-year periods. All Democrats oppose the measure and it would have no chance of clearing the more moderate Senate. The farm bill crashed last Friday, partly because of opposition by members of the hard-right House Freedom Caucus. They had refused a leadership offer for a vote on the conservative immigration bill in June, which they said was too late. Some members of the Freedom Caucus suggested it would be time for Ryan to step down should moderates prevail. “If we run an amnesty bill out of a Republican House, I think all options are on the table,” said Rep. Scott Perry, R-Pa., a member of the group, when asked if Ryan should remain as speaker if the moderates’ effort succeeds. Many conservatives say legislation protecting immigrants in the U.S. illegally from deportation is amnesty. Other Republicans said it seemed unlikely Ryan would abandon his post. They said potential successors including Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., so far lack the GOP votes they’d need to win the job. The moderates need 218 signatures — a House majority — on a petition to force votes on immigration bills. With all 193 Democrats expected to sign, the moderates need five more than the 20 signatures they already have. If they succeed, a vote could occur no earlier than late June. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Kevin McCarthy and Steve Scalise are likely contenders for House speaker

Some say it’s a fight between West and South. Or who might win an endorsement from President Donald Trump. Or a test of who can woo conservatives. But one thing is clear: If the showdown between California Rep. Kevin McCarthy and Louisiana Rep. Steve Scalise for House speaker is a popularity contest, it will be tight. “Steve is the more low-key guy, Kevin is more the big handshake, but they’re equally popular,” said Rep. Peter King, R-N.Y. “It’s not like right versus left or a good guy versus a bad guy.” House Speaker Paul Ryan told colleagues Wednesday he wouldn’t seek re-election in November, implicitly starting the race to replace him. Disconcertingly for the GOP, Trump’s unpopularity and early Democratic momentum leave it unclear whether Ryan’s replacement will be speaker or minority leader. For now, McCarthy and Scalise are seen as the chief contenders. McCarthy, 53, an affable Californian, is his party’s No. 2 House leader and was one of the earliest and steadiest backers of Trump’s presidential campaign. If Trump weighs into the contest, his clout could rally lawmakers behind his favored candidate, though it could alienate others who want a leader who has their back, not necessarily the president’s. It’s uncertain whether Trump will intervene or who he’d support. McCarthy was elected in 2006 and rocketed into a leadership job in 2009, thanks to his campaigning for fellow Republicans. He replaced Eric Cantor as majority leader in 2014 after the Virginian unexpectedly lost a primary for his House seat and quit. In 2015, McCarthy sought to succeed Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, who’d alienated conservatives who considered him insufficiently doctrinaire. McCarthy abruptly left that contest days later after failing to line up enough votes, and Ryan accepted the post. Scalise, 52, the House GOP vote counter and No. 3 leader, was first elected a decade ago and had little national name recognition until tragedy thrust him into headlines. He was shot at a congressional baseball practice last year and is still recovering from his injuries, an ordeal that’s earned the conservative former state legislator broad respect. “The strength he’s shown with his injury, I think, has heightened where he is” among colleagues, said Rep. Phil Roe, R-Tenn. Lawmakers and GOP donors want a leader who can raise money, and there McCarthy has an advantage. He raised $8.75 million in the first quarter of this year and has done fundraisers for 40 GOP candidates, said a person familiar with his political operation. Scalise has raised $3 million, a record for House whips, and hosted almost 50 events, his aides said. Neither man is known for rhetorical flourishes, with McCarthy in particular prone to sentences that defy the rules of grammar. And both have resume problems that fellow Republicans insisted they’d overcome. In 2014, Scalise was discovered to have addressed a white-supremacist group in 2002 founded by former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke. Scalise apologized and said he’d been unaware of the group’s racial views. McCarthy suggested in 2015 that a House committee probing the deadly 2012 raid on the U.S. embassy in Benghazi, Libya, had damaged Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton’s poll numbers, undermining GOP arguments that the investigation wasn’t politically motivated. That raised questions about his ability as a communicator, a key for party leaders. But he was one of Trump’s earliest and most loyal congressional supporters in the 2016 presidential race. Some Republicans prefer Scalise’s deep red state background to McCarthy’s bright blue California, since the GOP’s chief strongholds are in rural and red state districts. “You have a lot of the Southern states who are looking to shift leadership back to that part of the country,” said Rep. Steve Russell, R-Okla. Scalise is viewed as more conservative than McCarthy, important in a House GOP conference that’s drifted to the right. That could be intensified after November, when Republicans are expected to lose seats and many of those departing will be moderates. Conservative groups have awarded Scalise modestly stronger voting ratings than McCarthy. But McCarthy has worked to improve his relationship with conservatives, including trying to craft legislation cutting spending from the government budget enacted recently. Either man could cut a deal with the House Freedom Caucus. Those roughly 30 conservative members could theoretically deliver their votes to a contender in exchange for a promise to back a caucus member for a leadership post. Rep. Mark Meadows, R-N.C., who heads the Freedom Caucus, said a candidate’s willingness to listen to all lawmakers is “probably the top priority” for backing someone. Neither Scalise nor McCarthy would acknowledge a race for Ryan’s job or definitively deny it. Scalise said it’s not “time to talk about what titles people want,” while McCarthy said, “There is no leadership election. Paul is speaker.” Those close to Scalise say he is unlikely to directly challenge McCarthy. But he doesn’t need to. By offering himself as an alternative choice, ready in case McCarthy fails to muster support, he is essentially making an indirect bid for the top post. Congressional leadership races often move quickly, with candidates rushing to win supporters and outmaneuver rivals. Several lawmakers said privately such moves are underway. But others said the race could stretch until after the election clarifies the number, ideology and mood of House Republicans. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Paul Ryan’s retirement sending ripples of uncertainty through GOP

House Speaker Paul Ryan’s abrupt announcement that he will retire rather than seek another term in Congress as the steady if reluctant wingman for President Donald Trump sent new ripples of uncertainty through a Washington already on edge and a Republican Party bracing for a rough election year. The Wisconsin Republican cast the decision to end his 20-year career as a personal one — he doesn’t want his children growing up with a “weekend dad” — but it will create a vacuum at both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue. It will leave congressional Republicans without a measured voice to talk Trump away from what some see as damaging impulses, and it will rob Trump of an influential steward to shepherd his more ambitious ideas into legislation. It’s unusual for a House speaker, third in line to succeed the president, to turn himself into a lame duck, especially so for Ryan, a once-rising GOP star who is only 48 and was the party’s vice presidential candidate in 2012. His decision fueled fresh doubts about the party’s ability to fend off a Democratic wave, fed by opposition to Trump, in November. And it threw the House into a leadership battle that could end up pushing Ryan aside sooner than he intended and crush any hopes for significant legislation before the election. Ryan, though, said he had no regrets after having accomplished “a heckuva lot” during his time in a job he never really wanted. He said fellow Republicans have plenty of achievements to run on this fall, including the tax cuts Congress delivered, which have been his personal cause and the centerpiece of his small-government agenda, even though they helped skyrocket projected annual deficits toward $1 trillion. “I have given this job everything I have,” Ryan said Wednesday. Speculation over Ryan’s future had been swirling for months, but as he dialed up colleagues and spoke by phone with Trump, the news stunned even top allies. Ryan announced his plans at a closed-door meeting of House Republicans. Rep. Mark Walker of North Carolina said an emotional Ryan “choked up a few times trying to get through” his remarks and received three standing ovations. He later briefly thanked Trump in public for giving him the chance to move GOP ideas ahead. While Ryan was crucial in getting the tax cuts passed, a prime Trump goal, he and the president have had a difficult relationship. Trump showed impatience with Congress’ pace in dealing with his proposals, and Ryan had to deal with a president who shared little of his interest in policy detail. Still, for many Republicans, it’s unclear who will be left in leadership to counterbalance Trump. Ryan has been “a steady force in contrast to the president’s more mercurial tone,” said Rep. Mark Sanford of South Carolina. “That’s needed.” The speaker had been heading toward this decision since late last year, said a person familiar with his thinking, but as recently as February he had considered running for another term. His own father died suddenly of a heart attack when he was 16, and though Ryan is in good health, the distance from his family weighed on him. A final decision was made over the two-week congressional recess, which he partly spent on a family vacation in the Czech Republic. Ryan, from Janesville, Wisconsin, was first elected to Congress in 1998. Along with Reps. Eric Cantor and Kevin McCarthy, he branded himself a rising “Young Gun” in an aging party, a new breed of hard-charging Republican ready to shrink the size of government. He was GOP presidential nominee Mitt Romney’s running mate in 2012. Ryan was pulled into the leadership job by the sudden retirement in 2015 of Speaker John Boehner, who had struggled to control the chamber’s restless conservative wing. He has had more trust with the hardliners in the House. “That’s probably his greatest gift to us,” said Rep. Kevin Cramer of North Dakota. “His ability to bridge the vast divide.” House Majority Leader McCarthy, a Californian known to be tighter with Trump, is expected to again seek the top leadership post that slipped from his reach in 2015. He will likely compete with Majority Whip Steve Scalise of Louisiana. Ryan’s announcement came as Republicans are bracing for a potential blue wave of voter enthusiasm for Democrats, who need to flip at least 24 GOP-held seats in November to regain the majority. As the House GOP’s top fundraiser, Ryan’s lame-duck status could send shockwaves through donor circles that are relying on his leadership at the helm of the House majority. He has hauled in $54 million so far this election cycle. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, who has worked with Ryan, praised his colleague’s tenure. The Democratic House leader, Nancy Pelosi of California, said she hoped Ryan would work constructively on bipartisan goals before he leaves. In Wisconsin, Republicans had no obvious successor in waiting. The most likely GOP candidate for Ryan’s seat is state Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, Republicans in the state said. Another Republican mentioned as a potential candidate is longtime Ryan family friend and backer Bryan Steil, an attorney and member of the University of Wisconsin Board of Regents. Democrat Randy Bryce, a colorful ironworker who has cultivated an “IronStache” moniker, had been Ryan’s best-known challenger, drawing liberal support from around the country. Janesville teacher Cathy Myers has also been running on the Democratic side. The only declared Republicans are Paul Nehlen, who was banned from Twitter earlier this year for posts criticized as racist or anti-Semitic, and Nick Polce, an Army veteran who also co-owns a security consulting firm. While his plans are uncertain once he steps down in January, Ryan has long said being speaker would be his last job in elected office. Others have suggested that an ideal job for the policy wonk could be running a think tank, noting the leader of the conservative American Enterprise Institute recently announced he would be stepping down. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

What’s next for Paul Ryan?

Paul Ryan’s future as House speaker has been such a topic of speculation that even the simple question of whether he will seek re-election to his Wisconsin seat remains secret. Officially, Ryan says he’s still deciding. But a person familiar with Ryan’s thinking told The Associated Press this week the speaker plans to file campaign paperwork and intends to win his seat. To do so, the Republican would have to fend off primary challengers, including one styled after President Donald Trump, and Democrats are fired up about a union ironworker, Randy Bryce, who goes by the Twitter moniker “Iron Stache.” If Ryan emerges victorious, even those closest to him aren’t certain he’ll stay in Congress, particularly if Republicans lose their House majority. Asked whether Ryan would serve in the minority, the person who discussed his re-election plans with AP would not say. The person was not authorized to discuss Ryan’s plans and spoke on condition of anonymity. Ryan’s political spokesman Jeremy Adler said Thursday, “The speaker speaks for himself on this topic, and there is no update to his last public comments.” Washington has been guessing about Ryan’s next step for months, with reports rising to a minor frenzy as allies seek to dispel any notion of a lame-duck speaker, which would be damaging both to fundraising efforts and to governing. Some Republicans speculate that Ryan’s work in Congress is complete now that he’s accomplished his career goal of ushering tax cuts into law. Even if Republicans keep control of the House, it’s doubtful he could achieve much more as speaker, a job he never wanted in the first place, especially with an unreliable partner in Trump. It’s even harder, they say, to envision him as minority leader. Charlie Sykes, an author and longtime ally who had a falling out with Ryan over the GOP’s embrace of Trump, is among those betting the speaker moves on. “I can’t imagine him wanting to stick around too long,” said Sykes, who pinned Ryan’s dilemma on a president who “undermines and distracts” from the GOP’s agenda. “This has been the story of the last two years — him trying to push this policy agenda amid the storm of distractions from the president.” Others expect Ryan still has sizable goals he’d like to accomplish, including downsizing the welfare system and other safety net programs, as he outlined in an impassioned monologue to reporters after the tax bill last year. And as much as Ryan fancies himself a policy wonk who prefers the realm of ideas, he’s actually become increasingly skilled at the art of politics. Unlike his predecessor, Speaker John Boehner, who was forced into early retirement by the House’s rebellious right flank, Ryan has been able to persuade the conservative Freedom Caucus and others from open revolt. If he wants another term as speaker or leader, Ryan may well be able to secure the votes to win it. “He’s an eternal optimist,” said Luke Hilgemann, former head of the Koch-backed Americans for Prosperity, who now runs GOP campaigns in Wisconsin and other states. “He believes the job isn’t done yet.” And so the debate rolls on. After one report late last year suggesting Ryan’s 2018 campaign would be his last, Trump called the speaker to let him know he would be disappointed if that were true. The speaker assured the president he had no plans to leave, according to those familiar with the call. Just this week, a Republican congressman, Mark Amodei of Nevada, mused openly to home-state reporters of “rumors” the speaker would not only retire from Congress, but that the No. 3 Republican, Rep. Steve Scalise of Lousiana, was on deck to replace him as speaker. It caused a mini-uproar nationally, and overwhelmed the Reno news site. Later, Amodei said he had no regrets about publicly sharing the chatter from Congress. But he also acknowledged he had no firsthand knowledge of Ryan’s thinking. “He’s got to say, ’I want to be the speaker in the 116th Congress,” Amodei told AP, referring to the session after the election. “I haven’t heard, ’I want to be the speaker of the House.” Ryan has allowed questions to linger in part because he keeps his inner circle of confidantes close and doesn’t always fully commit to staying on the job, which he reluctantly took in 2015 after Boehner retired. At the time, the next-in-line Republican, Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy of California, withdrew from the race when it appeared he did not have enough support. It’s now a jump ball if McCarthy or Scalise would win the speaker’s job if Ryan were to step aside. Both are popular with House Republicans, but they also have limitations. McCarthy is not seen as conservative enough by some hard-liners and Scalise is still recovering from life-threatening wounds after being shot at congressional baseball practice last year. Neither is openly jockeying to take on Ryan. Ryan has shown few obvious signs of a desire to quit, raising $44 million and visiting 30 states in 2017, much of the money for the House GOP’s campaign committee. The filing deadline in Wisconsin is in June. A Ryan political aide said that talking about the House GOP’s record and ensuring candidates have enough resources to run remain Ryan’s “top priorities.” Asked earlier this year if he would stay on as speaker if Republicans retain the majority, Ryan left room for debate. “Am I going to be speaker? Yes, if we keep the majority, then the Republican speaker,” he said in January on CBS’ Face the nation. “You’re asking me if I’m going to run for re-election? That’s a decision my wife and I always make each and every term when we have filing in Wisconsin late in spring. And I haven’t — I’m not going to share my thinking with you before I even talk to my wife.” Pressed, he said: “I have no plans of going anywhere anytime soon.” Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Joe Henderson: No surprise Ted Cruz chose not to play it safe

The safe play for Ted Cruz would have been to simply give Donald Trump a less-than-tepid endorsement as the Republican standard bearer for president. Party bosses and worker bees alike would have praised him for uniting Republicans in their holy war against Hillary Clinton. Even more, Cruz would have been ideally positioned to be the GOP’s choice in 2020 if, as looks more likely every day after this chaotic Republican convention, Trump gets thumped in November. But Cruz wouldn’t do it. He wouldn’t say it. Are you surprised? I’m not. If we know anything about the U.S. Senator from Texas, it’s that he doesn’t care if you don’t like him. He uses your loathing as reinforcement that you are part of the problem and must be fixed. His unwillingness to work with even his own party has made him a pariah to many. Former House Speaker John Boehner called him “Lucifer in the flesh.” He has made a career out of grandstand plays and attacking members fellow Republicans (I use that term loosely) for not being ideologically pure. You think he cares? I think he loves annoying the crap out of people. And you could just see his diabolical mind working when, for reasons passing understanding, GOP bosses gave Cruz prime-time real estate to speak his mind Wednesday night. He was warmly welcomed at first – the last holdout coming into the fold and all that — and returned that love by giving a tremendous speech. He laid out his conservative chops so decisively that about halfway through I almost expected those in the arena to demand a recount so they could pick him instead of Trump. It built to a crescendo as he told everyone watching not to stay at home in November. Yeah. Here it comes. The moment we’ve all been waiting for. “Vote for ….” Yes? Your conscience! Wow! He got booed out of the arena. Afterward, billionaire Sheldon Adelson wouldn’t let Cruz into the GOP donor suite. Security had to escort Cruz’s wife, Heidi, out of sight, lest she become a target for baffled and agitated delegates. Well, let us not forget that along with being devious and devilish, Cruz is vengeful. Trump tried to smear Heidi Cruz on her appearance during the campaign. He even suggested Cruz’s father might have had a clandestine role in John Kennedy’s assassination. So, you betcha! There was some prime-time payback due and Cruz delivered a sucker punch that only added to the image of a convention that has not just gone off the rails, but is now careening down the canyon toward the rocks below. Cruz is telegraphing to the deep conservative base, which he owns but Trump needs, that even four years of Hillary is worth it if it means he can rescue them in 2020. And just to add one more euphemistically upraised middle finger to the party, Cruz’s speech far overshadowed the coming out party of vice presidential nominee … oh, what’s his name? Well, Cruz has done it now. The implosion of the Republican Party as we know it is nearing completion. Going forward, if the GOP excommunicates him, it wouldn’t surprise me a bit if Cruz didn’t try to shepherd his ultra conservatives into a third party of constitutional purists. The man loves chaos. It’s all because he couldn’t, wouldn’t, and convinced himself he shouldn’t say three words: “Vote for Trump.” The words Cruz wouldn’t say spoke loudest of all. ___ Joe Henderson has had a 45-year career in newspapers, including the last nearly 42 years at The Tampa Tribune. He has covered a large variety of things, primarily in sports but also hard news. The two intertwined in the decade-long search to bring Major League Baseball to the area. Henderson was also City Hall reporter for two years and covered all sides of the sales tax issue that ultimately led to the construction of Raymond James Stadium. He served as a full-time sports columnist for about 10 years before moving to the metro news columnist for the last 4 ½ years. Henderson has numerous local, state and national writing awards. He has been married to his wife, Elaine, for nearly 35 years and has two grown sons — Ben and Patrick.

Wisconsin-based ‘Cheesehead Revolution’ challenged by Donald Trump

A trio of Wisconsin Republicans looking to inject the party with their own youthful, aggressive brand of conservatism ushered in the “Cheesehead Revolution.” Their aim was to position the GOP for success in the 2016 presidential election. Then came Donald Trump. With the anti-Trump movement in full swing even as Trump solidifies his front-runner status in the presidential race, the focus turns to the April 5 primary in the home state of those three heavyweights: House Speaker Paul Ryan, Republican National Committee Chairman Reince Priebus and Gov. Scott Walker. They are trying to chart a course in the face of a revolt over Trump’s rise and what it means for the future of the Republican Party — and for each of them individually. “The great plans came off the tracks with the presence of Donald Trump, both in terms of where the party would be and presidential ambitions,” said Democratic Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett, who ran against Walker twice and lost both times. “Donald Trump changed everything.” The “Cheesehead Revolution,” as Walker and Priebus dubbed it, began in 2011. With Ryan rising in the House, Walker a new governor, and Priebus taking over the party apparatus, the trio then represented what looked to be a unified party in a swing state that could become a GOP stronghold in presidential races to come. But in 2012, Mitt Romney lost to incumbent Barack Obama, with Ryan as his running mate. Priebus tried to steer the party in a more inclusive direction. In 2013, he issued the “Growth and Opportunity Project,” aimed toward an immigration overhaul and outreach to minorities, and driven by the recognition that Hispanics in particular were rising as a proportion of the population. Now that tract is known as an autopsy report. The recommendations put Priebus at odds with more conservative Republicans. And now, two of the three remaining presidential candidates, Trump and Texas Sen. Ted Cruz, have built their campaigns not on trying to broaden the party by reaching out to Hispanics and minorities, but by appealing to evangelicals and more conservative white voters. Priebus’s report “has been haunting the Republican Party” ever since its release, said Steve King, an Iowa Republican congressman who backs Cruz. “It’s awfully hard to recover from something like that,” King said. Trump launched his campaign by calling Mexican immigrants rapists and criminals. He’s made a border wall a cornerstone of his platform. Those positions have torn at the party’s core, contributing to efforts to stop him. Priebus puts the best face on the chaotic campaign. He says his party is large enough to handle a variety of opinions about the best course. He cites record fundraising and voter turnout. He calls it a “miracle turnaround.” Ryan became House speaker in October, replacing John Boehner, and his stock has risen to a point that some Republicans see him as an alternative to Trump if the nomination isn’t settled going into the summer convention. “Paul Ryan has brought about climate change there,” said King, meaning the climate in Congress, “and I mean that in a very complimentary way.” King is one of the most conservative members of Congress and was a critic of Boehner. Just as he refused initial calls to run for speaker, Ryan has tried to tamp down talk of being drafted as an alternative to Trump at the convention. Robin Vos, the Republican speaker of Wisconsin’s state Assembly, said Trump’s rise has helped to put the Republican Party at a crossroads. But Vos said he still believes Walker, Ryan and Priebus are in positions to “change the face of government.” Vos pointed to Walker’s record as governor as proof that with a “good, articulate leader,” Republicans can advance their conservative agenda, even in a politically divided state like Wisconsin. Vos endorsed Cruz on Friday. But Walker has been struggling with public support since his failed presidential run. His call in September for other Republican candidates to join him and drop out of the race to make it easier for others to take on Trump went ignored for months. Walker still hasn’t endorsed anyone in the race, with Wisconsin’s primary just over a week away. He told AP he sees Trump’s popularity as an “an anomaly” that is overshadowed in significance by Republican success in governor’s races and state legislative contests for years. “You look over the last five, six years, the story that’s had the longer impact is not who the nominee is for one presidential election but this shift that’s happened nationally,” Walker said. Barrett, the Milwaukee mayor who lost to Walker in 2010 and 2012, said the political landscape has changed for Walker and Republicans since the governor won a recall election four years ago over his battle with public-service unions in the states. “A lot of the glitter’s gone,” he said. Republished with permission of the Associated Press.