Alabama only state to limit media to 1 witness at execution

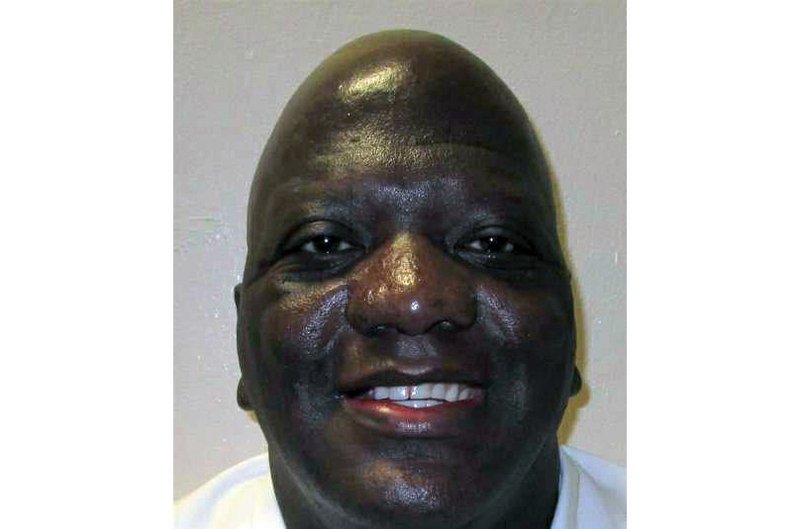

Alabama will be the third state to carry out an execution during the COVID-19 pandemic and will be the only prison system to reduce the number of news media witnesses to a single reporter. The Alabama Department of Corrections said because of COVID-19 precautions only one reporter, a representative of The Associated Press, will be allowed to witness Thursday’s lethal injection of Willie B. Smith. The state in the past allowed five media witnesses, although the number of outlets sending reporters is sometimes less than that. Only the federal government, Texas, and Missouri have carried out executions since the pandemic began last year. None reduced the number of media witnesses to a single reporter. There have been 19 executions carried out since April of 2020, according to a database maintained by the Death Penalty Information Center. All of them were attended by multiple reporters with the exception of one lethal injection in Texas where the prison system neglected to notify reporters it was time to carry out the punishment. Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, said the media serves an “irreplaceable function” as “the public’s witnesses and play a vital role in holding states accountable when executions visibly go wrong.” “If an execution is not safe enough to be witnessed by the full complement of reporters, the remedy is not to decrease accountability and increase secrecy by excluding media witnesses who would otherwise be permitted to attend. If an execution is not safe enough for witnesses, it is not safe enough to go forward at all,” Dunham wrote in an email. Paige Windsor, the executive editor of the Montgomery Advertiser, said the news organization disagreed “that the press restrictions were necessary for COVID mitigation, especially once a vaccine was available.” “We object to any laws, procedures or practices that limit press coverage of state business, particularly when that business involves killing a human being in the public’s name. Reporting on all aspects of these proceedings is how a free press ensures the public’s business is carried out as prescribed,” Windsor said in an emailed statement. The Alabama Department of Corrections did not immediately respond to an email seeking comment. The prison system wrote in a media advisory issued Monday that the number of witnesses were being limited, “due to measures necessary because of the COVID-19 pandemic.” It is the same procedure and witness restrictions the state planned to use at Smith’s original execution date in February. That execution was called off by the state. Two reporters witnessed the two executions carried out in Missouri during the pandemic. And two or more reporters witnessed the executions in Texas, with the exception of the May lethal injection of Quintin Jones. Two reporters had been set to witness the execution, but a prison spokesperson never received the usual telephone call to bring them to the execution chamber. Thirteen of the 19 executions were carried out by the federal government. The AP served as the national media pool, providing coverage to other outlets, but local news outlets also witnessed the executions. An AP analysis earlier this year found that those executions may have acted as a superspreader event for COVID-19 infections. Most states have not carried out death sentences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Smith is scheduled to be executed by lethal injection for the 1991 kidnapping and killing of Sharma Ruth Johnson, 22. Prosecutors said Smith abducted Johnson at gunpoint from an ATM in Birmingham, stole $80 from her and then took her to a cemetery where he shot her in the back of the head. Smith’s attorneys on Tuesday asked the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals to block the lethal injection, arguing the intellectually disabled inmate could not understand the prison paperwork that laid the groundwork for the planned lethal injection. Lethal injection is the main execution method used in Alabama. But after lawmakers authorized nitrogen hypoxia as an execution method in 2018, the new law gave death row inmates a 30-day window to select nitrogen hypoxia as their execution method. Nitrogen hypoxia is a proposed execution method in which an inmate would breathe only nitrogen, thus depriving him or her of oxygen, causing unconsciousness and then death. Three states have approved it as an execution method, but it has never been used. Smith did not turn in a form selecting nitrogen, paving the way for the state to execute him next week by lethal injection. The state has not developed a procedure for using nitrogen as an execution method, and at least for now is not scheduling executions with nitrogen hypoxia. “I did not understand the Election Form because I’m slow and have trouble reading,” Smith said, according to a declaration filed with the emergency request for a preliminary injunction. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Pastor can hold inmate’s hand during execution

Alabama said it will allow a death row inmate’s pastor to hold his hand during a lethal injection next month, a decision that was made to end litigation over the issue. Lawyers for Alabama wrote in a June court document that inmates can now have a personal spiritual adviser present with them in the execution chamber and the adviser will be allowed to touch them. The agreement settled litigation over Alabama inmate Willie Smith’s request to have his personal pastor with him as he is put to death. Smith was convicted of the 1991 kidnapping and murder of 22-year-old Sharma Ruth Johnson in Birmingham. According to court documents, Smith’s spiritual adviser can: anoint the inmate’s head with oil; pray with the inmate and hold his hand as the execution begins, as long as the adviser steps away before the consciousness assessment is performed; and remain in the execution chamber until the curtains to the witness rooms are drawn. The description was included in a footnote in a joint filing in June by the state and Smith’s attorneys in which the two sides announced they had reached an agreement over the spiritual adviser issue. The case is one of a series of legal fights over personal spiritual advisers at executions. A Texas death row inmate won a reprieve Wednesday evening from execution for killing a convenience store worker during a 2004 robbery after claiming the state was violating his religious freedom by not letting his pastor lay hands on him at the time of his lethal injection. Alabama officials in February called off Smith’s execution after the justices maintained an injunction issued by the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals saying he could not be executed without his pastor present in the chamber. Alabama officials wrote in a court filing that the state recognized “its policy restricting access to the execution chamber to institutional chaplains was unlikely to survive further litigation” and that it had reached an agreement to allow Smith’s pastor to be with him in the chamber. Alabama has rescheduled Smith’s execution for next month. The state wrote in court filings that it will inform other inmates of their opportunity to select a spiritual adviser to accompany them in the execution chamber. However, it noted that the pastor will not be in the chamber when the time of death is called to protect the privacy of the person who performs that function. In the past, Alabama routinely placed a Christian prison chaplain employed by the state in the execution chamber to pray with an inmate if requested. The state stopped that practice after a Muslim inmate asked to have an imam present. The prison system, which did not have a Muslim cleric on staff, maintained until recently that nonprison staff would not be allowed in the chamber. Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.

Justice is meant to be blind to all factors, including age

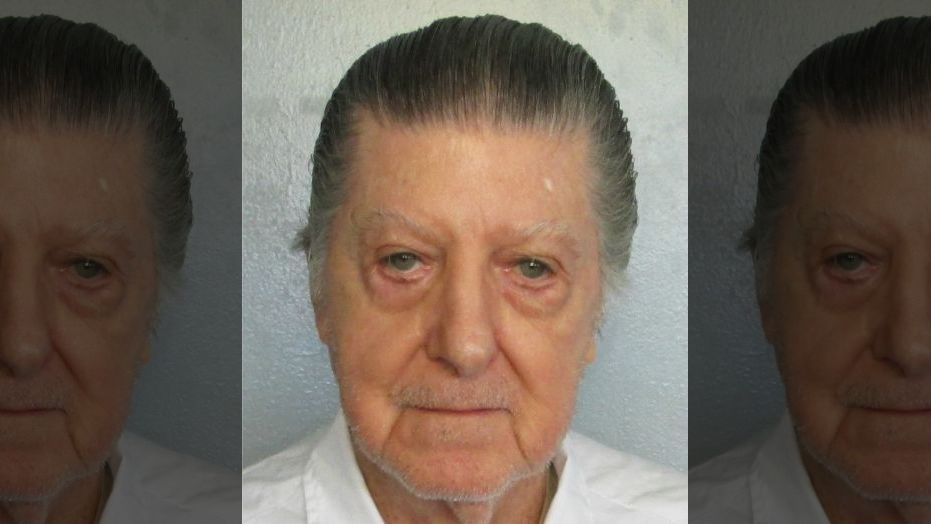

Justice is meant to be blind. She’s blind to all of the outside factors that would affect an outcome of fairness. I’ve seen a lot of people in the last week oppose the use of the death penalty for Walter Leroy Moody, 83, due to his age. They were wrong. The state was right to execute him. He was sentenced to death in 1996 for the capital murder of Judge Robert Vance. The death penalty isn’t an outcome that our justice system hands out lightly. There are far more avenues for those convicted to escape it than there were for their victims to escape their fate or their families and loved ones to escape living in the shadow of reality of that included a heinous often violent crime. There are ways to get out of the death penalty. The courts allow an appeal process that often leads to years and years of waiting to see justice served. This process should not be allowed to be an automatic get out of your sentence card if you can take up as much time as possible. The question of fairness or kindness should not fall to a system that is rendering a punishment chosen by a judge and/or jury. No magic age or magic turning point in health should mean one deserves compassion over justice. Where was compassion when the defendant committed the crimes that got them there? If anything this latest execution should serve as a motivator for justice to move more swiftly for everyone involved. If it is unfair or unjust to execute the old, than once they’ve exhausted all reasonable appeals, let the punishment be handed down without further pause. Was justice served, yes. Due process allowed this man more years than he probably should have had but it owes him no more. The court doesn’t hand down sentences based on the old man you may become in an over burdened criminal justice system. The sentence is given based on the acts of the man sitting in court. That is what is right that is what is fair. The physical treat posed by this man may not have been grave today but the threat posed by setting a precedent that you can evade justice with time is and was grave.

Jim Zeigler: Executions of murderers take too long — waaaaay too long

It now appears (8 p.m.Thursday) that the execution of Walter LeRoy Moody can go forward tonight in Alabama. He killed a federal judge over 30 years ago. Folks, 30 years is too long to carry out a sentence. Killers are not worried about what may happen 30 years from now. They think in terms of the next 30 minutes. It is very little deterrent to a would-be killer that he MIGHT be executed 30 years later. We have got to correct this problem and start carrying out swifter justice. The family of the victim has been suffering 30 years. We the taxpayers have been paying Moody’s room, board and medical expenses for 30 years. I am working on a plan that will greatly speed up executions without increasing the danger of executing the wrong person. I call the plan “Execution Delayed is Justice Denied.” When complete, I will release it and ask for your support. ••• Jim Zeigler is State Auditor of Alabama.

Alabama executes 83-year-old inmate Walter Leroy Moody

Alabama has executed the oldest U.S. inmate to be put to death in modern times, an 83-year-old man convicted of a federal judge’s mail-bomb slaying. Authorities say Walter Leroy Moody Jr. was pronounced dead at 8:42 p.m. CDT Thursday after a lethal injection. He made no final statement and did not respond when a prison official asked him if he had any last words. The non-profit Death Penalty Information Center says Moody became the oldest inmate put to death in the United States since the resumption of U.S. executions in the 1970s. Moody was convicted of killing U.S. Circuit Judge Robert S. Vance of Birmingham, who died when he opened a package mailed to his home in 1989. Prosecutors have described Moody as a meticulous planner who committed murder by mail because of his obsession with getting revenge on the legal system. He also was convicted in federal court for a bombing that killed Robert E. Robinson, a black civil rights attorney from Savannah, Georgia. Republished with permission from the Associated Press.

Donald Trump opioid plan includes death penalty for traffickers

President Donald Trump’s plan to combat opioid drug addiction calls for stiffer penalties for drug traffickers, including the death penalty where appropriate under current law, a top administration official said. It’s a fate for drug dealers that Trump has been highlighting publicly in recent weeks. Trump also wants Congress to pass legislation reducing the amount of drugs needed to trigger mandatory minimum sentences for traffickers who knowingly distribute certain illicit opioids, said Andrew Bremberg, Trump’s domestic policy director, who briefed reporters Sunday on the plan Trump is scheduled to unveil Monday in New Hampshire, a state hard-hit by the crisis and that he once referred to as “drug infested.” The president will be joined by first lady Melania Trump, who has shown an interest in the issue as it pertains to children. Trump drew criticism last year after leaked transcripts of his telephone conversation with Mexico’s president showed he had described New Hampshire as a “drug-infested den.” The Washington Post published the transcripts. Death for drug traffickers and mandatory minimum penalties for distributing certain opioids are just two elements under the part of Trump’s plan that deals with law enforcement and interdiction to break the international and domestic flow of drugs into and across the U.S. Other parts of the plan include broadening education and awareness, and expanding access to proven treatment and recovery efforts. Trump has mused openly in recent weeks about subjecting drug dealers to the “ultimate penalty.” The president told the audience at a Pennsylvania campaign rally this month that countries like Singapore have fewer issues with drug addiction because they harshly punish their dealers. He argued that a person in the U.S. can get the death penalty or life in prison for shooting one person, but that a drug dealer who potentially kills thousands can spend little or no time in jail. “The only way to solve the drug problem is through toughness,” Trump said in Moon Township. He made similar comments at a recent White House summit on opioids. “Some countries have a very, very tough penalty — the ultimate penalty. And, by the way, they have much less of a drug problem than we do,” Trump said. “So we’re going to have to be very strong on penalties.” White House officials referred questions about the death penalty and drug traffickers to the Justice Department, which said the federal death penalty is available for several limited drug-related offenses, including violations of the “drug kingpin” provisions in federal law. Doug Berman, a law professor at Ohio State University, said it was not clear that death sentences for drug dealers, even for those whose product causes multiple deaths, would be constitutional. Berman said the issue would be litigated extensively and would have to be definitively decided by the U.S. Supreme Court. Opioids, including prescription opioids, heroin and synthetic drugs such as fentanyl, killed more than 42,000 people in the U.S. in 2016, more than any year on record, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trump has declared that fighting the epidemic is a priority for the administration but critics say the effort has fallen short. Last October, Trump declared the crisis a national public health emergency, short of the national state of emergency sought by a presidential commission he put together to study the issue. “We call it the crisis next door because everyone knows someone,” said Kellyanne Conway, a Trump senior adviser. “This is no longer somebody else’s community, somebody else’s kid, somebody else’s co-worker.” Trump will also discuss how his plans for a U.S.-Mexico border wall and punishing “sanctuary” cities that refuse to cooperate with federal immigration authorities will help combat the opioid crisis, Conway told reporters traveling with the president. Other elements of the plan Trump call for a nationwide public awareness campaign, which Trump announced last October, and increased research and development through public-private partnerships between the federal National Institutes of Health and pharmaceutical companies. Bremberg said the administration also has a plan to cut the number of filled opioid prescriptions by one-third within three years. The stop in New Hampshire will be Trump’s first as president. He won the state’s 2016 Republican presidential primary but narrowly lost in the general election to Hillary Clinton. It follows a visit to the state last week by retiring Sen. Jeff Flake, R-Ariz., a persistent Trump critic. Flake told New Hampshire Republicans that someone needs to stop Trump — and it could be him if no one else steps up. Republished with permission from the Associated Press.

House approves legislation to streamline death penalty appeals

The Alabama House of Representatives on Tuesday approved a bill that would streamline the appeals process for death row inmates. SB187, the Fair Justice Act, streamlines the appeals process by requiring inmates to raise claims such as ineffective counsel at the same time as direct appeal claiming trial errors. It was approved by the House 74-26. The bill’s sponsor, Alabaster-Republican Sen. Cam Ward says the bill should drop the appeals time from roughly 18 years down to nine. However, many House Democrats argue it increases the chances the state could execute an innocent person. Attorney General Steve Marshall disagrees. He thinks the bill is the solution to the state’s inefficient appeals process. “There is no doubt that Alabama’s system for reviewing capital cases is inefficient and in need of repair,” said Marshall. “The average death row inmate appeal time is over 15 years and rising. Each year that these appeals drag on, the general public is further removed from and even desensitized to the horrendous crimes that led to the sentences of every individual on death row. But, for the families of victims, the pain is not numbed with the passing of years. The endless appeals process reopens their wounds again and again.” Marshall continued, “This legislation is about justice, and justice should be fair and swift. The Fair Justice Act takes nothing away from a death row inmate in terms of the courts reviewing his case, but streamlines the appellate process so that the direct appeal and the state post-conviction stage occur simultaneously.” The Fair Justice Act passed the Alabama Senate on April 18. It will return to the Senate for concurrence or conference committee.

Daniel Sutter: Score one for juries

Alabama is currently the only state which allows judges to impose a death sentence over the decision of the jury. This is changing, as the legislature has passed a bill ending Alabama’s death penalty judicial override. This change is consistent with the role juries have historically played in protecting individual freedom. Death penalty cases proceed in two phases. First, evidence is presented and the jury determines guilt. A guilty verdict on the death penalty eligible offense triggers the penalty phase, where the jury decides on death or life in prison. Alabama judges have been able to impose the death penalty when the jury decided on a life sentence, or a life sentence instead of death. Overrides have imposed a death sentence about ten times more often than they have spared a defendant. What is wrong with judges overriding the jury? After all, judges normally impose sentences after a conviction. Judges could well apply the death penalty more consistently. Jurors typically will only know the facts of the case they hear, and may be unaware of sentences handed down in similar cases. I see two problems with the judicial override, one related to judges’ incentives and the other related to juries’ role in limiting government. Alabama elects judges, so the judges with override power must run for reelection. In principle elections make judges (and other government officials) do what we want, but reality is more nuanced. Elections are decided by the citizens who vote, and voters are never perfectly informed. Most of us value justice and dislike crime, so we like judges who are tough on crime without violating the law. Overrides to impose the death penalty allow judges to show how tough they are on criminals. Whether an override furthers justice is a harder question. The citizens on the jury have heard all the evidence and evaluated the credibility of all the witnesses. Their informed, considered decision was for a life sentence. That a judge imposed the death penalty in a murder case will influence far more votes than the subtleties relevant to know if this sentence served justice. Judicial override undermines the jury’s protection against government overreach. The right to a trial by a jury of one’s peers emerged in England to limit the power of kings. English common law holds that the law prescribes rules people should follow to live in peace and exists prior to the establishment of government. Common law is consistent with the view that governments exist to serve citizens. America’s founders brought this common law, limited government heritage to our shores. Limited government emerged in England against a historical backdrop of absolute monarchs. The kings wanted their word to be law, while the common law regulates the affairs of free people. The kings wanted to use law to control people, while free Englishmen were only supposed to be punished for criminal actions. This created a tension. The right to trial by a jury limits the government. The king might want to jail or execute a political opponent. But before punishment can be imposed, a jury of other citizens must be convinced with evidence of a crime. The principle of double jeopardy is closely tied to trial by jury, since this prevents presenting the evidence to juries until one delivers the desired guilty verdict. Many luminaries have recognized this crucial role of juries. English jurist William Blackstone called juries “the grand bulwark of all liberty.” Thomas Jefferson saw juries “as the only anchor ever imagined by man, by which a government can be held to the principles of its constitution.” James Madison, the Father of the U.S. Constitution, thought that the jury trial was its grandest measure protecting freedom. Constitutional rules help ensure that governments serve the interests of the people. Allowing only juries to determine criminal punishment is a vital constitutional rule. The question of capital punishment deeply divides Americans. If this ultimate punishment is ever justified, we the people should have the final say, and so eliminating Alabama’s judicial death penalty override is a change for the better. ••• Daniel Sutter is the Charles G. Koch Professor of Economics with the Manuel H. Johnson Center for Political Economy at Troy University and host of Econversations on TrojanVision. The opinions expressed in this column are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of Troy University.

Alabama lawmakers to vote on death penalty bill

No capital murder sentencing procedure in the United States has been more criticized than that of Alabama’s. As the only state in the country that permits elected trial judges to override jury verdicts to give criminals the death penalty instead of a life sentence, Alabama’s judicial sentencing procedures are once again the topic of debate. On April 4, when lawmakers from the Alabama House of Representatives return from a two-week spring break, they will debate this controversial 1976 policy that has resulted in judicial overrides 107 times in the past four decades. Last month, the Alabama Senate approved a similar bill doing doing away with judicial override on a 30-1 bipartisan vote. Pike Road- Republican stateSen. Dick Brewbaker, the bill’s sponsor, clarified the bill only affects future cases and not any inmates currently on death row. He says judicial override in death penalty cases is contrary to the tradition of American justice that a jury from the community should determine both the verdict and sentence. In a recent study by the Alabama-based Equal Justice Initiative, one of the groups opposed the state’s death penalty system, found that in nearly all of those cases judges imposed death sentences. The study also revealed twenty-one percent of 199 people currently on the state’s death row were sentenced through such judicial overrides. [Photo Credit: Yolanda Martinez | The Marshall Project]

Lone lawmaker crusades against the death penalty in Alabama

Hank Sanders closed his eyes, pressed his hand to his forehead and tried to recall the first time he petitioned the state of Alabama to abolish the death penalty. Was it 2000? Or maybe 1998, shortly after the American Bar Association called for a moratorium on capital punishment? The 74-year-old senator from Selma couldn’t say for sure, so he asked his secretary to dig into the files. For nearly two decades, Sanders has introduced bills to end Alabama’s ability to take a person’s life — an unsuccessful endeavor in a state that has defied national trends away from capital punishment and still houses one of the country’s largest death row populations. Sanders is undeterred, arguing that the death penalty unfairly targets poor African-Americans. Again this year, as he has since 2000, he put forward legislation to stop executions in the Deep South state. “You don’t fight whether you’ll win or not,” Sanders said in his Montgomery statehouse office. “You fight based on whether you think your position is right.” If past years are an indication, his legislation will again die in committee. Years ago, Sanders thought he could win support for a three-year pause on executions. When that failed for 12 straight years, he began calling for a full repeal. “It’s a lonely fight,” said Sanders, a Democrat in the state Senate since 1983. An Alabama native, he grew up in a three-room house, the second of 13 children in a rural town during the racial segregation of Jim Crow. The African-American lawmaker has dedicated much of his career to civil rights. He organized voter registration drives and walked in 1965 with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in the Selma-to-Montgomery march that preceded the Voting Rights Act. The private law firm he co-founded doggedly pursued civil rights cases and won more than $1 billion for black farmers who alleged discrimination by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Sanders said opposing capital punishment is yet another attempt to bring justice to Alabama. “It’s an extension of my fight for civil rights,” he said. Alabama’s 183 death row inmates make that the fourth largest U.S. grouping of prisoners awaiting execution. More than half are black, though African-Americans make up about a quarter of the state’s population. People who study capital punishment say its more frequent application to minorities is linked to racial prejudice. “It is inseparable of historical discussion of race, slavery, lynching, Jim Crow,” said Robert Dunham, executive director of the nonprofit Death Penalty Information Center, which opposes capital punishment. Nationally, the number of yearly executions has dropped dramatically over a quarter century, partly due to difficulty securing lethal injection drugs and waning public support, according to the center. Last year, 20 inmates were put to death, the lowest figure since 1991. Annual death sentencing rates are also down nearly 90 percent since 2000. Thirty-one states still allow capital punishment, but 10 states account for about 80 percent of the country’s total death row population. California, with the largest death row population by far at 749 inmates, has executed only 13 prisoners since 1976, figures from the Death Penalty Information Center show. Alabama has used capital punishment 58 times over the same period. Sanders said the drop in executions is positive, but he holds out hope for a U.S. Supreme Court ruling outlawing the punishment. Death penalty advocates say it deters crime and is less costly than life imprisonment. Both sides bicker over conflicting studies on whether it depresses homicide rates. “At the end of the day, whether you go with Timothy McVeigh or Dylann Roof, the only way you’re going to deter people from committing those heinous acts is to have a death penalty,” said Republican state Sen. Trip Pittman. He referred to McVeigh, the Oklahoma City bomber executed in 2001, and Roof, recently sentenced to die for a South Carolina church shooting massacre. People personally affected by vicious crimes said Sanders’ attempts to repeal the only punishment that will bring them closure are doing justice a disservice. “I don’t understand why people have all this compassion for these people on death row,” said Janette Grantham, executive director of the advocacy group Victims of Crime and Leniency. Her brother, a county sheriff, was murdered in 1979 by a man later handed a life sentence. Sanders’ efforts would make sense in a perfect world, she said, but “it’s not a fantasy world to me to want fairness and justice.” Though Sanders’ crusade has never gotten far, he insists many lawmakers quietly agree capital punishment should be ended but fear losing votes: “There have been other politicians who have said to me, privately, ‘You’re right, but I can’t touch that.’” Republished with permission of The Associated Press

Bills to give juries final say in death penalty cases moving in Alabama Legislature

A pair of state lawmakers sponsoring bills to give juries the final say in death penalty cases will hold a news conference in front of the State House Tuesday. Pike Road Republican Sen. Dick Brewbacker and Tuscaloosa Democratic Rep. Chris England are both sponsoring bills that would disallow Alabama judges from overriding the jury sentencing recommendation in death penalty cases. Alabama is the last state in the country that allows judges to override a jury’s sentencing recommendation in capital cases. Current law requires 10 of 12 jurors to recommend the death penalty. The pair will be joined by Kimble Forrister, the state coordinator for advocacy group Alabama Arise, on the steps of the State House at 11:15 a.m. Tuesday to make their case for ending judicial overrides in Alabama. The news conference is part of Alabama Arise’s 2017 Legislative Day, where the group will bring in advocates from around the state to discuss death penalty reform and the group’s other legislative efforts with state lawmakers. Over the past 40 years, Alabama judges have overridden jury recommendations 107 times, more than 90 percent of the time to hand down a death sentence when a jury recommended life imprisonment. Brewbacker’s bill, SB 16, has cleared the Senate Thursday with a 30-1 vote, while England’s version, HB 32, won approval from the House Judiciary Committee earlier this month. The major difference between the two bills is that England’s version requires the jury recommendation to be unanimous, while Brewbacker’s bill leaves the 10 out of 12 threshold unchanged.

Anti-death penalty protesters arrested outside Supreme Court

A Supreme Court spokeswoman says 18 demonstrators have been arrested outside the court during a protest against the death penalty. The protest on Tuesday marked 40 years since the first person was executed after the Supreme Court allowed capital punishment to resume in 1976. The arrests took place after protesters climbed the steps of the court’s marble plaza in a steady rain to unfurl a large banner reading “Stop Executions.” Dozens of other protesters stood on the sidewalk in front of the court chanting, singing hymns and holding signs that listed the names of every person executed over the past four decades. Executions and new death sentences have been declining in recent years. Twenty people were executed last year, the fewest since 1991, when 14 people were put to death. Republished with permission of The Associated Press.