Joe Biden talks gun control, extremism with New Zealand’s PM Jacinda Ardern

President Joe Biden praised New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern on Tuesday for her success in curbing domestic extremism and guns as he tries to persuade a reluctant Congress to tighten gun laws in the aftermath of horrific mass shootings in Uvalde, Texas, and Buffalo, New York. The long-planned talks between Biden and Ardern centered on trade, climate, and security in the Indo-Pacific, but the two leaders’ starkly different experiences in pushing for gun control loomed large in the conversation. Ardern successfully won passage of gun control measures in her country after a white supremacist gunman killed 51 Muslim worshippers at two Christchurch mosques in 2019. Less than a month later, all but one of the country’s 120 lawmakers voted in favor of banning military-style semiautomatic weapons. Biden told reporters at the start of his meeting with Ardern that he “will meet with the Congress on guns, I promise you,” but the White House has acknowledged that winning new gun legislation will be an uphill climb in an evenly divided Congress. The U.S. president praised Ardern for her “galvanizing leadership” on New Zealand’s efforts to curb the spread of extremism online and said he wanted to hear more about the conversations in her country about the issue. White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said the two leaders spent part of the meeting discussing “what has been done on gun reform” under Ardern’s watch. Ardern and French President Emmanuel Macron in 2019 launched an effort to work with tech companies on eliminating terrorist and violent extremist content online. Then-President Donald Trump declined to join the effort, but the Biden administration has since joined the Christchurch Call to Action. Biden over the weekend traveled to Uvalde, Texas, to grieve with a community that he said made clear to him they want to see Washington tighten gun laws in the aftermath of the shooting rampage that killed 19 children and two teachers. Biden heard similar calls for an overhaul of the nation’s gun laws earlier this month when he met with families of 10 Black people who were killed in a racist attack at a Buffalo supermarket. Biden and Ardern also discussed a May 15 shooting at a lunch banquet at a Taiwanese church in Laguna Woods, California that killed one person and wounded five others. “The pain is palpable,” said Biden, recalling his anguished conversations Sunday with families of victims of the Texas elementary school shooting. Ardern offered condolences and said she stood ready to share “anything that we can share that would be of any value” from New Zealand’s experience. “Our experience demonstrated our need for gun reform, but it also demonstrated what I think is an international issue around violent extremism and terrorism online,” Ardern told reporters following her more than hour-long meeting with Biden. “That is an area where we see absolutely partnership that we can continue to work on those issues.” It’s unclear what, if anything, from New Zealand could be applicable to the United States, which hasn’t passed a major federal gun control measure since soon after the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Connecticut that left 26 dead. A bipartisan group of senators held a private virtual meeting Tuesday to try to strike a compromise over gun safety legislation, but expectations remain low. Senators aren’t expected to even broach ideas for an assault weapon ban or other restrictions that could be popular with the public as ways to curb the most lethal mass shootings. Republican Sen. John Cornyn of Texas, who led the session alongside Sens. Chris Murphy, D-Conn., Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz., and Thom Tillis, R-N.C., called Tuesday’s talks a “very constructive conversation.” Meanwhile, House Judiciary Committee Jerrold Nadler plans to hold a hearing Thursday on the “Protecting our Kids Act” — a package of eight bills that has almost no hopes of passing the Senate but would serve as a marker in the debate. It includes calls to raise the age limits on semi-automatic rifle purchases from 18 to 21 years old; create a grant program to buy back large-capacity magazines; establish voluntary safe practices for firearms storage, and build on executive measures to ban bump stock devices and so-called ghost guns made from 3-D printing. Ardern, in comments to reporters, said the two countries’ political systems are “very different.” Speaking of the Christchurch shooting, she said that “in the aftermath of that, the New Zealand public had an expectation that if we knew what the problem was, that we do something about it. We had the ability with actually the near-unanimous support of parliamentarians to place a ban on semiautomatic military-style weapons and assault rifles and so we did that. But the New Zealand public set the expectations first and foremost.” The New Zealand prime minister did not urge any particular course of action to Biden during their talks but expressed a broad understanding of what the United States is going through, according to a senior Biden administration official who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the private conversation. Ardern last week, during a speech at Harvard University’s commencement, spoke to the scourge of disinformation that is spread and amplified on social media. She said it represents a threat to fragile democracies. The Christchurch gunman was radicalized online. The attack, like the Buffalo supermarket rampage, was live-streamed on social media, she noted. “The time has come for social media companies and other online providers to recognize their power and act on it,” she said at Harvard. Biden’s talks with Ardern came after he made his first visit to Asia last week, a trip to Japan and South Korea meant to highlight his administration’s efforts to put greater focus on the Indo-Pacific. In Japan, Biden launched the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, a new trade pact forged with 14 Pacific allies, including New Zealand. The U.S. sees the pact as an alternative to the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which moved forward without the U.S. after Trump pulled out. Ardern said she reiterated her commitment to TPP even as New Zealand has joined the new U.S.-launched Indo-Pacific

Experts raise alarm over ‘fiscal state of the union’ ahead of Joe Biden’s speech

President Joe Biden is expected to deliver the State of the Union address Tuesday evening, and economic and fiscal policy experts are raising the alarm about the fiscal state of the nation. The National Association for Business Economics (NABE) released its economic growth projections for the next quarter and downgraded their forecasts. “NABE panelists have downgraded their forecasts for economic growth in 2022,” the report said. “The median forecast for inflation-adjusted gross domestic product (real GDP) growth from the fourth quarter (Q4) 2021 to Q4 2022 is 2.9% – down from the 3.6% forecasted in the December 2021 Outlook Survey. In general, panelists anticipate further deceleration in GDP growth in 2023: the median forecast calls for GDP growth of 2.3%.” The report said experts point to policy “missteps” as a key factor. “Thirty percent of panelists identify monetary policy missteps as the greatest downside risk,” the report said. “One-quarter (25%) sees ongoing supply-chain issues and 19% cite geopolitical tensions/global growth slowdown as the most prominent downside risks to their growth projection (considering both probability of occurrence and potential impact).” Experts point to the soaring national debt and inflation as key reasons for the economic woes. Federal inflation data released Friday showed another significant increase in prices, the latest in a steady trend of inflation figures that have economists worried. The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) released data on Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE), a key marker of inflation, which has shown a sharp rise in recent months. “The PCE price index for January increased 6.1 percent from one year ago, reflecting increases in both goods and services …” BEA said. “Energy prices increased 25.9 percent while food prices increased 6.7 percent. Excluding food and energy, the PCE price index for January increased 5.2 percent from one year ago.” That increase was the highest in nearly four decades. A coalition of groups have come together to support a congressional resolution to require an annual “Fiscal State of the Union” to be released by certain federal agencies. “This concurrent resolution requires the congressional budget committees to conduct an annual joint hearing to receive a presentation from the Comptroller General regarding (1) the Government Accountability Office’s audit of the financial statement of the executive branch, and (2) the financial position and condition of the federal government,” said the official summary of the resolution, sponsored by Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz., in the Senate and Rep. Kathleen Rice, D-N.Y., in the House. The House has approved the measure, but the companion resolution in the Senate is still in committee. “Lawmakers need to begin paying more attention to our fiscal outlook,” said Maya MacGuineas, president of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. “An Annual hearing by the Senate and House Budget Committees featuring the Comptroller General would shine some much-needed light on our unsustainable budget situation, rather than sweeping it under the carpet.” The groups emphasized Republicans and Democrats are responsible for the national debt, which recently surpassed $30 trillion. The national debt has increased significantly under both Democratic and Republican administrations over the past two decades. “Both parties in Congress need to get serious about America’s debt and deficits, and it starts with a full, honest, and public accounting of the country’s financial health,” said Andrew Lautz, director of federal policy for National Taxpayers Union. “The Fiscal State of the Nation resolution is a first sensible step in understanding the federal government’s budget picture from year to year.” Republished with the permission of The Center Square.

Joe Biden hails infrastructure win as ‘monumental step forward’

President Joe Biden on Saturday hailed Congress’ passage of his $1 trillion infrastructure package as a “monumental step forward for the nation” after fractious fellow Democrats resolved a months-long standoff in their ranks to seal the deal. “Finally, infrastructure week,” a beaming Biden told reporters. “I’m so happy to say that: infrastructure week.” The House passed the measure 228-206 late Friday, prompting prolonged cheers from the relieved Democratic side of the chamber. Thirteen Republicans, mostly moderates, supported the legislation, while six of Democrats’ farthest left members opposed it. Approval of the bill, which promises to create legions of jobs and improve broadband, water supplies, and other public works, sends it to the desk of a president whose approval ratings have dropped and whose nervous party got a cold shoulder from voters in this past week’s off-year elections. Democratic candidates for governor were defeated in Virginia and squeaked through in New Jersey, two blue-leaning states. Those setbacks made party leaders — and moderates and liberals alike — impatient to produce impactful legislation and demonstrate they know how to govern. Democrats can ill afford to seem in disarray a year before midterm elections that could give Republicans congressional control. Voters “want us to deliver,” Biden said, and Friday’s vote “proved we can.” “On one big item, we delivered,” he added. The infrastructure package is a historic investment by any measure, one that Biden compares in its breadth to the building of the interstate highway system in the last century or the transcontinental railroad the century before. He called it a “blue-collar blueprint to rebuilding America.” His reference to infrastructure week was a jab at his predecessor, Donald Trump, whose White House declared several times that “infrastructure week” had arrived, only for nothing to happen. Simply freeing up the infrastructure measure for final congressional approval was like a burst of adrenaline for Democrats. Yet despite the win, Democrats endured a setback when they postponed a vote on a second, even larger bill until later this month. That 10-year, $1.85 trillion measure bolstering health, family, and climate change programs was sidetracked after moderates demanded a cost estimate on the measure from the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office. The postponement dashed hopes that the day would produce a double-barreled win for Biden with passage of both bills. But in an evening breakthrough brokered by Biden and House leaders, five moderates agreed to back that bill if the budget office’s estimates are consistent with preliminary numbers that White House and congressional tax analysts have provided. The agreement, in which lawmakers promised to vote on the social and environment bill by the week of Nov. 15, was a significant step toward a House vote that could ultimately ship it to the Senate. Elated by the bill’s passage, Biden held forth with reporters for over a half-hour Saturday morning, joking that his chances of getting the bill done had been written off multiple times, only for him to be able to salvage it. He said he would wait to hold a signing ceremony until lawmakers — Democrats and Republicans who voted for it — return to Washington after a week’s recess. The president acknowledged uncertainty surrounding his larger social and environmental spending package, saying “time will tell” whether he can keep popular provisions like universal paid family leave in the final version. He wouldn’t say whether he has private assurances from moderate Democrats in the House and Senate to pass the nearly $2 trillion bill, but said he was “confident” he would get the votes. Biden predicted Americans would begin to feel the impact of the infrastructure bill “probably starting within the next two to three months as we get shovels in the ground.” But the full impact will probably take decades to be fully realized. He added that he would visit some ports that would benefit from the legislation in the next week, as his administration tries frantically to ease supply chain disruptions that are raising prices on consumer goods before the holidays. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg said there’s a pent-up demand to get going on public works. He told CNN he’s already got $10 billion worth of applications for a certain program that’s only got $1 billion in it. “This is not just a short-term stimulus bill.” Biden said the investment would be viewed in 50 years as “When America decided to win the competition of the 21st century” with a rising China. The president and first lady Jill Biden delayed plans to travel Friday evening to their house in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware. Instead, Biden spoke to House leaders, moderates, and progressives. Rep. Pramila Jayapal, D-Wash., leader of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, said Biden even called her mother in India, though it was unclear why. “This was not to bribe me — this is when it was all done,” Jayapal told reporters. The lawmaker said her mother told her she “just kept screaming like a little girl.” In a statement, five moderates said that if the fiscal estimates on the social and environment bill raise problems, “we remain committed to working to resolve any discrepancies” to pass it. In exchange, liberals agreed to back the infrastructure measure, which they’d spent months holding hostage in an effort to press moderates to back the larger bill. The day marked a rare detente between Democrats’ moderate and liberal wings that party leaders hope will continue. The rival factions had spent weeks accusing each other of jeopardizing Biden’s and the party’s success by overplaying their hands. But Friday night, Jayapal suggested they would work together moving forward. Democrats have struggled for months to take advantage of their control of the White House and Congress by advancing their priorities. That’s been hard, in part because of Democrats’ slender majorities and bitter internal divisions. “Welcome to my world,” House Speaker Nancy Pelosi told reporters. “We are not a lockstep party.” Democrats’ day turned tumultuous early after a half-dozen moderates demanded the budget office’s cost estimate of the sprawling package of health, education, family, and climate change

Senate Dems push new voting bill, and again hit GOP wall

If at first you don’t succeed, make Republicans vote again. That’s the strategy Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer appears to be pursuing as the New York Democrat forced another test vote Wednesday on legislation to overhaul the nation’s election laws. For the fourth time since June, Republicans blocked it. Democrats entered the year with unified, albeit narrow, control of Washington, and a desire to counteract a wave of restrictive new voting laws in Republican-led states, many of which were inspired by Donald Trump’s false claims of a stolen 2020 election. But their initial optimism has given way to a grinding series of doomed votes that are meant to highlight Republican opposition but have done little to advance a cause that is a top priority for the party ahead of the 2022 midterm elections. The Senate voted against debating voting legislation Wednesday, with Republicans this time filibustering an update to the landmark Voting Rights Act, a pillar of civil rights legislation from the 1960s. GOP senators oppose the Democratic voting bills as a “power grab.” “This is a low, low point in the history of this body,” Schumer said after the failed vote, later adding, “The Senate is better than this.” The stalemate is forcing a reckoning among Senate Democrats about whether to make changes to the filibuster rule, which requires 60 votes for legislation to advance. That could allow them to muscle legislation through but would almost certainly come back to bite them if and when Republicans take back control of the chamber. Earlier Wednesday, Schumer met with a group of centrist Democrats, including Sens. Jon Tester of Montana, Angus King of Maine, and Tim Kaine of Virginia, for a “family discussion” about steps that could be taken to maneuver around Republicans. That’s according to a senior aide who requested anonymity to discuss private deliberations. But it’s also a move opposed by moderate Sens. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona and Joe Manchin of West Virginia. Without their support, Democrats won’t have the votes needed to make a change. Time is ticking down. Redistricting of congressional districts (a once-in-a-decade process Democrats want to overhaul to make less partisan) is already underway. And the Senate poised to split town next week for a home-state work period. “Senate Democrats should stay in town and focus on the last act in this battle,” said Fred Wertheimer, who leads the good government group Democracy 21. The latest measure blocked by Republicans Wednesday is different from an earlier voting bill from Democrats that would have touched on every aspect of the electoral process. It has a narrower focus and would restore the Justice Department’s ability to police voting laws in states with a history of discrimination. The measure drew the support of one Republican, Alaska Sen. Lisa Murkowski after Democrats agreed to make changes that she sought. But all other Republicans opposed opening debate on the bill. “Every time that Washington Democrats make a few changes around the margins and come back for more bites at the same apple, we know exactly what they are trying to do,” said Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, who slammed the vote as “political theatre” on a trumped-up a “go-nowhere bill.” Murkowski, too, said she still had underlying issues with the bill as written while criticizing Schumer’s decision to force repeated “show votes.” “Let’s give ourselves the space to work across the aisle,” she said Wednesday. “Our goal should be to avoid a partisan bill, not to take failing votes over and over.” The Democrats’ John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, named for the late Georgia congressman who made the issue a defining one of his career, would restore voting rights protections that have been dismantled by the Supreme Court. Under the proposal, the Justice Department would again police new changes to voting laws in states that have racked up a series of “violations,” drawing them into a mandatory review process known as “preclearance.” The practice was first put in place under the Voting Rights Act of 1965. But it was struck down by a conservative majority on the Supreme Court in 2013, which ruled the formula for determining which states needed their laws reviewed was outdated and unfairly punitive. The court did, however, say that Congress could come up with a new formula. The bill does just that. A second ruling from the high court in July made it more difficult to challenge voting restrictions in court under another section of the law. The law’s “preclearance” provisions had been reauthorized by Congress with overwhelming bipartisan support five times since it was first passed decades ago. But after the Supreme Court’s 2013 ruling, Republican support for the measure cratered. Though the GOP has shown no indication that its opposition will waver, there are signs that some of the voting changes Democrats seek aren’t as electorally advantageous for the party as some hope. Republican Glenn Youngkin’s victory in Virginia’s Tuesday gubernatorial election offers the latest test case. Democrats took control of all parts of Virginia’s government in 2019 and steadily started liberalizing the state’s voting laws. They made mail voting accessible to all and required a 45-day window for early voting, among the longest in the country. This year they passed a voting rights act that made it easier to sue for blocking ballot access. But those changes didn’t hurt Youngkin, who comfortably beat Democrat Terry McAuliffe, a popular former governor seeking a valedictory term. That’s still unlikely to change Republicans’ calculus. “Are we all reading the tea leaves from Virginia? Yes, absolutely,” Murkowski said. “Will it be something colleagues look to? It’s just one example.” Democratic frustration is growing, meanwhile leading to increasingly vocal calls to change the filibuster. “We can’t even debate basic bills,” said Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar, a Democrat. “The next step is to work on ideas to restore the Senate.” Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Joe Biden urges bill over ‘finish line’ as Dems eye new surtax

With his signature domestic initiative at stake, President Joe Biden is urging Democrats to wrap up talks and bring the social services and climate change bill “over the finish line” before he departs Thursday for global summits overseas. Top Democratic leaders are signaling a deal is within reach even though momentum fizzled and tempers flared late Wednesday after a billionaires’ tax and a paid family leave program fell out of the Democrats’ sweeping bill, mostly to satisfy a pivotal senator in the 50-50 Senate. But expanded health care programs, free pre-kindergarten, and some $500 billion to tackle climate change remain in the mix in what’s now at least a $1.75 trillion package. And Democrats are eyeing a new surcharge on the wealthy — 5% on incomes above $10 million and an additional 3% on those beyond $25 million — to help pay for it, according to a person who requested anonymity to discuss the private talks. “They’re all within our reach. Let’s bring these bills over the finish line.” Biden tweeted late Wednesday. Biden could yet visit Capitol Hill before traveling abroad, and House Democrats were set to meet in the morning. Besides pressing for important party priorities, the president was hoping to show foreign leaders the U.S. was getting things done under his administration. The administration is assessing the situation “hour by hour,” White House press secretary Jen Psaki said. It was a fast-moving day on Capitol Hill that started upbeat as House Speaker Nancy Pelosi declared that Democrats were in “pretty good shape.” But hopes quickly faded as Biden’s big proposal ran into stubborn new setbacks, chief among them how to pay for it all. A just-proposed tax on billionaires could be scrapped after Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia objected, according to a senior party aide, who requested anonymity to discuss the private talks. The billionaires’ tax proposal had been designed to win over another Democratic holdout, Sen. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, but Manchin panned it as unfairly targeting the wealthy, leaving Democrats at odds. “People in the stratosphere, rather than trying to penalize, we ought to be pleased that this country is able to produce the wealth,” Manchin told reporters. Manchin said he prefers a minimum 15% flat “patriotic tax” to ensure the wealthiest Americans don’t skip out on paying any taxes. Nevertheless, he said: “We need to move forward.” Next to fall was a proposed paid family leave program that was already being chiseled back from 12 to four weeks to satisfy Manchin. But with his objections, it was unlikely to be included in the bill, the person said. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., had devised several new options for Manchin’s review and told reporters late in the evening, “It’s not over until it’s over.” Together, Manchin’s and Sinema’s objections packed a one-two punch, throwing Biden’s overall plan into flux, halving what had been a $3.5 trillion package, and infuriating colleagues along the way. In the evenly divided Senate, Biden needs all Democrats’ support with no votes to spare. White House officials met at the Capitol with Manchin and Sinema, two senators who now hold enormous power, essentially deciding whether or not Biden will be able to deliver on the Democrats’ major campaign promises. “Making progress,” Sinema said as she dashed into an elevator. A Sunday deadline loomed for approving a smaller, bipartisan roads-and-bridges infrastructure bill or risk allowing funds for routine transportation programs to expire. But that $1 trillion bill has been held up by progressive lawmakers who are refusing to give their support without the bigger Biden deal. Despite a series of deadlines, Democrats have been unable to close the deal among themselves, and Republicans overwhelmingly oppose the package. At best, Democrats could potentially reach a framework Thursday that could send Biden overseas with a deal in hand and unlock the process while the final details were sewn up. Applying pressure, Pelosi announced a Thursday committee hearing to spur the Biden package along toward a full House vote, though the timing remained uncertain. Democrats had hoped the unveiling of the billionaires tax Wednesday could help resolve the revenue side of the equation after Sinema rejected the party’s earlier idea of reversing Donald Trump-era tax breaks on corporations and the wealthy, those earning more than $400,000. The new billionaires’ proposal would tax the gains of those with more than $1 billion in assets or incomes of more than $100 million over three consecutive years — fewer than 800 people — requiring them to pay taxes on the gains of stocks and other tradeable assets, rather than waiting until holdings are sold. The billionaires’ tax rate would align with the capital gains rate, now 23.8%. Democrats have said it could raise $200 billion in revenue that could help fund Biden’s package over ten years. Republicans have derided the billionaires’ tax as “harebrained,” and some have suggested it would face a legal challenge. But Democratic Sen. Ron Wyden of Oregon, chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, insisted the billionaires tax remains on the table. “I’ve not heard a single United States senator — not one — get up and say, ‘Gee, I think it’s just fun that billionaires pay little or nothing for years on end,’” Wyden said. More likely in the mix was the companion proposal, a new 15% corporate minimum tax, as well as the new surtax being proposed on higher incomes above $10 million. Together they are designed to fulfill Biden’s desire for the wealthy and big business to pay their “fair share.” They also fit his promise that no new taxes hit those earning less than $400,000 a year, or $450,000 for couples. Biden wants his package fully paid for without piling on debt. Resolving the revenue side has been crucial, as lawmakers figure out how much money will be available to spend on the new health, child care, and climate change programs in Biden’s big plan. Among Democrats, Rep. Richard Neal of Massachusetts, the chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, said he told Wyden

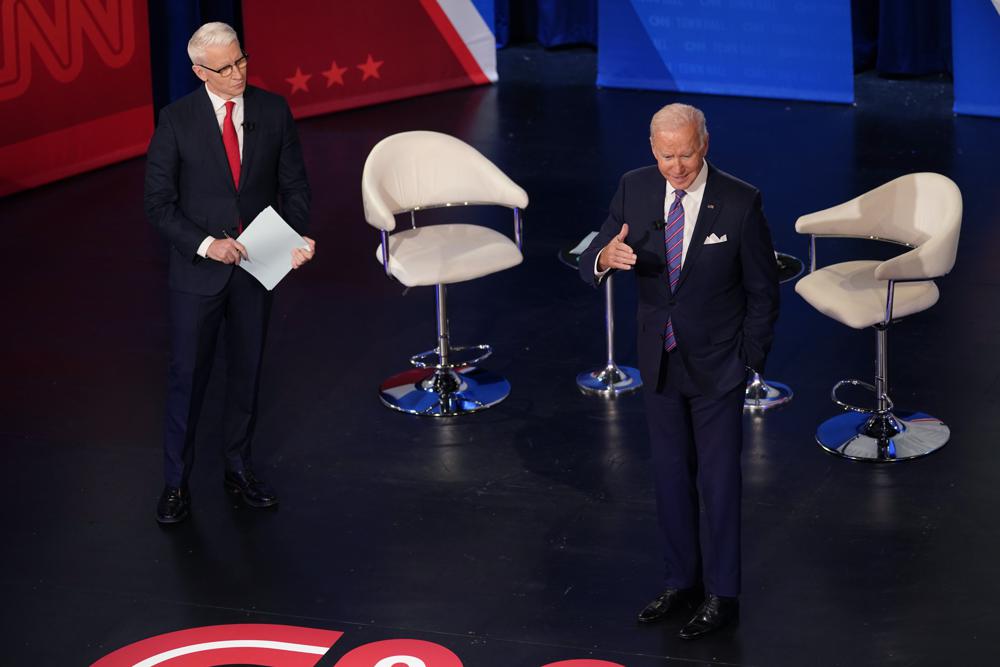

White House, Dems hurriedly reworking $2 trillion Joe Biden plan

The White House and Democrats are hurriedly reworking key aspects of President Joe Biden’s $2 trillion domestic policy plan, trimming the social services and climate change programs and rethinking new taxes on corporations and the wealthy to pay for a scaled-back package. The changes come as Biden more forcefully appeals to the American public, including in a televised town hall Thursday, for what he says are the middle-class values at the heart of his proposal. Biden mentioned during the evening event the challenge he faces in wrangling the sharply divergent factions in the Democratic party to agree to the final contours of the bill. With an evenly divided Senate, he can’t afford to lose a single vote, and he is navigating the competing demands of progressives, who want major investments in social services, and centrists, who want to see the price tag on the package come down. “When you’re president of the United States, you have 50 Democrats — every one is a president. Every single one. So you gotta work things out,” he said during a CNN town hall. Still, he expressed optimism about the process, saying “I think so” when asked if Democrats were close to a deal. “It’s all about compromise. Compromise has become a dirty word, but bipartisanship and compromise still has to be possible,” he said. Biden later said the discussions are “down to four or five issues.” On one issue — the taxes to pay for the package — the White House idea seemed to be making headway with a new strategy of abandoning plans for reversing Trump-era tax cuts in favor of an approach that would involve taxing the investment incomes of billionaires to help finance the deal. Biden has faced resistance from key holdouts, in particular Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz., who has not been on board with her party’s plan to undo President Donald Trump’s tax breaks for big corporations or individuals earning more than $400,000 a year. The president was unusually forthcoming Thursday night about the sticking points in the negotiations with Sinema and another key Democrat, conservative Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia. While the president said Sinema “will not raise a single penny in taxes” on the wealthy or corporations, a White House official later clarified that the president was referring to raising the top tax rates, not the range of tax proposals, “which Senator Sinema supports.” Biden said Manchin doesn’t want to “rush” the transition to clean energy so quickly it will result in major job losses in his coal-producing state. Even as he seemed encouraged by progress, Biden acknowledged major reductions to his original vision. He signaled the final plan would no longer provide free community college but said he hoped to increase Pell Grants to compensate for the loss of the policy. “It’s not going to get us the whole thing, but it is a start,” he said. He also said that what had been envisioned as a federally paid, months-long family leave program would be just four weeks. As long-sought programs are adjusted or eliminated, Democratic leaders are working to swiftly wrap up talks, possibly in the days ahead. Talks between the White House and Democratic lawmakers are focused on reducing what had been a $3.5 trillion package to about $2 trillion in what would be an unprecedented federal effort to expand social services for millions and address the rising threat of climate change. “We have a goal. We have a timetable. We have milestones, and we’ve met them all,” said House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., who predicted Thursday, “It will pass soon.” An abrupt change, of course, came late Wednesday when the White House floated new ways to pay for parts of the proposal. Biden himself signaled flexibility on the tax provisions of the bill, as long as it’s paid for and it doesn’t increase taxes on those earning $400,000 or less. “I’m willing to make sure that we pay for everything,” he said when pressed on what tax proposal he’d support. The newly proposed tax provisions, though, are likely to sour progressives and even some moderate Democrats who have long campaigned on scrapping the Republican-backed 2017 tax cuts that many believe unduly reward the wealthy and cost the government untold sums in lost revenue at a time of gaping income inequality. Many are furious that perhaps a lone senator could stymie that goal. The chairman of the tax-writing Ways & Means Committee, Rep. Richard Neal, D-Mass., said he spoke for more than 30 minutes with the centrist Arizona senator, whose closely held views are a mystery to her colleagues. “I said, Kyrsten, you and I both know this has got to pass. She said: ‘I couldn’t agree more,’” Neal told reporters at the Capitol. Sinema’s office did not respond to a request for comment. Under existing law passed in 2017, the corporate tax rate is 21%. Democrats had proposed raising it to 26.5% for companies earning more than $5 million a year. The top individual income tax rate would go from 37% to 39.6% for those earning more than $400,000, or $450,000 for married couples. Under the changes being floated, the corporate rate would not change. But the revisions would not be all positive for big companies and the wealthy. The White House is reviving the idea of a minimum corporate tax rate, similar to the 15% rate Biden had proposed this year. That’s even for companies that say they had no taxable income — a frequent target of Biden, who complains they pay “zero” in taxes. The new tax on the wealthiest individuals would be modeled on legislation from Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., chairman of the Senate Finance Committee. He has proposed taxing stock gains of people with more than $1 billion in assets — fewer than 1,000 Americans. Other tax options are also being considered, and Democrats are almost certain to include a provision to beef up the Internal Revenue Service to go after tax dodgers. Biden and his party are trying to shore up middle-class households, tackle climate

Joe Biden can’t budge fellow Dems with big overhaul at stake

His government overhaul plans at stake, President Joe Biden appeared unable Wednesday night to swiftly strike an agreement with two wavering Democratic senators trying to trim back his potentially historic $3.5 trillion measure that will collapse without their support. With Republicans solidly opposed and no Democratic votes to spare, Biden canceled a trip to Chicago that was to focus on COVID-19 vaccinations so he could dig in for a full day of intense negotiations ahead of crucial votes. Aides made their way to Capitol Hill for talks, and late in the day, supportive House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer met with Biden at the White House. The risks were clear, but so was the potential reward as Biden and his party reach for a giant legislative accomplishment — promising a vast rewrite of the nation’s balance sheet with an ever-slim majority in Congress. His idea is to essentially raise taxes on corporations and the wealthy and use that money to expand government health care, education, and other programs — an impact that would be felt in countless American lives. “We take it one step at a time,” Pelosi told reporters. Attention is focused on Sens. Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, centrist Democrats. They share a concern that the overall size of Biden’s plan is too big but have infuriated colleagues by not making any counter-proposals public. In a possibly ominous sign, Manchin sent out a fiery statement late Wednesday, decrying the broad spending as “fiscal insanity” and warning it would not get his vote without adjustments. “I cannot – and will not – support trillions in spending or an all-or-nothing approach,” he said. Together, the two senators hold the keys to unlocking the stalemate over Biden’s sweeping vision, the heart of his campaign pledges. While neither has said no to a deal, they have yet to signal yes — but they part ways on specifics, according to a person familiar with the private talks, and granted anonymity to discuss them. Manchin appears to have fewer questions about the revenue side of the equation — the higher taxes on corporations and the wealthy — than the spending plans and particular policies, especially those related to climate change that are important to his coal-centric state. He wants any expansion of aid programs to Americans to be based on income needs, not simply for everyone. Though Sinema is less publicly open in her views, she focuses her questions on the menu of tax options, including the increased corporate rate that some in the business community argue could make the U.S. less competitive overseas and the individual rate that others warn could snare small business owners. With Democrats’ campaign promises on the line, the chairwoman of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, Rep. Pramila Jayapal of Washington state, said of Manchin: “He needs to either give us an offer or this whole thing is not going to happen.” Pelosi suggested she might postpone Thursday’s vote on a related $1 trillion public works measure that Manchin, Sinema, and other centrists want but that progressives are threatening to defeat unless there’s movement on Biden’s broader package. Thursday’s vote has been seen as a pressure point on the senators and other centrist lawmakers to strike an agreement with Biden. But with Manchin and Sinema dug in, that seemed unlikely. “Both bills are must-pass priorities,” according to a White House readout of the president’s meeting with the congressional leaders. At the same time, Congress is starting to resolve a more immediate crisis that arose after Republicans refused to approve legislation to keep the government funded past Thursday’s fiscal yearend and raise the nation’s debt limit to avoid a dangerous default on borrowing. Democrats are separating the government funding and debt ceiling vote into two bills, stripping out the more-heated debate over the debt limit for another day, closer to a separate October deadline. The Senate is poised to vote Thursday to provide government funding to avoid a federal shutdown, keeping operations going temporarily to Dec. 3. The House is expected to quickly follow. With Biden and his party stretching to achieve what would be a signature policy achievement, there is a strong sense that progress is being made on the big bill, said an administration official who requested anonymity to discuss the private talks. The president is highly engaged, meeting separately with Manchin and Sinema at the White House this week and talking by phone with lawmakers shaping the package. He even showed up at Wednesday evening’s annual congressional baseball game, a gesture of goodwill during the rare bipartisan event among lawmakers. To reach an accord, Democrats are poised to trim the huge Biden measure’s tax proposals and spending goals to reach an overall size Manchin and Sinema are demanding. “I think it’s pretty clear we’re in the middle of a negotiation and that everybody’s going to have to give a little,” said White House press secretary Jen Psaki. Psaki said members of Congress “are not wallflowers” but have a range of views. “We listen, we engage, we negotiate. But ultimately, there are strong viewpoints and what we’re working to do is get to an agreement.” Besides senators, Biden’s problems with fellow Democrats also include a small number of centrist House Democrats who are also are bristling at the far-reaching scope of his domestic agenda, which would expand health care, education, and climate change programs, all paid for by the higher tax rates. Progressive lawmakers warn against cutting too much, saying they have already compromised enough, and threatening to withhold support for the companion $1 trillion public works measure that they say is too meager without Biden’s bigger package assured. But centrists warned off canceling Thursday’s vote as a “breach of trust that would slow the momentum in moving forward in delivering the Biden agenda,” said Rep. Stephanie Murphy, D-Fla., a leader of the centrist Blue Dog Democrats. Republicans are opposed to Biden’s bigger vision, deriding the $3.5 trillion package

Debt ceiling battle looms ahead of Congress’ return

As Congress prepares to return from August recess, President Joe Biden’s plans for trillions in federal spending hang in the balance. Congressional Republicans are making clear they intend to oppose the full brunt of the significant increase in federal spending, in particular Democrats’ plans to raise the debt ceiling. More than 100 Republicans have backed a public letter vowing not to raise the debt ceiling, which was surpassed in July and would need to be increased before enacting Biden’s federal spending plans. “Democrats have embarked on a massive and unprecedented deficit spending spree,” the letter says. “Without a single Republican vote, they passed a $1.9 trillion ‘Covid relief’ bill in March. Now they have passed a $3.5 trillion Budget Resolution, again without a single Republican vote.” The debt ceiling could become a rallying point for Republicans looking to take a stand against Biden’s $1 trillion infrastructure bill and the following $3.5 trillion reconciliation bill, both of which are in flux. “In order for this spending to occur, our nation’s debt limit will have to be increased significantly,” the letter says. “Because Democrats are responsible for the spending, they need to take responsibility for increasing the debt ceiling. They have total control of the government and the unilateral ability to raise the debt ceiling to accommodate their unilateral spending plans. … Doing so would not require a single Republican vote and would appropriately require each and every Democrat to take responsibility for their out-of-control spending.” Republicans have taken issue with a range of provisions in the bills, but inflation, gas prices, immigration amnesty, and Green New Deal measures have taken center stages as they rally opposition. “Joe Biden and Congressional Democrats are inflaming disasters that they created,” said Rep. Jim Banks of Indiana, one of the leading members behind the letter. “Thanks to their spending-fueled inflation, Americans’ paychecks have effectively been slashed. What’s Democrats’ plan? Spend another $3.5 trillion. Our border is overwhelmed, so they’re pushing for the largest amnesty in history. Gas prices have skyrocketed, and they want the Green New Deal.” House Republicans have allies in the Senate on this issue. Earlier this month, 46 Republican Senators signed a letter pledging they would not vote to raise the debt ceiling. The letters from Republicans in both chambers give an idea of how the party will message its opposition to Biden’s spending, which does have some popular provisions. So far, the bill’s opponents have balked at the high price tag, including Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., and Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz, who said they cannot support a $3.5 trillion bill. “However, I have serious concerns about the grave consequences facing West Virginians and every American family if Congress decides to spend another $3.5 trillion,” Manchin said after the bill’s release. “Over the past year, Congress has injected more than $5 trillion of stimulus into the American economy – more than any time since World War II – to respond to the pandemic.” By Casey Harper | The Center Square

Democrats unveil plan to update landmark voting law

House Democrats on Tuesday put forward a new proposal to update the landmark Voting Rights Act, seeking against long odds to revive the civil rights-era legislation that once served as a barrier against discriminatory voting laws. The bill, introduced by Rep. Terri Sewell of Alabama, seeks to restore a key provision of the federal law that compelled states with a history of discrimination to undergo a federal review of changes to voting and elections. The Supreme Court set aside the formula that decided which jurisdictions were subject to the requirement in a 2013 decision and weakened the law further in a ruling this summer. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., pledged to move quickly and said Democrats plan to pass the bill when the House returns next week. “With the attack on the franchise escalating and states beginning the process of redistricting, we must act,” Pelosi said in a statement. The push comes at a time when a number of Republican-led states have passed laws tightening rules around voting, particularly mail ballots. Democrats have sounded the alarm about the new hurdles to voting, comparing the impact on minorities to the disenfranchisement of Jim Crow laws, but they have struggled to unite behind a strategy to overcome near-unanimous Republican opposition in the Senate. The new House bill, known as H.R. 4, is named after Georgia congressman and civil rights leader John Lewis, who died last year. Sewell announced the introduction of the bill in front of the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, where Lewis was beaten during a civil rights march in 1965. The Voting Rights Act was signed into law a few months later. “We’re not looking to punish or penalize anyone. This is about restoring equal access to the ballot box. It’s about ensuring that Americans know their vote counts and their vote will count at the ballot box,” Sewell said. The Lewis bill outlines a new, expanded formula that the Department of Justice can use to identify discriminatory voting patterns in states and local jurisdictions. Those entities would then need to get DOJ approval before making further changes to elections. The bill also includes a provision designed to counter the summer’s Supreme Court ruling that made it harder to challenge potentially discriminatory voting changes. A companion bill pushed by Democrats, known as the For the People Act, has stalled in the Senate amid Republican opposition and disagreement among Democrats about whether to change procedural rules in the evenly divided Senate to get it passed. Democrats have argued both bills are needed to safeguard access to the ballot. They emphasize that the update to the Voting Rights Act would not apply to many voting changes already made by the states. The For the People Act, on the other hand, would create minimum voting standards in the U.S., such as same-day and automatic voter registration, early voting, and no-excuse absentee voting. The bill would also change various campaign finance and ethics laws. Senate Democrats have pledged to take up that more expansive bill when they return next month as the first order of business, though it is unclear how they can maneuver around GOP opposition. Republicans signaled they’ll try to stop the John Lewis Act much as they have the For the People Act. “This bill is a federal power grab and a gift to partisan, frivolous litigators who will use it to manipulate state laws and throw all federal elections into chaos, further undermining voter confidence in fair and accurate elections,” said Jason Snead, executive director of Honest Elections Project Action, a conservative advocacy group. Voting rights groups have been putting pressure on Democrats to eliminate or change the filibuster rules in the Senate, which requires 60 votes to proceed with most legislation, to get around the broad GOP opposition to the bills. That partisan opposition leaves Democrats well short of the needed support to advance them in the 50-50 Senate. At least two Democratic senators, Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona and Joe Manchin of West Virginia, have said they oppose eliminating the filibuster though discussions are ongoing about potential changes to the rules. Groups that back the voting measures are planning marches in several cities on Aug. 28 to call on the Senate to remove the filibuster rule. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Big win for $1T infrastructure bill: Dems, GOP come together

With a robust vote after weeks of fits and starts, the Senate approved a $1 trillion infrastructure plan for states coast to coast on Tuesday, as a rare coalition of Democrats and Republicans joined together to overcome skeptics and deliver a cornerstone of President Joe Biden’s agenda. “Today, we proved that democracy can still work,” Biden declared at the White House, noting that the 69-30 vote included even Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell. “We can still come together to do big things, important things, for the American people,” Biden said. The overwhelming tally provided fresh momentum for the first phase of Biden’s “Build Back Better” priorities, now heading to the House. A sizable number of lawmakers showed they were willing to set aside partisan pressures, at least for a moment, eager to send billions to their states for rebuilding roads, broadband internet, water pipes, and the public works systems that underpin much of American life. The vote also set the stage for a much more contentious fight over Biden’s bigger $3.5 trillion package that is next up in the Senate — a more liberal undertaking of child care, elder care, and other programs that is much more partisan and expected to draw only Democratic support. That debate is expected to extend into the fall. With the Republicans lockstep against the next big package, many of them reached for the current compromise with the White House because they, too, wanted to show they could deliver and the government could function. “Today’s kind of a good news, bad news day,” said Alaska Sen. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, one of the negotiators. “The good news is that today we really did something historic in the United States Senate; we moved out an infrastructure package, something that we have talked about doing for years.” The bad news, she said, is what’s coming next. Infrastructure was once a mainstay of lawmaking, but the weeks-long slog to strike a compromise showed how hard it has become for Congress to tackle routine legislating, even on shared priorities. Tuesday’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act started with a group of 10 senators who seized on Biden’s campaign promise to draft a scaled-down version of his initial $2.3 trillion proposal, one that could more broadly appeal to both parties in the narrowly divided Congress, especially the 50-50 Senate. It swelled to a 2,700-page bill backed by the president and also business, labor, and farm interests. Over time, it drew an expansive alliance of senators and a bipartisan group in the House. In all, 19 Republicans joined all Democrats in voting for Senate passage. Vice President Kamala Harris, as presiding officer, announced the final tally. While liberal lawmakers said the package doesn’t go far enough as a down-payment on Biden’s priorities and conservatives said it is too costly and should be more fully paid for, the coalition of centrist senators was able to hold. Even broadsides from former President Donald Trump could not bring the bill down. The measure proposes nearly $550 billion in new spending over five years in addition to current federal authorizations for public works that will reach virtually every corner of the country — a potentially historic expenditure Biden has put on par with the building of the transcontinental railroad and Interstate highway system. There’s money to rebuild roads and bridges and also to shore up coastlines against climate change, protect public utility systems from cyberattacks and modernize the electric grid. Public transit gets a boost, as do airports and freight rail. Most lead drinking water pipes in America could be replaced. Sen. Rob Portman of Ohio, the lead Republican negotiator, said the work “demonstrates to the American people that we can get our act together on a bipartisan basis to get something done.” The top Democratic negotiator, Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, said rarely will a piece of legislation affect so many Americans. She gave a nod to the late fellow Arizona Sen. John McCain and said she was trying to follow his example to “reach bipartisan agreements that try to bring the country together.” Drafted during the COVID-19 crisis, the bill would provide $65 billion for broadband, a provision Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, negotiated because she said the coronavirus pandemic showed that such service “is no longer a luxury; it is a necessity.” States will receive money to expand broadband and make it more affordable. Despite the momentum, action slowed last weekend when Sen. Bill Hagerty, a Tennessee Republican allied with Trump, refused to speed up the process. Trump had called his one-time Japan ambassador and cheered him on, but it’s unclear if the former president’s views still carry as much sway with most senators. Trump issued fresh complaints hours before Tuesday’s vote. He had tried and failed to pass his own infrastructure bill during his time in the White House. Other Republican senators objected to the size, scope, and financing of the package, particularly concerned after the Congressional Budget Office said it would add $256 billion to deficits over the decade. Rather than pressure his colleagues, Senate Republican leader McConnell of Kentucky stayed behind the scenes for much of the bipartisan work. He allowed the voting to proceed and may benefit from enabling this package in a stroke of bipartisanship while trying to stop Biden’s next big effort. Unlike the $3.5 trillion second package, which would be paid for by higher tax rates for corporations and the wealthy, the bipartisan measure is to be funded by repurposing other money, including some COVID-19 aid. The bill’s backers argue that the budget office’s analysis was unable to take into account certain revenue streams that will help offset its costs — including from future economic growth. Senators have spent the past week processing nearly two dozen amendments, but none substantially changed the framework. The House is expected to consider both Biden infrastructure packages together, but centrist lawmakers urged Speaker Nancy Pelosi to bring the bipartisan plan forward quickly, and they raised concerns about the bigger bill in a sign of the complicated politics still ahead. After the Senate vote, she declared, “Today is a day of progress … a once in a century opportunity.”

Infrastructure on track as bipartisan Senate coalition grows

After weeks of fits, starts, and delays, the Senate is on track to give final approval to the $1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure plan, with a growing coalition of Democrats and Republicans prepared to lift the first phase of President Joe Biden’s rebuilding agenda to passage. Final Senate votes are expected Tuesday, and the bill would then go to the House. All told, some 70 senators appear poised to carry the bipartisan package to passage, a potentially robust tally of lawmakers eager to tap the billions in new spending for their states and to show voters back home they can deliver. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer said it’s “the first time the Senate has come together around such a package in decades.” The often elusive political center is holding steady, a rare partnership with Biden’s White House. On the left, the Democrats have withstood the complaints of liberals who say the proposal falls short of what’s needed to provide a down payment on one of the president’s top priorities. From the right, the Republicans are largely ignoring the criticism from their most conservative and far-flung voices, including a barrage of name-calling from former President Donald Trump as he tries to derail the package. Together, a sizable number of business, farm, and labor groups back the package, which proposes nearly $550 billion in new spending on what are typically mainstays of federal spending — roads, bridges, broadband internet, water pipes, and other public works systems that cities and states often cannot afford on their own. “This has been a different sort of process,” said Sen. Rob Portman of Ohio, the lead Republican negotiator of the group of 10 senators who drafted the package. Portman, a former White House budget director for George W. Bush, said the investments being made have been talked about for years yet never seem to get done. He said, “We’ll be getting it right for the American people.” The top Democratic negotiator, Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, said she was trying to follow the example of fellow Arizonan John McCain to “reach bipartisan agreements that try to bring the country together.” Still, not all senators are on board, Despite the momentum, action ground to a halt over the weekend when Sen. Bill Hagerty, a Tennessee Republican allied with Trump, refused to speed up the process. Other Republican senators objected to the size, scope, and financing of the package, particularly concerned after the Congressional Budget Office said it would add $256 billion to deficits over the decade. Two Republicans, Sens. Jerry Moran of Kansas and Todd Young of Indiana, had been part of initial negotiations shaping the package but ultimately announced they could not support it. Rather than pressure lawmakers, Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky has stayed behind the scenes for much of the bipartisan work. He has cast his own votes repeatedly to allow the bill to progress, calling the bill a compromise. Trump called Hagerty, who had been his ambassador to Japan, on Sunday, and the senator argued for taking more time for debate and amendments, in part because he wants to slow the march toward Biden’s second phase, a $3.5 trillion bill that Republicans fully oppose. The outline for the bigger $3.5 trillion package is on deck next in the Senate — a more liberal undertaking of child care, elder care, and other programs that is much more partisan and expected to draw only Democratic support. That debate is expected to extend into the fall. Unlike Biden’s bigger $3.5 trillion package, which would be paid for by higher tax rates for corporations and the wealthy, the bipartisan package is to be funded by repurposing other money and with other spending cuts and revenue streams. The bill’s backers argue that the budget office’s analysis was unable to take into account certain revenue streams — including from future economic growth. Senators have spent the past week processing nearly two dozen amendments to the 2,700-page package, but so far, none has substantially changed its framework. One remaining issue, over tax compliance for cryptocurrency brokers, appeared close to being resolved after senators announced they had worked with the Treasury Department to clarify the intent. But an effort to quickly adopt the cryptocurrency compromise was derailed by senators who wanted their own amendments, including one to add $50 billion for shipbuilding and other defense infrastructure. It’s unclear if any further amendments will be adopted. The House is expected to consider both Biden infrastructure packages when it returns from recess in September. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has said the two bills will be considered together, but on Monday, a bipartisan group of centrist lawmakers urged her to bring their smaller plan forward quickly, raising concerns about the bigger bill, in a sign of the complicated politics ahead. “This once-in-a-century investment deserves its own consideration,” wrote Reps. Josh Gottheimer, D-N.J., Jared Golden, D-Maine, and others in a letter obtained by The Associated Press. “We cannot afford unnecessary delays.” Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

With John McCain in mind, Kyrsten Sinema reaches for bipartisanship

More than for her shock of purple hair or unpredictable votes, Democratic Sen. Kyrsten Sinema is perhaps best known for doing the unthinkable in Washington: She spends time on the Republican side of the aisle. Not only does she pass her days chatting up the Republican senators, she has been known to duck into their private GOP cloakroom — absolutely unheard of — and banter with the GOP leadership. She and Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell talk often by phone. Sinema’s years in Congress have been a whirlwind of political style and perplexing substance, an antiwar liberal-turned-deal-making centrist who now finds herself at the highest levels of power. A key negotiator of the bipartisan infrastructure compromise, she was among those President Joe Biden first called to make the deal — and then called upon again as he worked furiously to salvage the agreement from collapse. A holdout to changing the Senate’s filibuster rules, she faces enormous pressure to act as voting rights in her own state and others hang in the balance. “If anybody can pull this off it’s Kyrsten,” said David Lujan, a former Democratic colleague of Sinema’s in the Arizona statehouse. “She’s incredibly smart, so she can figure out where people’s commonalities are and get things done.” The senator’s theory of the case of how to govern in Washington will be tested in the weeks ahead as Congress works to turn the infrastructure compromise into law and mounts a response to the Supreme Court decision upholding Arizona’s strict new voting rules. She is modeling her approach on the renegade style of Arizona Sen. John McCain, who died in 2018 and was known for his willingness to reach across the aisle. But aspiring to bold bipartisanship is challenging in the post-Trump era of hardened political bunkers and fierce cultural tribalism. Many in her own party scoff at her overtures to the GOP and criticize her for not playing hardball. Her name is now uttered alongside West Virginia’s Sen. Joe Manchin as the two Democrats standing in the way of changing the filibuster rules requiring 60 votes to advance legislation — a priority for liberals working to pass Biden’s agenda in the split 50-50 Senate. This year she cast a procedural vote against raising the minimum wage and has opposed the climate change-focused Green New Deal, even though she’s not fully opposed to either policy. She declined a request for an interview. “It’s the easiest thing in the world for politicians to declare bipartisanship dead and line up on respective sides of a partisan battle,” she said in a statement to The Associated Press. “What’s harder is getting out of our comfort zones, finding common ground with unlikely allies, and forming coalitions that can achieve durable, lasting results.” Sinema arrived in Washington with a burst of energy and a swoosh of fashion. She quickly became known as one of the best vote counters in the House, on par with Speaker Nancy Pelosi, because of her visits to the other side of the aisle. She voted against Pelosi more than once for speaker. Her maiden speech in the Senate drew from McCain’s farewell address, a marker of where she was headed. She changed the decades-old Senate dress code by simply wearing whatever she wants — and daring anyone to stop her. The purple wig was a nod to the coronavirus pandemic’s lockdown. (In off hours, she has been spotted wearing a ring with an expletive similar to “buzz off.”) “People may debate her sincerity, but the truth is, she makes an active decision that she’s going to work well with other people — and I haven’t seen her slip up,” said Republican Rep. Patrick McHenry of North Carolina, who served with her in the House. Sinema’s status as a bipartisan leader fascinates those who’ve watched her decades-long rise in Arizona politics, where she began as a lonely left-wing activist who worked for Ralph Nader’s 2000 Green Party presidential campaign and then slowly retooled herself into a moderate advocate of working across the aisle. “Ideologically, it does surprise me,” Steven Yarbrough, a Republican who served 12 years with Sinema in the Arizona legislature, said of her transformation. “But given how smart and driven she is, well, that doesn’t surprise me at all.” That Sinema even made it that far seemed improbable. Her parents divorced when she was young, and she moved with her mother and stepfather from Tucson to the Florida panhandle, where she lived in an abandoned gas station for three years. Driven to succeed, she graduated from the local high school as valedictorian at age 16 and earned her bachelor’s degree from Brigham Young University in Utah at age 18, leaving the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, in which she’d been raised, after graduation. Sinema landed in Phoenix, where she earned several more degrees — including a law degree and a doctorate — worked as a social worker and then a lawyer, vociferously protested the Iraq War and fought for immigrant and LGBTQ rights at a time when Arizona was veering right. In 2004 she was elected to the state legislature representing a fairly liberal area and initially was a backbencher who lobbed rhetorical bombs from the left. But Sinema has written and spoken extensively of how she discovered the merits of moderation while serving in the GOP-controlled state legislature. She wrote a book titled “Unite and Conquer” about the need for leftists to compromise and cut deals. In 2006, she co-chaired a bipartisan group to fight a gay marriage ban on the ballot and had to decide whether to simply condemn the ban or try to defeat it, said Steve May, the Republican former state lawmaker who collaborated with her. An avid consumer of polling, she helped hit upon a strategy of targeting older, retired heterosexual couples who could also lose benefits under the ballot measure due to their unmarried status. They narrowly succeeded in defeating it. (Another ban passed two years later.) “She came from doing speeches and leading protests, and she learned she can actually win,” May said. When a