Juneteenth marked as state holiday in Alabama this year

Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey has authorized Juneteenth Day — the federal holiday marking the end of slavery — as a holiday for state workers this year in Alabama. Ivey issued a memo earlier this month authorizing the day as a holiday for state workers. State offices will be closed on June 20 for the holiday. Juneteenth, or June 19, falls on a Sunday this year, so the holiday will be recognized the following Monday. President Joe Biden signed legislation last year to make Juneteenth, or June 19, a federal holiday to recognize the end of slavery. Ivey authorized the holiday for state employees since it’s designated at the federal level, spokeswoman Gina Maiola wrote in an email. “However, it is important to remember that ultimately the Legislature must decide if this will become a permanent state holiday,” Maiola wrote. Alabama law recognizes all other national holidays in the state as permanent state holidays, with the exception of Juneteenth. Juneteenth commemorates June 19, 1865, when Union soldiers brought the news of freedom to enslaved Black people in Galveston, Texas — two months after the Confederacy had surrendered. That was also about 2 1/2 years after the Emancipation Proclamation freed slaves in the Southern states. Alabama has three state Confederate-related holidays that close state offices for the day. Alabama marks Confederate Memorial Day in April and the birthday of Confederate President Jefferson Davis in June. The state jointly observes Robert E. Lee Day with Martin Luther King, Jr. Day in January. There have been various efforts to abolish or change the name of Confederate-related holidays, but none has been successful. Republished with the permission of The Associated Press.

Alabama church of ‘Bloody Sunday’ on endangered places list

Like religious congregants all over, the people of historic Brown Chapel AME Church turned off the lights and locked the doors at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic because it wasn’t safe to gather for worship with a deadly virus circulating. For a time, the landmark church that launched a national voting rights movement in Selma, Alabama, was off-limits. What members found when they returned was heartbreaking: Termites had eaten so much wood that parts of the structure weren’t stable anymore, said member Juanda Maxwell, and water leaks damaged walls. Mold was growing in parts of the building, where hundreds met before Alabama state troopers attacked voting rights demonstrators on Bloody Sunday in 1965 at the Edmund Pettus Bridge. “It’s in horrible shape,” said Maxwell. “It’s a tough time. Because we were closed for a year, it exacerbated the problem with water coming in.” The red brick church, with distinctive twin bell towers and a domed ceiling, tops this year’s list of the nation’s most endangered historic places, according to the Washington, D.C.-based National Trust for Historic Preservation, a nonprofit organization which works to highlight and preserve sites that are in danger of being lost. Other places on the list include: — Chicano/a Murals painted on the sides of buildings in Colorado and inspired by the human rights and cultural movements of the 1960s and ’70s. — The Deborah Chapel, a Jewish mortuary building established in 1886 in Hartford, Connecticut. — Francisco Sanchez Elementary School, the closed centerpiece of the town in Umatac, Guam. — Minidoka National Historic Site, where more than 13,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II in Jerome, Idaho. — Camp Naco, a base for Black Buffalo Soldiers dating back to 1919 along the U.S.-Mexican border in Naco, Arizona. — Picture Cave in Warrenton, Missouri, which holds indigenous artwork dating as far back more than 1,200 years by the Osage Nation. — Brooks Park Art and Nature Center, the home and art studio in East Hampton, New York, of James Brooks and Charlotte Park, who were important in the abstract expressionism movement in American art. — Palmer Memorial Institute, a boarding school built in 1902 for Black youths in Greensboro, North Carolina. — Olivewood Cemetery, an African American burial ground in Houston, Texas, dating to 1875 and containing more than 4,000 graves. — Jamestown, the site in Jamestown, Virginia, where enslaved people first arrived in America and where the first publicly elected assembly in the United States met. Brown Chapel, the first African Methodist Episcopal church in Alabama, was the site of preparations for a voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery on March 7, 1965, when police beat marchers led by the late Rep. John Lewis, then a young activist. Weeks later, thousands gathered there before the Selma-to-Montgomery march led by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Maxwell is part of a group of Brown Chapel members serving on a foundation that’s trying to raise money for repairs estimated to exceed $4 million, she said. The church, located in a public housing community, has only a few dozen members in regular attendance, so it’s relying on grants and outside donations to fund the work. The National Park Service already has provided a grant of $1.3 million for the restoration of the church, which was constructed in 1908 by a formerly enslaved Black builder, A.J. Farley, and declared a National Historic Landmark in 1997. “Our goal is to try to receive over $3 million in grants to do the foundational work. After that we hope to get in more private donations,” Maxwell said. With members unable to gather in the building since repair work began in October, Maxwell said, the few who still attend continue meeting online. “We’re Zooming. The pastor is searching for a place,” she said. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Will Sellers: The consensus justice

It was no surprise when 60 years ago President John F. Kennedy nominated Byron White as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. With few detractors and almost nationwide acclaim, White was almost everyone’s choice, and his confirmation was dizzying. Nominated on April 3, his judiciary committee hearing began just eight days later. After White testified for 15 minutes, his nomination was unanimously approved and immediately moved to the Senate floor, where he was confirmed by a simple voice vote. On April 16 – less than two weeks after his nomination was announced – White took the oath of office. During his 31 years on the Supreme Court, Justice White did his best to remain obscure. He loathed the press, rejected all attempts at biography, and even destroyed his personal papers. He considered his 994 opinions as the best expression of his judicial philosophy. Though little-known today, White was once a household name – a sports hero whose fame and name identification rivaled anyone appointed to the court before or since. Typifying what would now be referred to as a scholar-athlete, White was a halfback at the University of Colorado, leading his team to an undefeated regular season followed by post-season play in the Cotton Bowl. Nicknamed “Whizzer White” because of his swift rushing ability, White was the runner-up for the 1937 Heisman Trophy. At the ripe age of twenty-one, he faced a critical decision. He was nominated for a Rhodes Scholarship but was also drafted by the nascent NFL Pittsburgh Pirates and offered the highest salary in the league. White considered his options and decided to do both, committing to play professional football in the fall and then head to Oxford when the season ended. Solving this personal dilemma would portend his practical way of handling cases. White’s matriculation at Oxford was cut short when World War II began in Europe. He enrolled in Yale law school and used his earnings from professional football, which he continued to play, to fund his tuition. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, White left law school and joined the navy. He served in the Pacific as an intelligence offer and was assigned to debrief a young John F. Kennedy when his PT boat sunk. At war’s end, White completed law school graduating first in his class and earning a clerkship with Chief Justice Fred Vinson. He eventually returned home to Colorado, where the economy was booming. White developed a successful law practice negotiating contracts and closing transactions for businesses and investors. His courtroom experience was limited to a handful of minor criminal cases. While never a candidate, White was active in the local Democrat Party, working on any number of campaigns and using his celebrity status as a football hero to lend credibility to the candidates he supported. One candidate, in particular, needed credibility by association. John F. Kennedy was a backbench U.S. senator from Massachusetts, and few in Colorado, much less the western United States, had any idea who he was. In searching for someone to organize his presidential campaign in the West, Kennedy’s advisors chose White. It turned out to be a brilliant decision, and as the campaign developed, White grew close to the Kennedy family, which came to rely upon him for solid, practical advice. Once Kennedy was elected, White’s raw organizational intelligence and managerial skill earned him a job in the administration. The Kennedys’ realized that White could run the Justice Department while Bobby held the title of Attorney General and worked on other matters. As Deputy Attorney General, White handled the day-to-day operations of the Justice Department, hired staff, and organized the bureaucracy to support President Kennedy’s agenda. His work gave him a very high profile, especially with members of Congress who wanted certain constituents appointed to positions within their states. And so, when a vacancy occurred on the Supreme Court, he was the president’s confidential first choice, but before White could be officially nominated, other candidates, for publicity’s sake, had to be vetted. As a result of this process, Kennedy was confronted with the opportunity to appoint the first African-American as a Supreme Court justice. During the presidential campaign, Kennedy had proactively worked to earn the support of Martin Luther King, Jr., and other prominent Black ministers throughout the South, but, in return, they demanded more than lip service to promoting civil rights and appointing minorities to office. With the first Supreme Court vacancy, Kennedy was worried that Dr. King might demand the nomination of Judge William Hastie, but King never expressed disappointment with White. While White’s nomination was well-received, a few detractors worried that his lack of courtroom experience and judicial service might prove detrimental. In addition, no one could determine if he would be a liberal or conservative jurist, and when asked to define the role of the Supreme Court, White simply replied, “to decide cases.” White became the justice liberals loved to hate, and conservatives hated to love. No doubt Kennedy supporters were disappointed in his dissenting opinions in landmark cases like Miranda and Roe. But conservatives, too, would find White’s jurisprudence hard to embrace when he approved affirmative action in higher education, agreed with campaign finance regulation, and ruled Georgia’s death penalty to be unconstitutional. When he announced his retirement, the press was elated to see him go. His decisions were viewed critically, and his career on the court seen as the one blight tarnishing the Camelot myth. The enigma of Byron White may be that in an age of celebrity judges, high stakes confirmation hearings, arguments over judicial philosophy, and national political groups funding campaigns to oppose and support a nominee, he was a judge who merely wanted to decide cases. He eschewed pontificating on various high-minded principles, did nothing to court favorable public approval, and left no record of his means or methods of reaching decisions. Much like Sir Christopher Wren’s tribute in St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, “If you seek his monument, look around you,”

Bill seeks higher fines for taking down Confederate statues

A legislative committee advanced a proposal Tuesday to increase the fines on cities that take down Confederate monuments in Alabama. The Senate Governmental Affairs Committee advanced a bill by Republican Sen. Gerald Allen of Tuscaloosa that would increase the fine for violating the Alabama Memorial Preservation Act, which prohibits the removal and renaming of monuments and memorials that have stood for at least 40 years. The bill would increase the fine from a $25,000 one-time fee to a $5,000 per day fine that would accumulate until the monument is replaced. Allen said he believed the heftier fine would serve as a deterrent. Some Alabama cities have opted to pay the current $25,000 fine as part of the cost of taking down a Confederate monument “The fine will stay there until the monument, statue, street sign — whatever it may be — is replaced,” Allen told the committee. Sen. Linda Coleman-Madison, a Democrat from Birmingham, said she believed the $5,000 daily fine was excessive, particularly for smaller cities. “You are going up and up and up and up, and now you are in the punitive stage,” Coleman-Madison said of the total fines a city could face. While the Alabama Memorial Preservation Act does not mention Confederate monuments, it was enacted as some Southern states and cities began removing monuments and emblems of the Confederacy. Birmingham and several other cities have been fined under the law for taking down Confederate monuments. Most recently, the Alabama attorney general’s office told Montgomery officials that the city faces a $25,000 fine for renaming Jeff Davis Avenue for Fred Gray, a famed civil rights attorney who represented Rosa Parks and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. The bill also calls for the Alabama Historical Commission to design, construct and place a statue of the late civil rights leader John Lewis by the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma. Lewis, a native of Alabama who became a long-serving Georgia congressman, was beaten by state troopers on the bridge in a melee known as Bloody Sunday. The committee also advanced a bill that would make it a felony offense, punishable by up to 20 years in prison, to damage a historic monument while “participating in a riot, aggravated riot, or unlawful assembly.” Both bills now move to the full Alabama Senate. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Omicron wave leaves U.S. food banks scrambling for volunteers

Food banks across the country are experiencing a critical shortage of volunteers as the omicron variant frightens people away from their usual shifts, and companies and schools that regularly supply large groups of volunteers are canceling their participation over virus fears. The end result, in many cases, has been a serious increase in spending by the food banks at a time when they are already dealing with higher food costs due to inflation and supply chain issues. “Food banks rely on volunteers. That’s how we keep the costs low,” said Shirley Schofield, CEO of the Food Bank of North Alabama. “The work still gets done but at a much higher expense.” The extent of the problem was highlighted this past week during the national holiday for Martin Luther King Jr. Day when many food banks have traditionally organized mass volunteer drives as part of a day of service. Michael Altfest, director of community engagement for the Alameda County Community Food Bank in Oakland, California, called it “without fail, our biggest volunteer event of the year.” But many food banks chose to cancel their plans this year or continued with radically lower numbers than pre-pandemic years. Altfest said his food bank’s King Day event drew 73 people spread out over two shifts when previous years had drawn more than 200 people, with all volunteer slots booked up before New Year’s Day. The food bank did not attempt an event last year. In Tallahassee, Florida, plans for a volunteer-driven event on the holiday were abruptly canceled when all the volunteers dropped out. Schofield said executives at her food bank in Huntsville, Alabama, are debating whether to cut back on their mobile food pantry distributions because they simply do not have enough volunteer-packed food boxes to hand out. The shortage of volunteers is not universal. Michael Manning of the Greater Baton Rouge Food Bank in Louisiana said his volunteer numbers have remained strong, and his MLK Day event proceeded normally with two shifts of more than 50 people. But several food banks have reported a similar dynamic: minimal volunteers for most of 2021, then a surge last fall through November and December before falling off a cliff in January. Food banks generally use volunteers to sort through donations and to pack ready-made boxes of goods for distribution. It is common practice to arrange for local companies or schools to send over large groups of volunteers, but that has left the system vulnerable to those institutions pulling out all at once. At the Second Harvest of the Big Bend food bank in Tallahassee, Florida, the volunteer numbers have remained solid through the omicron surge. But CEO Monique Van Pelt said she was forced to cancel her MLK Day plans because the volunteers all came from a single corporate partner that “didn’t think it was safe for them to gathering as a group in such tight quarters.” Jamie Sizemore had planned for 54 volunteers from three corporate groups at the Feeding America, Kentucky’s Heartland food bank in Elizabethtown, Kentucky. But two groups canceled, and the third sent less than half its promised number. “We did manage to pick up some last-minute individuals for a total of 12 volunteers for the day,” said Sizemore, the executive director. She added that a long-term contingent of eight assigned Kentucky National Guardsmen frequently help fill the volunteer gaps. Even outdoor volunteer work, with seemingly less exposure risk than warehouse work, has suffered. In Irvine, California, the Second Harvest Food Bank of Orange County has launched an ambitious farm project on 45 acres of land provided by the University of California. So far, 22 acres have been planted with cabbage and broccoli, and it’s harvest time. The plan was conceived with the intention of using up to 300 volunteers per week, organized in groups from corporate partners such as Disney. But most of the partnering organizations have suspended their volunteer drives amid the omicron surge. “It’s a bummer because it’s a great outdoor experience,” said Claudia Keller, the food bank’s CEO. “We’re crossing our fingers that this is a short-term thing. We know many of the volunteers are chomping at the bit to get out there.” The sudden absence of volunteer labor forces most food banks into more expensive choices. When the farm runs short of volunteers, paid laborers are employed. At the Capital Area Food Bank in Washington, D.C., CEO Radha Muthiah has to order truckloads of prepackaged boxes of mixed goods to distribute because there aren’t enough volunteers to pack. “When it’s prepackaged, that tends to increase the price significantly,” Muthiah said. A truckload of produce on pallets costs about $9,000, but a truckload of ready-to-distribute care packages can cost between $13,000 and $18,000, she said. In addition to the financial costs, some executives point out a more subtle impact. “Volunteerism is about more than just getting the boxes packed,” said Schofield from the Alabama food bank. “It builds camaraderie and a sense of community. It’s a sign of a healthy community at large.” Vince Hall, government relations officer for Feeding America, which coordinates the work of more than 200 food banks, said the volunteer numbers are partially a reflection of long-term emotional fatigue and burnout. As the nation endures a second pandemic winter and the omicron variant rolls back some of the progress people expected from the vaccine, long-time volunteers are wearing down. “These people who are really part of the bedrock of our volunteer workforce, They’ve been doing this since March of 2020,” Hall said. “It takes an emotional toll on people.” Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

William Haupt III: Know your rights and how to protect them

“At one time, getting passing grades in civics and U.S. history were prerequisites for high school graduation. Our biggest mistake was to adopt common core and abandon this.” – Michael Polelle Over five decades ago, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. It established standards to protect the voting rights of all qualified U.S. voters. Contrary to liberal psychosis, the Voting Rights Act applies to every voter equally. It set parameters for each state to engrain within its voting laws. To ensure equality, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed to protect the rights of ethnic minorities. But its core provisions, like the Voting Rights Act, protects the civil rights of all Americans equally. Contrary to leftist logic, neither of these gave more rights to one group and less rights to another. Five decades later, many Americans don’t know the Civil Rights Act protects all citizens from age, gender, ethnic and religious discrimination, in addition to minority groups. Government cannot give any form of preference to one group without abridging the same rights that others are entitled to. As Boomers began to feel the pinch of age prejudice, many forgot that age discrimination is a key provision in the Civil Rights Act. And very few seniors ever filed complaints with the Department of Justice about this. “We are marching for the civil rights of the Negros and those of all Americans.” – Martin Luther King Jr Even fewer Americans know why our states were obliged to update their voting laws after the last election. All states laws must comply with provisions in the Voting Rights Act to protect “all voters.” In response to the mayhem during the 2020 election, when blue states made up new laws as they went along, 43 states updated voting laws to prevent a repeat of the insane bedlam that took place in 2020. Citizens asked state lawmakers to ensure that nobody could ever question how anybody who couldn’t get elected dogcatcher in his own state get the most votes in U.S. presidential history. Since the Constitution obligates states to enforce the Voting Rights Act, after the last election, they reviewed all mail-in voting, counting ballots received after Election Day and ballot drop-boxes. All these issues truncated the intent of the Constitution and Voting Rights Acts. Yet in the woke world, if you don’t win the brass ring or can’t hijack it, you bellyache that your voting rights were violated! By law, states are responsible for updating existing election laws when they do not comply with the Voting Rights Act that protects all individual voting rights. Yet progressives and identity groups are squealing like pigs in a bacon factory? Why are they upset with states trying to protect their rights? The woke society is built on double standards. It can’t exist any other way. Wokes make up laws to justify breaking laws they don’t like. Either play the game their way, or they will take their ball away. “I learned that being ‘woke’ is being brainwashed by extremist liberal propaganda.” – Lillian Fang Until the presidential election of 2000, the merits of the Voting Rights Act were seldom questioned. But the fiasco in Florida proved, if progressives want to win badly enough, no law will ever stand in their way. After five weeks of trying to turn Al Gore into a winner, the choice of our nation’s new leader came not from the citizens, but from a 5-4 majority of U.S. Supreme Court justices. Liberal contempt for our voting rights began long before the 2000 election when blue states started moving to all mail-in voting. They had the national media’s pump primed; there was no way Al Gore could possibly lose. When the media abruptly called the election for Gore, they ended up with egg on their faces, and progressives and their liberal attorneys around the U.S. cried out election fraud! “Hi. I’m Al Gore, and I used to be the next president of the United States of America.” – Al Gore Although liberal media pollsters and pundits had been predicting a landslide victory for Al Gore, in the real world Pew Research, Gallop, and other independent groups pictured a much tighter race. They forecasted that fallout from the Clinton-Lewinsky sex scandal would mobilize conservatives against the left’s loose morality. Al Gore lost the entire south and even his home state, Tennessee. In reaction to allegations about voter fraud, hanging chads, and especially mail-in ballots that were supposedly miscounted, Democrats petitioned Washington to review U.S. voting rights again. The 2005 Commission on Election Reform, chaired by liberals Jimmy Carter and former Secretary of State James Baker, concluded that the biggest threat to voting integrity was with mail-in ballots. “We conclude that mail-in voting remains the largest source of potential voter fraud.” – Jimmy Carter Concerns about vote tampering have a long history in the U.S. They helped drive the move to the secret ballot, which all U.S. states adopted between 1888 and 1950. Secret ballots made it harder to intimidate voters and to monitor which candidate a voter had voted for. One University of Florida study found complaints about fraud fell by an average of 14% after states adopted secret ballots. In woke America, facts are an “inconvenient truth.” There have never been more complaints about denial of individual rights, violations of voting rights, and claims of “systematic racism” coming from people who don’t know the rights “they have” and “do not have” than any time in American history. “I have faith in the United States and our ability to make good decisions based on facts.” – Al Gore In 1865, following the Civil War, the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments and the 19th Amendment in 1920 guaranteed equal rights and universal suffrage for all Americans. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 protected those rights. That is why we must have voter ID laws. Every illegal vote cast nullifies the votes of the legitimate voters. Still,

Judge clears 1955 court record of civil rights pioneer, Claudette Colvin

A judge has approved a request to wipe clean the court record of a Black woman who was arrested for refusing to move to the back of a segregated Alabama bus in 1955, months before Rosa Parks gained international fame for doing the same. A judge granted the request by Claudette Colvin, now 82, in a brief court order made public Thursday by a family representative. Parks, a 42-year-old seamstress and activist with the NAACP, gained worldwide notice after refusing to give up her bus seat to a white man on Dec. 1, 1955. Her treatment led to the yearlong Montgomery Bus Boycott, which propelled the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. into the national limelight and often is considered the start of the modern civil rights movement. A 15-year-old high school student at the time, Colvin refused to shift seats on a segregated Montgomery bus even before Parks. A bus driver called police on March 2, 1955, to complain that two Black girls were sitting near two white girls in violation of segregation laws. One of the Black girls moved toward the rear when asked, a police report said, but Colvin refused and was arrested. The case was sent to juvenile court because of Colvin’s age, and records show a judge found her delinquent and placed her on probation “as a ward of the state pending good behavior.” Colvin never got official word that she had completed probation through the ensuing decades, and relatives said they assumed police would arrest her for any reason they could. At the time she asked a court in October to expunge her record, Colvin said she did not want to be considered a “juvenile delinquent” anymore. “I am an old woman now. Having my records expunged will mean something to my grandchildren and great-grandchildren. And it will mean something for other Black children,” Colvin said at the time in a sworn statement. Now that Juvenile Court Judge Calvin L. Williams has approved the request, Colvin said in a statement that she wants “us to move forward and be better.” “When I think about why I’m seeking to have my name cleared by the state, it is because I believe if that happened it would show the generation growing up now that progress is possible, and things do get better. It will inspire them to make the world better,” she said. Colvin never had any other arrests or legal scrapes, and she became a named plaintiff in the landmark lawsuit that outlawed racial segregation on Montgomery’s buses. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Montgomery faces fine, lawsuit for dropping Confederate name

Alabama’s capital city last month removed the Confederate president’s name from an avenue and renamed it after a lawyer known for his work during the civil rights movement. Now the state attorney general says the city must pay a fine or face a lawsuit for violating a state law protecting Confederate monuments and other longstanding memorials. Montgomery last month changed the name of Jeff Davis Avenue to Fred D. Gray Avenue. Gray, who grew up on that same street, represented Rosa Parks and others in cases that fought Deep South segregation practices and was dubbed by Martin Luther King Jr. as “the chief counsel for the protest movement.” The Alabama attorney general’s office sent a Nov. 5 letter to Montgomery officials saying the city must pay a $25,000 fine by Dec. 8, “otherwise, the attorney general will file suit on behalf of the state.” Montgomery Mayor Steven Reed said changing the name was the right thing to do. “It was important that we show, not only our residents here, but people from afar that this is a new Montgomery,” Reed, the city’s first Black mayor said in a telephone interview. It was Reed’s suggestion to rename the street after Gray. “We want to honor those heroes that have fought to make this union as perfect as it can be. When I see a lot of the Confederate symbols that we have in the city, it sends a message that we are focused on the lost cause as opposed to those things that bring us together under the Stars and Stripes.” The Alabama Memorial Preservation Act forbids the removal or alteration of monuments and memorials — including a memorial street or memorial building — that have stood for more than 40 years. While the law does not specifically mention memorials to the Confederacy, lawmakers approved the measure in 2017 as some cities began taking down Confederate monuments. Violations carry a $25,000 fine. Mike Lewis, a spokesman for Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall, declined to comment on the letter to the city. This is the first time the law is being used regarding a street name change, he said. The all-Republican Alabama Supreme Court in 2019 reversed a circuit judge’s ruling that declared the law an unconstitutional violation of the free speech rights of local communities. Reed said they knew this was a possibility when the city renamed the street. Donors from across the country have offered to pay the fine for the city. He said they are also considering taking the matter to court. “The other question we have to answer is: Should we pay the fine when we see it as an unjust law?” Reed said. “We’re certainly considering taking the matter to court because it takes away home rule for municipalities.” Alabama’s capital city is sometimes referred to as the “Cradle of the Confederacy” because it is where representatives of states met in 1861 to form the Confederacy, and the city served as the first Confederate capital. The city also played a key role in the civil rights movement — including the Montgomery Bus Boycott. The Montgomery County school system has voted to rename high schools named for Davis and Confederate General Robert E. Lee — although the names have not yet been changed. Several cities have just opted to take down Confederate monuments and pay the $25,000 fine. The state recently collected a $25,000 fine after suing officials in Huntsville, where the county removed a Confederate memorial outside the county courthouse last year. Marshall last year issued a video message chiding local officials that they are breaking the law with monument removals. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

TV station donates thousands of items to Alabama Archives

A television station has donated thousands of items including historic footage from the civil rights era to the Alabama Department of Archives and History, which will make the material available to the public. WSFA-TV in Montgomery announced it had given the agency materials dating to the 1950s, including footage from news conferences by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., coverage of the Freedom Riders in 1961, and original film from the “Stand in the School House Door” by then-Gov. George C. Wallace in 1963. The video also includes scenes from a visit to the NASA center in Huntsville by President John F. Kennedy and Vice President Lyndon Johnson in 1962 and special reports on the death of former University of Alabama football coach Paul “Bear” Bryant in 1983. While the TV station was planning to switch locations, managers determined it wasn’t practical to move the large numbers of delicate film reels and boxes full of video and other items. Steve Murray, the Archives director, said archivists had long suspected the WSFA studios held valuable content for historical preservation, and his department jumped at the opportunity to add to its collection when a phone call came in late 2019. “It was one of those kind of chilling moments … where the hair stands up on the back of your neck when you see these closets after closets of tapes and films,” Murray explained. “Just the opportunity to take something off the shelf and see a label … related to the civil rights movement or to other major public events and Alabama’s life and history really made you, made me appreciate the value of what was there.” The donation includes more than 7,000 audiovisual items in a variety of formats, plus WSFA-TV scrapbooks, photographs, negatives, correspondence with viewers and officials, and newsletters. “We are intimidated by this collection, to be honest with you, because it is huge,” said Meredith McDonough, digital assets director for Archives and History, “and because it is unlike anything we have.” Under the terms of the donation agreement, the department will use the material to benefit state citizens through museum exhibitions, K-12 classrooms, and other educational products. WSFA-TV will be able to broadcast and publish the content of the collection after it is digitized. The agency is processing “test batches” of film and it will take years to fully process the boxes. So far, about 15 hours of film has been digitized, which represents only 30 items in the collection. No payment was made for the collection, WSFA-TV reported. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Alabama city adds Juneteenth as holiday for its employees

An Alabama city is giving its employees an additional paid holiday after its City Council voted to recognize Juneteenth. The holiday marks June 19, 1865, when federal troops entered Galveston, Texas, some two months after the Civil War ended. The day, also known as “Freedom Day,” was established to mark the end of slavery in the country. Prattville City Council District 2 Councilman Marcus Jackson, the sole Black member on the panel, lobbied for the recognition. Ideas ranged from a city-sponsored event to a holiday, The Montgomery Advertiser reported. “It’s a good day in Prattville,” Jackson said. “I’m very appreciative that the City Council passed the resolution unanimously. Having the paid holiday is important because it marks a day when a large group of Americans learned about their freedom. It is our shared history, as Americans. “We have made great progress since then. But we still have to work on our efforts to ensure diversity and inclusivity. Having this paid holiday can help keep a spotlight on those efforts.” Juneteenth became a federal holiday this year after President Joe Biden signed an executive order. Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey followed by making it a state holiday. Ivey’s move was made just before June 19. Most local governments follow the state’s holiday schedule, which provides for 14 paid holidays for state employees. Prattville Council President Jerry Starnes sponsored the move to add Juneteenth to Prattville’s holiday list. “I think it is important to observe an important day in history,” he said. “I thought the actions making it a holiday this year were a little quick. We really didn’t have any time to prepare. The council sets the holidays when we approve the budget. So this gives us plenty of time ahead of next year.” Prattville gives employees 12 holidays a year now, including one personal day taken at the employees’ request. At one time, Prattville followed the state holiday schedule, but things have changed. About five years ago, Mayor Bill Gillespie Jr. did away with the federal holidays of Presidents’ Day and Columbus Day. In their place employees were given the Friday after Thanksgiving and Christmas Eve as holidays. Earlier, former Mayor Jim Byard Jr. ended Confederate Memorial Day and Jefferson Davis’s Birthday. He did not replace those paid days off. The only Confederate-related holiday Prattville recognizes is the combined Martin Luther King Jr./ Robert E. Lee birthdays. Other local governments also recognized Juneteenth this year, including the City of Montgomery and the Autauga County Commission, which follow the state holiday schedule. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Alabama city’s planning commission OKs renaming street

A city planning commission in Alabama’s capital city has unanimously passed a recommendation to rename one of its streets for a civil rights lawyer. The recommendation to rename Jeff Davis Avenue to Fred D. Gray Avenue was passed Thursday during a City of Montgomery Planning Commission meeting, WSFA-TV reported. Gray, a Montgomery native who grew up on the street, was one of Rosa Parks’ attorneys when she was arrested for refusing to move to a seat in the back of a public bus. He also represented Martin Luther King Jr. a number of times, and helped in the legal fight to allow African American students to learn at the University of Alabama. One business owner on Jeff Davis Avenue spoke against the recommended change said doing so will have a negative impact on him. “It’s gonna cost us about $2,500, $3,000 in time and money to contact and change stationery, invoices, contracts, contact suppliers,” said Robert Jehle, owner of Jehle Building & Tile Company. The recommendation next heads to the city council for approval. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

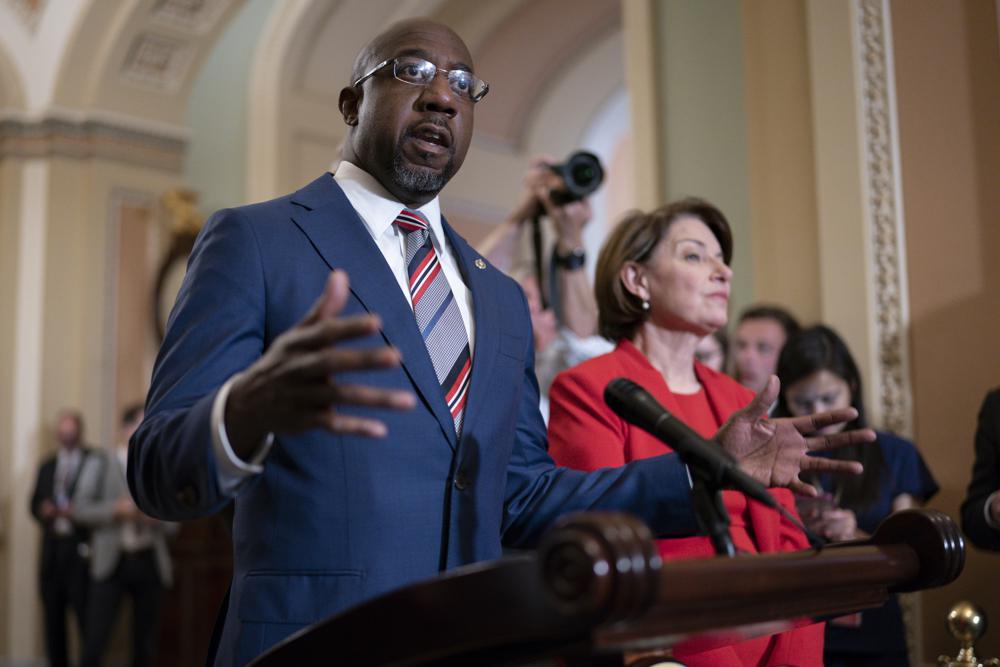

Beyond D.C. partisanship, Raphael Warnock makes broad pitch in Georgia

On Capitol Hill, Sen. Raphael Warnock assails Republicans’ push for tighter voting rules as “Jim Crow in new clothes,” while his campaign operation blasts emails bemoaning dire risks to democracy. Back home, Georgia’s first Black senator is more subtle, pitching a “comprehensive view of infrastructure” and avoiding talk of his reelection fight already looming just months after he won a January special election runoff with Senate control at stake. “I’m busy being Georgia’s United States senator,” Warnock said, smiling, as he brushed aside a question recently about famed football hero Herschel Walker potentially running for his seat as a Republican. Indeed, the preacher-turned-politician spent the Independence Day recess hopscotching from an inland port in the conservative Appalachian foothills to liberal Atlanta’s urban microbreweries and sprawling public hospital, then the suburban defense contractors in between. At each stop, he highlighted the federal money he’s routed — or is trying to route — to his state for health care, national security research, rural broadband and urban walking paths, among other projects. “We as Georgians should be proud of all that happens in the state,” Warnock said at the Georgia Tech Research Institute, cheerleading ongoing projects and arguing for more federal spending. “I had some sense of it before becoming a senator. But what I have been able to see firsthand is impressive.” The high-wire act will test whether Warnock, who will seek his first full Senate term next year, can again stitch together a diverse, philosophically splintered coalition that tilted Georgia to Democrats in 2020. He’s still the high-profile freshman whose election gave Democrats unified control in Washington, but now he’s angling to be seen as a “senator for all Georgians” delivering for the state with nuts-and-bolts legislative work. The approach is part necessity given Georgia’s toss-up status: Warnock and Sen. Jon Ossoff, also a freshman, each won their seats by less than 100,000 votes out of 4.5 million runoff ballots; Democrat Joe Biden topped Republican Donald Trump in the presidential contest by less than 13,000 votes out of 5 million last November. Warnock’s gambling that he can be an unapologetic advocate for Democrats’ agenda, including on voting laws, yet still prove to Georgians beyond the left’s base that he is a net-benefit for them. Come November 2022, that would mean maintaining enthusiasm among the diverse Democratic base in metro areas and Black voters in rural and small-town pockets, while again attracting enough suburban white voters, especially women, who’ve drifted away from Republicans in the Trump era. The senator doesn’t disclose such bald-faced election strategy. His office declined a one-on-one interview for Warnock to discuss his tenure and his argument for a full six-year term. Still, his public maneuvering illuminates a preferred reelection path. “Georgia is such an asset to our national security infrastructure,” Warnock said at the Georgia Tech outpost adjacent to Dobbins Air Reserve Base. He praised public and private sector researchers who develop technology for the Pentagon, U.S. intelligence and other agencies, saying they “keep our national defense strong and protect our service members.” He held up the installation as a beneficiary of the U.S. Innovation and Competition Act, a $250 billion package that cleared the Senate on a rare bipartisan vote, 68-32, eight more than the 60-vote filibuster threshold that’s held up Democrats’ plans on election law and infrastructure. As Warnock visited the Appalachian Regional Port, an inland container port in north Georgia, he highlighted the proposed RURAL Act, which he’s co-sponsoring with Republican Sen. Mike Braun of Indiana. It would speed upgrades of rural railway crossings. Afterward, Warnock’s office announced a $47 million grant for port expansion. The surrounding Murray County delivered 84% of its presidential vote to Trump last November. Warnock won just 18% there on Jan. 5. In Atlanta, where Warnock resides and still serves as senior pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church, which Martin Luther King Jr. once led, the senator lined up more squarely with Democrats’ priorities. Yet even then, Warnock was deliberate when discussing Republicans. “It’s ridiculous that we haven’t expanded Medicaid,” he declared outside Grady Memorial Hospital, a vast public complex in downtown Atlanta. He noted that Georgia, still run by Republicans at the state level, remains one of a dozen states not to expand eligibility under Congress’ 2010 health insurance overhaul. Warnock accused state politicians of “playing games,” though he never mentioned Gov. Brian Kemp by name. Warnock said he’d soon introduce a measure allowing citizens in non-expansion states to be covered. That aligns with one of Biden’s key presidential campaign pledges. The senator later stood along the Atlanta Beltline, an old railroad path redeveloped into a pedestrian and cycling thoroughfare around the city’s perimeter. He touted a $5 million federal investment, billing it as an example of Democrats’ wide interpretation of infrastructure, and alluding to the GOP’s narrower “hard infrastructure” definition. “America needs a home improvement plan,” Warnock said. He endorsed a pending bipartisan infrastructure deal negotiated at the Biden White House but said Democrats should use Senate rules to pass an even larger package over Republican objections in the 50-50 chamber. To be sure, even with his emphasis on infrastructure, Warnock didn’t shy away from the voting rights debate when asked. As on infrastructure, Warnock said Democrats should use Senate rules — or rewrite them, in the case of the filibuster — to counter the spate of Republican state laws tightening access to absentee and early voting. Yet in all those arguments, Warnock tried to frame his case as something beyond party. “I’m making a jobs-and-economic viability argument,” he said on Medicaid expansion. “Once you have basic health care, you can pursue employment, and with a kind of freedom that you can work knowing that you’re covered.” He added that “rural hospitals are closing” under the financial strain of treating the uninsured and underinsured. Warnock extended that analysis to rural broadband and the urban Beltline. Both, he said, connect individuals to economic opportunities around them. Housing and child care, he argued, are “basic infrastructure” for the same reasons. As for voting rights, Warnock stood beside his